Wilmington insurrection of 1898 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wilmington massacre of 1898 |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

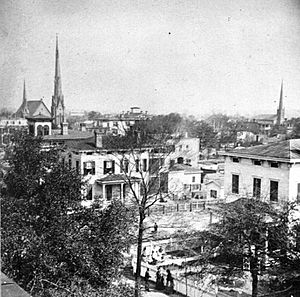

Mob posing by the ruins of The Daily Record

|

|

| Location | Wilmington, North Carolina |

| Date | November 10, 1898 |

| Target |

|

|

Attack type

|

|

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | est. 14–300 black residents killed |

| Victims |

|

| Perpetrators |

|

|

Number of participants

|

2,000 |

| Motive |

|

|

Goals of Attack: (1) Government overthrow

(2) Maintenance of Antebellum Racial Hierarchy |

|

The Wilmington insurrection of 1898, also known as the Wilmington massacre of 1898, was a violent event in Wilmington, North Carolina, on November 10, 1898. It was a coup d'état (a sudden, illegal overthrow of a government) and a massacre carried out by white supremacists. White newspapers first called it a "race riot" caused by Black people. However, later studies have shown it was a planned attack by white supremacists to remove a legally elected government. This is the only known event of its kind in United States history.

A group of white Southern Democrats planned and led a mob of 2,000 white men. They overthrew Wilmington's elected local government, which was made up of both Black and white leaders. They forced Black and white political leaders to leave the city. They also destroyed Black-owned businesses and property, including the city's only Black newspaper. Between 60 and over 300 people were killed.

The Wilmington coup changed politics in North Carolina after the Reconstruction Era. It led to stricter racial segregation and made it harder for African Americans to vote across the South. Historians say this event showed that "white supremacy" was more important than the legal rights and equal protection Black Americans were promised by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Contents

How It Started

Before the American Civil War in 1860, most people in Wilmington were Black. It was also North Carolina's largest city, with nearly 10,000 residents. Many enslaved and free Black people worked at the city's port, in homes, and as skilled workers.

After the war, formerly enslaved people, called freedmen, moved to towns and cities. They sought work and safety in Black communities away from white control. Tensions grew in Wilmington because of a lack of supplies. Confederate money was worthless, and the South was very poor after the long war.

In 1868, North Carolina accepted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This meant Reconstruction policies were recognized. The state government was led by Republican officials, including white and Black people. Freedmen were eager to vote and strongly supported the Republican Party, which had freed them and given them citizenship. However, conservative white Democrats disliked these changes. They felt Black residents, Unionist "carpetbaggers," and "scalawags" (white Southerners who supported Reconstruction) were behind them.

Some Confederate veterans were also angry because they couldn't vote or hold office for a time. Many white Democrats were still bitter about losing the war. Some joined the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). This group used violence to stop Black people from organizing and voting.

Democrats took back control of the state government in 1870. After the KKK was stopped by the federal government, new paramilitary groups formed in the South. By 1874, groups called Red Shirts appeared in North Carolina. They were like a military arm of the Democratic Party.

Democrats wanted to change how local governments worked. They wanted state officials to appoint local leaders instead of people electing them. They changed the state constitution to gain more control. These changes included reducing the number of judges and putting local governments under state control. They also made public schools separate for Black and white children. Democrats became known as supporters of white Americans.

In 1876, Zebulon B. Vance, a former Confederate soldier, ran for governor. He used harsh, racist language against the Republican Party. Through Vance, Democrats hoped to gain more power in the eastern part of the state.

However, in that region, poor white farmers were often angry at big banks and railroad companies. These companies charged high fees and used economic policies that hurt the poor South. These farmers joined with Black Republicans who faced similar problems. In 1892, during an economic downturn, they formed an alliance called the Fusion coalition. They supported self-governance, free public education, and equal voting rights for Black men.

Wilmington's Growth

In the late 1800s, Wilmington was still North Carolina's largest city. About 55% of its 25,000 people were Black. Many Black professionals and business owners lived there, and a Black middle class was growing.

The Republican Party in Wilmington included both Black and white members. Unlike many other places, Black people were elected to local offices. They also held important community positions. For example, three of the city's aldermen were Black. Black people also worked as police officers, mail carriers, and in other civic roles.

African Americans also had a lot of economic power. Many formerly enslaved people used their skills in the marketplace. They became bakers, grocers, and other skilled workers. By 1889, Black people moved into higher-paying jobs. They made up over 30% of Wilmington's skilled workers like mechanics and carpenters. They owned most of the city's restaurants and barber shops. Two brothers, Alexander and Frank Manly, owned the Wilmington Daily Record. This was one of the few Black newspapers in the state and possibly the only Black daily newspaper in the country.

Some Black people held very important business and leadership roles. Frederick C. Sadgwar was an architect and financier. Thomas C. Miller was a real estate agent and the only pawnbroker in the city. In 1897, John C. Dancy was appointed as the U.S. customs collector at the Port of Wilmington. White newspapers often used racist terms to insult him. Black professionals supported each other. Most Black professionals were clergy or teachers, jobs where they could compete fairly.

White Resentment

As Black people gained social, economic, and political power, racial tensions grew. Former slaves and their children had no inherited wealth. Many Black residents lost their savings when the Freedman's Savings Bank closed in 1874. This made them distrust banks. They also faced high interest rates on loans, nearly 15%, compared to under 7.5% for poor whites. Lenders often refused installment payments, which led to Black-owned property being taken through forced sales. This made it hard for Black people to save money or own property.

Even though Black people were nearly 60% of the county's population, only 8% owned property. They paid less than $400,000 of the nearly $6 million in property taxes. The average wealth for whites was about $550, but for Black people, it was less than $30.

Wealthy whites felt they paid too much in taxes compared to Black residents. Poor, unskilled whites also competed with Black people for jobs. They found their services were less needed than skilled Black labor. Black people were seen as progressing both too fast and too slow by white residents.

Sometimes, the homes and businesses of successful African Americans were burned by whites. But because Black residents had enough economic and political power, things were generally peaceful.

Fusionist Power

In the elections of 1894 and 1896, the Republican-Populist Fusion ticket won every statewide office. This included the governorship in 1896, won by Daniel L. Russell. The Fusionists started changing the Democrats' political system. They changed appointed local offices back to elected ones. They also encouraged Black citizens to vote.

By 1898, Wilmington's political power was held by "The Big Four" of the Fusion ticket. These included Mayor Dr. Silas P. Wright, Sheriff George Zadoc French, Postmaster W. H. Chadbourn, and businessman Flaviel W. Fosters. They worked with a group of about 2,000 Black voters and 150 whites called "the Ring." This group included prominent businessmen and influential Black families. The Ring used political support and their newspapers, the Wilmington Post and The Daily Record, to gain power.

This shift in power worried white Democrats. They challenged the new laws in court but lost. Defeated in elections and court, Democrats became aware of disagreements within the Fusion alliance. They hoped to win the 1898 elections by focusing on certain issues.

Key Issues

The Fusion coalition focused on economic issues like:

- Free Coinage: This was about whether the U.S. currency should be based on both silver and gold, or just gold. Many poor people supported using silver, calling it "the poor man's money." Fusionists wanted to increase silver coinage.

- Railroad Debt: The state had a lot of debt from expanding the Western North Carolina Railroad. Democrats blamed Republicans for this problem. Fusionists saw railroads as a symbol of capitalist greed by Democrats.

- Debt Relief: Many North Carolinians were in debt. Black people saw debt as another form of slavery and tried to avoid it. They faced very high interest rates. Fusionists wanted to lower interest rates to 6% to help both poor whites and Black people. They passed this measure in 1895.

1898 White Supremacy Campaign

In late 1897, nine important Wilmington men were unhappy with what they called "Black people's rule." They were upset about Fusion government changes that affected their businesses. Interest rates were lowered, and tax laws were adjusted, which hurt wealthy property owners. Railroad rules were also made stricter. Many Wilmington Democrats felt these changes targeted them.

These men, known as the "Secret Nine," included Hugh MacRae and others. They started planning to take back control of the government.

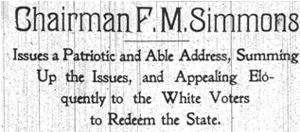

Around the same time, the new Democratic State Party Chairman, Furnifold Simmons, needed a plan for the 1898 elections. He knew that stirring up racial anger could unite white voters.

Simmons decided to build his campaign around white supremacy. He worked with the Secret Nine, who offered their connections and money. He planned to recruit "Writers" (for propaganda), "Speakers" (for powerful speeches), and "Riders" (for intimidation). He also promised large companies that Democrats would not raise their taxes if they won.

In March 1898, Simmons met with Josephus "Jody" Daniels, editor of the News & Observer, and Charles Aycock. They planned the Democratic campaign strategy.

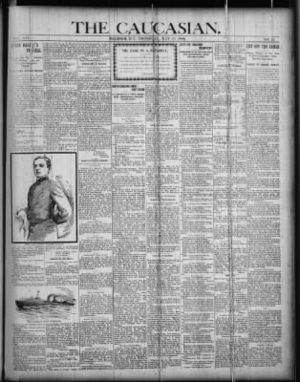

Simmons recruited newspapers that supported white supremacy, like The Caucasian. These papers called Black people "insolent" and accused them of disrespecting whites. They also claimed Black men were interested in white women and that white Fusionists supported this "domination."

On November 20, 1897, the first statewide call for white unity was issued. It urged whites to unite and "re-establish Anglo-Saxon rule and honest government." It called Republican and Populist rule "anarchy" and "evil."

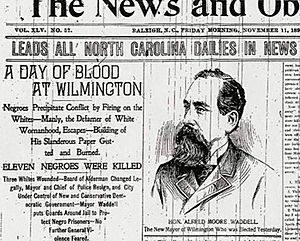

Alfred M. Waddell's Role

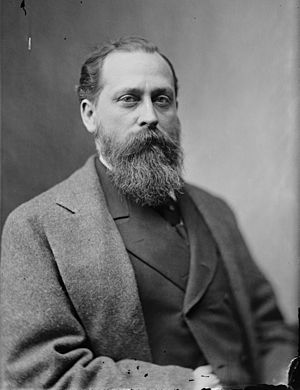

Simmons created a group of speakers to spread the message. One key speaker was Alfred Moore Waddell, an older, skilled speaker and former Congressman.

Waddell presented himself as a voice for oppressed whites. He was known as "the silver tongued orator." In 1898, Waddell was unemployed and facing money problems. He saw the White Supremacy Campaign as a chance to regain importance.

Waddell joined the Democrats' campaign to "redeem North Carolina" from Black "domination." He was "hired to attend elections and see that men voted correctly." With help from Daniels, who spread racist cartoons, Waddell and other speakers urged white men to join their cause.

White Supremacy Clubs

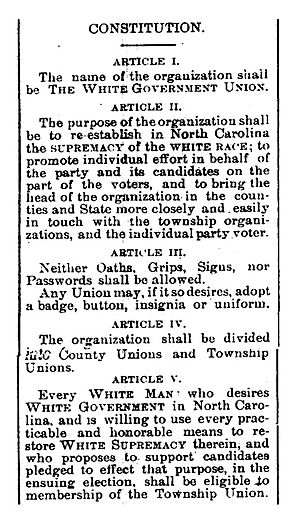

In the fall of 1898, prominent Democrats formed white supremacy clubs called the White Government Union. They demanded that every white man in Wilmington join.

One Wilmington Alderman, Benjamin F. Keith, said, "Many good people were marched from their homes ... taken to headquarters, and told to sign. Those that did not were notified that they must leave the city."

These clubs spread across the state. A "White Laborer's Union" was also formed to oppose Black people competing for jobs. This union was supported by the Wilmington Chamber of Commerce.

The white supremacists' efforts grew stronger in August 1898. Alexander Manly, editor of Wilmington's Black newspaper, The Daily Record, wrote an editorial. He responded to a speech that supported lynchings by talking about relationships between white women and Black men. Manly was the grandson of a former governor and his enslaved woman. White people were furious. Democrats, now calling themselves "The White Man's Party," used Manly's words as "proof" of bold Black people.

Reactions to the Editorial

Within 48 hours, white supremacists and newspapers across the South used Manly's words. They twisted them to fuel their cause.

Before this, The Daily Record was seen as a good Black newspaper. It had both Black and white readers and advertisers. But after the editorial, white advertisers left, hurting its income. Manly's landlord evicted him. For his safety, Manly had to move his printing press in the middle of the night. Black pastors asked their church members to buy subscriptions to help Manly's newspaper. Many Black women agreed, seeing it as the only paper that stood up for their rights.

John C. Dancy later called Manly's editorial "the determining factor" of the riot.

Rallying Support

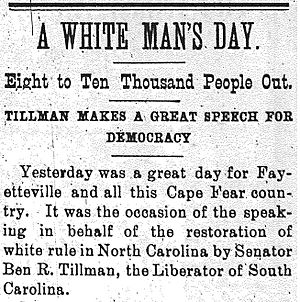

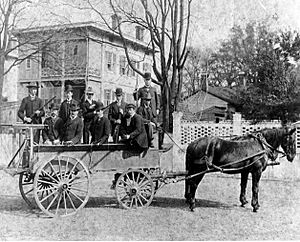

On October 20, 1898, Democrats held their biggest rally in Fayetteville. The Red Shirts appeared in North Carolina for the first time. Three hundred of them marched with 22 young white women. Cannons were fired, and a band played. A special guest was South Carolina Senator Ben Tillman, who supported violence against Black people.

Four days later, 50 important white men, including Robert Glenn and Charles Aycock, gathered at the Thalian Hall opera house. Alfred Waddell gave a speech, saying white supremacy was the most important issue for white men. Parts of his speech were printed and sent across the state.

"White Supremacy Convention"

After the Thalian Hall speech, on October 28, special trains took Waddell and other white men to Goldsboro for a "White Supremacy Convention." About 8,000 people came to hear Waddell, Simmons, Charles Aycock, and others.

Waddell ended his speech by saying white men would get rid of Black people and their white allies. He even said they would fill the Cape Fear River with enough dead Black bodies to block it.

Intimidation Tactics

Waddell's speech inspired the crowd. The Red Shirts immediately began terrorizing Black citizens and their white allies in eastern North Carolina. They destroyed property, attacked people with guns, and kidnapped people from their homes to whip them. Their goal was to scare Republican supporters so much that they wouldn't vote or even register.

Democrats put more pressure on Republican and Populist candidates. This made candidates too afraid to speak in Wilmington.

The Red Shirts were seen as "ruffians" by Wilmington's white elite. However, they were used to hold marches and rallies around the city. Mike Dowling, an unemployed Irishman, organized these events.

On November 1, 1898, Dowling led a parade of 1,000 armed men on horseback. They rode for ten miles through Black neighborhoods in Wilmington. White women waved flags as they passed. The procession ended at the Democratic Party headquarters.

The next day, Dowling led a "White Man's Rally." Every "able-bodied" white man was armed. They marched through Black neighborhoods, firing into homes and a school. The parade ended at Hilton Park, where 1,000 people greeted them with a picnic. Several defiant speakers followed.

Leading up to the election, these gatherings happened daily. White newspapers announced the times and places. At night, the rallies became like carnivals. Groups also disrupted Black churches and patrolled the streets as "White Citizens Patrols." They wore white handkerchiefs on their arms and intimidated Black citizens.

Fear and Suppression

The city's atmosphere made Black people anxious and tense. It made white people hysterical and paranoid.

Black men tried to buy guns and powder, which was legal. But white gun merchants refused to sell to them. The only weapons Black people had were a few old muskets or pistols.

Newspapers spread rumors that Black people were buying guns and planning a fight. Whites suspected Black leaders were meeting in churches.

Henry L. West, a political director for The Washington Post, came to Wilmington to cover the White Supremacy Campaign. Democrats hired detectives, including one Black detective, to investigate the rumors. The detectives found that Black residents "were doing practically nothing." To prevent any Black organizing, Democrats banned Black people from gathering anywhere.

Before the election, the Red Shirts were told to ensure Democrats won "by any means necessary." The Red Shirts had created so much fear that Black people were "in a state of terror."

1898 Election

Most Black people and many Republicans did not vote in the November 8 election. They hoped to avoid violence. Red Shirts blocked roads and drove away potential Black voters with gunfire.

Governor Russell tried to calm the situation in his hometown of Wilmington. But when his train arrived, Red Shirts surrounded his car and tried to lynch him.

Democrats won 6,000 votes, a large increase from two years prior. Later, it was found that this suggested a lot of election fraud. Mike Dowling testified that Democrats worked with the Red Shirts. They told them where to put Republican ballots so they could be replaced with Democratic votes. The Washington Post political director wrote that the Democratic victory was "largely the result of the suppression."

However, Wilmington's biracial Fusionist government remained in power. The mayor and aldermen were not up for reelection in 1898.

The night after the election, Democrats ordered white men to patrol the streets, expecting Black people to fight back.

The White Declaration of Independence

The "Secret Nine" had given Alfred Waddell's "Committee of Twenty-Five" the task of carrying out a document they wrote. This document called for taking away voting rights from Black people and overthrowing the elected government. It was called "The White Declaration of Independence."

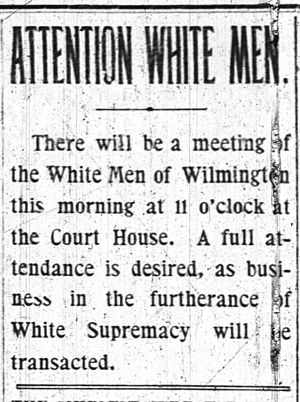

On election day, Hugh MacRae (from the Secret Nine) had the Wilmington Messenger call for a large meeting. That evening, the paper published "Attention White Men," telling all white men to meet at the courthouse the next morning for "important" business.

On the morning of November 9, 600 men packed the courthouse. Hugh MacRae and other important white Democrats were there. When Alfred Waddell arrived, MacRae gave him "The White Declaration of Independence." Waddell read it to the crowd, saying it "asserted the supremacy of the white man."

The crowd gave Waddell a standing ovation. Four hundred fifty-seven men signed the proclamation, which would be published in newspapers.

The group decided to give the city's Black residents 12 hours to agree. Alexander Manly had already closed his newspaper and left town. A white friend warned him that the Red Shirts planned to lynch him that night. Manly's friend gave him money and a password to get past white guards on Fulton Bridge. Manly and three other light-skinned Black men escaped through the woods and passed the guards.

Waddell's Committee of Twenty-Five called the Committee of Colored Citizens (CCC), a group of 32 important Black citizens, to the courthouse. They told the CCC their demands. They instructed them to tell the city's Black citizens to obey. When the Black men asked to talk and said they couldn't control Manly, Waddell said, "the time had passed for words."

Lawyer Armond Scott wrote a letter and was told to deliver it to Waddell's home by 7:30 a.m. the next day, November 10. Scott was scared and left the letter in Waddell's mailbox. Scott later claimed the letter Waddell published was not the one he wrote. He said his letter stated that Manly had stopped publishing The Daily Record two weeks before the election, removing the "alleged basis of conflict."

Massacre and Coup

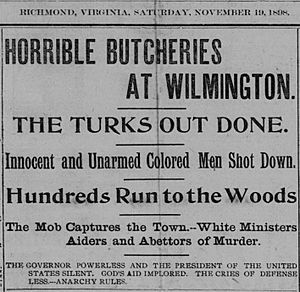

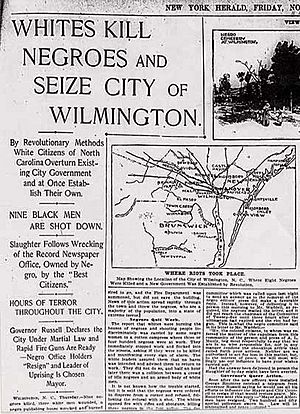

Alfred Waddell and the Committee of Twenty-Five claimed they did not receive a response from the Committee of Colored Citizens by 7:30 a.m. on November 10. About 45 minutes later, Waddell gathered about 500 white businessmen and veterans at Wilmington's armory. They armed themselves with rifles and a Gatling gun. Waddell then led the group to the office of The Daily Record, the city's Black-owned newspaper. They broke in, vandalized the building, and set it on fire. At the same time, Black newspapers across the state were also destroyed. Black people and white Republicans were also blocked from entering city centers.

After the fire, the mob of white vigilantes grew to about 2,000 men. A rumor spread that some Black people had fired on a small group of white men. White men then went into Black neighborhoods, destroying businesses and property and attacking Black residents.

As Waddell led a group to remove the elected government, the white mob rioted. Armed with shotguns, the mob attacked Black people throughout Wilmington, especially in Brooklyn, the main Black neighborhood.

Small groups of armed white men spread across the city until nightfall. Walker Taylor was authorized by Governor Russell to command the Wilmington Light Infantry troops and federal Naval Reserves. They went into Brooklyn to stop the "riot." They intimidated crowds with weapons, shooting and killing several Black men. Hundreds of Black people fled to nearby swamps for safety.

As the violence spread, Waddell led a group to the Republican mayor, Silas P. Wright. Waddell forced Mayor Wright, the aldermen, and the police chief to resign at gunpoint. The mob then installed a new city council, which elected Waddell as mayor by 4 p.m. that day.

Once Waddell was mayor, the "Secret Nine" gave him a list of important Republicans to banish from the city. The next morning, Waddell, with the Wilmington Light Infantry, marched six prominent Black people out of Wilmington. The other Black people on the list had already fled. Waddell put them on a train headed north, with armed guards to take them across the state line. Waddell then gathered the white people on the list and paraded them in front of a large crowd.

Aftermath

Wilmington's Changes

The number of Black people killed by the mob on November 10 is not certain. Estimates range from 14 to over 300. Another 20 to 50 Black people were forced to leave town.

While African Americans sought help from the federal government, many also blamed Manly for causing the attacks. John C. Dancy said in a New York Times interview that Manly was responsible. He claimed relations between Black and white people were "most cordial" before Manly's editorials. Even the National Afro-American Council called for a day of fasting for African Americans to confess "our own sins," without blaming white supremacists.

More than 2,000 Black people, including Alex and Frank G. Manly, permanently left Wilmington. They were forced to leave their businesses and properties. This greatly reduced the city's Black professionals and skilled workers. It changed Wilmington from a Black-majority city to a white-majority one. While some whites were hurt, no whites were reported killed. The city's appeals to President William McKinley for help received no response. The White House said it needed a request from the governor, but Governor Russell did not ask for help. Waddell and his team were re-elected in March 1899. Waddell remained mayor until 1905.

| Name | Role | What Happened After |

|---|---|---|

| Charles Aycock | Organizer | Became the 50th Governor of North Carolina. He defended the mob violence as necessary to keep peace. Statues in his honor are on Capitol Hill and at the North Carolina State Capitol. |

| Josephus Daniels | News & Observer Editor | Appointed Secretary of the Navy by President Woodrow Wilson during World War I. He became a close friend of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who later appointed Daniels as Ambassador to Mexico. A statue of him was removed in 2020. |

| Mike Dowling/Red Shirts | Red Shirts Leader | Awarded a special police officer and firefighter position. He later testified about how the coup was organized. |

| Rebecca Felton | Lynching Supporter | Became the first woman to serve in the United States Senate, though only for one day. She supported women's right to vote and equal pay for equal work. |

| Hugh MacRae | One of "The Secret Nine" | Donated land for a "whites only" park near Wilmington, which was named after him. The park's name was changed to Long Leaf Park in 2020. |

| Furnifold Simmons | Campaign Manager | Became a U.S. senator and held his seat for 30 years. |

| Ben Tillman | Orator | U.S. senator for nearly 25 years. He often made fun of Black people in the Senate and boasted about killing them in South Carolina. |

| Alfred Waddell | Orator; Coup Leader | Remained Mayor of Wilmington until 1905. He wrote his memoirs in 1907. |

State Politics Changes

Once in the state legislature in 1899, Democrats, who had won nearly 53% of the vote, decided to:

- Stop Black people from voting.

- Create a racial hierarchy where poor whites felt superior to Black people.

Taking Away Voting Rights

To keep "good government by the White Man's Party," the "Secret Nine" had George Rountree in the state legislature. His job was to ensure Black people couldn't vote and to stop white Republicans from working with Black people again. On January 6, 1899, Francis Winston introduced a bill to stop Black people from voting. Rountree led a committee to create a voting amendment that would get around the U.S. Constitution, which gave Black people the right to vote.

The legislature passed a law requiring new voters to pay a poll tax. They also passed a state constitutional amendment. This amendment required voters to show they could read and write any part of the Constitution. These practices hurt poor whites and over 50,000 Black men. However, to protect poor whites, Rountree added a "Grandfather clause." This clause allowed people to vote without the literacy test if they, or a direct ancestor, could vote before January 1, 1867. This rule effectively stopped almost all Black men from voting.

The clause stayed in effect until 1915, when the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional.

Start of "Jim Crow"

After the coup, Democrats began passing the state's first racial hierarchy laws. These laws made it illegal for Black and white people to sit together on trains, steamboats, or in courtrooms. They even required separate Bibles for Black and white people. Almost every part of public life was separated for poor whites and Black people.

These laws, a direct result of the brief alliance between Black people and poor whites, encouraged whites to see Black people as outsiders. They also rewarded whites for doing so, socially and psychologically. This led to more physical separation. Before the attack, Black and white people in Wilmington lived close together. But over the next years, segregation increased across the state. Whites saw improved home value, social status, and quality of life the further they lived from Black people. This reduced political democracy and strengthened the power of the descendants of former slave owners.

Until 1908, Democrats in other Southern states followed North Carolina's example. They passed laws to stop Black people from voting or made constitutional changes. They also passed laws forcing racial segregation in public places. The US Supreme Court at the time supported these measures.

1900 Election Impact

Two years after the coup, Democrats again campaigned on the idea of Black "domination." The disenfranchisement of Black people was on the ballot. Gubernatorial candidate Charles Aycock, one of the campaign's speakers, used what happened in Wilmington as a warning. He said that taking away voting rights would keep the peace. In Wilmington, only 26 people voted against Black disenfranchisement. This showed the political effect of the coup.

| Year | Republican Vote | Democrat Vote | Populist Vote | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1896 | 154,025 | 145,286 | 30,943 | 330,254 |

| 1900 | 126,296 | 186,650 | 0 | 312,946 |

| 1904 | 79,505 | 128,761 | 0 | 208,266 |

How History Was Told

"Race Riot" Narrative

On November 26, 1898, Collier's Weekly published an article by Waddell about the government overthrow. The article, "The Story of The Wilmington, North Carolina, Race Riots," was one of the first times the term "race riot" was used.

Even though Waddell had threatened to "choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses," and white mob members posed for photos in front of the burned newspaper office, Waddell described himself as a reluctant, non-violent leader. He said he was "called upon" to lead under "intolerable conditions." He painted the white mob as peaceful citizens who just wanted to restore order.

Although people of both races pointed to Democrat-backed violence as the cause, the national story largely presented Black men as the attackers. This made the coup seem justified as a response to "Black aggression." For example, The Atlanta Constitution newspaper said the violence was a reasonable defense of white honor and a necessary response against "criminal blacks."

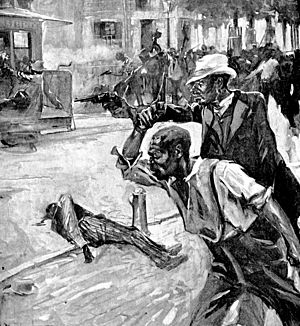

Waddell's story ignored the complex reasons for the coup. It presented the overthrow as something that "spontaneously happened," not a planned conspiracy. This helped establish the idea of the Solid South. Along with Hugh Ditzler's drawing showing Black people as armed attackers, Waddell and Ditzler effectively defined "race riot" and set a standard for how it was used.

The North Carolina Legislature used this term in 2000 when it set up the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission. It is still used by the State Archives of North Carolina and the State Library of North Carolina in its online NCPedia.

"Massacre" vs. "Insurrection"

Waddell's account in Harper's Weekly presented the violence and coup as a "noble" event. It compared it to the American Revolution. Many whites saw the coup's leaders as "revolutionary" heroes who led an "insurrection" against a "riotous" Black threat. After the coup, those involved began to change the language used to describe the events.

However, Black survivors and the community insisted the event was a "massacre."

Some people who try to change history deny that white people were responsible. They blame Black people or say the white actions were noble. They argue that white people were not bad, but honorable people fighting for "law and order." By not admitting that white people used crime and violence to achieve "law and order," they keep their ancestors' values affirmed.

The event was called a "riot," "insurrection," or "conflict" for a long time. This was because Black survivors' stories were ignored. The Daily Record was destroyed, so there were no Black media accounts. Also, the South adopted the "Lost Cause" idea. This idea made white violence during the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow seem like acts of justice.

The "Lost Cause" narrative helped the North and South reunite emotionally. It brought sentimentality and celebrations that allowed Southern whites to feel regional pride and American identity. However, historians say this reunion was "exclusively a white man's phenomenon." Black Americans were sacrificed for this reunion.

A Gatling gun and an armed mob fired on people who couldn't arm themselves. The different names for this event ("massacre" vs. "riot") caused arguments about how to tell its history and deal with its effects.

1998 Centennial Commission

By the early 1990s, different groups in Wilmington had different understandings of the events. This led to interest in discussing and remembering the coup. This followed efforts to recognize similar events where white mobs destroyed Black communities, like in Rosewood and Tulsa.

In 1995, informal talks began among the African-American community, UNC-Wilmington faculty, and civil rights activists. They wanted to educate residents about what truly happened and agree on a monument. On November 10, 1996, Wilmington held a program to plan for the 1998 Centennial Commemoration. Over 200 people attended. Some descendants of the 1898 white supremacy leaders were against any commemoration.

In early 1998, Wilmington planned "Wilmington in Black and White" lectures. These brought in political leaders, scholars, and activists. George Rountree III, whose grandfather was a leader of the 1898 violence, attended a discussion. He spoke of his support for racial equality but refused to apologize for his grandfather's actions, saying "the man was the product of his times." Other descendants also said they owed no apologies.

Many listeners disagreed with Rountree. Some said that even though he wasn't responsible, he had benefited from the events. Kenneth Davis, an African American, spoke of his own grandfather's achievements that Rountree's grandfather had "snuffed out."

1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission

In 2000, the state legislature recognized that the Black community had suffered greatly after the coup. This was due to state disenfranchisement and Jim Crow laws. They created the 13-member, biracial, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission. Its goal was to create a historical record and assess the economic impact on Black people.

The Commission studied the event for nearly six years. They heard from many sources and scholars. The Commission produced a long report, finding that the violence was "part of a statewide effort to put white supremacist Democrats in office and stop the political advances of black citizens." Harper Peterson, a former mayor and commission member, said, "Essentially, it crippled a segment of our population that hasn't recovered in 107 years." According to the report's author, LeRae Umfleet, "'massacre,' rather than 'riot,' does apply. That's a big, strong word, but that's what it was."

The commission made broad recommendations for reparations from the government and businesses. These would benefit Black descendants and the entire community. The Commission suggested 10 bills to the North Carolina Legislature for economic development, scholarships, and other programs. The Legislature did not pass any of them.

Historians noted that the Raleigh News & Observer had contributed to the events by publishing inflammatory stories. This encouraged white men from other parts of the state to travel to Wilmington and take part in the attacks. The Commission asked the newspapers to offer scholarships to minority students and help distribute copies of the report. They also asked that New Hanover County, which includes Wilmington, be placed under federal supervision through the Voting Rights Act. This would ensure fair voter registration and voting.

Commemorations

Several events have taken place to remember the Wilmington events:

- In 1936, Harry Hayden wrote a pamphlet that called the event a "Revolution" that saved North Carolina. In 1951, Helen G. Edmonds wrote that "the Democrats effected a coup d'etat." Her view was often overlooked at the time.

- In November 2006, the News and Observer newspaper admitted its role in spreading propaganda during the coup.

- In January 2007, the North Carolina Democratic Party officially acknowledged and apologized for the actions of its leaders during the Wilmington insurrection.

- In April 2007, a bill called the "1898 Wilmington Riot Reconciliation Act" was introduced. It would allow victims' families to sue the city for losses. The bill did not pass.

- In August 2007, the state senate passed a resolution expressing "profound regret" for the event.

- In 2007, some people pushed for the coup to be taught in school. Historians also wanted to build a memorial in Wilmington.

- In January 2017, two Wilmington writers worked with middle school students to find and copy pages of The Daily Record. They found eight pages, and seven are readable. These pages will be available online.

- In January 2018, a historical marker was approved to commemorate the event. It was installed in March 2018 on Market Street, where the rioting began.

In Media

- Charles W. Chesnutt's novel, The Marrow of Tradition (1901), described a fictional riot based on Wilmington. It showed the white violence and damage to the Black community.

- Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novel, The Leopard's Spots (1902), detailed the 1898 white supremacy campaign and massacre.

- Wilmington author Philip Gerard wrote a novel, Cape Fear Rising (1994), about the events leading to the burning of the Daily Record.

- John Sayles included the Wilmington Insurrection in his novel, A Moment in the Sun (2011).

- David Bryant Fulton, writing as Jack Thorne, wrote the novel Hanover; or, The Persecution of the Lowly. A Story of the Wilmington Massacre (2009).

- Barbara Wright's young adult novel, Crow (2012), tells the story through a fictional young African-American boy.

- A documentary film, Wilmington on Fire, was released in 2016.

- David Zucchino won a Pulitzer Prize for his book Wilmington's Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (2020).

- The Criminal podcast discussed the Wilmington insurrection in a 2021 episode.

- The BBC World Service discussed the Wilmington Insurrection in a 2022 episode.

See also

- January 6 United States Capitol attack

- Attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election

- Business Plot

- Cary's Rebellion

- Colfax Massacre

- Domestic terrorism in the United States

- Election Riot of 1874

- Jaybird–Woodpecker War

- List of attacks on legislatures

- List of coups and coup attempts by country#United States

- List of expulsions of African Americans

- Red Summer (1919)

- White backlash

Images for kids

-

Rebecca L. Felton, who gave an August 11, 1898 speech supporting lynching (image c. 1910)

-

Alexander Manly, who as editor of The Wilmington Daily Record wrote a rebuttal editorial on August 18, 1898 (image c.1880s)

-

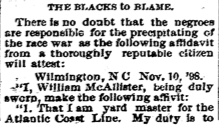

Reprint of Alexander Manly's August 18, 1898 Daily Record rebuttal editorial defending interracial relationships. Manly's editorial was used as a pretext for the insurrection in November.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |