Business Plot facts for kids

The Business Plot (also known as the Wall Street Putsch) was an alleged secret plan in 1933 in the United States. Some people believed it was a plot to overthrow the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and put a dictator in charge. A famous retired Marine Corps officer, Smedley Butler, claimed that rich businessmen wanted to create a special group of war veterans. They supposedly wanted Butler to lead this group and use it to take over the government.

In 1934, Butler gave sworn testimony to a special committee in the U.S. House of Representatives. This committee, called the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, investigated his claims. Even though no one was charged with a crime, the committee's final report said that "there is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution."

At first, many major news outlets, like The New York Times, called the plot a "gigantic hoax." But when the committee's final report came out, the Times reported that the committee believed General Butler's story was "alarmingly true." The people Butler accused of being involved all denied that any such plot existed. Most historians today agree that some kind of "wild scheme" was discussed, even if a coup was not very close to happening.

Contents

Background of the Plot

Smedley Butler and Veterans

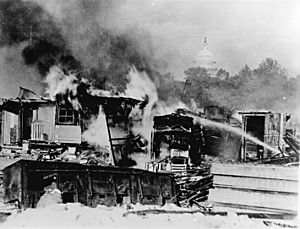

In 1932, thousands of World War I veterans gathered in Washington, D.C.. They set up camps and demanded that the government pay them bonuses they were owed. This group was called the "Bonus Army." Retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler, a very popular military figure, visited and supported them.

A few days after Butler arrived, President Herbert Hoover ordered the veterans to be removed. U.S. Army troops, led by General Douglas MacArthur, destroyed their camps.

Butler, who usually supported the Republican Party, then backed Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 election. By 1933, Butler began to speak out against big banks and capitalism. He even said he had been a "high-class muscle man" for Wall Street and big business for 33 years, calling himself a "racketeer for Capitalism."

Concerns About President Roosevelt

Many conservative businessmen were worried when Roosevelt became president. His promise to create jobs for everyone seemed to scare some business owners. They feared his plans might lead to "socialism" or too much government spending.

Some writers also say that concerns about the "gold standard" were involved. The gold standard meant that the value of money was directly linked to gold. When Roosevelt ended this, some wealthy people worried that money would lose its value. They saw Roosevelt as someone who wanted to destroy private businesses by weakening the gold backing of wealth to help the poor.

McCormack–Dickstein Committee Investigation

The McCormack–Dickstein Committee started looking into the alleged plot on November 20, 1934. They released a statement about their findings a few days later. On February 15, 1935, the committee gave its final report to the House of Representatives.

During the hearings, Butler testified that a man named Gerald C. MacGuire tried to get him to lead a coup. Butler said MacGuire promised him an army of 500,000 men to march on Washington, D.C., with financial support. Butler claimed the plan was to say the president was too sick to lead.

Even though Butler supported Roosevelt and criticized capitalism, he said the plotters believed his good reputation would help them gain public support. They thought he would be easier to control than others. Butler stated that if the coup succeeded, he would have almost complete power as "Secretary of General Affairs," while Roosevelt would become a figurehead (a leader in name only).

Everyone Butler accused denied being involved. MacGuire was the only person Butler named who testified before the committee. Other people Butler mentioned were not called to testify. The committee said there was "no evidence" to call them, as their names were only mentioned as "hearsay" (something heard from others, not directly witnessed).

On the last day of the committee hearings, January 29, 1935, a journalist named John L. Spivak published an article. It revealed parts of the testimony that had been kept secret. Spivak suggested that the plot was part of a plan by powerful financiers like J.P. Morgan, Jr. to work with fascist groups and overthrow Roosevelt.

MacGuire died on March 25, 1935, at age 37. His doctor said the accusations against him had weakened him, leading to his death from pneumonia.

Butler's Detailed Testimony

Meetings in 1933

On July 1, 1933, Butler first met Gerald C. MacGuire and Bill Doyle. MacGuire was a bond salesman for a Wall Street firm and a member of the American Legion. Doyle was a commander in the American Legion. Butler said they asked him to run for National Commander of the American Legion.

A few days later, Butler had a second meeting with MacGuire and Doyle. He stated they offered to get many supporters at the American Legion convention to ask him to speak. MacGuire left a speech for Butler to read. This speech suggested the American Legion should demand the U.S. return to the gold standard. This would ensure that veterans' bonuses would not be "worthless paper." This demand made Butler even more suspicious.

Around August 1, MacGuire visited Butler alone. Butler said MacGuire told him that Grayson Murphy's company had helped start the American Legion in New York. Butler told MacGuire that the American Legion was "nothing but a strikebreaking outfit." Butler never saw Doyle again after this.

On September 24, MacGuire visited Butler in Newark, New Jersey. Later in September, Butler met Robert Sterling Clark. Clark was an art collector and heir to the Singer Corporation fortune. MacGuire knew Clark from when Clark was a soldier in China.

Meetings in 1934

In the first half of 1934, MacGuire traveled to Europe and sent postcards to Butler. On March 6, MacGuire wrote to Clark about a French nationalist group called the Croix-de-Feu.

On August 22, Butler met MacGuire at a hotel. This was their last meeting. Butler said that MacGuire asked him to lead a new veterans' organization and try to overthrow the President.

On September 13, Paul Comly French, a reporter who had worked for Butler, met MacGuire. In late September, Butler told the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) commander, James E. Van Zandt, that co-conspirators would meet him at an upcoming VFW convention.

The committee began examining evidence on November 20. French broke the story in newspapers on November 21. On November 22, The New York Times wrote its first article about the story, calling it a "gigantic hoax."

Committee Reports

The Congressional committee's first report said: "This committee has had no evidence before it that would in the slightest degree warrant calling before it such men... The committee will not take cognizance of names brought into the testimony which constitute mere hearsay."

The final report from the congressional committee on February 15, 1935, stated: "In the last few weeks of the committee's official life it received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country. No evidence was presented... to show a connection between this effort and any fascist activity of any European country. There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient."

The report also mentioned: "This committee received evidence from Maj. Gen Smedley D. Butler... He testified before the committee as to conversations with one Gerald C. MacGuire in which the latter is alleged to have suggested the formation of a fascist army under the leadership of General Butler."

It added that MacGuire denied these claims under oath. However, the committee "was able to verify all the pertinent statements made by General Butler, with the exception of the direct statement suggesting the creation of the organization." This was supported by MacGuire's letters to Robert Sterling Clark while MacGuire was studying fascist veteran groups in Europe.

How People Reacted at the Time

On November 21, 1934, The New York Times published an article titled, "Gen. Butler Bares 'Fascist Plot' To Seize Government by Force." It reported that Butler claimed a bond salesman, representing a Wall Street group, asked him to lead an army of 500,000. Those named in the story strongly denied it.

A New York Times editorial on November 22, 1934, called Butler's story "a gigantic hoax."

Time magazine reported on December 3, 1934, that the committee "alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington... was actually contemplated."

Thomas W. Lamont of J.P. Morgan & Co. called the plot "perfect moonshine." General Douglas MacArthur, who was supposedly a backup leader if Butler refused, called it "the best laugh story of the year."

By February 16, 1935, after the committee's final report, The New York Times changed its view. It reported on its front page that the "Plan for March On Capital Is Held Proved." It stated that "definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington... was actually contemplated."

Separately, VFW commander James E. Van Zandt told the press that General Butler had warned him. Butler said he had been approached by "agents of Wall Street" to lead a fascist dictatorship in the United States. This would be disguised as a "Veterans Organization."

Later Views on the Plot

Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. said in 1958 that "Most people agreed with Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York in dismissing it as a 'cocktail putsch'." Schlesinger concluded that "No doubt, MacGuire did have some wild scheme in mind." However, he felt the country was not in much danger.

Historian Robert F. Burk wrote that the accusations likely involved some real attempts by financiers to influence veteran groups. He also noted Butler's own accusations against those he disagreed with.

Historian Hans Schmidt noted that even if Butler was telling the truth, MacGuire's true motives are unclear. He might have been playing both sides. Schmidt suggested MacGuire seemed like an "inconsequential trickster" during the hearings. If he was working for others, they were smart enough to keep their distance.

See also

In Spanish: Business Plot para niños

In Spanish: Business Plot para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |