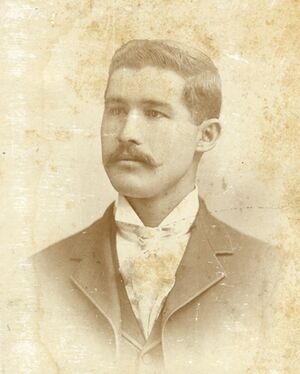

Alexander Manly facts for kids

Alexander Lightfoot Manly (born May 13, 1866 – died October 5, 1944), often called Alex, was an important newspaper owner and editor. He lived in Wilmington, North Carolina. With his brother, Frank G. Manly, he owned the Daily Record. This was the only daily African-American newspaper in North Carolina. It might have been the only black-owned daily newspaper in the entire country.

At that time, Wilmington was the largest city in North Carolina. It had about 10,000 people. Most of its residents were black, and a strong black middle class was growing.

In August 1898, Manly wrote a powerful article. He spoke out against unfair ideas that black men were dangerous to white women. He had responded to a speech by Rebecca Latimer Felton from Georgia. She had talked about black men and white women.

At this time, white politicians called Democrats were trying to stir up racial anger. They wanted to regain power in the state government. They had lost control in 1894 and 1896. This was because of a group called "fusion" candidates. These candidates were supported by both Republicans and Populists. In 1896, they even elected a Republican governor, Daniel Lindsay Russell.

When fusion candidates won elections in Wilmington, a secret group of Democrats took over the city government. This event is known as the Wilmington insurrection of 1898. It was the only time in U.S. history that a city government was overthrown by force. The Manly brothers were forced to leave town. A large angry crowd destroyed their newspaper office. This mob also attacked black neighborhoods. Many people were killed, and much of what black citizens had built was destroyed.

The Manly brothers were among 2,100 black people who left Wilmington for good after this event. Because of this, Wilmington became a city with mostly white residents. The brothers first moved to Washington, D.C. They got help from former Congressman George Henry White. He had moved there after North Carolina made new laws in 1899. These laws made it very hard for black people to vote.

Alex Manly married Caroline Sadgwar. They moved to Philadelphia and started a family. Alex Manly worked as a painter to support them. But he stayed active in politics. He helped start The Armstrong Association, which later became the National Urban League. He was also part of an African-American newspaper group.

Contents

Early Life

Alexander Lightfoot Manly, known as "Alex," was born in 1866. His birthplace was Raleigh, North Carolina. Both of his parents had mixed backgrounds. His father was a freedman, meaning he had been enslaved but was now free. He had both African and European family. His mother was a free woman of color. She also had mixed European and African family.

Through his father's side, Manly was related to Governor Charles Manly. His father's mother, Corinne Manly, had been enslaved by the Governor. Alex had brothers, Frank G. and a much younger brother named Thomas.

Alex Manly went to local schools. Then he attended Hampton University in Virginia. This was a historically black college. Later, he moved to Wilmington. There, he taught Sunday school at Chestnut Street Presbyterian Church.

Professional Career

In 1895, Manly became the owner and editor of the Wilmington Daily Record. This was the only daily African-American newspaper in North Carolina. It might have been the only one in the entire country. He owned it with his brother Frank G. Manly.

This newspaper was very forward-thinking. It was for black people in Wilmington. It was even called "The Only Negro Daily in the World." The Daily Record spoke up for black civil rights. It also pushed for better healthcare, roads, and bicycle paths. White businesses even advertised in the paper because it was so successful. The newspaper and its editors were well-respected in Wilmington.

Political Background

Wilmington had more black residents than white ones at the time. Across North Carolina, most members of the Republican Party were black. In 1894 and 1896, the state had three main political groups. These were the Republicans, the Populists, and the Democrats.

The Republicans and Populists joined together as "fusion" candidates. They won control of the state government in 1894 and 1896. They defeated the Democrats. In 1896, Daniel Lindsay Russell, a Republican, became governor. He was the first Republican governor since the Reconstruction period after the Civil War. In 1898, the fusion government passed a new law. It made it easier for more people to vote by lowering property requirements. This helped both white and black voters.

However, the Democrats worked hard to get back control of the state government. In 1897, they started talking about racial mixing to get votes. In 1898, they continued to create fear among white people. They campaigned for white supremacy. They said that white citizens should "overthrow political domination and control of the Negro."

1897-1898 Editorials

Mrs. Rebecca Latimer Felton from Georgia gave a speech. She spoke in favor of lynching black men. She said this was to "protect" white women. A local newspaper, the Wilmington Messenger, published her speech.

Manly responded on August 18, 1898, in his Daily Record newspaper. He said that white men were being unfair. They claimed to protect white women but did not care about the safety of black women. He pointed out that white men had often taken advantage of black women. This happened during slavery and after the Civil War. White men often had more power over black women in the segregated society.

Manly caused a big stir by talking about relationships between black men and white women. He said it was unfair to assume all such relationships were forced. He suggested that some white women and black men chose to be together. He also mentioned that many "black" men actually had white fathers. This showed that white men were also involved in mixed-race relationships. He argued that the idea of the "Big Burly Black Brute" was wrong. He said many black men were "attractive enough for white girls of culture and refinement to fall in love with them."

Manly wrote: "If the papers and speakers of the other race would condemn the commission of the crime because it is crime and not try to make it appear that the Negroes were the only criminals, they would find their strongest allies in the intelligent Negroes themselves; and together the whites and blacks would root the evil out of both races... Tell your men that it is no worse for a black man to be intimate with a white woman than for the white man to be intimate with a colored woman. You set yourselves down as a lot of carping hypocrites in fact you cry aloud for the virtue of your women while you seek to destroy the morality of ours. Don’t ever think that your women will remain pure while you are debauching ours. You sow the seed — the harvest will come in due time."

Racial Tensions

Manly's article was printed again in white newspapers. These included the Wilmington News and The News and Observer in Raleigh. It also got attention across the country. This was a time when racial tensions were already very high in North Carolina. Democrats were making these tensions worse to win the upcoming election.

Democrats were pushing the idea of white supremacy. They were also making people afraid of mixed-race relationships. Manly's comments about relationships between different races were very controversial. Most white people knew that white men often had relationships with black women. Some even had second families with their mixed-race children. Thomas Clawson, a white businessman and editor, said Manly's article made Wilmington "seethe with uncontrollable indignation, bitterness, and rage." Critics said Manly's article was harmful to white women.

Political Tensions

Democrats used Manly's article to their advantage. They claimed that "as long as fusion remains, Negro men would continue preying on white women." Clawson printed Manly's article every day in his newspaper before the November 9th election. Other newspapers also printed it many times. Democrats even carried copies of Manly's article to stir up anger in conversations. The article became so controversial that some Republicans claimed Democrats had written it themselves.

Democrats successfully won back control of the state government in the election on November 9, 1898. Many people across the state were watching the election results from Wilmington. This was the largest city and had a majority-black population. A secret group of white Democrats, led by Alfred Moore Waddell, had already planned the Wilmington insurrection of 1898. They planned to take over the city government if they lost the local elections.

In 1898, a mixed-race "fusion" group won the mayor's office and control of the city council. The mayor and two-thirds of the council members were white. The Democrats then started their violent takeover.

Wilmington Insurrection

Democrats were determined to overthrow the city government after losing the election. A group of white supremacists, called the Committee of Twenty-five, first decided to force Manly out of Wilmington. They had also identified many black leaders they wanted to remove from the city, including the Manly brothers. The Committee gave black community leaders a warning: the Manly brothers had to be gone by 10 A.M. on November 10. If not, they would be removed by force.

On the night of November 9, a group went to the Daily Record to find Manly. They had declared him an outlaw, meaning he could be killed on sight. The brothers fled town that night. By November 10, the brothers had left the city. A large white mob of over 1500 people destroyed the printing press. They burned the Daily Record offices to the ground. Then, they went on to attack many black citizens in what is now known as the Wilmington 1898 Coup d'etat and Massacre.

Manly found safety with George Henry White, a black U.S. Congressman from North Carolina. For a time, Manly worked in White's office. He helped write civil rights laws, but White could not get them passed in Congress.

Personal Life and Later Career

Manly and his brother Frank moved to Washington, D.C. in 1900. Frank Manly later moved to Alabama. There, he taught at Tuskegee University, another well-known historically black college.

While in Washington, Alex Manly married his fiancée, Caroline Sadgwar. She was a graduate of Fisk University and a member of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Caroline was the daughter of Frederick Cutlar Sadgwar, a respected black businessman in Wilmington. Her mother was Cherokee. Caroline and Alex were married at the home of Congressman George Henry White. White had moved to Washington, D.C., for good. This was after North Carolina passed a law in 1899 that made it very hard for most black people to vote. White had said he would not run for office again under such unfair conditions. He then became a successful lawyer and banker in Washington.

The Manlys moved from Washington, D.C., to Philadelphia. They had two sons there: Milo and Lewin. Milo became an activist. He fought for black property rights in Wilmington. He later became the head of the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission.

In Philadelphia, Alex Manly joined an African-American newspaper council. He helped start The Armstrong Association, which was a step towards creating the National Urban League. He was sad about losing his newspaper. He worked as a painter to support his family.

His sons also felt the impact of their family's losses. Manly's descendants have said the family often talked about "what might have been." They wondered what would have happened if Alex Manly had not been forced out of Wilmington and lost his newspaper. But Manly and his family kept going. They were known as "among Philadelphia's most industrious and civic minded citizens."

Lewin Manly was not as successful as his brother. He did not finish college and worked as a waiter in Savannah, Georgia. He married but later divorced. However, his son, Lewin Manly Jr., became a successful dentist. When a group was formed to study the Wilmington insurrection of 1898, Lewin Manly Jr. was among those who wanted money paid to the families of victims for their lost property and businesses.

Legacy

- In 1994, a historical marker was placed at the site of Manly's newspaper, the Daily Record. It tells about him and the 1898 event. This event is seen as a major turning point in North Carolina's history.

- A small collection of Manly's papers is kept at East Carolina University. It includes photos of him, his brother, his wife, and his son Milo.

- Manly is also discussed in a book called The North Carolina Election of 1898. This book is part of the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

|

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |