George Henry White facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

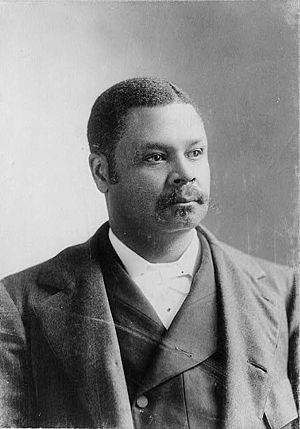

George Henry White

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from North Carolina's 2nd district |

|

| In office March 4, 1897 – March 3, 1901 |

|

| Preceded by | Frederick A. Woodard |

| Succeeded by | Claude Kitchin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 18, 1852 Rosindale, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | December 28, 1918 (aged 66) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

George Henry White (December 18, 1852 – December 28, 1918) was an American lawyer and politician. He was elected as a Republican to the U.S. Congress from North Carolina's 2nd congressional district from 1897 to 1901.

After his time in Congress, he became a banker in Philadelphia and helped start Whitesboro, New Jersey, a community for African Americans. George White was the last African American to serve in Congress at the start of the Jim Crow era. This was a time when laws in the Southern United States treated Black people unfairly. He was the only African American in Congress during his four years there.

In North Carolina, two political groups, the Populists and the Republicans, worked together. This "fusion politics" helped Republicans and African Americans win elections from 1894 to 1900. White was elected to Congress for two terms after serving in his state's government.

However, the state government, mostly controlled by Democrats, passed a new rule. This rule made it very hard for Black people to vote. Because of this, White decided not to run for a third term. He moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked as a lawyer and banker. Later, in 1906, he moved to Philadelphia.

After White left Congress, no other African American served in Congress until 1929. No African American was elected from a former Confederate state until Barbara Jordan in 1972. And it wasn't until Eva Clayton in 1992 that another African American was elected to Congress from North Carolina.

Contents

Growing Up and Learning

White was born in 1852 in Rosindale, Bladen County, North Carolina. His mother might have been a slave. His father, Wiley Franklin White, was a free person of color. This meant he was a Black person who was not enslaved. Wiley White had both African and Scots-Irish family roots. He worked in a turpentine camp, which was a place where pine trees were used to make a liquid called turpentine.

George had an older brother named John. Their father might have bought their freedom from slavery. In 1857, George's father married Mary Anna Spaulding. She was a young local woman of mixed race. Her grandfather, Benjamin Spaulding, had been freed from slavery by his own father, who was a white plantation owner. Benjamin Spaulding worked hard and bought over 2,300 acres of land, which he shared with his large family.

In 1860, the White family lived on a farm in Columbus County. George was very young when Mary Anna joined the family, so he always thought of her as his mother. She and his father had more children together, who were George's half-siblings.

George White likely first went to a small, local school paid for by families. After the American Civil War, during the Reconstruction era, North Carolina started the first public schools for Black children. In 1870, White met a teacher named David P. Allen, who encouraged him. Allen moved to Lumberton and started the Whitin Normal School. White studied there for a few years, learning subjects like Latin. He lived with Allen's family and saved money by working on his father's farm for a year. His father, Wiley White, moved to Washington, D.C., in 1872 and worked for nearly 20 years at the Treasury Department.

In 1874, White began studying at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Howard University was founded in 1867 as a historically black college, open to all races. He studied subjects to become a schoolteacher. He also worked for five months at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. This big event brought visitors from all over the world. He saw Philadelphia's active Black community, some of whom had been free since the American Revolutionary War.

White finished at Howard in 1877 and went back to North Carolina. He became a principal at a school in New Bern. He also studied law by working with a former judge, William J. Clarke. Clarke had become a Republican after the war and started a newspaper. In 1879, White passed his exams and became a lawyer in North Carolina.

Family Life

On February 27, 1879, George White married Fannie B. Randolph. She passed away in September 1880, soon after their daughter Della was born. In 1882, he married Nancy J. Scott, who also died that same year.

On March 15, 1887, he married Cora Lena Cherry. Her sister, Louisa, was married to Henry P. Cheatham, who would later become a political rival. White and Cora had three children: Mary Adelyne (called "Mamie"), Beatrice Odessa (who died young), and George Henry White, Jr.

Three of White's four children lived to be adults. Della died in 1916 in Washington, D.C. George Jr. died in Pittsburgh in 1927. Mamie died in New York City in 1974.

His wife, Cora Lena White, passed away in 1905. In 1915, George White married Ellen Avant Macdonald of North Carolina, who lived longer than he did.

A Career in Politics

In 1880, White ran as a Republican candidate from New Bern. He was elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives for one term. He helped pass a law to create four state schools for African Americans to train more teachers. In 1881, he became the principal of one of these schools in New Bern. He helped the school grow and encouraged students to become teachers.

In 1884, White returned to politics. He won an election to the North Carolina Senate from Craven County. In 1886, he was elected as a prosecutor for North Carolina's second legal district. He held this job for eight years until 1894. White had thought about running for Congress earlier, but he let his brother-in-law, Henry P. Cheatham, run instead. Cheatham was elected to the U.S. House in 1890.

White was a representative at the 1896 and 1900 Republican meetings. In 1896, he was elected to the U.S. Congress. He represented the Second District, which had mostly Black residents. He lived in Tarboro at the time. He won against the white Democratic politician, Frederick A. Woodard. The Republican president, William McKinley, helped many Republicans win that year. White also benefited because another candidate took votes away from Woodard. Also, in 1894, the state government had removed some laws that made it hard for Black people to vote. In 1896, 85 percent of Black voters participated.

In 1898, White was re-elected in a race with three candidates. During this time, it was becoming harder for Black people to vote in the South. White was the last of five African Americans who served in Congress during the Jim Crow era of the late 1800s. Two were from South Carolina, Cheatham was from North Carolina before him, and one was from Virginia. After them, no African Americans were elected from the South until 1972. This was after new federal laws in 1965 helped protect voting and civil rights for all citizens. No African Americans were elected to Congress from North Carolina again until 1992.

Since the 1880s, Republicans had been asking the federal government to watch over elections. They wanted to stop unfair practices in the South. In 1890, Representative Henry Cabot Lodge and Senator George Frisbie Hoar led a new effort. Lodge introduced a bill to make sure the 15th Amendment was followed. This amendment gives citizens the right to vote. Henry P. Cheatham was the only Black Congressman at the time. He did not speak while the House discussed the bill. It barely passed the House in July but did not pass in the Senate. Southern Democrats stopped it with long speeches.

During his time in Congress, White worked for the civil rights of African Americans. He always spoke about fairness and connected discussions on money, foreign policy, and colonization to how Black people were treated in the South. He supported a plan to reduce the number of representatives states had in Congress. This was based on the 14th Amendment, which said that if states unfairly stopped people from voting, their representation should be lowered. He challenged the House in 1899 and again after the 1900 census to pass this law.

Representative Edgar Dean Crumpacker of Indiana, who was on the committee for the census, introduced a similar plan. But it was too late for action in 1899. In 1901, he introduced another plan. His bill suggested punishing Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina. These states had passed new rules that stopped Black people from voting. (Other Southern states followed until 1908.) He suggested reducing representation based on how many people in a state could not read. He believed that people who could not read would fail the reading or education tests used to stop Black people from voting. His plan was discussed a lot, but his bill was put aside. Another effort to reduce representation in 1902 also failed.

White used his power as a Congressman to appoint several African Americans as postmasters in his district. He did this with help from North Carolina's Republican senator, Jeter C. Pritchard. They were able to hire people they supported, just like other postmasters.

After the Wilmington coup of 1898 in North Carolina, White and other representatives from the National Afro-American Council met with President McKinley. They tried to get him to speak out against lynching, which was the illegal killing of people, often Black people, by angry mobs. But they were not successful. On January 20, 1900, White introduced the first bill in Congress to make lynching a federal crime. This meant it would be handled by federal courts. The bill did not pass. Southern white Democrats, who formed a strong group called the Solid South, opposed it.

A month later, while the House was discussing expanding the country's power overseas, White again defended his bill. He gave examples of crimes in the South. He said that conditions in the region made people "provoke questions about ... national and international policy." He asked:

Should not a nation be fair to all her citizens, protect them equally in all their rights, everywhere in her land, and show herself able to govern everyone within her borders before she tries to rule over people from other countries—with different ideas and habits not like our American system of government? Or, to be clearer, shouldn't we fix problems at home first?

In 1899, North Carolina Democrats passed a new rule for the state's government. This rule made it very hard for Black people to vote. Because of this, White decided not to run for a third term in the 1900 elections. He told the Chicago Tribune, "I cannot live in North Carolina and be a man and be treated as a man." He announced he would leave his home state and start a law practice in Washington, D.C., when his term ended. White also said that constant attacks on him in newspapers had made his wife sick.

I am certain the excitement of another campaign would kill her...My wife is a refined and educated woman, and she has suffered terribly because of the attacks on me.

White gave his last speech in the House on January 29, 1901:

This is perhaps the Negroes' temporary farewell to the American Congress, but let me say, Phoenix-like he will rise up some day and come again. These parting words are in behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised and bleeding, but God-fearing people; faithful, industrious, loyal, rising people – full of potential force.

On March 4, 1901, when White's term officially ended, white politicians in Raleigh celebrated. North Carolina Democrat A. D. Watts announced:

George H. White, the rude negro... has retired from office forever. And from this hour on no negro will again disgrace the old State in the council of chambers of the nation. For these mercies, thank God."

Watts later became the first state Department of Revenue Secretary in 1921.

Life After Congress

After White left, no other African American served in Congress until Oscar Stanton De Priest was elected from Illinois in 1928. No African American from North Carolina was elected to Congress until Eva Clayton and Mel Watt won seats in 1992. White went back to practicing law and became involved in banking. He had moved his family to Washington, D.C., in 1900. White was quite wealthy, with about $30,000 in 1902.

In 1906, the White family moved to Philadelphia. This city had a well-established African American community that was growing a lot because of the Great Migration. During this time, White worked as a lawyer and started a commercial savings bank. White also helped create the town of Whitesboro in southern New Jersey. It was planned as a community for African Americans. He worked with important people like Booker T. Washington, who was the head of Tuskegee Institute, and the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. He also worked with two daughters of Judge Mifflin W. Gibbs: Ida Gibbs Hunt and Harriet Gibbs Marshall.

White was an early leader in the National Afro-American Council. This was a nationwide civil rights organization started in 1898. He served several terms as one of nine national vice presidents. He tried twice to become the Council's president but was not successful. After the Council ended in 1908, he became an early member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was founded that same year. The NAACP started a Philadelphia chapter in 1913.

In 1912, White tried to get the Republican nomination for Congress from Pennsylvania's 1st congressional district but did not win. In 1916, he became the first African American from Pennsylvania to be chosen as an alternate delegate for the Republican National Convention. In 1917, White was appointed as an assistant city lawyer for Philadelphia after Harry W. Bass passed away.

White died at his home in Philadelphia in 1918. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Eden Cemetery in nearby Collingdale. His son George, Jr. (who died in Pittsburgh in 1927) and daughter Mamie (who died in New York City in 1974) were buried next to him. His widow, Ellen White, moved to Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1920. By 1930, she married Edward W. Coston there.

Honoring His Legacy

- In 2002, the town of Tarboro, where White lived during his time in Congress, started "George White Day." They have celebrated it every year since.

- On September 26, 2009, President Barack Obama mentioned White's farewell speech in his remarks at an awards dinner in Washington, D.C.

- In 2010, a historical marker honoring White was placed on a North Carolina state highway in Tarboro.

- In 2012, a documentary called George Henry White: American Phoenix was released. It tells the story of his life and what he left behind.

- The George Henry White Fund was created to help educate people about his life and achievements.

- In 2013, a historical marker honoring White was placed in Whitesboro by a local group.

- In 2014, the George Henry White Pioneer Award was created. It is given every two years to honor his work. The first award went to Dr. Benjamin R. Justesen, who wrote the first full book about White's life and collected his writings and speeches.

- On October 29, 2015, a gravestone for White was placed at Historic Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.

- In 2015, the George Henry White Memorial Community Center was founded in Bladen County, North Carolina, where White was born. It aims to educate people about him and the achievements of people from the Farmers' Union community in Columbus and Bladen counties.

See also