Jaybird–Woodpecker War facts for kids

| Date | 1888–89 |

|---|---|

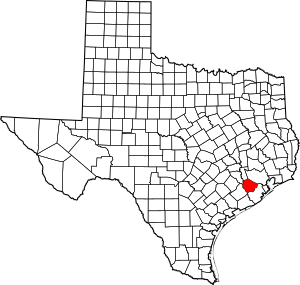

| Location | Fort Bend County, Texas, United States |

| Outcome | Jaybird victory |

| Deaths | 7 |

The Jaybird–Woodpecker War (1888–89) was a fight between two groups of people in the Democratic Party in Fort Bend County, Texas. They were battling for control of the local government. The Jay Bird Democratic Association was a group of young White men formed in 1887. They wanted to take back control from the Woodpeckers. The Woodpeckers were a mix of White and Black Republicans who had been in charge since 1869.

During 1888 and 1889, there were killings and attacks on people from both sides.

The Jaybird–Woodpecker War ended when the Jaybirds won a battle in Richmond, Texas, in August 1889. Richmond was the main town in Fort Bend County. With help from Texas Governor Lawrence Ross and the Houston Light Guards (a state militia group), the county government was completely changed. All Woodpecker officials had to leave or resign. Jaybirds, or people they approved of, took their places.

After more than 20 years, White citizens once again controlled the government. The effects of this conflict lasted for many decades in local politics. The Jaybird victory brought back White control in the county. They stopped Black voters from voting in party elections by using a "Whites-only" ballot. This practice lasted from 1889 until 1953. The Jaybird group and this voting rule spread to other counties. They stayed active until the Civil Rights Movement.

This "Whites-only" voting rule was challenged in court. In 1950, Willie Melton and Arizona Fleming won a lawsuit against it. But this decision was later overturned. Finally, in 1953, they won their case. The Supreme Court of the United States said the Jaybird primary was against the law in a case called Terry v. Adams. This was the last of the "white primary" cases.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

The reasons for the Jaybird–Woodpecker violence go back to the time before the American Civil War. This was when large farms called plantations were common in Fort Bend County. The fight over slavery greatly affected how the war began and how it shaped Fort Bend's politics and social life for over 100 years.

Life on Plantations Before the Civil War

Fort Bend County was settled by families from the "Old 300." These families bought land from Stephen F. Austin and the Mexican government in the 1820s. Before the Civil War, Fort Bend County became one of the biggest and richest slave-owning areas in Texas. Black enslaved people were brought there by White colonists or illegally shipped to Galveston, Texas. Slavery was against Mexican law until Texas became a republic in 1836.

Slavery was key to these plantations. Enslaved people were forced to work on farms growing cotton, sugarcane, and corn. As the demand for these crops grew, the number of enslaved people increased. It went from 1,559 in 1850 to 4,127 in 1860. The slave owners controlled the economy and politics of Fort Bend. They were at the top of society. In February 1861, all White male voters in the county voted to leave the United States and join the Confederacy.

Over 100 men from Fort Bend County joined a new group of soldiers called Colonel Benjamin Terry's Texas Rangers. Interestingly, his son, Kyle Terry, who was five years old then, became a leader 30 years later in the Jaybird–Woodpecker War. But unlike his father, Kyle Terry supported the Woodpeckers against the Jaybirds.

Fort Bend County After the Civil War

After the Civil War, the 13th Amendment was passed in 1864. This made millions of enslaved people free. In Fort Bend County, this meant that Black people, who made up over 80% of the population, were now free. The 15th Amendment in 1870 gave Black men the right to vote. This made them a strong voting group for the Republican Party.

Because Black men outnumbered White men, their votes decided most elections during Reconstruction. This was the time after the Civil War when Texas was under military rule. It was slowly rejoining the United States. Also, the large plantations were broken into smaller pieces of land. Many of these were bought by new farmers from Europe or rented by Black sharecroppers.

Even though they lost some political and economic power, White plantation owners surprisingly worked with the mixed-race county government during Reconstruction. Between 1869 and 1889, 44 Black men held different jobs in Fort Bend County. These included sheriff, county commissioner, justice of the peace, and constable. At one point, more than half of the county offices were held by Black politicians. They were supported by a few White people who were Republicans or independent Democrats. These White people did not support the all-White Democratic candidates in elections. Unlike other Texas counties, Fort Bend County actually had some racial cooperation and peace during this time.

Despite these changes, White people in Fort Bend kept their control over the county's economy and social life. White landowners owned over 80% of the land. This meant many people were tenant farmers or sharecroppers, as shown in the 1880 census. Local White people also created social rules to keep White and Black people separate. County schools were segregated. In 1882-1883, 193 White children went to one of five White-only schools. Meanwhile, 1,679 Black students went to one of 30 Black-only schools. Groups of citizens also formed to keep Black people "in order." They especially tried to stop social mixing between Black and White people.

Growing Tensions

The Jaybird–Woodpecker War was not bound to happen, but things were getting tense. Younger White men wanted to bring back White control. Also, the Democratic Party was gaining strength across the country in the late 1880s. This created a very emotional political mood in Fort Bend County.

Within the White community, tensions grew between those who supported the mixed-race government and those who were frustrated. The White people who supported the current politicians wanted things to stay the same. Most White people were angry at the independent Democrats for supporting Black people's right to vote and hold office. They also wanted more political power for themselves. They were upset about high taxes, some of which went to officeholders. With these feelings growing in the mid-to-late 1880s, many young men in Fort Bend County were tired of not being able to change county politics through voting. They formed the Jay Bird Democratic Association in July 1888.

The Conflict Begins

The conflict supposedly got its name from Bob Chapel, a local African-American man. He was said to sing about jaybirds and woodpeckers. The Jaybirds were White Democrats who did not want Black people involved in local politics. This was because a group of Black and White people (who used to be Republicans) had elected county officials for 20 years since Reconstruction. The Woodpeckers were also Democrats, but their leaders were mostly elected by Black voters.

An election was held on November 6, 1888. Texas Rangers watched over it. All the Woodpecker candidates won or were re-elected. Many had won elections in 1884. This made the Jaybirds even more angry.

In the spring of 1889, Kyle Terry, a Woodpecker official who was the tax assessor, killed Ned Gibson. Ned Gibson was a leader of the Jaybirds. Gibson had been on his way to testify in a trial against a friend of Terry's. Terry was arrested but paid bail and moved to Galveston. On January 21, 1890, Gibson's brother, Volney Gibson, and a group of Jaybirds shot Terry. This happened as Terry was walking up the stairs to the Galveston courtroom for his hearing about Ned Gibson's murder.

People from both sides were killed in revenge. This included the local sheriff, Tom Garvey (a Woodpecker), who was killed in 1889. The violence reached its peak in the Battle of Richmond on August 16, 1889, when Sheriff Garvey was killed. Seven people died in total during these events.

After this, Governor Sul Ross declared martial law. This meant the military took control. He sent troops from the Houston Light Guards and more Texas Rangers. Governor Ross arrived to help settle the conflict. After the violence calmed down, most of the county government officials resigned. When it came to finding new officials, only the Jaybird politicians had enough money to pay the required bonds for the open jobs. The Jaybirds refused to pay bonds for anyone from the other side. So, the county government was reorganized under the control of the Jaybird group. This was made official at a meeting on October 3, 1889. The former officeholders were told to leave town.

Later, on October 22, 1889, the Jaybirds held another meeting. They created the Jaybird Democratic Organization of Fort Bend County. This group controlled local politics for decades, until the 1950s. The group set up a "White-only" preliminary ballot for county offices. This effectively stopped African Americans from voting in important elections. This was because the only real competition was within the Democratic Party. A similar "White primary" rule was also adopted by the state government in the early 1900s.

The Jaybird Democrats stayed in control until their rule was overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States in the case Terry v. Adams in 1953. By that time, two other "White primary" processes allowed by the state government had already been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. The second one was in the case Smith v. Allwright in 1944.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |