Rosewood massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rosewood massacre |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the nadir of American race relations | |

| Coordinates | 29°14′0″N 82°56′0″W / 29.23333°N 82.93333°W |

| Date | January 1–7, 1923 |

| Target | Black people |

| Deaths | 6 black and 2 white people (official figure) 27 to 150 in some reports |

The Rosewood massacre was a terrible event where a black town was destroyed and many black people were killed. It happened in the first week of January 1923 in a rural area of Levy County, Florida. At least six black people and two white people died, but some people who saw it happen said the number was much higher, perhaps between 27 and 150. The town of Rosewood was completely destroyed. News reports at the time called it a "race riot."

Before this event, Rosewood was a peaceful, mostly black town. It was a whistle stop (a small train stop) on the Seaboard Air Line Railway. The trouble started when a white woman in nearby Sumner claimed a black man had attacked her. White men from several towns formed a mob. They hunted for black people and burned almost every building in Rosewood. For several days, people who survived hid in swamps nearby. They were later taken to bigger towns by train and car. No one was arrested for what happened in Rosewood. The town was left empty, and no one ever moved back or received money for their lost land.

Even though many newspapers reported on the events, there were not many official records. The people who survived, their families, and those who caused the violence stayed silent for many years. Sixty years later, journalists brought the story of Rosewood back into the news. Survivors and their families sued the state of Florida. They said the state failed to protect the black community of Rosewood. In 1993, the Florida Legislature ordered a report about the event. Because of what the report found, Florida paid money to the survivors and their families. This was to make up for the harm caused by the violence. A movie called Rosewood was made about the event in 1997. In 2004, the site of Rosewood was named a Florida Heritage Landmark.

Contents

What Happened in Rosewood?

How Rosewood Began

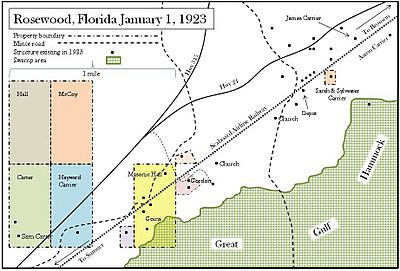

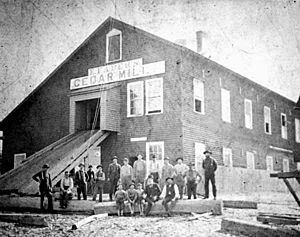

Rosewood was founded in 1847. It was about nine miles (14 km) east of Cedar Key, near the Gulf of Mexico. Most people in the area worked in the timber industry. The town's name, Rosewood, came from the reddish color of cedar wood. Two pencil mills were in Cedar Key. People also worked in turpentine mills and a sawmill in Sumner. Some residents farmed citrus and cotton.

Rosewood grew enough to get a post office and a train station in 1870. It was never officially made a town. At first, both black and white people lived in Rosewood. By 1890, most of the cedar trees were cut down. The pencil mills closed, and many white residents moved to Sumner. By 1900, most people in Rosewood were black. Sumner was mostly white, but the two communities generally got along.

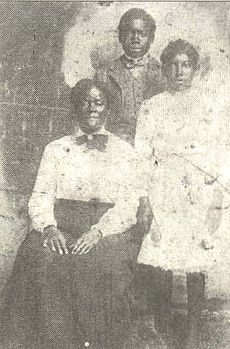

Two black families, the Goins and Carrier families, were very important in Rosewood. The Goins family brought the turpentine business to the area. They owned a lot of land. The Carriers were also a large family, working in logging. By the 1920s, almost everyone in Rosewood was related. The town was a close-knit community. Rosewood had its largest population in 1915 with 355 people.

Florida had laws called Jim Crow laws that kept black and white people separate. This was called racial segregation. Black and white people had their own community places. By 1920, Rosewood residents were mostly self-sufficient. They had three churches, a school, a large Masonic Hall, a turpentine mill, a sugarcane mill, and two general stores. They even had a baseball team called the Rosewood Stars. Many families owned pianos and organs. Survivors remember Rosewood as a happy place.

Tensions Before the Attack

Racial violence was common across the U.S. at this time. Lynchings (when a mob kills someone, often by hanging, without a trial) were very common in the South. White supremacists used them to control black people. Florida, like other Southern states, passed laws to stop black citizens from voting. This meant black people had little power in politics. They could not be jurors or run for office.

Many black Americans moved North during and after World War I. This was called the Great Migration. They sought better jobs and to escape unfair treatment. Florida governors often ignored this movement. They did not investigate lynchings. Governor Sidney Catts openly criticized the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) for complaining about lynchings. Later, he asked black workers to stay when industries needed them.

Between 1917 and 1923, racial problems happened in many U.S. cities. This was often due to competition for jobs. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a white supremacist group, grew very strong in the 1920s. They were active in Florida cities like Jacksonville and Tampa. Even in smaller towns, white mob violence was common and often ignored by police. Just weeks before Rosewood, a similar event happened in Perry, Florida. White people attacked the black community there after a white schoolteacher was killed.

Fannie Taylor's Story

The Rosewood massacre started after a white woman in Sumner, Fannie Taylor, claimed she was attacked by a black man. Fannie was 22 years old in 1923. She lived with her husband, James, and their two young children. James worked at a mill and left for work very early. Neighbors said Fannie Taylor was "very peculiar" and kept her house extremely clean.

On January 1, 1923, a neighbor heard a scream from Fannie's house. She found Fannie bruised and beaten. Fannie said a black man had come into her house and attacked her. The neighbor found the baby, but no one else. The day before, the Klan had a parade 50 miles (80 km) away in Gainesville. They had a burning cross and a sign saying, "First and Always Protect Womanhood."

Fannie's laundress, Sarah Carrier, was not there that day. Sarah's granddaughter, Philomena Goins, later told a different story. She said she was with her grandmother at Fannie Taylor's house that morning. They saw a white man leave by the back door before noon. Philomena said Fannie Taylor did appear beaten, but it was later in the morning. The black community in Rosewood believed Fannie Taylor had a white lover. They thought they had a fight, and he beat her. When the man left, he went to Rosewood.

Sheriff Robert Elias Walker quickly started an investigation. They looked for Jesse Hunter, a black prisoner who had escaped. Men from nearby towns joined the search. About 400 white men gathered. Sheriff Walker deputized some of them, but many acted on their own. Some men used dogs to track a scent to the home of Aaron Carrier, Sarah's nephew. Aaron was taken and dragged to Sumner. Sheriff Walker put Aaron in protective custody in Bronson to keep him safe from the angry mob.

A group of white men, now a mob, grabbed Sam Carter. He was a local blacksmith. They forced Carter to say he had hidden the escaped prisoner. Carter led them to a spot in the woods, but the dogs found no scent. Some people believe Fannie Taylor's lover fled to Rosewood. He went to Aaron Carrier's home. Carrier and Carter, who were both Masons, helped the man hide. Carter took him to a river. When Carter returned, the mob was waiting.

After killing Sam Carter, the mob met Sylvester Carrier, Aaron's cousin and Sarah's son. They told him to leave town. Carrier refused. He suggested that people gather for protection.

The Violence Grows

Even though Sheriff Walker tried to stop the mobs, more white men gathered. On the evening of January 4, an armed mob went to Rosewood. They surrounded Sarah Carrier's house. About 15 to 25 people were inside, many of them children hiding upstairs. They were protected by Sylvester Carrier, who was known for being proud and a good shot. He was called "Man" in Rosewood. Many white people thought he was arrogant.

Reports say Sylvester Carrier made a statement that angered the mob. A group of 20 to 30 white men went to the Carrier house. They believed the black community was hiding Jesse Hunter.

It's unclear who shot first. But after two mob members approached the house, shots were fired. Sarah Carrier was shot in the head. Minnie Lee Langley, a nine-year-old niece, was there. Sylvester used a firewood closet for cover. He put his gun on Minnie Lee's shoulder. When Poly Wilkerson kicked the door down, Sylvester shot him.

Many shots were fired. The house was full of bullet holes, but the white mob did not take it over. The fight lasted until the next morning. Sarah and Sylvester Carrier were found dead inside. Several others were hurt, including a child shot in the eye. Two white men, Poly Wilkerson and Henry Andrews, were killed. At least four white men were wounded. The remaining children in the Carrier house escaped out the back door into the woods. They hid until they were all together away from Rosewood.

Burning Rosewood

News of the fight at the Carrier house brought white men from all over the state. Newspapers like The New York Times and The Washington Post reported on the event. They often described "heavily armed Negroes" and a "negro desperado." Most information came from Sheriff Walker's messages and mob rumors. The idea that black people in Rosewood fought back against white people was shocking in the South.

Black newspapers told the story differently. The Afro-American newspaper highlighted acts of African-American bravery.

The white mob burned black churches in Rosewood. Philomena Goins' cousin, Lee Ruth Davis, heard the church bells ringing as men set it on fire. The mob also destroyed the white church in Rosewood. Many black residents ran into the nearby swamps. Some were only in their pajamas. Wilson Hall, who was nine, remembered his mother waking him to escape into the swamps in the dark. The Hall family walked 15 miles (24 km) through the swamp to Gulf Hammock. It was very cold, and people suffered hiding in the swamps. Some found help from white families who felt sympathy for them.

White men began surrounding houses. They poured kerosene on them and set them on fire. Then they shot at anyone who came out. Lexie Gordon, a 50-year-old woman who was sick, had sent her children into the woods. She was killed when she ran from her burning home. Fannie Taylor's brother-in-law claimed he killed her. On January 5, the mob grew to between 200 and 300 people. Some came from other states. Mingo Williams, who was 20 miles (32 km) away, was shot dead by white men who stopped their car and asked his name.

Sheriff Walker asked for help from the Alachua County Sheriff. Carloads of men from Gainesville came to help Walker. Many had been at the Klan rally earlier. W. H. Pillsbury, a mill supervisor, tried to keep black workers safe. He also worked to stop white workers from joining the mob. Armed guards sent by Sheriff Walker turned away black people trying to return home from the swamps. Pillsbury's wife secretly helped people escape. Some white men refused to join the mobs.

Governor Cary Hardee was ready to send in the National Guard. But Sheriff Walker told him he did not expect "further disorder." He asked the governor not to get involved. The governor's office watched the situation, but Hardee did not send the National Guard without Walker's request. Records show Governor Hardee trusted Sheriff Walker and went on a hunting trip.

James Carrier, Sylvester's brother, had a stroke and was partly paralyzed. He left the swamps and went back to Rosewood. He asked W. H. Pillsbury for protection. Pillsbury locked him in a house, but the mob found Carrier. They forced him to dig his own grave, then shot him.

Escaping Rosewood

On January 6, white train conductors John and William Bryce helped some black residents escape to Gainesville. The brothers knew the people in Rosewood. They slowed their train and blew the horn, picking up women and children. They were afraid of the mobs, so they did not pick up any black men. Many survivors got on the train after being hidden by John Wright, a white general store owner, and his wife, Mary Jo. Over the next few days, other Rosewood residents fled to the Wrights' house. Sheriff Walker asked Wright to help transport as many people out of town as possible.

Lee Ruth Davis and her siblings were hidden by the Wrights. Their father hid in the woods. On the day of Poly Wilkerson's funeral, the Wrights left the children alone to attend. Davis and her siblings tried to hide with relatives in Wylly, but they were turned away. The children spent the day in the woods. They decided to go back to the Wrights' house. They saw men with guns on their way back. They crept back to the Wrights, who were very worried. Davis later said, "I was laying that deep in water, that is where we sat all day long... We got on our bellies and crawled. We tried to keep people from seeing us through the bushes... We were trying to get back to Mr. Wright house."

Several other white residents of Sumner also hid black residents of Rosewood. They helped them escape. Gainesville's black community welcomed many of Rosewood's survivors. They waited at the train station and greeted them as they arrived. On Sunday, January 7, a mob of 100 to 150 white people returned. They burned the last dozen or so buildings in Rosewood.

The Silence and Remembering Rosewood

Years of Silence

Even with news coverage, the event and the abandoned village were forgotten. Most survivors moved to other Florida cities and started over with nothing. Many, including children, took odd jobs to survive. They often had to give up school to earn money. Most Rosewood survivors worked as maids, shoe shiners, or in factories.

The survivors did not talk publicly about what happened. Robie Mortin was seven when her father put her on a train in 1923. Her family never spoke about Rosewood. Her grandmother told them not to. "She felt like maybe if somebody knew where we came from, they might come at us," Mortin said.

Minnie Lee Langley kept the story from her children for 60 years. "I didn't want them to know what I came through," she said. She did not want them to know "white folks want us out of our homes." It took decades for her to trust white people. Some families talked about Rosewood, but told their children not to share the stories. Arnett Doctor heard the story from his mother, Philomena Goins Doctor. She told her children about Rosewood every Christmas.

In 1982, a reporter named Gary Moore from the St. Petersburg Times heard about the massacre. He convinced Arnett Doctor to visit the site. Moore wrote about how the event had disappeared from history. "After a week of sensation, the weeks of January 1923 seem to have dropped completely from Florida's consciousness," he wrote.

When Philomena Goins Doctor found out, she was very angry. A year later, Moore's story was featured on CBS' 60 Minutes. Philomena Doctor called her family and said the story was full of lies. A psychologist later said that Rosewood survivors showed signs of posttraumatic stress disorder. This was made worse by the secrecy. Many years later, they still showed fear and avoided white people. But survivors said their religious faith helped them not to be bitter.

The memory of Rosewood stayed in Levy County. For decades, no black residents lived in Cedar Key or Sumner. Robin Raftis, a newspaper editor, tried to print Moore's story. She received threats. University of Florida historian David Colburn said people denied what happened. They did not want to talk about it or name anyone involved.

In 1993, a black couple moved to Rosewood. They told The Washington Post, "When we used to have black friends down from Chiefland, they always wanted to leave before it got dark." They did not want to be in Rosewood after dark.

Seeking Justice

Philomena Goins Doctor died in 1991. Her son Arnett became very interested in the Rosewood events. A large law firm took on the case for free. In 1993, they filed a lawsuit for Arnett Goins, Minnie Lee Langley, and other survivors. They sued the state for not protecting them.

Survivors shared their stories to get more attention. Langley and Lee Ruth Davis appeared on The Maury Povich Show in 1993. Gary Moore published another article in the Miami Herald. At first, editors were doubtful. "If something like that really happened, we figured, it would be all over the history books," an editor wrote.

Arnett Doctor told the Rosewood story to reporters from around the world. He sometimes made the numbers of residents and deaths higher. He wanted to keep Rosewood in the news. His stories put pressure on the state government. In 1996, Doctor said 30 women and children were buried alive. He was embarrassed when Gary Moore, the journalist, was in the audience. The law firm represented 13 survivors in the claim to the legislature.

The lawsuit missed a deadline. So, the speaker of the Florida House of Representatives asked a group to research the event. Historians from three universities wrote a 100-page report in 1993. It was based on documents and interviews with black survivors. White people did not give interviews. The report was called "Documented History of the Incident which Occurred at Rosewood, Florida in January 1923."

Rosewood Remembered

In Books and Film

The Rosewood massacre, the silence that followed, and the compensation hearings were written about in the 1996 book Like Judgment Day: The Ruin and Redemption of a Town Called Rosewood by Mike D'Orso. It became a bestseller and won an award.

The movie Rosewood (1997), directed by John Singleton, was based on these events. Minnie Lee Langley helped with the set design. Arnett Doctor was a consultant. The towns of Rosewood and Sumner were rebuilt for the movie. The film added a character named Mann, a hero who helps the people of Rosewood. The movie shows a happy past for black families and a black hero who fights back. Singleton said he wanted to deal with the "horror and evil that black people have faced in this country."

The movie received mixed reviews. Some said it made up too much of the story. Gary Moore felt the movie was not accurate. He said it made the death toll too high. Others, like Stanley Crouch, called it Singleton's best work. He said it clearly showed "Southern racist hysteria."

Rosewood's Legacy

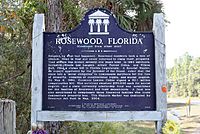

In 2004, the State of Florida named Rosewood a Florida Heritage Landmark. A historical marker was put up on Florida State Road 24. It lists the victims and describes the town's destruction. A few buildings still stand, including a church, a business, and John Wright's house. Mary Hall Daniels, the last known survivor, died in 2018 at age 98. Vera Goins-Hamilton, another survivor, died in 2020 at age 100.

Descendants of Rosewood families created the Rosewood Heritage Foundation and the Real Rosewood Foundation. They want to teach people about the massacre. The Rosewood Heritage Foundation has a traveling exhibit. A permanent display is at Bethune-Cookman University. The Real Rosewood Foundation gives awards to people who help preserve Rosewood's history. They also honored white residents who protected black people during the attacks. Lizzie Jenkins, a leader of the Real Rosewood Foundation, said, "It's a sad story, but it's one I think everyone needs to hear."

In 2020, Florida started the Rosewood Family Scholarship Program. It pays up to $6,100 each year for up to 50 students who are direct descendants of Rosewood families.

See also

In Spanish: Masacre de Rosewood para niños

In Spanish: Masacre de Rosewood para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |