History of Atlanta facts for kids

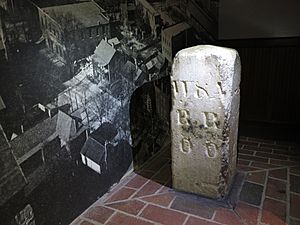

The history of Atlanta began in 1836. That year, the state of Georgia decided to build a railroad to the Midwest. A spot was chosen to be the end of the line, called "Terminus." The first stake was driven into the ground in 1837. This spot is now known as the Zero Mile Post.

By 1839, homes and a store were built there, and the settlement grew. Between 1845 and 1854, train tracks arrived from four different directions. The fast-growing town quickly became a major train center for the entire Southern United States.

During the American Civil War, Atlanta was a key supply hub. Because of this, it became a target for the Union Army. In 1864, Union General William Sherman's troops burned and destroyed most of the city. Only churches and hospitals were saved.

After the war, Atlanta's population grew quickly. Factories also grew, and the city remained a major train hub. Coca-Cola started here in 1886 and became a huge global company based in Atlanta. Electric streetcars arrived in 1889, leading to new neighborhoods called "streetcar suburbs."

Atlanta's important Black colleges were founded between 1865 and 1885. Even with laws like Jim Crow in the 1910s, a successful Black middle class and upper class developed. By the early 1900s, "Sweet" Auburn Avenue was known as "the most prosperous Negro street in the nation."

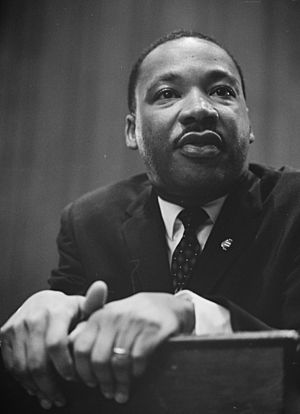

In the 1950s, Black people began moving into city neighborhoods that had been closed to them. At the same time, Atlanta's first freeways allowed many white residents to move to new suburbs and drive into the city for work. Atlanta was home to Martin Luther King Jr., and a key center for the Civil Rights Movement. Segregation ended step by step during the 1960s. Old, run-down areas were cleared, and the new Atlanta Housing Authority built public housing projects.

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, nine suburban malls opened. This caused downtown shopping to decline. However, just north of downtown, tall office buildings and hotels were built. In 1976, the new Georgia World Congress Center showed Atlanta was becoming a major convention city.

In 1973, the city elected its first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson. In the years that followed, Black political leaders worked well with white business leaders. They helped businesses grow while also supporting Black-owned businesses. From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, most of the MARTA train system was built. While the suburbs grew fast, much of the city itself faced challenges. Atlanta lost 21% of its population between 1970 and 1990.

In 1996, Atlanta hosted the 1996 Summer Olympics. New buildings and roads were built for the event. The local airline, Delta, continued to grow. By 1998–99, Atlanta's airport was the busiest in the world. Since the mid-1990s, gentrification has brought new life to many of the city's inner neighborhoods. The 2010 census showed that affluent Black people were moving to newer suburban areas. Younger white people were moving back into the city. The wider metropolitan area became much more diverse, with the fastest growth happening in the outer suburbs.

Contents

- Early History: Before 1836

- From Terminus to Atlanta: 1836-1860

- Civil War and Rebuilding: 1861-1871

- "Gate City of the New South": 1872-1905

- Streetcar Suburbs and World War II: 1906-1945

- Suburban Growth and Civil Rights: 1946-1989

- Neighborhood Changes and Racial Transition

- Civil Rights Movement

- Ending Segregation

- 1962 Air Crash and Its Impact on Arts

- Freeway Construction and Protests

- Urban Renewal

- Shoppers Move to Malls, Downtown Changes

- Black Political Power and Mayor Jackson

- Building the MARTA Rail System

- Mayor Andrew Young

- Olympic and World City: 1990-Present

Early History: Before 1836

The land where Atlanta and its suburbs now stand was originally home to Creek and Cherokee Native American tribes. In 1813, the Creeks, who were helping the British in the War of 1812, attacked and burned Fort Mims in Alabama. This conflict grew into the Creek War.

In response, the United States built forts along the Ocmulgee and Chattahoochee Rivers. One of these was Fort Gilmer, near an important Native American meeting place called Standing Peachtree. This place was named after a large pine tree. The name "pitch" (from the tree's sap) was misunderstood as "peach," leading to the name. This spot marked the border between Creek and Cherokee lands, where Peachtree Creek flows into the Chattahoochee. Fort Gilmer was soon renamed Fort Peachtree. A road was built connecting Fort Peachtree and Fort Daniel, following old trails.

As part of a plan to move Native Americans from northern Georgia, the Creek tribe gave up the area that is now Metro Atlanta in 1821. A few months later, new counties were created in the area. DeKalb County was formed in 1822, and Decatur became its county seat. Archibald Holland received a land grant where downtown Atlanta would later be built. He farmed the land, but it was often muddy. He left the area in 1833.

In 1830, an inn was built that became known as Whitehall because it was painted white, which was unusual then. Later, Whitehall Street was built as a road from Atlanta to Whitehall. The Whitehall area was renamed West End in 1867. It is Atlanta's oldest neighborhood with many original Victorian homes.

In 1835, some Cherokee leaders signed the Treaty of New Echota. This treaty gave their land to the United States without the agreement of most Cherokee people. This event later led to the sad journey known as the Trail of Tears.

From Terminus to Atlanta: 1836-1860

In 1836, the Georgia General Assembly decided to build the Western and Atlantic Railroad. This railroad would connect the port of Savannah to the Midwest. The train line was planned to run from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to a spot east of the Chattahoochee River in what is now Fulton County. The goal was to link up with other railroads.

In 1837, a U.S. Army engineer, Colonel Stephen Harriman Long, chose the exact spot for the railroad to end. He drove a stake into the ground. This spot is now marked by the zero milepost.

In 1839, John Thrasher built homes and a general store nearby. The settlement was called Thrasherville. An old earthen wall, the Monroe Embankment, built by Thrasher, is the oldest man-made structure still existing in Downtown Atlanta.

In 1842, the planned end point for the railroad was moved. It moved to what would become State Square. The zero milepost is now found here, near Underground Atlanta. As the settlement grew, it was known as "Terminus," meaning "end of the line." By 1842, Terminus had six buildings and 30 residents.

Meanwhile, another settlement began in what is now the Buckhead area, north of downtown. In 1838, Henry Irby opened a tavern and grocery there.

In 1842, a two-story brick train depot was built. Locals asked to name the settlement Lumpkin, after Governor Wilson Lumpkin. But Governor Lumpkin asked them to name it after his daughter instead. So, Terminus became Marthasville. In 1845, the chief engineer of the Georgia Railroad suggested renaming Marthasville "Atlantica-Pacifica." This was quickly shortened to "Atlanta." The residents liked the name, even though no train had arrived yet. The town of Atlanta was officially created in 1847.

Growing into a Major Rail Hub

The first Georgia Railroad trains from Augusta arrived in September 1845. That year, the first hotel, the Atlanta Hotel, opened.

In 1846, a second railroad, the Macon and Western Railroad, connected Atlanta to Macon and Savannah. The town began to boom. By 1847, the population reached 2,500. In 1848, Atlanta elected its first mayor. In 1849, the Trout House hotel was built, and the Daily Intelligencer became the town's first successful daily newspaper. In 1850, Oakland Cemetery was founded.

In 1851, the Western and Atlantic Railroad finally arrived. This connected Atlanta to Chattanooga and opened up trade with the Tennessee and Ohio River Valleys. The union depot was finished in 1853.

Fulton County was created in 1853. In 1854, a building for both the Fulton County Court House and Atlanta City Hall was built. After the Civil War, Atlanta became the state capital of Georgia.

In 1854, a fourth train line, the Atlanta and LaGrange Rail Road, arrived. This connected Atlanta with LaGrange, Georgia to the southwest. This made Atlanta a complete rail hub for the entire South.

By 1855, the town had grown to 6,025 residents. It had a bank, a newspaper, a factory for train cars, a new depot, and gas street lights.

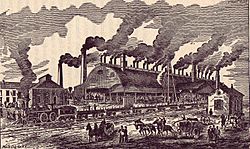

Factories and Businesses

The first factory opened in 1844 when Jonathan Norcross built a sawmill. Others built a flour mill, which was used to make pistols during the Civil War. In 1848, Austin Leyden started the town's first metalworking shop.

The Atlanta Rolling Mill was built in 1858. It became the South's second most productive mill. During the American Civil War, it made cannons and iron sheets for ships. The mill was destroyed by the Union Army in 1864.

Atlanta became a busy center for cotton distribution. For example, in 1859, the Georgia Railroad sent 3,000 empty train cars to the city to be filled with cotton.

By 1860, the city had several large machine shops, mills, tanneries, and clothing factories.

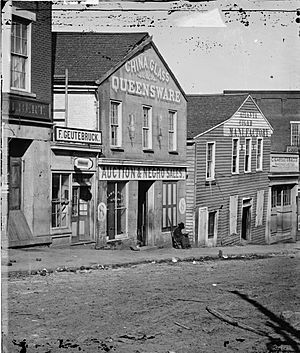

Slavery in Early Atlanta

In 1850, out of 2,572 people, 493 were enslaved African Americans. There were also 18 free Black people. This meant about 20% of the population was Black. After the Civil War, this number would grow much higher as freed slaves came to Atlanta looking for opportunities.

There were several slave auction houses in the town. They advertised in newspapers and also traded in manufactured goods.

Civil War and Rebuilding: 1861-1871

The Civil War: 1861-1865

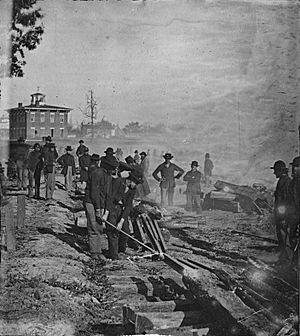

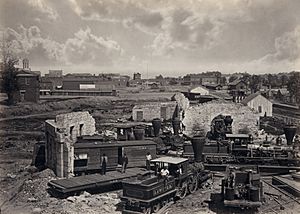

During the American Civil War, Atlanta was an important railroad and military supply center. In 1864, the city became the target of a major Union attack. The area around Atlanta saw several battles, including the Battle of Peachtree Creek, the Battle of Atlanta, and the Battle of Ezra Church.

General Sherman cut the last supply line to Atlanta at the Battle of Jonesboro on August 31-September 1. With no supplies left, Confederate General John Bell Hood had to leave Atlanta. On the night of September 1, his troops marched out of the city. General Hood ordered 81 train cars full of ammunition and supplies to be destroyed. The fires and explosions were heard for miles.

The next day, Mayor James Calhoun surrendered the city. On September 7, Sherman ordered all civilians to leave. He then ordered Atlanta burned to the ground on November 11. This was in preparation for his march south.

After a plea from Father Thomas O'Reilly, Sherman did not burn the city's churches or hospitals. The remaining war resources were destroyed. The fall of Atlanta was a very important moment in the Civil War. Its capture gave confidence to the Northerners. Along with another battle, the fall of Atlanta helped Abraham Lincoln get re-elected and led to the Confederacy's eventual surrender.

Reconstruction: 1865-1871

The city rose from the ashes, like the mythical phoenix, which is now the city's symbol. Atlanta was gradually rebuilt, and its population grew quickly after the war. Many people moved to Atlanta from nearby areas. From 1860 to 1870, Fulton County's population more than doubled. Many freed slaves moved from plantations to cities like Atlanta to find work. Fulton County went from 20.5% Black in 1860 to 45.7% Black in 1870.

Food supplies were difficult to get due to poor harvests. Many refugees had no proper clothing or shoes. Groups like the AMA and the Freedmen's Bureau helped with food, shelter, and clothing.

The destruction of homes by the Union army and the large number of refugees caused a severe housing shortage. Small lots with a house rented for $5 a month, while those with glass windows rented for $20. High rents, rather than laws, led to segregation. Most Black residents settled in three poor areas at the city's edge. These homes were often "rickety shacks" rented at high prices. Two of these areas were low-lying and prone to flooding, leading to disease outbreaks.

A smallpox epidemic hit Atlanta in December 1865. There were not enough doctors or hospitals. Another epidemic hit in Fall 1866, killing hundreds.

Construction created many new jobs, and employment boomed. Atlanta quickly became the industrial and business center of the South. From 1867 to 1888, U.S. Army soldiers were stationed in southwest Atlanta to help with Reconstruction. In 1868, Atlanta became the state capital of Georgia, taking over from Milledgeville.

Center for Black Education

Atlanta quickly became a hub for Black education. Atlanta University was founded in 1865. The school that became Morehouse College started in 1867. Clark University began in 1869. What is now Spelman College opened in 1881, and Morris Brown College in 1885. These schools helped create one of the nation's oldest and most respected African American elite communities in Atlanta.

"Gate City of the New South": 1872-1905

The New South

Henry W. Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution newspaper, promoted Atlanta to investors as a city of the "New South." He meant that the economy was moving away from farming and slavery. To modernize the South, Grady and others supported creating the Georgia School of Technology (now Georgia Tech). It was founded in 1885.

In 1880, Sister Cecilia Carroll and three companions came to Atlanta to care for the sick. With only 50 cents, they opened the Atlanta Hospital, the city's first medical facility after the Civil War. This later became Saint Joseph's Hospital.

City Expansion and New Neighborhoods

Starting in 1871, horse-drawn streetcars, and later electric streetcars (from 1888), helped real estate grow and the city expand. Washington Street south of downtown and Peachtree Street north of downtown became wealthy residential areas.

In the 1890s, West End was a popular suburb for the city's wealthy. But Inman Park, designed as a beautiful, planned community, soon became even more prestigious. Large mansions on Peachtree Street stretched further north into what is now Midtown Atlanta.

Atlanta became Georgia's largest city by 1880, surpassing Savannah.

Voting Rights for Black Citizens

As Atlanta grew, tensions between different groups increased. After Reconstruction, white leaders used various methods to regain political and social control throughout the South. Starting with a poll tax in 1877, Georgia passed laws that took away voting rights from Black citizens. Even educated Black men could not vote. Despite this, African Americans in Atlanta developed their own businesses, churches, and a strong, educated middle class.

Coca-Cola's Story

Atlanta and Coca-Cola have been linked since 1886. That year, John Pemberton created the soft drink because Atlanta and Fulton County had banned alcohol. The first sales were at Jacob's Pharmacy in Atlanta. Asa Griggs Candler bought a share in Pemberton's company in 1887. By its 50th anniversary, Coca-Cola was a national symbol in the USA. Coca-Cola's world headquarters have always been in Atlanta. In 1991, the company opened the World of Coca-Cola, which is still a top attraction.

Cotton States Expo and Booker T. Washington

In 1895, the Cotton States and International Exposition was held at what is now Piedmont Park. Nearly 800,000 people visited. The event aimed to promote the region to the world, show new products and technologies, and encourage trade. President Grover Cleveland opened the exposition.

The event is best remembered for the ""Atlanta Compromise" speech" given by Booker T. Washington. In his speech, he suggested that Southern Black people would work hard and accept white political rule. In return, Southern white people would ensure Black people received basic education and fair legal treatment.

Streetcar Suburbs and World War II: 1906-1945

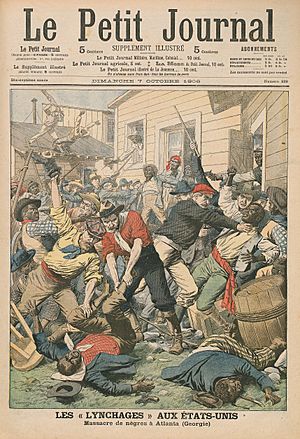

1906 Race Riot and Its Effects

Competition for jobs and housing between working-class white and Black people caused fears and tensions. In 1906, newspapers helped trigger the Atlanta Race Riot. At least 27 people died (25 of them Black), and over 70 were injured.

The Rise of Sweet Auburn

After the riot, Black businesses began moving from downtown to safer areas. These included the area around the Atlanta University Center and Auburn Avenue in the Old Fourth Ward. "Sweet" Auburn Avenue became home to Alonzo Herndon's Atlanta Mutual, the city's first Black-owned life insurance company. It also became known for its many Black businesses, newspapers, churches, and nightclubs. In 1956, Fortune magazine called Sweet Auburn "the richest Negro street in the world." Sweet Auburn and Atlanta's elite Black colleges became the heart of a successful Black middle and upper class. This happened despite huge social and legal challenges.

Jim Crow Laws

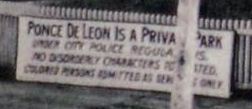

Jim Crow laws were passed quickly after the riot. These laws often led to segregated facilities, which were almost always worse for Black customers. In many cases, there were no facilities at all available to Black people. For example, all public parks were designated for whites only. In 1910, the city council passed a law requiring restaurants to serve only one race. This hurt Black restaurant owners who had served both Black and white customers. In the same year, Atlanta's streetcars were segregated. Black passengers had to sit in the back. If there were not enough seats for white riders, Black riders in the front had to stand and give up their seats. In 1913, the city created official boundaries for white and Black residential areas. In 1920, the city banned Black-owned salons from serving white women and children.

Beyond these laws, Black people had to follow strict racial rules. They had to show respect to all white people, even those of lower social standing. Black people were required to call white people "sir," but rarely received the same courtesy. Even small breaks in these rules often led to violence.

Country Music Scene

Many people from the Appalachia region came to Atlanta to work in cotton mills. They brought their music with them. Starting with a fiddler's convention in 1913, Atlanta became a center for country music. Atlanta was important for recording country music and finding new talent in the 1920s and 1930s. It remained a live music center for two more decades.

Growth of the City

In 1914, Asa Griggs Candler, the founder of The Coca-Cola Company, convinced the Methodist Episcopal Church South to build the new campus of Emory University in the growing wealthy suburb of Druid Hills.

Great Atlanta Fire of 1917

On May 21, 1917, the Great Atlanta Fire destroyed 1,938 buildings, mostly wooden, in what is now the Old Fourth Ward. The fire left 10,000 people homeless. Only one person died, a woman who had a heart attack after seeing her home in ashes.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression affected Atlanta. The city government was almost bankrupt. The Coca-Cola Company had to help the city pay its debts. The federal government also helped Atlantans by building Techwood Homes, the nation's first federal housing project, in 1935.

Gone with the Wind Premiere

On December 15, 1939, Atlanta hosted the premiere of Gone with the Wind. The movie was based on Atlanta resident Margaret Mitchell's best-selling novel. Stars Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, and Olivia de Havilland attended. The premiere was held at Loew's Grand Theatre. A huge crowd of 300,000 people filled the streets on this cold night. A loud cheer greeted a group of Confederate veterans who were special guests.

Black Stars Not Present

Noticeably absent were Hattie McDaniel, who would win an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Mammy, and Butterfly McQueen (Prissy). The Black actors were not allowed to attend the premiere, appear in the souvenir program, or be in the film's advertising in the South. Director David Selznick tried to bring McDaniel to the premiere, but MGM advised him not to. Clark Gable angrily threatened to boycott the premiere, but McDaniel convinced him to attend anyway. McDaniel did attend the Hollywood debut 13 days later and was featured prominently there.

Transportation Hub

In 1941, Delta Air Lines moved its headquarters to Atlanta. Delta would become the world's largest airline in 2008.

World War II

When the United States entered World War II, soldiers from the Southeastern United States passed through Atlanta to train and later be discharged at Fort McPherson. War-related manufacturing, like the Bell Aircraft factory in Marietta, helped boost the city's population and economy. Shortly after the war in 1946, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was founded in Atlanta.

Suburban Growth and Civil Rights: 1946-1989

In 1951, Atlanta received the All-America City Award for its fast growth and high quality of life.

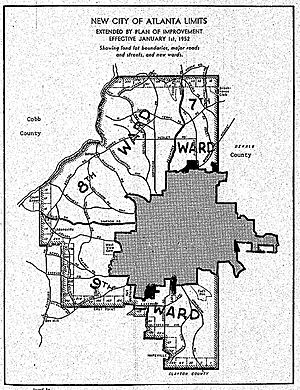

Growing the city by adding nearby areas was a key strategy. In 1952, Atlanta added Buckhead and large parts of northwest, southwest, and south Atlanta. This tripled its area. By doing so, 100,000 new wealthy white residents were added. This helped keep white political power and expanded the city's property tax base. Federal courts ended the control of rural Georgia over the state legislature. This allowed Atlanta and other cities to gain more political power. The federal courts also opened the Democratic Party primary to Black voters. Their numbers grew, and they became well-organized through the Atlanta Negro Voters League.

Neighborhood Changes and Racial Transition

In the late 1950s, after forced housing patterns were outlawed, some white neighborhoods used violence and pressure to discourage Black people from buying homes there. However, these efforts failed. By the late 1950s, a practice called blockbusting caused white residents to sell their homes in neighborhoods like Adamsville, Center Hill, and Grove Park in northwest Atlanta. White sections of Edgewood and Kirkwood on the east side also changed.

In 1961, the city tried to stop blockbusting by putting up road barriers in Cascade Heights. This went against the efforts of city leaders who wanted Atlanta to be known as "the city too busy to hate." But efforts to stop the change in Cascade also failed. Neighborhoods with new Black homeowners grew, helping to ease the huge shortage of housing for African Americans. Atlanta's western and southern neighborhoods became mostly Black. Between 1960 and 1970, the number of areas that were at least 90% Black tripled. Neighborhoods like East Lake, Kirkwood, and Cascade Heights changed almost completely from white to Black. The proportion of Black people in the city's population rose from 38% to 51%. At the same time, the city lost 60,000 white residents, a 20% decline.

White flight and the building of malls in the suburbs led to a slow decline of the downtown business district. Meanwhile, conservative views grew quickly in the suburbs, and people there increasingly voted for Republicans.

Civil Rights Movement

After the important U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, which helped start the Civil Rights Movement, racial tensions in Atlanta led to violence. For example, on October 12, 1958, a Reform Jewish temple on Peachtree Street was bombed. The "Confederate Underground" claimed responsibility. Many believed that Jewish people, especially from the Northeast, supported the Civil Rights Movement.

In the 1960s, Atlanta was a major center for organizing the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. Martin Luther King and students from Atlanta's historically Black colleges and universities played major roles in leading the movement. On October 19, 1960, a sit-in at lunch counters in several Atlanta department stores led to the arrest of Dr. King and several students. This brought attention from national news and from presidential candidate John F. Kennedy.

Despite this incident, Atlanta's political and business leaders promoted the city's image as "the city too busy to hate." While the city mostly avoided major conflicts, small race riots did happen in 1965 and 1968.

Ending Segregation

Segregation in public places ended in stages. Buses and trolleybuses were desegregated in 1959. Restaurants at Rich's department store desegregated in 1961. Movie theaters desegregated in 1962-63. In 1961, Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. was one of the few Southern white mayors to support desegregating his city's public schools. However, initial changes were small, and full desegregation happened gradually from 1961 to 1973.

1962 Air Crash and Its Impact on Arts

In 1962, Atlanta and its arts community were deeply affected by the deaths of 106 people on Air France charter flight 007. The Atlanta Art Association had sponsored a tour of European art treasures. 106 members of the tour were returning to Atlanta on the flight when it crashed. The group included many of Atlanta's cultural and civic leaders.

The loss was a turning point for the arts in Atlanta. It helped create the Woodruff Arts Center, originally called the Memorial Arts Center, as a tribute to the victims. The French government donated a Rodin sculpture, The Shade, to the High Museum in memory of the victims.

The crash happened during the Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harry Belafonte canceled a sit-in in downtown Atlanta as a gesture of sympathy to the grieving city.

Freeway Construction and Protests

Atlanta's freeway system was completed in the 1950s and 1960s. The Perimeter highway was finished in 1969. Historic neighborhoods were damaged or destroyed by this construction. Other planned freeways were never built due to protests from city residents. The opposition lasted three decades. Then-governor Jimmy Carter played a key role in stopping I-485 through neighborhoods in 1973.

Urban Renewal

In the 1960s, poor areas like Buttermilk Bottom were torn down. The idea was to build better housing. However, much of the land remained empty until the 1980s when new communities were built in what was renamed Bedford Pine. The African-American community east of downtown suffered as the center of the Black economy moved to southwestern Atlanta. During the 1960s, African-American citizens' rights groups emerged to address the lack of housing for poor Black people.

Shoppers Move to Malls, Downtown Changes

The first major mall in Atlanta was Lenox Square in Buckhead, which opened in August 1959. From 1964 to 1973, nine more major malls opened, mostly near the Perimeter freeway. Downtown Atlanta became less of a shopping destination. Rich's closed its main downtown store in 1991. Government offices became the main presence in the South Downtown area.

North of Five Points, Downtown remained the largest area for offices in Metro Atlanta. However, it began to compete with Midtown, Buckhead, and the suburbs. The first four towers of Peachtree Center were built in 1965-1967. This included the Hyatt Regency Atlanta, designed by John Portman, with its 22-story atrium. In total, seventeen buildings taller than fifteen floors were built in the 1960s. The center of Downtown Atlanta moved north from the Five Points area towards Peachtree Center.

Atlanta's convention and hotel facilities also grew greatly. John C. Portman, Jr. designed and opened the AmericasMart in 1958. The Sheraton Atlanta, the city's first convention hotel, was built in the 1960s. The Atlanta Hilton opened in 1971. The Omni Coliseum opened in 1976, as did the Georgia World Congress Center (GWCC). The GWCC expanded many times and helped make Atlanta one of the country's top convention cities.

Black Political Power and Mayor Jackson

In 1960, white people made up 61.7% of the city's population. African Americans became the majority in the city by 1970. They used their new political influence to elect Atlanta's first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973.

During Jackson's first term, much progress was made in improving race relations in Atlanta. Atlanta gained the motto "A City Too Busy to Hate." As mayor, he led the start of several huge public projects. He helped arrange for the rebuilding of the airport's large terminal. This airport was later renamed the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in his honor. He also fought against building freeways through inner-city neighborhoods.

Building the MARTA Rail System

In 1965, a law created the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, or MARTA. MARTA was meant to provide fast public transport for five large metro counties. However, a vote to join the system failed in Cobb County. A 1968 vote to fund MARTA also failed. But in 1971, Fulton and DeKalb Counties approved a 1% sales tax increase to pay for operations. Clayton and Gwinnett counties strongly rejected the tax, fearing more crime.

In 1972, MARTA bought the existing bus company. Construction on the new train system began in 1975. Service started on June 30, 1979, running east-west. The Five Points downtown hub opened later that year. A short north-south line opened in 1981. By 1984, it had been extended. In 1988, the line was extended to a station inside the airport terminal.

Mayor Andrew Young

In 1981, after being encouraged by many people, including Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King Jr.'s widow, Democratic Congressman Andrew Young ran for mayor of Atlanta. He was elected later that year with 55% of the vote, taking over from Maynard Jackson. As mayor, he brought in $70 billion of new private investment.

Young was re-elected as Mayor in 1985 with over 80% of the vote. Atlanta hosted the 1988 Democratic National Convention during Young's time as mayor. He was not allowed to run for a third term due to term limits. He was followed by Maynard Jackson, who returned as mayor from 1990 to 1994.

Olympic and World City: 1990-Present

1996 Summer Olympics

In 1990, the International Olympic Committee chose Atlanta to host the Centennial Olympic Games in 1996 Summer Olympics. After this announcement, Atlanta started several major construction projects. These improved the city's parks, sports facilities, and transportation. Atlanta became the third American city to host the Summer Olympics.

Shirley Franklin's Time as Mayor

Shirley Franklin's run for mayor in 2001 was her first time running for public office. She won, taking over from Mayor Bill Campbell. She faced a huge and unexpected budget problem. Franklin cut the number of government employees and raised taxes to balance the budget quickly.

Franklin made fixing Atlanta's sewer system a main goal. Before her term, Atlanta's sewer system broke federal laws. This caused the city government to face fines. In 2002, Franklin announced "Clean Water Atlanta" to fix the problem and improve the city's sewer system.

She was praised for her efforts to make Atlanta "green." Under Franklin's leadership, Atlanta went from having very few green-certified buildings to one of the highest numbers.

In 2005, TIME Magazine named Franklin one of the five best big-city American mayors. In October of that year, she was included in the U.S. News & World Report "Best Leaders of 2005" issue. With strong public support and business backing, Franklin was reelected Atlanta Mayor in 2005, winning over 90% of the vote.

2008 Tornado

On March 14, 2008, a tornado tore through downtown Atlanta. This was the first tornado in downtown since weather records began in 1880. Many downtown skyscrapers had minor damage. However, two holes were torn into the roof of the Georgia Dome. Catwalks and the scoreboard fell onto the court during a basketball game. The Omni Hotel was badly damaged, along with Centennial Olympic Park and the Georgia World Congress Center.

BeltLine Project

In 2005, the $2.8 billion BeltLine project was approved. Its goals were to turn a disused 22-mile freight railroad loop around the city into a multi-use trail with art. It also aimed to increase the city's park space by 40%.

Gentrification and Population Changes

Since 2000, Atlanta has changed a lot culturally, demographically, and physically. Much of the city's change was driven by young, college-educated professionals. From 2000 to 2009, the area around Downtown Atlanta gained many residents aged 25 to 34 with college degrees.

As gentrification spread, Atlanta's cultural scene grew. The High Museum of Art doubled in size. The Alliance Theatre won a Tony Award. Many art galleries opened in the formerly industrial Westside area.

The Black population in the Atlanta area moved to the suburbs quickly in the 1990s and 2000s. From 2000 to 2010, the city of Atlanta's Black population shrank by over 31,000 people. It dropped from 61.4% to 54.0% of the population. While Black people moved out of the city and DeKalb County, the Black population increased sharply in other parts of Metro Atlanta. During the same period, the proportion of white people in the city's population grew dramatically. Between 2000 and 2010, Atlanta added over 22,000 white residents. By 2009, a white mayoral candidate, Mary Norwood, lost by only 714 votes. This was a historic change from the past belief that Atlanta would always elect a Black mayor.