Memphis riots of 1866 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Memphis Massacre of 1866 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction Era | |||

| Date | May 1–3, 1866 | ||

| Location |

35.1495° N, 90.0490° W |

||

| Caused by | Racial tensions | ||

| Methods | Rioting, looting, armed robbery, arson, pogrom | ||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

|

|||

The Memphis massacre of 1866 was a terrible series of violent events. They happened from May 1 to 3, 1866, in Memphis, Tennessee. This violence was caused by strong racial tensions. These tensions grew after the American Civil War ended. It happened during the early days of the Reconstruction period.

The violence started after a fight. White police officers and black soldiers who had just left the Union Army were involved. After this fight, groups of white residents and police officers attacked black neighborhoods. They also attacked the homes of freed people. They hurt and killed black soldiers and regular citizens. They also stole things and set many buildings on fire.

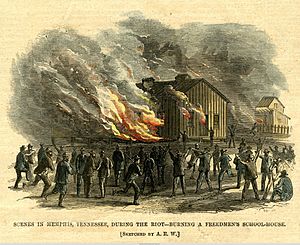

Federal troops were sent in to stop the violence. Peace was finally brought back on the third day. A special report was made by a committee from Congress. It showed how much damage was done. Black people suffered most of the injuries and deaths. 46 black people and 2 white people were killed. 75 black people were hurt. Over 100 black people had their belongings stolen. Also, 91 homes, 4 churches, and 8 schools were burned. All the black churches and schools were destroyed.

Today, experts believe the property losses were over $100,000. Most of this loss was suffered by black people. Many black people left Memphis for good. By 1870, their population in the city had dropped by one-fourth. This was compared to how many lived there in 1865.

News of these riots spread across the country. Another similar event happened in July, called the New Orleans massacre of 1866. These events made Radical Republicans in the U.S. Congress believe more had to be done. They wanted to protect freed people in the Southern United States. They also wanted to give them full rights as citizens. These events helped lead to the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This law gave full citizenship to African Americans. It also influenced the Reconstruction Act. This act set up military control in some states.

Why Did the Memphis Massacre Happen?

Investigations into the riot showed specific reasons for the violence. There was a lot of competition for homes, jobs, and social spaces. This was especially true among working-class people. Irish immigrants and their children competed with freed people for these things.

White plantation owners also wanted black people to leave Memphis. They wanted them to go back to plantations. There, they could work in cotton fields. The violence was a way to try and force back the old social order. This was after slavery had ended with the Emancipation Proclamation.

Memphis After the Civil War

The cotton trade stopped almost completely when the war began. This caused money problems in West Tennessee. In 1862, Union forces took control of Memphis. The city then became a safe place for escaped slaves. These were called "contraband camps." Many enslaved people sought protection there.

In 1860, Shelby County and the four counties nearby had 45,000 enslaved people. As escaped and freed slaves came to Memphis, the black population grew a lot. It went from 3,000 in 1860 to almost 20,000 in 1865. The total population of Memphis in 1860 was 22,623. The arrival of thousands of black people had a big effect. By 1870, the city's total population was 40,226.

Some black people lived in camps. But families of the 3rd Artillery, a black army unit, built their own homes. They settled outside the city limits near Fort Pickering. This area was called South Memphis. Many of their families moved to this same area.

Tennessee was unique because the military stayed there for a long time. During the war, Tennessee created rules that were like "Black Codes." These rules depended on police, lawyers, and judges to enforce them. Slave owners in Tennessee and Memphis faced a shortage of workers. This was because enslaved people were escaping to freedom. They could no longer make money from forced labor. White people were angry and worried about the many freed people in Memphis. They wanted the military to force black people to work. The military sometimes arrested black people called "vagrants." They then forced them to sign work contracts on plantations.

Irish Residents in Memphis

Before the war, many Irish immigrants came to Memphis. In 1850, Irish people made up 9.9 percent of the city's population. By 1860, the population grew quickly to 22,623. Irish people then made up 23.2 percent of the city. They faced a lot of unfair treatment. But by 1860, they held most jobs in the police force. They also won many elected positions in the city government, including mayor.

However, Irish people also competed with free black people for lower-paying jobs. These were jobs that white people often did not want. This caused bad feelings between the two groups. Similar bad feelings between working-class white people (including Irish immigrants) and free black people also caused violence in the North. An example is the 1863 New York City draft riots.

Most Irish immigrants arrived after the Great Famine of the 1840s. Many settled in South Memphis. This was a new neighborhood with many different ethnic groups. South Memphis was mostly home to families of skilled and semi-skilled workers. When the Army took over Memphis, they used nearby Fort Pickering as their main base. The Freedmen's Bureau also set up an office in this area. Black refugees settled further south, outside the city limits.

Growing Tensions in Memphis

Local newspapers like The Daily Avalanche made tensions worse. They wrote articles against black people. They also wrote against the federal government's efforts to rebuild the South after the war. A report by the Freedmen's Bureau after the riot described the long "bitterness" between black people and "low whites." Some recent events had made this anger worse.

In 1866, the mayor and citizens of Memphis told Major General George Stoneman they could keep order. So, General Stoneman reduced his troops at Fort Pickering. He only had about 150 men there. They were used to protect the large amount of military supplies at the fort.

Social tensions in the city grew higher. The U.S. Army used black Union Army soldiers to patrol Memphis. There was also confusion about who was in charge. The military or the local government? After the war, the new Freedmen's Bureau added to this confusion. Through early 1866, there were many threats and fights. These happened between black soldiers and white Memphis policemen. About 90% of the police were Irish immigrants. Many people said that there was a lot of tension between these groups.

Officials from the Freedmen's Bureau reported that police arrested black soldiers for small reasons. They often treated them very badly. This was different from how they treated white suspects. Police were used to treating black people under Tennessee's old slave laws. They did not like seeing armed black men in uniform.

More and more incidents of police brutality happened. In September 1865, Brigadier General John E. Smith banned "public entertainments, balls, and parties" held by black people. Police sometimes violently broke up black gatherings.

The Day Before the Riots

Officers praised black soldiers for staying calm in these situations. But rumors spread among white people. They heard that black people were planning revenge for these incidents. Trouble was expected after most black Union troops were released from the army. This happened on April 30, 1866. The former soldiers had to stay in the city for several days. They were waiting to get their discharge pay. The Army took back their weapons. But some of the men had bought their own guns. They spent their time walking around town and celebrating.

On the afternoon of April 30, a street fight broke out. It was between three black soldiers and four Irish policemen. They insulted each other and then physically clashed. A police officer hit a soldier in the head with a gun. The hit was hard enough to break the officer's weapon. After more fighting, the two groups went their separate ways. News of this incident quickly spread across town.

The Riots Begin

Conflict with Black Soldiers

On May 1, 1866, a large group of black soldiers, women, and children gathered. They were in a public space, having a street party. Around 4 PM, City Recorder John Creighton told four police officers to break up the group. The police did what he said. But the area was outside their normal work area. Also, Creighton was not their direct boss.

Tension grew as the soldiers refused to leave. The four officers were outnumbered. They went back and called for more help. The soldiers chased them, and gunfire started. The conflict got worse. Officer Finn was shot and killed on Avery Street.

Creighton and O'Neill left the scene. They reported that two police officers had been shot. A group of city police and angry white residents gathered. They prepared to fight the black soldiers. Several soldiers were shot and killed early that evening. Some were running away and wounded. One was already under arrest.

General George Stoneman was asked to use military force to stop the violence. He refused. He suggested that Sheriff Winters create a group of citizens to help. This group is called a posse. Stoneman did allow Captain Arthur W. Allyn to send two units of soldiers from Fort Pickering. They patrolled Memphis from about 6 PM until 10 or 11 PM. By then, most of the black soldiers had gone back to their homes. Stoneman also ordered all black soldiers returning to Fort Pickering to give up their weapons. He wanted them to stay on base.

Mob Violence and Destruction

Late in the evening, the white mob found no soldiers. So, they turned to attack black homes in the area. They stole things and attacked the people they found there. They attacked houses, schools, and churches. They burned many of them. They also attacked black residents without caring who they were. Many black people were killed.

These attacks started again on the morning of May 2. They continued for a full day. Police officers and firefighters made up one-third of the mob. Police were 24% and firefighters were 10% of the total group. Small business owners (28%), clerks (10%), skilled workers (10%), and city officials (4.5%) also joined. John Pendergast and his sons Michael and Patrick were said to be key in organizing the violence. They used their grocery store as a base. One black woman said that Pendergast told her, "I am the man that fetched this mob out here, and they will do just what I tell them."

After the first day, General Stoneman said that black people did not act aggressively. They were just trying to survive. At the place where the incident started, City Recorder John Creighton stirred up a white crowd. He told them to get weapons and kill black people. He wanted them driven from the city. Rumors spread that black residents of Memphis were planning an armed rebellion. Local white officials and people who liked to cause trouble spread these rumors. Memphis Mayor John Park was strangely absent. General Runkle, head of the Freedmen's Bureau, did not have enough troops to help.

General George Stoneman was the commander of federal troops in Memphis. He was slow to act in stopping the early stages of the riot. His delay led to more damage. He finally declared martial law on the afternoon of May 3. This meant the military took control. He then used force to bring back order.

Tennessee Attorney General William Wallace was asked to lead a group of 40 men. He was said to have encouraged them to kill and burn.

What Was the Cost?

In total, 46 black people and 2 white people were killed. One white person hurt himself, and the other was likely killed by other white people. 75 people were injured, mostly black people. Over 100 people were robbed. These numbers were given to the congressional hearing committee later. 91 homes were burned. 89 belonged to black people, one to a white person, and one to a mixed-race couple. Four black churches and 12 black schools were also burned. Today, experts believe the property losses were over $100,000. This included money taken from black veterans by the police.

Confederate veteran Ben Dennis was killed on May 3. He was talking with a black friend in a bar.

The results showed that the mob mainly attacked the homes and wives of black soldiers. Setting fires was the most common crime. The mob chose certain homes to attack. They spared others if they thought the people living there were obedient.

Aftermath and Changes

The Daily Avalanche newspaper praised Stoneman for his actions. An editorial said: "He has acted upon the idea that if troops are necessary here to protect the rights of the black people ever, white troops can do this with less offense to our people than black ones. He knows the wants of this country and sees that the negro can do the country more good in the cotton field than in the camp." The Avalanche also believed the violence would bring back the old social order. It wrote: "The chief source of all our trouble being removed, we may confidently expect a restoration of the old order of things. The negro population will now do their duty ... Negro men and negro women are suddenly looking for work on country farms ... Thank heaven, the white race are once more rulers in Memphis."

Investigations and Political Effects

No one was charged or punished for starting or taking part in the Memphis riots. The United States Attorney General, James Speed, said that legal actions for the riots were up to the state. But state and local officials refused to act. No grand jury was ever called.

General Stoneman was criticized for not acting sooner. But a congressional committee investigated him and found him innocent. He said he was slow to act at first. This was because the people of Memphis said they could control themselves. He needed a direct request from the mayor and council. On May 3, they asked for his help to form a posse. He told them no. He then declared martial law. He stopped groups from gathering and ended the riot. Stoneman later moved to California. He was elected governor there, serving from 1883 to 1887.

The Freedmen's Bureau investigated the Memphis riot. The Army and the Tennessee Inspectors General helped. They collected statements from people involved. A Congressional committee also investigated and wrote a report. They arrived in Memphis on May 22. They interviewed 170 witnesses, including Frances Thompson. They gathered many stories from both black and white people.

The Memphis riot and the New Orleans massacre of 1866 in July 1866 had a big effect. They increased support for Radical Reconstruction. Reports of the riot made President Andrew Johnson look bad. He was from Tennessee and had been military governor under Lincoln. Johnson's plan for rebuilding the South was stopped. Congress then moved toward Radical Reconstruction. The Radical Republicans won many seats in the 1866 congressional elections. They gained enough power to overrule the President's vetoes.

After this, they passed important laws. These included the Reconstruction Acts and Enforcement Acts. They also passed the Fourteenth Amendment. This law guaranteed citizenship, equal protection, and fair treatment under the law for former slaves. The change in politics, caused by these riots, helped former slaves gain full citizenship rights.

For the Tennessee Assembly, the riot showed a problem. There were no state laws clearly defining the rights of freed people.

Memphis After the Riots

Many black people left Memphis for good. This was because of the hostile environment. The Freedmen's Bureau kept trying to protect the black residents who stayed. By 1870, the black population had dropped by one-quarter from 1865. It was about 15,000 out of a total city population of over 40,000.

The black community continued to fight for their rights. On May 22, 1866, dock workers at the river went on strike. They marched for higher wages. All the strikers were arrested. Over the summer, a black group called the Sons of Ham held protests. They wanted black people to have the right to vote. They gained this right in the 19th century. But around 1900, Tennessee, like other Southern states, made it hard for black people to register and vote. This kept most black people out of the political system for over sixty years.

The state legislature took control of the city's police force. It passed a law that changed Memphis's criminal punishment system. This law started on July 1, 1886.