Henry McNeal Turner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

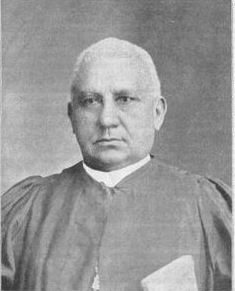

The Right Reverend

Henry McNeal Turner

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the Georgia House of Representatives from the Bibb district |

|

| In office 1868–1869 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 1, 1834 Newberry, South Carolina, United States |

| Died | May 8, 1915 (aged 81) Windsor, Ontario, Dominion of Canada |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Eliza Peacher Martha Elizabeth DeWitt Harriet A. Wayman Laura Pearl Lemon |

| Children | 14 |

| Parents | Hardy Turner Sarah Greer |

Henry McNeal Turner (February 1, 1834 – May 8, 1915) was an important American leader. He was a minister, a politician, and a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). This church was the first independent black church in the United States. It was started by free black people in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the early 1800s.

Turner was born free in South Carolina. He learned to read and write, which was rare for black people at that time. He became a Methodist preacher. In 1858, he joined the AME Church in St. Louis, Missouri. Later, he served as a pastor in Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, D.C..

During the American Civil War, Turner became the first African-American chaplain in the US Army. After the war, he helped former slaves in Georgia through the Freedmen's Bureau. He was elected to the Georgia state legislature in 1868. In 1880, he became the first AME bishop from the Southern United States.

As Jim Crow laws made life harder for black people, Turner began to support black nationalism. He believed black Americans should move to Africa. He was a key figure in this movement in the late 1800s.

Contents

Early Life and Calling

Henry McNeal Turner was born free in 1834. His birthplace was Newberry, South Carolina. His parents were Sarah Greer and Hardy Turner. Both had mixed African and European backgrounds.

His family had an interesting story. His mother's grandfather was brought from Africa as a slave. But slave traders noticed he had royal marks. He was then freed from slavery. This grandfather later worked for a Quaker family.

At that time, South Carolina laws made it illegal to teach black people to read or write. Henry ran away from working in cotton fields. He found a job as a cleaner for a law firm in Abbeville. There, he secretly learned to read and write.

When he was 14, Turner felt called to become a pastor. He got his preacher's license at age 19 in 1853. He traveled the South for several years, sharing his faith.

Moving North and Ministry

In 1858, Turner moved to Saint Louis, Missouri with his family. He worried that his family might be kidnapped and sold into slavery. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it easier to capture black people. It offered little protection for free black individuals.

In St. Louis, Turner became an ordained minister in the AME Church. He studied important subjects like classics, Hebrew, and religion. He served as a pastor in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. In Washington, he met important political leaders.

By 1862, Turner was leading the largest AME church in Washington, D.C. It was close to the government and the war. Many important people came to hear him preach.

Family Life

In 1856, Turner married Eliza Peacher. She was the daughter of a wealthy free black builder. They had 14 children together, but only four lived to adulthood. Eliza passed away in 1889.

Turner married three more times after Eliza's death. He married Martha Elizabeth DeWitt in 1893. After she died, he married Harriet A. Wayman in 1900. She also died a few years later. In 1907, he married Laura Pearl Lemon. He outlived three of his four wives.

Civil War Service

During the American Civil War, Henry McNeal Turner played a brave role. He helped form one of the first black army groups. This group was Company B of the First United States Colored Troops. Turner was made its chaplain, becoming the only black officer in this regiment.

As a chaplain, Turner encouraged black men to join the army. He told them that the future of their race depended on their loyalty. His speeches inspired many.

Turner served as a chaplain for two years. He got sick with smallpox early on. But he recovered and returned to his unit in May 1864. His unit fought in battles around Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia. They also took part in a big attack on Fort Fisher.

After the fighting ended, Turner helped supervise a settlement of freed slaves. He left the army and focused on politics and civil rights. He also worked to spread the AME Church among newly freed people in the South.

Turner wrote many letters from the battlefield. These letters were published in newspapers. They made him well-known across the country. He also helped many former slaves join the AME Church. This church grew greatly after the war.

Political Leadership

After the war, Turner became very active in politics. He joined the Republican Party. He helped start the Georgia Republican Party. In 1868, he was elected to the Georgia Legislature from Macon, Georgia.

However, the Democratic Party controlled the legislature. They refused to let Turner and 26 other black lawmakers take their seats. This group was known as the Original 33. After the US government stepped in, Turner and his colleagues were finally allowed to serve.

In 1869, Turner became the postmaster of Macon. But he was upset when Democrats regained power in the South. They used violence and tricks to stop black people from voting. In 1883, the Supreme Court of the United States made a ruling. It said that a law against racial discrimination in public places was unconstitutional.

Turner was furious about this decision. He said it led to unfair Jim Crow laws. These laws forced black people into separate, worse accommodations. He felt it made black people's right to vote meaningless.

Because of these problems, Turner began to believe in black nationalism. He thought black Americans could only be truly free in Africa. He founded the International Migration Society. He also published newspapers like The Voice of Missions. He organized two ships that took over 500 people to Liberia in 1895 and 1896. However, many returned due to difficulties.

Church Leadership and Legacy

Turner wrote a lot about the Civil War and the lives of black people. He was a correspondent for The Christian Recorder, the AME Church newspaper.

When Turner joined the AME Church in 1858, it had about 20,000 members. Most were in the North. After the Civil War, Turner helped the church grow in the South. He started many new AME churches in Georgia. By 1877, the AME Church had over 250,000 new members. By 1896, it had over 452,000 members nationwide.

In 1880, Turner was elected as the twelfth bishop of the AME Church. He was the first bishop elected from the South. He also supported women's rights and the movement to ban alcohol. He served as chancellor of Morris Brown University, a black college in Atlanta, Georgia.

During the 1890s, Bishop Turner traveled to Liberia and Sierra Leone four times. He organized AME conferences in Africa. He also helped establish the AME Church in South Africa. His efforts helped black African students come to the United States for college.

Turner was known for his powerful speeches. In 1898, he famously preached that God was black. He said that if white people could imagine God as white, black people had the right to imagine God as black. This message was about pride and self-worth for black people.

Henry McNeal Turner died in 1915 while visiting Windsor, Ontario. He was buried in South-View Cemetery in Atlanta. After his death, W.E.B. Du Bois called him one of the "mighty men" who built the African church in America.

Selected Writings

- Introduction to Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising, by Simmons, Cleveland, Ohio, G.M. Rewell & Co., 1887.

- Respect Black; the writings and speeches of Henry McNeal Turner. Compiled and edited by Edwin S. Redkey. New York, Arno Press, 1971.

Legacy and Honors

- Turner Chapel in Oakville, Ontario was named in his honor. It was built in 1890 by former slaves.

- A portrait of Turner hangs in the state capital of Georgia.

- Turner Theological Seminary in Atlanta, Georgia was named after him.

- In 2000, the U.S. Congress named a Macon, Georgia post office in his honor.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Henry McNeal Turner in his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

- Henry McNeal Turner High School in Atlanta, Georgia, is also named for him.

See also

- Methodism

- List of African Methodist Episcopal Churches

- William Gould (W.G.) Raymond

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |