Slaughter-House Cases facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Slaughter-House Cases |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued January 11, 1872 Reargued February 3–5, 1873 Decided April 14, 1873 |

|

| Full case name | The Butchers' Benevolent Association of New Orleans v. The Crescent City Live-Stock Landing and Slaughter-House Company; Paul Esteben, L. Ruch, J. P. Rouede, W. Maylie, S. Firmberg, B. Beaubay, William Fagan, J. D. Broderick, N. Seibel, M. Lannes, J. Gitzinger, J. P. Aycock, D. Verges, The Live-Stock Dealers' and Butchers' Association of New Orleans, and Charles Cavaroc v. The State of Louisiana, ex rel. S. Belden, Attorney-General; The Butchers' Benevolent Association of New Orleans v. The Crescent City Live-Stock Landing and Slaughter-House Company |

| Citations | 83 U.S. 36 (more)

16 Wall. 36; 21 L. Ed. 394; 1872 U.S. LEXIS 1139

|

| Prior history | Error to the Supreme Court of Louisiana |

| Holding | |

| The Fourteenth Amendment only protects the privileges and immunities pertaining to citizenship of the United States, not those that pertain to state citizenship. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Miller, joined by Clifford, Davis, Strong, Hunt |

| Dissent | Field, joined by Chase, Swayne, Bradley |

| Dissent | Swayne |

| Dissent | Bradley |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Art. IV. sec. 2, 13th, 14th, 15th Amendments | |

The Slaughter-House Cases was a very important decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1873. This case was about the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Court decided that a part of this amendment, called the Privileges or Immunities Clause, only protects rights that come from being a U.S. citizen. It does not protect rights that come from being a citizen of a specific state. This decision combined two similar legal cases into one.

The state of Louisiana and the city of New Orleans wanted to make slaughterhouses cleaner. So, they created a company to manage all slaughterhouse work. Butchers from the Butchers' Benevolent Association said this new company was against the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment was added after the American Civil War. Its main goal was to protect the rights of millions of newly freed slaves in the Southern United States. However, the butchers argued that the amendment also protected their right to earn a living through their work.

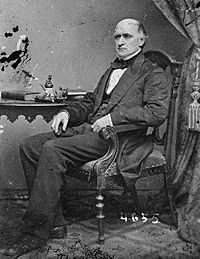

Justice Samuel Freeman Miller wrote the main opinion for the Court. The Court decided that the Fourteenth Amendment had a narrower meaning than the butchers argued. It ruled that the amendment did not stop Louisiana from making rules for public health. This was because the Privileges or Immunities Clause only protected rights given by the United States government, not by individual states. This meant the clause offered very limited protection for only a few rights, like the right to run for federal office.

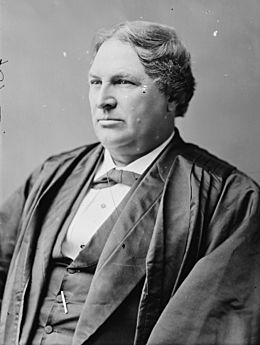

Justice Stephen J. Field disagreed. He wrote that Justice Miller's opinion made the Fourteenth Amendment almost useless. Even though the Slaughter-House Cases reduced the power of the Privileges or Immunities Clause, the Supreme Court later used other parts of the Fourteenth Amendment, like the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause, to challenge state laws.

Contents

What Happened?

About a mile and a half from New Orleans, many butchers worked. They processed over 300,000 animals each year. The waste from these animals polluted New Orleans's drinking water. This pollution was linked to sickness among the people.

To fix this, a group in New Orleans suggested moving the slaughterhouses. But many were outside the city, so the suggestion had no power. The city then asked the state government for help. In 1869, Louisiana passed a law. This law created a company called the Crescent City Live-Stock Landing and Slaughter-House Company. This company would control all slaughterhouse work in the city. Other big cities like New York and San Francisco had similar rules to keep water clean.

The new company, Crescent City, would not slaughter animals itself. Instead, it would rent out space to other butchers for a fee. The law said Crescent City had the "sole and exclusive privilege" to run slaughterhouses in the area for 25 years. All other slaughterhouses had to close. This forced butchers to use Crescent City's facilities. The law also said Crescent City could not favor one butcher over another. All animals at the company's site would be checked by a state official.

More than 400 butchers formed a group to sue. They wanted to stop Crescent City from taking over their business. Justice Samuel Freeman Miller later explained the butchers' worries. They felt the law created a monopoly. This gave special rights to a few people. It also stopped many butchers from doing their job. This job was how they supported their families. They argued that butchering was needed for the city's food supply.

Lower courts had sided with Crescent City in all the cases. Six cases then went to the Supreme Court. The butchers based their arguments on the due process, privileges or immunities, and equal protection parts of the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment had been approved five years earlier. It was meant to protect the rights of newly freed slaves in the South.

The butchers' lawyer was John Archibald Campbell. He had been a Supreme Court Justice but left because of his support for the Confederacy. He used the Fourteenth Amendment's broad language to argue for the butchers. He said it protected the right of all people, no matter their race, to "sustain their lives through labor."

The Court's Decision

On April 14, 1873, the Supreme Court made its decision. Five justices voted for the slaughterhouse company, and four voted against it. The Court said Louisiana had the right to make rules for butchers to protect public health.

Majority Opinion

Justice Samuel Freeman Miller wrote the main opinion for the five justices who agreed. Miller said that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments were mainly created to protect former black slaves. He wrote that the main goal of these amendments was to free slaves and protect them from unfair treatment.

Because of this view, the Court gave a very narrow meaning to the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. First, the Court rejected the butchers' argument about equal protection. It doubted that the Equal Protection Clause would stop anything other than state laws that treated black people unfairly. Next, the Court rejected the butchers' argument about due process. It said that the state's rules on butchers' work were not taking away their property.

The Court then looked at the Privileges or Immunities Clause. It also gave this clause a narrow meaning. The Court said this clause was not meant to protect people from state government actions. It was not meant to be a way for courts to strike down state laws.

The Court believed that if they allowed a broad meaning, they would become "a perpetual censor" over all state laws about citizens' rights. They felt that Congress and the states did not intend this when they created the amendments.

So, the Court ruled that the Privileges or Immunities Clause only protects rights related to being a U.S. citizen. It does not protect the broader rights people have as citizens of their individual states. Miller said these state rights included "nearly every civil right" that governments are created to protect.

Miller explained that the Fourteenth Amendment's Citizenship Clause gave national U.S. citizenship to freed black slaves. This changed the Court's earlier decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Miller said that an older part of the Constitution (Article IV) protected broad state rights. But he argued that the Fourteenth Amendment's language was different. He said it only spoke of rights for "citizens of the United States," not citizens of the states. He concluded that states had power over their citizens' rights, not the federal government.

Miller did not list all the rights of federal citizenship. But he mentioned some, like the right to ask U.S. Congress for help, the right to vote in federal elections, and the right to travel and trade between states. He said the butchers' claimed rights were not federal citizenship rights.

Dissenting Opinions

Four justices disagreed with the Court's decision. Three of them wrote their own opinions explaining why.

Justice Stephen J. Field argued that Miller's narrow reading made the Fourteenth Amendment "a vain and idle enactment." This meant it became a useless law that caused a lot of excitement for no reason. Field believed the amendment protected more than just freed slaves. He thought it protected a person's right to have a lawful job. Field's ideas about the due process clause later became important in future cases.

Justice Joseph P. Bradley also disagreed with how the Court understood the Privileges or Immunities Clause. He listed many rights from the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. These included rights like trial by jury, freedom of religion, and protection from unfair searches. Bradley said these were rights of U.S. citizens, or even stronger, rights of all people.

Justice Noah H. Swayne criticized the Court for saying the Fourteenth Amendment was not meant to change American government much. He said that Congress and the states knew the power it would give. Swayne believed the government needed this power to protect everyone's rights. He said that without such power, any government claiming to be national would be very weak.

What Happened Next?

The Crescent City Company's special privilege lasted only 11 years. By 1879, Louisiana had a new constitution. This new constitution stopped the state from giving out monopolies for slaughterhouses. It gave control of slaughterhouse rules to local areas. It also banned local governments from giving special monopoly rights.

Crescent City Company sued because it lost its monopoly. But in 1884, the Supreme Court decided in Butchers' Union Co. v. Crescent City Co. The Court ruled that Crescent City Company did not have a contract with the state. So, taking away its monopoly was not against the Contract Clause.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |