Absalom Jones facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Absalom Jones

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 7, 1746 |

| Died | February 13, 1818 (aged 71) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

|

| Occupation | Clergyman (Anglican/Episcopal Church) |

| Known for | Anti-slavery petitioner |

| Spouse(s) | Mary King |

| Relatives | Julian Abele (architect) |

Absalom Jones (November 7, 1746 – February 13, 1818) was an important African-American leader. He fought against slavery and became a clergyman. He lived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Jones faced unfair treatment because of his race in a local Methodist church. This led him to start the Free African Society in 1787 with Richard Allen. This group was a "mutual aid society," meaning it helped African Americans in the city. Many people in this society had recently gained their freedom after the American Revolutionary War.

In 1794, Jones started the first black Episcopal church. Then, in 1802, he made history. He became the first African American to be officially made a priest in the Episcopal Church in the United States. The Episcopal Church honors him as a saint. They remember him every year on February 13, the day he died.

Contents

Early Life and Freedom

Absalom Jones was born into slavery in Sussex County, Delaware, in 1746. When he was 16, his owner sold him. His mother and siblings were also sold. Absalom was taken to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where his new owner became a merchant.

Absalom was lucky because he was allowed to go to Benezet's School. There, he learned how to read and write. While he was still enslaved, Absalom married Mary King on January 4, 1770. She was also enslaved by a neighbor.

By 1778, Absalom worked hard to buy his wife's freedom. He wanted their children to be born free. At that time, children born to enslaved mothers were also born enslaved. Absalom also asked his owner for his own freedom. At first, he was told no. But in 1784, his owner, Mr. Wynkoop, finally freed him. This was partly because of the new ideas about freedom from the American Revolution. Absalom chose the last name "Jones" to show he was an American.

Starting the Methodist Church

Around 1780, a new religious movement called Methodism became popular. It was part of the Second Great Awakening. This was happening during the end of the American Revolutionary War. Methodism grew quickly in cities like New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

Methodists were a group that came from the Church of England. In December 1784, the Methodist Episcopal Church became its own separate church.

Ministerial Career

Pennsylvania became a free state, meaning slavery was against the law there. Absalom Jones became a lay minister at St. George's Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. This church allowed people of all races to join. It also let African Americans preach. Jones and Richard Allen were among the first African Americans allowed to preach by the Methodist Church.

However, even in this church, there was still racial unfairness. In 1792, Absalom Jones and other African American members were told they could not sit with the white members. They had to sit separately, first against the wall, and then in the balcony. After they finished their prayer, Jones and most of the African American members walked out of the church.

Jones and Allen then started the Free African Society (FAS). It was a group meant to help newly freed people in Philadelphia. Jones and Allen later went in different religious directions. But they stayed friends and worked together throughout their lives.

In 1791, Jones began holding religious services at the Free African Society. This group soon became the start of his own African Church in Philadelphia. Jones wanted to create an African American church that was independent. But he still wanted it to be part of the Episcopal Church. After asking for permission, the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas opened on July 17, 1794. This was the first black church in Philadelphia. Jones was made a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802. This made him the first African American priest in the Episcopal Church.

Jones was known for his powerful speeches. He helped start a tradition of giving anti-slavery sermons on New Year's Day. His sermon on January 1, 1808, was very famous. This was the day the U.S. Constitution said the African slave trade had to end. People said Jones had a special way of influencing his listeners.

Fighting for Freedom: The Fugitive Slave Act

In 1775, North Carolina made it hard to free enslaved people. But some groups, like the Quakers, kept freeing their slaves. They even bought enslaved people just to set them free. In 1788, North Carolina passed a law. It said that if a formerly enslaved person had been freed without court approval, they could be captured and sold back into slavery. Many free African Americans left the state to avoid this.

After becoming the first black priest, Jones continued to fight for freedom. He was part of the first group of African Americans to ask the U.S. Congress for help. They spoke out against the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. This law allowed slave owners to reclaim enslaved people who had escaped to free states. Jones and others said the law was cruel. They also said it encouraged the kidnapping of free black people to sell them into slavery.

Jones wrote a petition for four formerly enslaved people. He asked Congress to find a solution to this big problem. The petition was presented on January 30, 1797. Jones tried to convince white leaders that slavery was wrong and against God's will. Even though some in Congress supported the petition, the House of Representatives voted against accepting it. Jones sent a similar petition two years later, but it was also turned down.

Richard Allen and the AME Church

At the same time, Richard Allen (bishop) (1760–1831) was also building a new church. He founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). This was the first independent black church in the Methodist tradition. Allen and his followers opened their church, Bethel AME Church, on July 29, 1794.

In 1799, Allen became the first black minister in the Methodist Church. In 1816, Allen brought other black churches together. They formed a new, fully independent church group called the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Allen was chosen as the AME's first bishop in 1816.

Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

In the 1790s, Yellow fever hit Philadelphia and other cities many times. During one serious outbreak in 1793, many white people, including most doctors, left the city. They hoped to avoid getting sick.

Absalom Jones and Richard Allen stepped up to help. They organized a group of African American Philadelphians. This group helped care for the sick and bury the dead. Jones worked tirelessly, sometimes all through the night.

Later, a writer named Mathew Carey published a pamphlet. It wrongly accused African Americans of charging too much to care for sick white citizens. Jones and Allen wrote their own pamphlet to respond. They explained the great sacrifices they and the Free African Society made to help the city. The Mayor of Philadelphia, Matthew Clarkson, publicly thanked Jones and Allen. He said they helped the whole community. Jones's actions during this crisis helped build stronger connections between free African Americans and many white citizens. This support was very helpful when he later started St. Thomas' Episcopal Church.

Death and Legacy

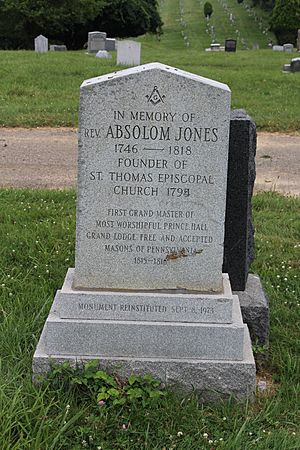

Absalom Jones died on February 13, 1818, in Philadelphia. He was first buried at St. Thomas Churchyard. Later, his body was moved to Lebanon Cemetery and then to Eden Cemetery.

In 1991, his remains were moved again. They were placed in a special container inside the Absalom Jones altar at the current African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. A chapel and the church's rectory (the priest's house) are named in his honor. A cenotaph (a monument for someone buried elsewhere) was placed at Eden Cemetery where he was once buried.

The national Episcopal Church remembers Absalom Jones every year. They celebrate his life and service on February 13, the day he died. The Diocese of Pennsylvania also honors him with an annual celebration and award.

See also

- List of slaves