Slavery in Haiti facts for kids

Slavery in Haiti started when Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492. European settlers from Portugal, Spain, and France followed, bringing the practice of slavery with them. This was terrible for the native people. After most of the native Taíno people died from forced labor, sickness, and war, the Spanish started bringing enslaved Africans to the island in the 1600s. This was done with advice from a Catholic priest, Bartolomé de las Casas, and the church's blessing.

During the French colonial period, which began in 1625, the economy of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) relied completely on slavery. The conditions for enslaved people in Saint-Domingue were known to be extremely harsh, even compared to other places where slavery existed.

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1803) was the only successful slave rebellion in history. It led to the end of slavery not just in Saint-Domingue, but in all French colonies. This revolution also inspired independence movements in Latin America. However, after the revolution, some Haitian leaders still used forced labor. They believed a plantation-style economy was the only way for Haiti to succeed. They also built forts to protect against French attacks. Later, during the U.S. occupation (1915-1934), the U.S. military forced Haitians to build roads for defense against Haitian fighters.

Even today, unpaid labor happens in Haiti. About half a million children are unpaid domestic servants called restavek. Also, human trafficking, including child trafficking, is a big problem. People are brought into, out of, and through Haiti for forced labor. The people most at risk are the poor, women, children, the homeless, and those crossing the border with the Dominican Republic.

The terrible 2010 Haiti earthquake made many people homeless and vulnerable to traffickers. The chaos after the earthquake also made it harder for authorities to stop trafficking. The Haitian government has tried to prevent trafficking by signing human rights agreements and making laws. But it's still hard to make sure these laws are followed. In 2017, the U.S. State Department placed Haiti on a "Tier 2 Watchlist" for its efforts against trafficking.

Contents

Haiti's History with Slavery

Early Spanish Rule (1492–1625)

When Christopher Columbus and his crew arrived on the island of Hispaniola in October 1492, the native people welcomed them. Before Columbus, some other Caribbean tribes would sometimes raid the island to take people as slaves. But after Columbus, European colonists made slavery a huge business. They quickly started large sugar farms that needed many enslaved workers.

When Columbus arrived in what is now Haiti in December 1492, he met the native Taíno Arawak people. They were friendly and exchanged gifts with the Spanish. Columbus wrote to Queen Isabella of Spain that the natives were "easy to manage, and easily led." He thought they could be made to grow crops and build cities.

When Columbus went back to Europe in 1493, 30 Spaniards stayed to build a fort called La Navidad. These Spaniards started stealing from and enslaving the natives. Finding gold was a main goal for the Spanish. They quickly forced enslaved natives to work in gold mines. This work was very hard and many died. Besides gold, slaves also mined copper and grew crops for the Spanish.

The natives fought back against this harsh treatment. Some Taíno escaped into the mountains and formed hidden communities called "maroons." These groups organized attacks against Spanish settlements. The Spanish responded with harsh punishments. For example, they destroyed crops to starve the natives. They also brought dogs trained to kill natives who rebelled. In 1495, the Spanish sent 500 captured natives to Spain as slaves. But 200 died on the trip, and the others died soon after.

We don't know exactly how many Taíno people lived on the island before Columbus. Estimates range from a few thousand to eight million. But overwork from slavery and diseases brought by Europeans quickly killed many of them. Between 1492 and 1494, one-third of the native population died. Within ten years of the Spanish arrival, two million had been killed. By 1514, 92% of the native population had died from slavery and European diseases. By the 1540s, the native culture had almost disappeared from the island. By 1548, fewer than 500 native people were left.

Because so many native slaves died quickly, the Spanish had to bring in Africans. Africans had already been in contact with Europeans, so they had some immunity to European diseases. Columbus's son, Diego Columbus, started the African slave trade to the island in 1505. Some new slaves from Africa and nearby islands managed to escape and join the maroon communities in the mountains. In 1519, Africans and Native Americans joined together to start a slave rebellion. This uprising lasted for years but was eventually stopped by the Spanish in the 1530s.

A Spanish missionary named Bartolomé de las Casas spoke out against the enslavement of natives and the cruelty of the Spanish. He wrote that for the natives, the Christianity brought by the Spanish came to mean the harsh way they were treated. He quoted a Taíno chief who said, "They tell us, these tyrants, that they adore a God of peace and equality, and yet they take our land and make us their slaves."

Las Casas's efforts led to an official end to the enslavement of Taínos in 1542. However, this was replaced by the African slave trade. As Las Casas had warned, the Spanish treatment of the Taínos was the beginning of a long history of slavery.

French Rule in Saint-Domingue (1625–1789)

In 1697, the Spanish gave control of the western part of Hispaniola to the French in the Treaty of Ryswick. France named its new colony Saint-Domingue. This colony, which grew crops like sugar cane for export, became the richest in the world. It was known as the "Pearl of the Antilles" and was the world's top producer of coffee and sugar.

Like the Spanish, the French brought many slaves from Africa. In 1681, there were only 2,000 slaves in Saint-Domingue. By 1789, this number had grown to almost half a million.

The French in Saint-Domingue had a strict class system for both white people and free people of color. The highest class, called grands blancs (white noblemen), were rich nobles, including royalty. They mostly lived in France and held most of the power and land in Saint-Domingue.

Below them were the petits blancs (white commoners) and the gens de couleur libres (free people of color). These groups lived in Saint-Domingue and had a lot of local political power. Petits blancs and gens de couleur libres were on a similar social level.

The gens de couleur libres included affranchis (former slaves), free Black people, and mixed-race people. They owned a lot of wealth and land, similar to the petits blancs. They had full citizenship rights. However, over time, the royal government started policies that caused racism and segregation against them. This was because the government feared the combined power of all St. Dominicans.

Some sugar plantation owners worked their slaves very hard. Starting a sugar cane plantation was very expensive, often putting owners deep in debt. Many enslaved people on sugar cane plantations died within a few years. It was cheaper to buy new slaves than to make working conditions better. The death rate for enslaved people on Saint-Domingue's sugar cane plantations was higher than anywhere else. Slaves working on sugar plantations had a 6-10% death rate each year. This meant Saint-Domingue sugar planters had to buy new slaves often.

Over the colony's 100-year history, about a million enslaved people died due to the harsh conditions. On some sugar plantations, there wasn't enough food. Enslaved people were expected to grow and prepare their own food, on top of working 12-hour days.

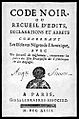

In 1685, the French king Louis XIV created the Code Noir. This was a law meant to control how enslaved people were treated. It was supposed to protect their rights. But because Saint-Domingue had difficult terrain and plantations were isolated, some enslaved people were still abused. On some plantations, enslaved people caught eating sugar cane were forced to wear tin muzzles in the fields.

About 48,000 enslaved people in Saint-Domingue escaped from their plantations. Slave owners hired bounty hunters to catch these maroons. Those who were not caught formed communities away from settled areas. Maroons would raid plantations to steal food, tools, and weapons. A famous maroon, François Mackandal, escaped into the mountains in the mid-1700s. He planned attacks on plantation owners. Mackandal was caught and killed in 1758, but his story inspired other enslaved people to rebel. It also made slave owners afraid.

Enslaved Africans who ran away to remote mountains were called marron (French) or mawon (Haitian Creole), meaning 'escaped slave'. These maroons formed strong communities. They grew small amounts of food and hunted. They were known to return to plantations to free family and friends. Sometimes, they even joined the Taíno settlements that had escaped the Spanish.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, many maroons lived in the Bahoruco mountains. French expeditions tried to catch them but had limited success. The maroons continued to attract runaways. In 1782, a French official offered peace to a maroon leader named Santiago. He offered them freedom if they would hunt other runaways and return them. By 1785, an agreement was reached. The more than 100 maroons under Santiago's command stopped raiding French areas.

Besides escaping, enslaved people resisted by poisoning slave owners, their families, and their animals. This was so common and feared that in 1746, the French king specifically banned poisoning. Setting fires was another way enslaved people resisted.

In 1791, St. Dominican Creoles started the French Revolution in Saint-Domingue. Republican revolutionaries encouraged a slave rebellion to overthrow the old government. Their main goal was to gain control of Saint-Domingue and ensure equal rights for St. Dominican Creoles. However, these St. Dominican Republicans soon lost control of the slave rebellion.

Many enslaved people who fought in the Haitian Revolution were warriors who had been captured in wars in Africa. Before the French Revolution began in 1789, there were eight times more enslaved people in the colony than white people and free people of color combined. In 1789, the French were bringing in 30,000 enslaved people a year. There were half a million enslaved people in the French part of the island alone. This was compared to about 40,000-45,000 white people and 32,000 free people of color.

The Revolutionary Period (1789–1804)

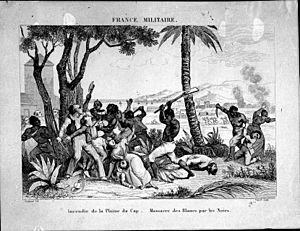

The French Revolution in 1789 gave the middle class of Saint-Domingue a chance to start a revolt. Soon after, they encouraged a general slave revolt. In 1791, enslaved people rebelled, killing white people and burning plantations.

Two French officials, Sonthonax and Polverel, were sent to the colony. Their job was to put into practice a law from April 4, 1792. This law gave free people of color and free Black people the same rights as white people. Their other goal was to keep slavery and fight the rebellious enslaved people. But they couldn't stop the revolt. Also, they faced attacks from the Spanish and English. To keep Saint-Domingue for France, they had to offer freedom to enslaved people who would fight with them. Then, they extended this freedom to all enslaved people in the colony.

By February 1794, when the French government officially ended slavery throughout its empire, all enslaved people in Saint-Domingue were already free.

Even though slavery was outlawed, Toussaint Louverture believed that the plantation economy was necessary. He used military force to make laborers go back to work on the plantations. By 1801, the revolt had succeeded. Louverture had taken control and removed all opposition on the island. He declared himself Governor-General-for-life of Saint-Domingue.

To bring back slavery, Napoleon Bonaparte sent his brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc, to take back control of Haiti. He came with 86 ships and 22,000 soldiers. The Haitians fought back, but the French had more soldiers. Then, the rainy season brought yellow fever. As French soldiers and officers died, Black Haitian soldiers who had joined the French switched sides.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines' Rule

In 1802, Louverture was arrested and sent to prison in France, where he later died. Jean-Jacques Dessalines took over leadership of the military. In 1804, the French were defeated. France officially gave up control of Haiti. This made Haiti the second independent country in the Americas (after the U.S.). It was also the first successful slave revolt in the world. Dessalines became the country's leader, first calling himself Governor-General-for-life, then Emperor of Haiti.

After the revolution, newly freed enslaved people strongly did not want to stay on plantations. But Dessalines, like Louverture, used military force to keep them there. He thought plantation work was the only way to make the economy work. Most former enslaved people saw Dessalines' rule as just another form of the oppression they had known. Dessalines was killed by a group of his own officers in 1806.

Henri Christophe's Leadership

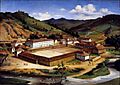

Dessalines' successor was King Henry Christophe, another general from the revolution. Christophe feared another French invasion. He continued to strengthen the country, just like Dessalines. For example, he forced hundreds of thousands of people to work on building a huge fortress called La Citadelle Laferrière. It's believed that about 20,000 people died during its construction.

Like Louverture and Dessalines, Christophe used military force to make former enslaved people stay on the plantations. However, plantation workers under Louverture and Christophe were paid. They received one-quarter of what they produced, with the rest going to plantation owners and the government. Under Christophe's rule, Black people could also rent their own land or work for the government. Farm workers on plantations could even complain to the royal government about working conditions. These former enslaved people might have sometimes had a choice about which plantation to work on. But they could not choose not to work, and they couldn't legally leave a plantation they were "attached" to. Many were probably forced to work on the same plantations where they had been enslaved.

The people strongly resisted working on plantations, whether owned by white people or others. This made it too hard to keep the system going, even though it was profitable. Christophe and other leaders allowed state land to be divided and sold to citizens. The plantation system largely changed to one where Haitians owned and farmed smaller plots of land.

Jean-Pierre Boyer and Debt

In 1817, a Haitian ship captured a Spanish slave ship headed for Cuba that had entered Haiti's waters. Following government orders, the ship was brought ashore. All 171 captive Africans were freed and welcomed into Haitian society. President Jean-Pierre Boyer himself became their godfather. The ship's captain and later Cuban officials argued that their trade was legal. But Boyer insisted that Haiti's 1816 constitution said there could be no slaves in Haitian territory. So, no money would be paid for their value. Slave ships had also been seized and their human cargo freed under previous leaders like Christophe and Alexandre Pétion. Enslaved people who managed to take control of ships and reach Haiti were given safety. Slave traders quickly learned to avoid Haiti's waters.

In 1825, France sent a large fleet of ships to Haiti. They threatened to block trade unless Boyer agreed to pay France 150,000,000 francs. This money was to pay France for the "property" they lost, mostly their enslaved people. In return, France would recognize Haiti as an independent nation, which they had refused to do until then. Boyer agreed without telling the public first, which caused widespread anger in Haiti. The amount was later reduced to 90,000,000 francs in 1838. This was equal to about USD $19 billion in 2015. Haiti was stuck with this debt until 1947. This meant they couldn't spend money on important things like sanitation. In 1838, about 30% of the country's yearly budget went to debt. By 1900, this had risen to 80%. Haiti had to take out loans from Germany, the U.S., and France itself to pay this money. This made their debt even bigger and gave these countries more control over Haiti's economy.

To get money for the debt, Boyer created new laws in 1826 called the Code Rural. These laws limited the freedom of farm workers. They had to work and couldn't travel without permission. It also brought back the Corvée system. This meant police and government officials could force people to work temporarily without pay on roads. These laws were very unpopular and hard to enforce. Workers could hide from the government because they had access to their own land.

The United States passed laws to keep Haitian merchants away from U.S. soil. Slave owners in the U.S. didn't want their slaves to get ideas about rebellion from Haitians. However, the two countries continued to trade. Haiti bought weapons, though at bad prices. The U.S. ban on trade with Haiti lasted 60 years. But President Lincoln later said it was not necessary to deny Haiti's independence once slavery in the United States began to end. He encouraged newly freed slaves to move to Haiti to find a freedom he didn't think was possible in the U.S.

Forced Labor During U.S. Occupation (1915-1934)

In July 1915, after political unrest and the killing of Haiti's president, the United States Marine Corps invaded Haiti. Before the occupation, farmers had rebelled against U.S. investors who wanted to take their land. These investors wanted to change farming back to a plantation-like system. Haitians strongly resisted going back to anything like plantations. Rural Haitians formed groups that roamed the countryside, stealing from farmers. The U.S. occupied Haiti partly to protect investments and to stop European countries from gaining too much power there. One reason given for the occupation was to end the practice of enslaving children as domestic servants. However, the United States then brought back the corvée system of forced labor.

Like under Dessalines and Christophe, unfree labor was used again for public works. This time, it was ordered by U.S. Admiral William Banks Caperton. From 1916 to 1918, the U.S. occupiers used the corvée system. This system was allowed by Haiti's 1864 Code Rural. Haitian resistance fighters, called Cacos, hid in remote mountains and fought the Marines using guerrilla tactics. The military needed roads to find and fight them. To build these roads, laborers were forced from their homes and tied together in chain gangs. Peasants were told they would be paid and given food, working near their homes. But sometimes the promised food and wages were very little or didn't come at all. Corvée was very unpopular. Haitians widely believed that white people had returned to Haiti to force them back into slavery. The harshness of the forced labor system made the Cacos stronger. Many Haitians escaped to the mountains to join them, and many more helped them. Reports of the abuses led the Marine commander to order an end to the practice in 1918. However, it continued illegally in the north until it was discovered. No one was punished for this. With corvée no longer available, the U.S. turned to prison labor. Men were sometimes arrested just to be used for this work if there weren't enough prisoners. The occupation lasted until 1934.

Reparations for Slavery

Reparations for slavery means giving something to victims of slavery or their descendants to make up for the harm done. In Haiti, this hasn't happened. Instead, Haiti paid France for over 120 years to get "formal recognition" of its freedom from France.

Haiti's Demand for Repayment

In 2004, the Haitian government demanded that France repay Haiti. This was for the millions of dollars Haiti paid between 1825 and 1947. This money was compensation to French slave owners and landowners for their "property" losses when enslaved people became free.

Slavery Today

Even though slavery has been banned for more than a century, many criminal groups still practice human trafficking and the slave trade.

Slavery is still common in Haiti today. According to the 2014 Global Slavery Index, about 237,700 people in Haiti are enslaved. This makes Haiti the country with the second-highest number of enslaved people in the world, after Mauritania.

Haiti has more human trafficking than any other country in Central or South America. The United States Department of State's 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report said that "Haiti is a major source, passage, and destination country for men, women, and children subjected to forced labor."

Haitians are trafficked out of Haiti to the nearby Dominican Republic. They are also sent to other countries like Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil, and North American countries. Haiti is also a country that traffickers use to move victims on their way to the United States. After the 2010 Haiti earthquake, human trafficking greatly increased. While trafficking often means moving people across borders, it also includes "the use of force, fraud, or coercion to exploit a person for profit." It is a form of slavery.

Because of this, both parts of the Haitian Parliament, the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, are working hard to end slavery and human trafficking.

Children and the Restavek System

Child trafficking is a big part of the human trafficking problem in Haiti. One major type of child trafficking and child slavery affects an estimated 300,000 Haitian children. It's called the restavek system. In this system, children are forced to work as domestic servants.

The restavek system makes up most of the human trafficking in Haiti.

Families send their children to live in other households. The children work in exchange for being raised. Poor parents in rural areas hope their children will get an education and a better life in the city. So, they send them to wealthier (or less poor) households. More and more, children become domestic servants when a parent dies. Paid middlemen might find the children for the host families. Unlike traditional slaves, restaveks are not bought or sold or owned. They can run away or return to their families. They are usually freed from service when they become adults. However, the restavek system is generally understood to be a form of slavery.

Some restaveks do get enough food and an education, but they are a small group. Restaveks' work includes carrying water and wood, buying groceries, doing laundry, cleaning houses, and taking care of other children. Restaveks work long hours (often 10 to 14 a day) in harsh conditions. They are often not allowed to go to school and are at high risk of not getting enough food. Those who are kicked out or run away become street children. Those who return to their families might not be welcome because they are an extra financial burden. They might also feel ashamed or be looked down upon for having been a restavek. The pain of abuse and not having free time or a normal childhood can hurt a child's development and have long-lasting effects.

The word restavek comes from the French phrase "to live with," rester avec. This practice has existed since the end of the revolution but became common in the 1900s. It was a way for poor rural people to cope with poverty. The number of restaveks increased after the 2010 earthquake. Many children became orphans or were separated from their families then. In 2013, the U.S. Department of State estimated that between 150,000 and 500,000 children were in domestic servitude. This accounts for most of Haiti's human trafficking. About 19% of Haitian children aged 5 to 17 live away from their parents. About 8.2% are considered domestic workers. It is estimated that another 3,000 Haitian children are domestic servants in the Dominican Republic.

Children are also trafficked out of Haiti by groups claiming to be adoption agencies. They are taken to countries like the U.S. But some are actually kidnapped from their families. This happened a lot in the chaos after the 2010 earthquake. International concern grew when, on January 29, 2010, ten members of the American New Life Children's Refuge were arrested. They were trying to take 33 Haitian children out of the country to an orphanage. But the children were not orphans. Traffickers pretending to be from charities have tricked refugee families. They convince them that their children will be safe and cared for. Sometimes, traffickers run "orphanages" that are hard to tell apart from real organizations. Children might be smuggled across the border by paid traffickers pretending to be their parents. Then, they are forced to work for begging groups or as servants. Child trafficking led UNICEF to fund the Brigade de Protection des Mineurs. This is a part of the national police that watches for child trafficking at borders and refugee camps.

The Haitian–Dominican Border

For many years, Haitians have crossed the Haitian-Dominican border for different reasons. These include moving willingly or unwillingly, living there for long or short times, entering legally or illegally, and being smuggled or trafficked. Haitians cross the border looking for opportunities, but they are very vulnerable to being exploited. The Dominican Republic has one of the worst records for human rights abuses, including human trafficking, against migrant workers in the Caribbean. Haitians in the Dominican Republic are often looked down upon as a minority group because the countries are so close. During the rule of Jean-Claude Duvalier in the 1970s and 80s, he sold Haitians in large numbers to work on sugar plantations in the Dominican Republic.

Most people who cross the border are women and girls. The movement of Haitian women to the Dominican Republic is linked to changes in labor markets. It's also due to the difficult situation of women and their families in Haiti. Women migrants are especially at risk of human trafficking, violence, and illegal smuggling. When trying to cross the border, Haitian women risk being robbed, attacked, and killed. This can happen at the hands of smugglers, criminals, and traffickers, both Dominican and Haitian. Because of this danger, women use unofficial routes and rely on hired buscones (informal guides), cousins, and other distant family to help them cross. These hired smugglers, who promised to help, often use force and trick them. Instead, they force them into domestic labor in private homes in Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. Often, mothers need their young children to help support the family. This puts the children in vulnerable situations and allows them to become victims of predators and traffickers. The number of children smuggled into the Dominican Republic is unknown. But UNICEF estimated the number was 2,000 in 2009 alone.

Government Efforts

| HAITI | Ratified |

|---|---|

| Forced Labour Convention | Yes |

| Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery | Yes |

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights | Yes |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child | Yes |

| Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention | Yes |

| UN Trafficking Protocol | No |

| Domestic Work Convention | No |

The 2014 U.S. Trafficking in Persons Report placed Haiti on the Tier 2 Watch List. This means Haiti's government doesn't fully meet the minimum standards of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act. But it is making big efforts to meet those standards. Also, the number of victims of severe trafficking is very high or growing fast. Some of Haiti's efforts to fight modern slavery include signing several important agreements. These include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention Concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor. They also signed the ILO Minimum Age Convention. If these agreements are followed, they could help fight human trafficking. In 2000, Haiti signed the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, but they haven't officially approved it yet. Haiti has also not approved the Convention on Domestic Workers.

Fighting the Restavek System

Haitian law forbids abuse, violence, exploitation, and servitude of children. This is in line with international agreements. It says that all children have the right to an education and to be free from cruel and inhuman treatment. In 2003, Article 335 of the Haitian Labor code banned hiring children under 15. Also, a law passed in June 2003 specifically outlawed placing children into restavek service. The law states that a child in domestic service must be treated the same as the family's own children. However, it doesn't have criminal punishments for those who break these rules. Despite these laws, the practice of restavek continues and grows. Political problems and a lack of money make it hard to stop child trafficking.

Law Enforcement and Help for Victims

The government has tried to address the issue of trafficking women and children legally. They sent a bill to Parliament because they had approved the Palermo Protocol, which required it. In 2014, law CL/2014-0010 was passed. This law made trafficking a crime with penalties of up to 15 years in prison. However, it's still hard to enforce. Things that make it difficult to fight human trafficking include widespread corruption. Also, there's a lack of quick action on cases that show signs of trafficking. The judicial branch is slow to solve criminal cases, and government agencies don't have enough money.

People made homeless by the 2010 earthquake are at a higher risk of forced labor. International protections for internally displaced persons (people displaced within their own country) don't apply to earthquake survivors who have crossed an international border. There's nothing protecting those displaced outside their country. This leaves big gaps in protection for the most vulnerable, like girls and young women. They are treated as illegal migrants instead of forced migrants who need help. No temporary protected status has been given in the Dominican Republic.

Since the 2010 Haiti earthquake, international aid and local efforts have focused on relief and recovery. As a result, few resources have been set aside to fight modern slavery. There are no government-run shelters to help human trafficking victims. The government sends victims to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for services like food and medical care. Most help for victims comes from Haitian NGOs. These include Foyer l'Escale, Centre d'Action pour le Developpement, and Organisation des Jeunes Filles en Action. They provide housing, education, and psychological support to victims. Also, the IOM has been working with local NGOs and the Haitian Ministry of Social Affairs. They also work with the Institute for Social Welfare and Research or the Brigade for the Protection of Minors of the Haitian national police to deal with human trafficking.

Prevention Efforts

The government has tried to prevent and reduce human trafficking. In June 2012, the IBESR (Institut du BienEtre Social et de Recherches) started a human trafficking hotline. They also ran a campaign to teach the public about child labor and child trafficking. The government created a hotline to report cases of restavek abuse. In December 2012, the government created a national commission to Eliminate the Worst Forms of Child Labor. This involved starting a public awareness campaign on child labor. It also highlighted a national day against restavek abuse. In early 2013, the government created a group of different ministries to work on human trafficking. This group, led by the Judicial Affairs Director of the Foreign Affairs ministry, coordinates all government efforts against trafficking.

Factors Contributing to Modern Slavery

The 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report found several reasons why human trafficking continues in Haiti. These reasons also apply to Latin America and the Caribbean.

The Haitians most at risk of becoming victims of human traffickers are the poorest people, especially children. Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Over half the population lives on less than a dollar a day. Over three-quarters live on less than two dollars a day. Extreme poverty, along with a lack of social services like education and basic healthcare, makes children more vulnerable to modern slavery. Things that increase a child's chance of becoming a restavek include illness or losing one or both parents. Also, not having access to clean water, not having educational opportunities, and having family in a city can increase the risk. Besides poverty, other individual factors that can lead to exploitation include not having a job, not being able to read or write, poor education, and homelessness. These factors "push" people toward human trafficking and modern slavery. Often, men, women, and children accept slave-like work conditions because there is little hope for a better life, and they need to survive. Some cross national borders looking for good opportunities. But instead, they find themselves part of an exploited workforce. Also, factors that make people easy targets for traffickers make enslavement more likely. One group at high risk for forced labor is internally displaced persons, especially women and children living in refugee camps. These camps offer little safety. About 10% of undocumented Haitians, whose births are not reported, are at especially high risk of enslavement.

Human trafficking along the Haitian-Dominican border continues because both countries benefit economically from the flow of undocumented migration. This directly leads to trafficking. Trafficking is a profitable business for traffickers in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. As long as there are big economic and social differences, like poverty, social exclusion, environmental problems, and political instability, between the two countries, the trade will continue.

There are also bigger reasons, beyond individual choices, that explain why modern-day slavery continues in Haiti. The U.S. State Department's Trafficking in Persons Report has identified eight such reasons in Latin America and the Caribbean:

- 1. High demand for domestic servants, farm workers, and factory labor.

- 2. Political, social, or economic problems, and natural disasters like the January 2010 earthquake.

- 3. Lingering machismo (chauvinistic attitudes) that often leads to discrimination against women and girls.

- 4. Existing trafficking networks with clever ways of finding victims.

- 5. Public corruption, especially when law enforcement and border agents work with traffickers and smugglers.

- 6. Strict immigration policies in some destination countries that limit legal ways to migrate.

- 7. Government not caring enough about human trafficking.

- 8. Limited economic opportunities for women.

The restavek tradition continues because many people in Haiti accept it. Other factors contributing to the restavek system include poverty, education, and jobs in the countryside. Poor rural families with many children have few ways to feed and educate them. This leaves them with few choices other than servitude in the city.

See also

- Human rights in Haiti

- Women's rights in Haiti

- Dominican Republic–Haiti relations

Images for kids