Alexandre Pétion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexandre Pétion

|

|

|---|---|

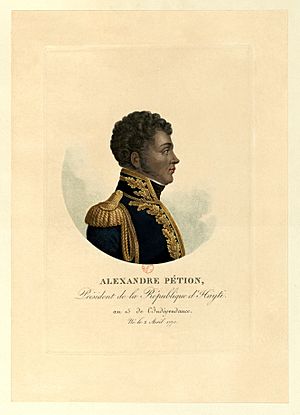

Lithograph portrait of Alexandre Pétion

|

|

| 1st President of Haiti | |

| In office March 9, 1807 – March 29, 1818 |

|

| Preceded by | Jean-Jacques Dessalines (as Emperor of Haiti) |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Pierre Boyer |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Anne Alexandre Sabès

April 2, 1770 Port-au-Prince, Saint-Domingue |

| Died | March 29, 1818 (aged 47) Port-au-Prince, Haiti |

| Nationality | Haitian |

| Spouse | Marie-Madeleine Lachenais |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

French Revolutionary Army Armée Indigène |

| Years of service | 1791–1803 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Haitian Revolution |

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (pronounced: al-ek-SAHN-druh sah-BES peh-TYOHN; born April 2, 1770 – died March 29, 1818) was a very important leader in Haiti's history. He became the first president of the Republic of Haiti in 1807 and served until his death in 1818.

Pétion was one of Haiti's founding fathers. He worked alongside other famous leaders like Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines. He was known as a skilled artilleryman and a respected military commander. He led both French and Haitian troops during the Haitian Revolution. In 1802, he joined forces with Dessalines against the French army. This alliance was a major turning point, leading to Haiti's victory at the Battle of Vertières in 1803.

Early Life and Background

Pétion was born in Port-au-Prince. His father, Pascal Sabès, was a wealthy Frenchman, and his mother, Ursula, was a free woman of mixed race. This meant Pétion was considered a quadroon, having one-quarter African ancestry.

Like many other "free people of color" (known as gens de couleur libres) whose fathers were wealthy, Pétion was sent to France in 1788. He studied at the Military Academy in Paris.

In Saint-Domingue (which is now Haiti), free people of color formed a unique group. They were not white, but they were also not enslaved. Many of them became educated and owned land. However, they had fewer political rights than white people. After the French Revolution, these free people of color fought for more rights. This happened before the major slave rebellion of 1791. At that time, most free people of color did not support freedom for enslaved people.

Role in the Haitian Revolution

Pétion returned to Saint-Domingue as a young man to join the Haitian Revolution. He fought against the British forces in northern Haiti.

There were often tensions between different groups in Saint-Domingue. The enslaved Black population was much larger than the white and mixed-race populations. Pétion often supported the mixed-race group. He joined General André Rigaud and Jean-Pierre Boyer in a conflict against Toussaint Louverture. This conflict, sometimes called the "War of Knives," started in 1799. Pétion defended the southern port of Jacmel, but the town fell in 1800. Pétion and other mixed-race leaders then went to France.

In 1802, a French general named Charles Leclerc arrived with many warships and soldiers. He wanted to bring Saint-Domingue back under French control. Pétion, Boyer, and Rigaud returned with him, hoping to gain power.

However, after the French captured Toussaint Louverture, Pétion decided to join the fight for Haiti's independence in October 1802. He supported Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who became the leader of the rebels. The rebels captured the capital, Port-au-Prince, in October 1803. Dessalines declared Haiti's independence on January 1, 1804. On October 6, 1804, Dessalines declared himself Emperor of Haiti.

After the Revolution

Some leaders, including Pétion and Henri Christophe, were unhappy with Emperor Dessalines. They planned to overthrow him. After Dessalines was killed on October 17, 1806, Pétion believed in democracy, where people have a say in their government. However, Henri Christophe wanted to rule alone. Christophe was elected president, but he felt he didn't have enough power. He went to the north of Haiti and created his own government, declaring the State of Haiti. The country became divided, with Pétion leading the south and Christophe leading the north.

Pétion was elected President of the southern Republic of Haiti in 1807. After years of fighting, a peace treaty was signed in 1810, splitting the country into two parts. In 1811, Christophe made himself king of the northern Kingdom of Haiti.

On June 2, 1816, Pétion changed the rules for the presidency, making himself president for life. Even though he first supported democracy, Pétion found the rules set by the senate difficult. He suspended the legislature in 1818.

Pétion took large farms from the rich landowners. He then gave this land to his supporters and to the farmers. This earned him the nickname Papa Bon-Cœur, which means "good-hearted father." However, these changes meant that Haiti produced fewer goods to sell to other countries. Most people became farmers who grew just enough food for themselves. This caused exports and government money to drop sharply, making it hard for the new country to survive.

Pétion believed that education was very important. He started the Lycée Pétion, a school in Port-au-Prince. He also strongly believed in freedom and democracy for everyone, especially for enslaved people around the world. He often helped those who were oppressed. In 1815, he gave a safe place to Simón Bolívar, a leader fighting for independence in South America. Pétion also gave Bolívar supplies and soldiers. This help was very important for Bolívar's success in freeing the countries that would become Gran Colombia. Pétion was said to be influenced by his partner, Marie-Madeleine Lachenais, who also advised him on political matters.

Pétion chose General Boyer to be his successor. Boyer took control in 1818 after Pétion died from yellow fever. After King Henry I of the Kingdom of Haiti and his son died in 1820, Boyer reunited the entire nation under his rule.

See Also

In Spanish: Alexandre Pétion para niños

In Spanish: Alexandre Pétion para niños