Shields Green facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Shields Green

|

|

|---|---|

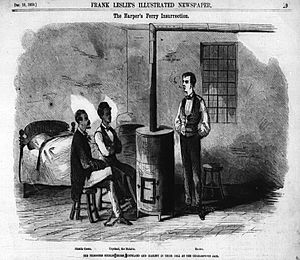

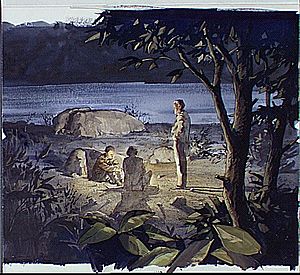

Green awaiting his trial

after the Harpers Ferry raid |

|

| Born | c. 1836 South Carolina, U.S.

|

| Died | December 16, 1859 (aged 22–23) |

| Resting place | Winchester, Virginia (grave unknown) |

| Other names | Emperor |

| Known for | Raid on Harpers Ferry |

| Criminal charge(s) | Murder and inciting a slave insurrection; charge of treason dropped |

| Criminal status | Executed |

Shields Green (born around 1836 – died December 16, 1859) was an important figure in the fight against slavery in the United States. He was an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina. Green was a key leader in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in October 1859.

He lived for about two years with Frederick Douglass, a famous abolitionist, in Rochester, New York. Douglass introduced Green to John Brown, who was planning to fight against slavery.

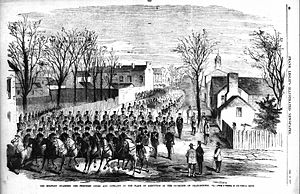

Even though Green was not hurt during the raid, he was later put on trial. He was found guilty and executed on December 16, 1859. Three other raiders were also executed with him. All the trials and executions happened in Charles Town, West Virginia. Many people watched these events.

Frederick Douglass spoke highly of Shields Green. He mentioned Green alongside other brave rebels like Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey. Shields Green was seen as a Black hero, similar to Crispus Attucks and Toussaint Louverture.

Contents

Who Was Shields Green?

Information about Shields Green is not always clear or complete. We know less about him than about other people involved in the Harpers Ferry raid.

Green was known to be a good shot with a rifle and revolver. He used his weapons "rapidly and diligently" during the raid. He was also described as "very illiterate," meaning he couldn't read or write well. He didn't write or receive letters while in jail.

Green was called "a man of few words" by Frederick Douglass. People were more interested in the white prisoners than the Black ones. There are no photographs of Green, but there are sketches by different artists.

Green's Appearance

People at the time often described Green's skin color. He was called "a negro of the blackest hue" or "a full blooded negro." During that time, people with darker skin were often treated as less important.

Because of his dark skin and his fighting skills, Green was sometimes treated harshly. He was described as "small in stature and very active." He had "a sharp, intelligent look" and a "fine, athletic figure."

His Names

The Name Emperor

Frederick Douglass said that Green called himself by different names, including "Emperor" and "Shields Green." He even had a business card that said "Shield Emperor."

Other people involved in the raid also called him "Emperor." We don't know exactly why he chose this nickname. Some people guess it might have something to do with his background or leadership among other Black people. He was described as "very officious" and "conscious of his own great importance." He was also "very insulting to Brown's prisoners," sometimes threatening them with his rifle.

Was He Esau Brown?

Some modern stories say Green's real name was Esau Brown. However, there is only one old newspaper article from 1861 that mentions this name. Most historians believe this is incorrect. Frederick Douglass and others who knew Green never used this name.

Green's Way of Speaking

Green understood speech well. He was present at long meetings and seemed to follow along without trouble.

However, Douglass noted that Green was "a man of few words, and his speech was singularly broken." This might mean he had a speech difficulty. One of John Brown's daughters, Anne Brown Adams, remembered Green giving a "farewell speech" that was a "greatest conglomeration of all the big words." She said it was hard to understand.

Despite this, some of Green's reported sentences were powerful:

- "Oh, what a poor fool I am! I had got away out of slavery, and here I have got back into the eagle’s claw again!"

- "Death from the hands of the law for no offense save for believing in liberty for myself and my race, would not be a degradation."

Green's Early Life

We don't know much about Green's life before 1857. He arrived in Rochester, New York, and stayed at Frederick Douglass's home. Douglass's home was a safe place for people who had escaped slavery.

Douglass said Green was an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina. He grew up in the city. Green claimed to be a "free negro" in court documents. However, Douglass later revealed Green's true status as an escaped slave after Green's death.

His age was reported differently, from 23 to 30 years old. Green was a widower, meaning his wife had died. He had at least one son living in Charleston, but their names are unknown. Green escaped slavery by hiding in cargo on a ship.

Meeting John Brown

A very important moment in Green's life was his meeting with John Brown and Frederick Douglass. This meeting happened in an old stone quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. It lasted for a whole day and night.

Green first met John Brown at Frederick Douglass's house in Rochester. Brown stayed there for weeks, planning his fight against slavery. Green and Douglass traveled together to Chambersburg to meet Brown. Brown had asked Douglass to bring Green because he saw Green's strong character.

The meeting was kept secret in the stone quarry. Brown wanted Douglass to join his raid, hoping Douglass's support would encourage enslaved people to join. Douglass refused because he believed the raid would fail.

Green, however, chose to stay with Brown. When Douglass suggested Green return to Rochester, Green famously said, "I b'l’eve I'll go wid de old man." He made a similar choice during the raid when it was failing.

Green and Douglass's Connection

Green was seen by some as a replacement for Douglass in Brown's plans.

In August 1859, Douglass and Green met Brown in Chambersburg. Douglass decided not to join Brown's group, as he thought it was too risky. Green, however, refused to go back with Douglass. He joined Brown's men at a rented farm in Maryland.

Some stories say Green could have escaped during the raid but chose to stay with Brown. However, another Black raider, Osborne Anderson, said Green actually got confused during the fighting and ended up staying with Brown by mistake.

Owen Brown, John Brown's son, walked with Green from Chambersburg to the Kennedy Farm. It was a dangerous 20-mile trip because of slave catchers. Owen said Green was "more mindful and alert" than he was, spotting white people first. Green was very worried about being back in a slave state. When they reached the farm, Green was "like a new man."

The Harpers Ferry Raid

During the raid, Green was supposed to help enslaved people from nearby areas join the fight. He was with Dangerfield Newby and Osborne Anderson at the Arsenal. Osborne Anderson said Green quickly got revenge for Newby's death.

Green and Edwin Coppock were the only two of Brown's raiders who were not hurt or didn't escape. Green almost shot Robert E. Lee, a famous general, but was told not to. Green was also in charge of watching the hostages in the "engine house."

Green's Trial

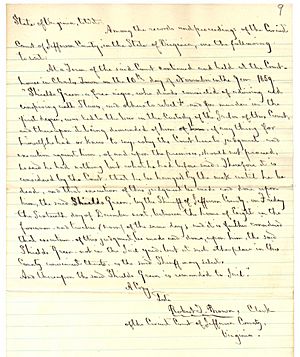

Green's trial started on November 3. The main witness against him was Lewis Washington, a relative of George Washington, who had been held hostage by Brown's men. Washington said Green was guarding the white hostages with a rifle, pistol, and knife. He also said Green fired shots at the militia.

Washington was especially upset that Green spoke to him in a "very impudent manner." Green's friends called him "Emperor" because of his confident way of acting. Frederick Douglass said Green's "courage and self-respect made him quite a dignified character."

Green's lawyer, George Sennott, argued cleverly for his defense. He used a recent court decision, the Dred Scott decision, to argue that Green could not be charged with treason. This decision said that Black people were not citizens. Because of this, the jury found Green not guilty of treason.

Green, like other defendants in Virginia at the time, could not speak in his own defense. He was found guilty of murder and trying to start a slave uprising. Green, Copeland, John Edwin Cook, and Edwin Coppock were all sentenced to death on November 10.

On the morning of John Brown's execution, Green sent a message saying he was glad he had fought with Brown and was ready for his own death.

Green's Execution

Shields Green and John Copeland were executed on Friday, December 16, two weeks after John Brown.

Legacy and Honors

- On December 25, 1859, a special service was held in Oberlin, Ohio, for Copeland, Green, and Lewis Sheridan Leary, who died during the raid.

- A monument was built in 1865 in Oberlin to honor these three "citizens of Oberlin." It was moved in 1971 to Martin Luther King Jr. Park. The monument says:

These colored citizens of Oberlin, the heroic associates of the immortal John Brown, gave their lives for the slave.

Et nunc servitudo etiam mortua est, laus deo [And now slavery is finally dead, thanks be to God].

S. Green died at Charleston, Va., Dec. 16, 1859, age 23 years.

J. A. Copeland died at Charleston, Va., Dec. 16, 1859, age 25 years.

L. S. Leary died at Harper's Ferry, Va., Oct. 20, 1859, age 24 years.

- The Green–Copeland American Legion Post 63 was started in Charles Town, West Virginia, in 1929.

- Shields Green has been featured in books, plays, and movies.

- A 1983 play, When My Bees Swarm, tells the story of the meeting between Brown, Douglass, and Green.

- He was called "Rochester's first black martyr" in a 1986 book.

- The meeting of Brown, Douglass, and Green is also shown in the 2013 PBS miniseries, The Abolitionists.

- The 2020 film Emperor is based on Green's life.

- Green also appears in The Good Lord Bird (miniseries) from 2020.

Images for kids

See also

- John Brown's raiders

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |