History of the Southern United States facts for kids

The history of the Southern United States goes back thousands of years. The first people to live there were the Paleo-Indians. They were the very first Native Americans in the Americas. By the 15th century, when Europeans arrived, the region was home to the Mississippian people. These people were famous for building large mounds of earth.

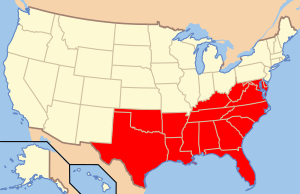

European history in the South began with early exploration and colonization of North America. Countries like Spain, France, and England explored and claimed parts of what is now the Southern United States. Their cultures still influence the region today. Over the centuries, many important events happened in the South. These include the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the American Civil War. Slavery expanded and then ended in the U.S. There were also big movements of African Americans, like the First Great Migration and the Second Great Migration. The Jim Crow era and the American Civil Rights Movement were also key times. Later, the 1996 Summer Olympics were held in Atlanta. The South also saw big changes in its economy and population in the late 20th century. After World War II, industries grew quickly. Since the late 20th century, many people from other U.S. regions and other countries have moved to the South.

Contents

- Ancient Native American Cultures

- European Explorers Arrive

- British Colonies (1607–1775)

- American Revolution (1775–1783)

- Before the Civil War (1783–1861)

- The Civil War (1861–1865)

- Rebuilding the South (1865–1877)

- The Rural South in the Early Years

- The New South Emerges

- Changes in the Black Belt Farming System

- The South and U.S. Foreign Policy

- The South from Mid-20th Century to Today

- U.S. Presidents from the South

Ancient Native American Cultures

Before Europeans arrived, only Native Americans lived in the Southern United States. When Europeans first made contact, much of the area was home to the Mississippian culture. This was a farming culture that thrived in the Midwest, East, and Southeast of the U.S. The Mississippian way of life started around the 10th century. It began in the Mississippi River Valley, which is where it gets its name.

Some famous Native American groups developed in the South after the Mississippians. These are known as "the Five Civilized Tribes". They include the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations.

European Explorers Arrive

Spanish Explorers Seek New Lands

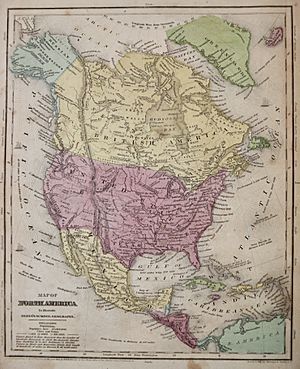

Spain sent many explorers to the New World after it was discovered in 1492. Stories of gold and a Fountain of Youth kept many Spanish explorers interested. Soon, they began to set up colonies. Juan Ponce de León was the first European to reach the South. He landed in Florida in 1513.

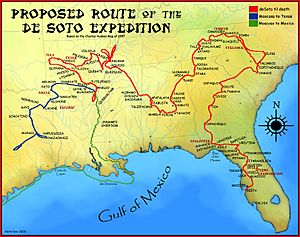

Hernando de Soto, a Spanish explorer and conquistador, led the first big European trip deep into the modern-day Southern U.S. He was looking for gold and a way to China. De Soto's group was the first documented European group to cross the Mississippi River. De Soto himself died on its banks in 1542. (Alonso Álvarez de Pineda was the first European to see the river in 1519. He sailed twenty miles up from the Gulf of Mexico).

De Soto's journey was huge. It covered parts of modern Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas.

Some of the first European settlements in North America were Spanish. They were in what later became Florida. The earliest was Tristán de Luna y Arellano's failed colony in Pensacola in 1559. More successful was Pedro Menéndez de Avilés's St. Augustine, founded in 1565. St. Augustine is still the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the U.S. Spain also colonized parts of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Spain gave out land grants in the South from Kentucky to Florida. There was even a Spanish colony near King Powhatan's town in the Chesapeake Bay area. This was in what is now Virginia and Maryland. It was there about 100 years before the English colony of Jamestown.

French Settlers Come to the South

The first French settlement in the Southern U.S. was Fort Caroline. It was located in what is now Jacksonville, Florida, in 1562. It was meant to be a safe place for Huguenots (French Protestants). It was founded by René Goulaine de Laudonnière and Jean Ribault. The Spanish from St. Augustine destroyed it in 1565.

Later, French explorers came from the north. They had set up farms in Canada. They also built a fur trading network with Native Americans near the Great Lakes. Then, they began to explore the Mississippi River. The French named their territory Louisiana, after their King Louis. France also claimed Texas. They built several short-lived forts there, like one in Red River County in 1718. In 1817, the French pirate Jean Lafitte settled on Galveston Island. His colony grew to over 1,000 people by 1818 but was abandoned in 1820. The most important French settlements were in New Orleans and Mobile (originally called Bienville). Only a few settlers came directly from France. Others arrived from Haiti and Acadia.

British Colonies (1607–1775)

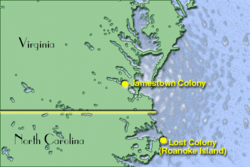

The English started exploring the New World just before they defeated the Spanish Armada. In 1585, Walter Raleigh organized an expedition. It set up the first English settlement in the New World on Roanoke Island, North Carolina. But the colony struggled. The colonists were taken back to England the next year. In 1587, Raleigh sent another group to Roanoke. The first recorded European baby born in North America, Virginia Dare, was from this colony. This group of colonists disappeared and is known as the "Lost Colony." Many people think they were either killed or joined local tribes.

Like New England, the South was first settled by English Protestants. The English set up their first lasting colony in America in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. It was at the mouth of the James River, which flows into Chesapeake Bay.

People settled in Chesapeake Bay hoping to find gold. The colony was technically in Spanish territory. But it was far enough from most Spanish settlements to avoid fights. This region, called the "Anchor of the South," includes the Delmarva Peninsula and much of coastal Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

Early on, it became clear that there was not much gold. The years from 1607 to 1609 were called the "Starving Time" for the Jamestown colony. There was famine and instability. However, Native American help and new supplies from Britain kept the small colony going. But because of ongoing political and economic problems, the Colony of Virginia's charter was canceled in 1624. This happened mainly because hundreds of settlers died or went missing after a 1622 attack by Native American tribes led by Opechancanough. Virginia then became a royal colony. But the House of Burgesses, formed in 1619, was allowed to continue leading the colony with a royal governor.

William Berkeley was a very important person in the Virginia Colony. He was governor of Virginia from 1645 to 1675, with some breaks. He wanted wealthy English people to move to Virginia. He started a "Second Sons" policy, inviting younger sons of English nobles to move there. Berkeley also pushed the headright system. This gave large areas of land to people who came to the colony. This early arrival of wealthy people helped create an aristocratic (upper-class) political and social system in the South.

English colonists, especially young indentured servants, kept arriving along the southern Atlantic coast. Virginia became a rich English colony. The area now called Georgia was also settled. It started as a place for imprisoned debtors to restart their lives, led by James Oglethorpe.

Tobacco, Cotton, and the Rise of Slavery

When tobacco was introduced in 1613, growing it became the main part of the early Southern economy. Cotton did not become a major crop until much later. This was after new inventions, especially Whitney's cotton gin in 1794, made cotton farming much more profitable. Before that, most cotton was grown on large farms in the Province of Carolina. Tobacco, which could be grown on smaller farms, was the main cash crop exported from the South and the Middle Colonies.

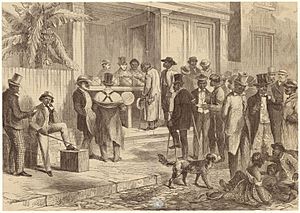

In 1640, the Virginia General Court recorded the first time someone was sentenced to lifelong slavery. This was John Punch, who ran away from his master.

During this time, people often did not live very long. Indentured servants came from crowded parts of Europe. Servants were cheaper than slaves. Also, many servants died young. So, farmers often found it cheaper to use servants.

Because of this, slavery in the early colonies was different from slavery in the Caribbean. In the Caribbean, slaves were often worked to death on big sugar and rice plantations. But in the American colonies, the slave population lived longer. It grew through natural reproduction. This natural growth was important for slavery to continue after importing slaves became illegal around 1780.

Much of the slave trade was part of the "triangular trade". This was a three-way exchange of slaves, rum, and sugar. Northern shippers bought slaves using rum, which was made in New England from cane sugar grown in the Caribbean. This slave trade generally met the South's need for workers to grow tobacco after fewer indentured servants arrived. Around the time tobacco farming needed more workers, the death rate fell, and all groups lived longer. By the late 1600s and early 1700s, slaves became a good source of labor for the growing tobacco farms. Further south than the Mid-Atlantic, Southern settlers also became rich by growing and selling rice, indigo, and cotton. The plantations in South Carolina were often like Caribbean plantations, but smaller.

Southern Colonies Grow and Change

By the end of the 17th century, the number of colonists was increasing. The economies of the Southern colonies depended on farming. During this time, large plantations were formed by wealthy colonists. They saw great opportunities in the new country. Tobacco and cotton were the main cash crops. English buyers eagerly bought them. Rice and indigo were also grown and sent to Europe. Plantation owners built a rich, aristocratic life. They gained a lot of wealth from their land. They used slavery to work their land. On the other side were the small yeoman farmers. They did not have the money or ability to run large plantations. Instead, they worked small pieces of land. They became politically active against the growing power of the plantation owners. Many politicians from this time were yeoman farmers. They spoke out to protect their rights as free men.

Charleston became a busy trade town for the southern colonies. Many pine trees in the area provided wood for shipyards. The harbor was a safe port for English ships bringing in goods. The colonists exported tobacco, indigo, and rice. They imported tea, sugar, and slaves.

After the late 17th century, the economies of the North and South began to become different. This was especially true in coastal areas. The South focused on producing goods for export. The North focused on producing food.

By the mid-18th century, the colonies of Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia were established. In the upper colonies (Maryland, Virginia, and parts of North Carolina), tobacco farming was most common. But in the lower colonies of South Carolina and Georgia, farming focused more on cotton and rice.

American Revolution (1775–1783)

The southern colonies, led by Virginia, strongly supported the Patriot cause. They stood with Massachusetts. Georgia, the newest and smallest colony, hesitated. It was very exposed and weak militarily. But it soon joined the other 12 colonies in Congress. As soon as news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord arrived in April 1775, Patriot forces took control of every colony. They used secret committees that had been set up in the previous two years. After fighting began, Governor Dunmore of Virginia had to flee to a British warship. In late 1775, he offered freedom to slaves who escaped from Patriot owners and joined the British Army. Over 1,000 volunteered and served in British uniforms. Most were in the Ethiopian Regiment. However, they were defeated in the Battle of Great Bridge. Most of them died of disease. The Royal Navy took Dunmore and other officials home in August 1776. They also carried 300 surviving former slaves to freedom.

After their defeat at Saratoga in 1777, and with France joining the American Revolutionary War, the British focused on the South. They had fewer regular troops. So, British commanders planned a "southern strategy." This plan relied heavily on volunteer soldiers and militia from the Loyalist (pro-British) side.

Starting in late December 1778, the British captured Savannah. They controlled the Georgia coastline. In 1780, they seized Charleston, capturing a large American army. A big victory at the Battle of Camden meant royal forces soon controlled most of Georgia and South Carolina. The British set up forts inland. They expected Loyalists to join them. But too few Loyalists showed up. The British had to fight their way north into North Carolina and Virginia with a very weak army. Behind them, most of the territory they had captured fell into a chaotic guerrilla war. This was mostly fought between Loyalist and Patriot militias. The Patriots retook the areas the British had gained.

The British army marched to Yorktown, Virginia. They expected a British fleet to rescue them. The fleet arrived, but so did a larger French fleet. So, the British fleet returned to New York for help. This left General Cornwallis trapped by much larger American and French armies under Washington. He surrendered. The most important Loyalists, especially those who joined Loyalist regiments, were taken by the Royal Navy back to England, Canada, or other British colonies. They brought their slaves, but lost their land. Other Loyalists who stayed in the southern states became American citizens when the United States was formed.

Before the Civil War (1783–1861)

After the American Revolution ended around the Siege of Yorktown (1781), the South became a major political power in the United States. With the Articles of Confederation, the South found political stability. There was little federal interference in state matters. However, this system was weak. The Confederation could not keep the economy strong. This led to the creation of the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787. It is important to note that Southerners in 1861 often felt their efforts to secede and the Civil War were like a "replay" of the American Revolution.

Southern leaders protected their regional interests during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. They stopped any clear anti-slavery statements from being put in the Constitution. They also made sure the "fugitive slave clause" and the "Three-Fifths Compromise" were included. Still, Congress kept the power to control the slave trade. Twenty years after the Constitution was approved, Congress banned the import of slaves, starting January 1, 1808. While North and South found common ground for a strong Union, the Constitution hid deep differences in economic and political interests. After the 1787 convention, two different ideas of American government emerged.

In the South, a farming-based, hands-off approach to government shaped political culture. Led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, this farming view is seen in Jefferson's grave marker. It mentions his role in founding the University of Virginia and writing the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. But it does not mention his role as President of the United States. Southern political thought focused on the idea of the yeoman farmer. This meant that those tied to the land also had a strong interest in the government's stability and survival.

Slavery Before the War

In the North, slaves were mostly house servants or farm workers. Every Northern state ended slavery by 1804. The Continental Congress also banned slavery in the Northwest Territory and its future states. So, by 1804, the Mason–Dixon line (the border between free Pennsylvania and slave Maryland) became the dividing line between "free" and "slave" states.

About one-third of white Southern families owned slaves. Most of these were independent yeoman farmers. However, the slave system was the base of the Southern social and economic system. So, even non-slaveowners were against any ideas of ending slavery, whether completely or one by one.

The Southern plantation economy relied on foreign trade. The success of this trade helps explain why Southern elites and some white yeomen were so strongly against ending slavery. There is much debate among experts about whether the slaveholding South was a capitalist society and economy.

States' Rights and Growing Differences

Although slavery was not yet the main issue, states' rights came up often in the early period before the Civil War. This was especially true in the South. The election of Federalist John Adams in the 1796 presidential election happened as tensions with France grew. In 1798, the XYZ Affair brought these tensions to a head. Adams worried about French power in America. He feared internal sabotage and unrest caused by French agents. To respond to this and to attacks on Adams and the Federalists by Democratic-Republican publishers, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws led to the jailing of "seditious" Democratic-Republican editors in the North and South. This caused the legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia to adopt the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 (written by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison).

Thirty years later, during the Nullification Crisis, leaders in South Carolina used these "Principles of '98" to justify states' power. They claimed states could nullify, or stop the local use of, federal laws they thought were unconstitutional. The Nullification Crisis started because of the Tariff of 1828. This was a set of high taxes on imported manufactured goods. Congress passed it to protect American industries, mainly in the North. In 1832, South Carolina's legislature nullified the entire "Tariff of Abominations," as the Tariff of 1828 was called in the South. This led to a standoff between the state and the federal government. On May 1, 1833, President Andrew Jackson wrote, "the tariff was only a pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question." The crisis was solved by the president's actions, Congress lowering the tariff, and the Force Bill. But it was important for later ideas about secession. Another factor that led to Southern differences was the growth of cultural and literary magazines like the Southern Literary Messenger and DeBow's Review.

Slavery and New Territories

Another issue causing differences was slavery. Especially, whether to allow slavery in western territories that wanted to become states. In the early 1800s, as cotton farming grew, slavery became more profitable on a large scale. More Northerners began to see it as an economic threat, even if they didn't care about its moral side. While few Northerners wanted to abolish slavery completely, many more opposed its spread to new territories. They believed that having slaves lowered wages for free workers.

At the same time, Southerners increasingly felt threatened by the North's economic and population growth. For decades after the Union was formed, as new states joined, North and South managed their differences. They kept political balance by admitting "slave" and "free" states in equal numbers. This compromise kept the balance of power in the Senate. However, the House of Representatives was different. As the North industrialized and its population grew (helped by many European immigrants), the Northern majority in the House also grew. This made Southern political leaders very uncomfortable. Southerners worried they would soon be at the mercy of a federal government where they no longer had enough power to protect their interests. By the late 1840s, Senator Jefferson Davis from Mississippi said the new Northern majority in Congress would make the U.S. government "an engine of Northern aggrandizement." He believed Northern leaders wanted to "promote the industry of the United States at the expense of the people of the South."

After the Mexican–American War, many Northerners worried about new land added on the Southern side of the free-slave line. The issue of slavery in the territories became very heated. After four years of conflict, the Compromise of 1850 barely avoided civil war. It was a complex deal. California was admitted as a free state, including Southern California, preventing a separate slave territory there. Slavery was allowed in the New Mexico and Utah territories. A stronger Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed. It required all citizens to help capture runaway slaves wherever they were found. Four years later, the peace bought by these compromises finally ended. In the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Congress let each territory vote on slavery. This caused chaos as pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers competed to populate the new region.

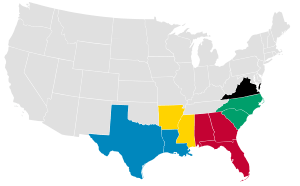

The Civil War (1861–1865)

The states that left the Union formed the Confederate States of America. They only wanted to be independent. They did not want to conquer any state north of their border. After they seceded, no compromise was possible. The Confederacy insisted on its independence. The Lincoln Administration refused to meet with President Davis's representatives. Instead of talking, Lincoln ordered a Navy fleet to Charleston Harbor. Its mission was to reinforce and resupply Fort Sumter. Just before the fleet entered the harbor, Confederates forced the Federal soldiers in the fort to surrender. This event, though only a cannon fight with no deaths, allowed President Lincoln to say that U.S. forces had been attacked. This justified his call for troops to invade the seceded states. In response, the Confederate military wanted to hold its territory. It also wanted to gain worldwide recognition. They hoped to inflict so much damage on invaders that Northerners would get tired of the expensive war. They wanted a peace treaty that would recognize the Confederacy's independence. Two Confederate attacks into Maryland and southern Pennsylvania failed to influence federal elections as hoped. Lincoln and his party winning the 1864 elections meant the Union's military victory was only a matter of time.

Both sides wanted the border states. But the Union military took control of all of them in 1861–1862. Union victories in western Virginia allowed a Unionist government in Wheeling to take control of western Virginia. With Washington's approval, they created the new state of West Virginia. The Confederacy did recruit troops in the border states. But the Union gained a huge advantage by controlling them.

| Union | CSA | |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 22,000,000 (71%) | 9,000,000 (29%) |

| Free population | 22,000,000 | 5,500,000 |

| 1860 Border state slaves | 432,586 | NA |

| 1860 Southern slaves | NA | 3,500,000 |

| Soldiers | 2,200,000 (67%) | 1,064,000 (33%) |

| Railroad miles | 21,788 (71%) | 8,838 (29%) |

| Manufactured items | 90% | 10% |

| Firearm production | 97% | 3% |

| Bales of cotton in 1860 | Very little | 4,500,000 |

| Bales of cotton in 1864 | Very little | 300,000 |

| Pre-war U.S. exports | 30% | 70% |

The Union naval blockade, starting in May 1861, cut exports by 95%. Only small, fast blockade runners, mostly owned by British companies, could get through. The South's huge cotton crops became almost worthless.

In 1861, the rebels thought that "King Cotton" was so powerful. They believed that if Europe lost its cotton supply, Britain and France would join the war to help the South. Confederate leaders did not know much about Europe. Britain depended on the Union for its food supply. It would not benefit from a very expensive major war with the U.S. The Confederacy moved its capital from a safe place in Montgomery, Alabama, to the bigger city of Richmond, Virginia. Richmond was only 100 miles (160 km) from Washington. Richmond had the history and facilities to match Washington. But its closeness to the Union forced the Confederacy to use most of its war efforts to defend Richmond.

War Leadership

The Confederacy had a very strong group of officers. About one-third of the U.S. Army officers had resigned and joined them. But the political leaders were not very effective. Many historians say the Confederacy "died of states' rights". This means that governors of Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina refused Richmond's requests for troops.

The Confederacy decided not to have political parties. They strongly felt that parties caused division and would weaken the war effort. However, historians agree that not having parties weakened their political system. Without a different option, people could only complain and lose faith.

Historians generally think President Jefferson Davis was much less effective than Abraham Lincoln. As a former Army officer, senator, and Secretary of War, he had the experience to be president. But some character flaws hurt his performance. He played favorites and was bossy, cold, and argumentative. By not having parties, he missed the chance to build a network of support from ordinary people. This support was badly needed in tough times. Instead, he took all the blame for difficulties and disasters. Davis had a strong vision of a powerful, rich new nation, the Confederate States of America. It was based on the right of its white citizens to govern themselves. However, unlike Lincoln, he could never clearly explain that vision or create a clear plan to fight the war. He ignored the Confederacy's civilian needs. He spent too much time getting involved in military details. Davis's interference in military strategy was counterproductive. His clear orders that Vicksburg must be held at all costs ruined the only possible defense. This led directly to the fall of the city in 1863.

Ending Slavery

By 1862, most Northern leaders realized they had to directly attack slavery. Slavery was the main reason for Southern secession. All the border states rejected President Lincoln's idea for compensated emancipation (paying slave owners to free slaves). However, by 1865, all had started to abolish slavery, except Kentucky and Delaware. The Emancipation Proclamation was an order given by Lincoln on January 1, 1863. It instantly changed the legal status of 3 million slaves in specific Confederate areas from "slave" to "free." This meant that as soon as a slave escaped Confederate control, by running away or through federal troops advancing, the slave became legally and actually free. Plantation owners knew that emancipation would destroy their economic system. So, they sometimes moved their slaves as far as possible from the Union Army. By June 1865, the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy. It freed all the designated slaves. The owners were never paid. Neither were the slaves themselves. Many freed people stayed on the same plantation. Others went to refugee camps run by the Freedmen's Bureau. The Bureau provided food, housing, clothing, medical care, church services, some schooling, legal help, and arranged work contracts.

Historian Leon Litwack noted, "Neither white nor black Southerners were unaffected by the physical and emotional demands of the war. Shortages of food and clothing, for example, caused hardships for both races." Conditions were worse for black people. Late in the war and soon after, many black people moved away from plantations. The Freedmen's Bureau refugee camps saw infectious diseases like smallpox become epidemics. Jim Downs states:

- Disease and sickness had more devastating and fatal effects on emancipated slaves than on soldiers, since ex-slaves often lacked the basic necessities to survive. Emancipation liberated bondspeople from slavery, but they often lacked clean clothing, adequate shelter, proper food, and access to medicine in their escape toward Union lines. Many free slaves died once they secured refuge behind union camps.

Railroads During the War

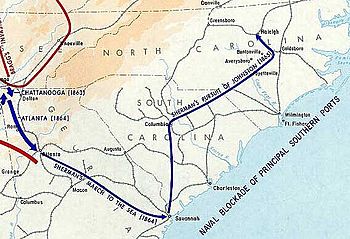

The Union had three times more railroad mileage. More importantly, they had a huge advantage in engineers and mechanics. These workers were in the mills, machine shops, factories, and repair yards that made and maintained rails, bridges, trains, and telegraph equipment. In peacetime, the South imported all its railroad equipment from the North. The Union blockade completely stopped these imports. Southern lines were mostly for short trips, like from cotton fields to rivers or ocean ports. They were not built for trips over 100 miles. Such trips involved many train changes and long stops. The South's 8,500 miles (13,700 km) of track was enough for essential military traffic along some internal lines, if it could be defended and maintained. As the system broke down due to worn-out equipment, accidents, and sabotage, the South could not build or even repair new trains, cars, or tracks. Little new equipment arrived. Rails in distant areas like Florida were removed and used more efficiently in war zones. Union cavalry raids often destroyed trains, cars, rails, and bridges. By the end of the war, the Southern railroad system was completely ruined. Meanwhile, the Union army rebuilt rail lines to supply its forces. A Union railroad through enemy territory, like from Nashville to Atlanta in 1864, was a vital but fragile lifeline. It took a whole army to guard it, because every foot of track had to be secure. Many Union soldiers were on guard duty throughout the war. They were always ready for action, but rarely saw fighting.

Southern Unionists

Southerners who were against the Confederate cause during the Civil War were called Southern Unionists. They were also known as Union Loyalists or Lincoln's Loyalists. In the eleven Confederate states, states like Tennessee (especially East Tennessee), Virginia (which included West Virginia at the time), and North Carolina had the most Unionists. Many areas of Southern Appalachia also had pro-Union feelings. As many as 100,000 men living in Confederate-controlled states served in the Union Army or pro-Union guerrilla groups. Southern Unionists came from all social classes. But most were different socially, culturally, and economically from the region's main pre-war plantation owners.

Sherman's March

By 1864, top Union generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman realized the Confederate armies' weakest point was the South's crumbling infrastructure. So, they increased efforts to wear it down. Cavalry raids were a favorite tactic. Their goal was to ruin railroads and bridges. Sherman's idea was deeper. He focused on the rebels' trust in their Confederacy as a living nation. He aimed to destroy that trust. He predicted his raid would "show the South's weakness, and make its people feel that war and individual ruin are the same thing." Sherman's March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah in late 1864 burned and ruined every part of the industrial, commercial, transportation, and farming infrastructure it touched. But the actual damage was limited to about 15% of Georgia. Sherman attacked Georgia in October, right after the harvest. This was when food supplies for the next year had been gathered and were easy to destroy. In early 1865, Sherman's army moved north through the Carolinas. This campaign was even more destructive than the march through Georgia. More impactful than the twisted rails, smoking main streets, dead cattle, burning barns, and ransacked houses was the bitter realization among civilians and soldiers throughout the remaining Confederacy. They knew that if they kept fighting, sooner or later their homes and communities would suffer the same fate.

The war effectively ended with the surrender at Appomattox Court House in April 1865. There were no trials for rebellion or treason. Only one war crimes trial took place.

Rebuilding the South (1865–1877)

The Reconstruction era began after the Civil War ended in 1865. It lasted until 1877. During this time, the Union Army took control of former Confederate states, except for Tennessee. The start and end times of Union Army occupation varied by state. Slavery ended. The large slave-based plantations were mostly divided into smaller farms of 20–40 acres (8.1–16.2 ha). These were worked by tenants or sharecroppers. Many white farmers (and some black farmers) owned their land. However, sharecropping, along with tenant farming, became very common in the cotton South from the 1870s to the 1950s, for both black and white people. By the 1960s, both systems had mostly disappeared. Sharecropping was a way for very poor farmers to make a living from land owned by someone else. The landowner provided land, housing, tools, and seeds, and maybe a mule. A local merchant provided food and supplies on credit. At harvest time, the sharecropper received a share of the crop (from one-third to one-half, with the landowner taking the rest). The farmer used his share to pay his debt to the merchant. The system started with black people when large plantations were divided. By the 1880s, white farmers also became sharecroppers. This system was different from tenant farming. A tenant farmer rented the land, provided his own tools and mule, and received half the crop. Landowners watched sharecroppers more closely than tenant farmers.

Damage and Losses from the War

Reconstruction happened while a once-rich economy was in ruins. According to Hesseltine (1936):

Throughout the South, fences were down, weeds had overrun the fields, windows were broken, live stock had disappeared. The assessed valuation of property declined from 30 to 60 percent in the decade after 1860. In Mobile, business was stagnant; Chattanooga and Nashville were ruined; and Atlanta's industrial sections were in ashes.

Estimates for Confederate losses were 94,000 killed in battle, 164,000 who died of disease, and 26,000 who died in Union prisons. Estimates for Union losses were 110,000 killed in battle, 225,000 who died of disease, and 30,000 who died in Confederate prisons. More Northern soldiers died than Southern soldiers in total numbers. But the proportion of the population affected was two-thirds smaller in the North.

The number of civilian deaths during the war is unknown. But it was highest among refugees and former slaves. Most of the war was fought in Virginia and Tennessee. But every Confederate state was affected. Also affected were the border states of Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Indian Territory. Pennsylvania was the only Northern state to see major fighting, during the Gettysburg Campaign. In the Confederacy, there was little military action in Texas and Florida. Out of 645 counties in 9 Confederate states (not including Texas and Florida), Union military action occurred in 56% of them. These counties held 63% of the white people and 64% of the slaves in 1860. However, by the time the fighting happened, some people had fled to safer areas. So, the exact population exposed to war is unknown.

In 1861, the Confederacy had 297 towns and cities with 835,000 people. Of these, 162 towns with 681,000 people were occupied by Union forces at some point. Ten were destroyed or badly damaged by war. These included Atlanta (with 9,600 people in 1860), Columbia, and Richmond (with 8,100 and 37,900 people before the war, respectively). Also, much of Charleston was destroyed in an accidental fire in 1861. These eleven towns had 115,900 people in the 1860 census, which was 14% of the urban South. Historians have not estimated their population when they were invaded. The number of people who lived in the destroyed towns was just over 1% of the Confederacy's population. Also, 45 courthouses were burned (out of 830). The South's agriculture was not very mechanized. The value of farm tools and machinery in the 1860 Census was $81 million. By 1870, it was 40% less, or $48 million. Many old tools broke from heavy use and could not be replaced. Even repairs were hard.

The economic disaster in the South during the war affected every family. Except for land, most assets and investments disappeared with slavery. But debts remained. Worst of all were the deaths and injuries. Most farms were still there. But most had lost their horses, mules, and cattle. Fences and barns were in bad shape. Cotton prices had dropped. Rebuilding would take years and need outside money because the destruction was so complete. One historian summarized the collapse of the transportation system needed for economic recovery:

One of the greatest calamities which confronted Southerners was the havoc wrought on the transportation system. Roads were impassable or nonexistent, and bridges were destroyed or washed away. The important river traffic was at a standstill: levees were broken, channels were blocked, the few steamboats which had not been captured or destroyed were in a state of disrepair, wharves had decayed or were missing, and trained personnel were dead or dispersed. Horses, mules, oxen, carriages, wagons, and carts had nearly all fallen prey at one time or another to the contending armies. The railroads were paralyzed, with most of the companies bankrupt. These lines had been the special target of the enemy. On one stretch of 114 miles in Alabama, every bridge and trestle was destroyed, cross-ties rotten, buildings burned, water-tanks gone, ditches filled up, and tracks grown up in weeds and bushes. ... Communication centers like Columbia and Atlanta were in ruins; shops and foundries were wrecked or in disrepair. Even those areas bypassed by battle had been pirated for equipment needed on the battlefront, and the wear and tear of wartime usage without adequate repairs or replacements reduced all to a state of disintegration.

Railroad mileage was mostly in rural areas. The war followed the rails. Over two-thirds of the South's rails, bridges, rail yards, repair shops, and trains were in areas reached by Union armies. These armies systematically destroyed what they could. The South had 9,400 miles (15,100 km) of track, and 6,500 miles (10,500 km) were in areas reached by Union armies. About 4,400 miles (7,100 km) were in areas where Sherman and other Union generals had a policy of destroying the rail system. Even in untouched areas, lack of maintenance and repair, no new equipment, heavy overuse, and the Confederates moving equipment from distant areas to the war zone meant the system would be almost ruined by the war's end.

Political Reconstruction

Reconstruction was the process of states returning to full status in the Union. It happened in four stages, which varied by state. Tennessee and the border states were not affected. First came the governments appointed by President Andrew Johnson from 1865–66. The Freedmen's Bureau was active. It helped refugees, set up work contracts for freedmen, and created courts and schools for them. Second came rule by the U.S. Army. They held elections that included all freedmen. They excluded over 10,000 former Confederate leaders. Third was "Radical Reconstruction" or "Black Reconstruction." A Republican group governed the state. This group included freedmen, scalawags (Southern white people who supported Reconstruction), and carpetbaggers (people who moved from the North). Violent resistance by the Ku Klux Klan and similar groups was stopped by President Ulysses S. Grant. He used federal courts and soldiers strongly. The Reconstruction governments spent a lot of money on railroad support and schools. But they quadrupled taxes. This caused a tax revolt among conservatives. Stage four was reached by 1876. The white conservative group, called "Redeemers," had won political control of all states except South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. The disputed presidential election of 1876 depended on these three states, where there was much violence. The result was the Compromise of 1877. Republican Rutherford Hayes became president. All federal troops were removed from the South. This led to the quick collapse of the last Republican state governments in the 19th century.

Railroad Rebuilding

Building a new, modern rail system was seen as key to the South's economic recovery. Modernizers invested in a "Gospel of Prosperity." Money from the North helped rebuild and greatly expand railroads across the South. They were updated in terms of rail gauge, equipment, and service standards. The Southern network grew from 11,000 miles (18,000 km) in 1870 to 29,000 miles (47,000 km) in 1890. Railroads helped create a group of skilled mechanics. They also ended the isolation of much of the region. However, there were few passengers. And besides hauling cotton during harvest, there was little freight traffic. Northerners mostly owned and directed the lines. They often had to pay large bribes to corrupt politicians for needed laws.

The Panic of 1873 stopped expansion everywhere in the United States. Many Southern lines went bankrupt or could barely pay the interest on their loans.

Reaction to Reconstruction

Reconstruction was a hard time for many white Southerners. They found themselves without many basic rights of citizenship, like the right to vote. Reconstruction was also a time when many African Americans began to gain these same rights for the first time. The 13th Amendment outlawed slavery. The 14th Amendment granted full U.S. citizenship to African Americans. The 15th Amendment gave black males the right to vote. Because of these, African Americans in the South began to have more rights than ever before.

A strong reaction to the defeat and changes in society began immediately. Vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan appeared in 1866. They were the first line of rebels. They attacked and killed both freedmen and their white supporters. By the 1870s, more organized groups, like the White League and Red Shirts, worked to remove Republicans from office. They also stopped or scared black people from voting.

The Rural South in the Early Years

The South remained mostly rural until World War II. In the decades before the 1940s, there were only a few large cities scattered around. Small courthouse towns served the mostly rural population. Local politics centered around the politicians and lawyers at the courthouse. Mill towns, mainly for making textiles or tobacco products, began opening in the Piedmont region, especially in the Carolinas. Racial segregation and clear signs of inequality were common in many rural areas and rarely challenged. Black people who crossed the color line could be expelled or lynched. Cotton became even more important than before, even though prices were much lower. The number of small farms in rural areas grew over time. They became smaller and smaller as the population increased.

Many white farmers, and some black farmers, were tenant farmers. They owned their work animals and tools, and rented their land. Others were day laborers or poor sharecroppers. They worked under the landowner's supervision. Sharecropping was a way for farmers without land (both black and white) to make a living. The landowner provided land, housing, tools, and seeds, and maybe a mule. A local merchant loaned money for food and supplies. At harvest time, the sharecropper received a share of the crop (from one-third to one-half). This paid off his debt to the merchant. By the late 1860s, white farmers also became sharecroppers. The sharecropper system was a step below that of the tenant farmer. A tenant farmer rented the land, provided his own tools and mule, and received half the crop. Landowners supervised sharecroppers more closely than tenant farmers.

There was little cash circulating. Most farmers operated on credit accounts from local merchants. They paid off their debts at cotton harvest time in the fall. Although there were small country churches everywhere, there were only a few run-down schools in rural areas. High schools were available in cities, but hard to find in most rural areas. All Southern high schools combined graduated 66,000 students in 1928. School terms were shorter in the South. Total spending per student was much lower. Nationwide, elementary and secondary students attended 140 days of school in 1928. White children in the South attended 123 days, and black children 95 days. The national average in 1928 for school spending was $70,700 for every 1,000 children aged 5–17. Only Florida reached that level. Seven of the eleven Southern states spent under $31,000 per 1,000 children. Conditions were slightly better in newer growing areas, like Texas and central Florida. The deepest poverty was in South Carolina, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Hookworm and other diseases weakened many Southerners in rural areas.

The New South Emerges

The classic history of this period was written by C. Vann Woodward. It's called The Origins of the New South: 1877–1913. It was published in 1951. Sheldon Hackney explains:

Of one thing we may be certain at the outset. The durability of Origins of the New South is not a result of its ennobling and uplifting message. It is the story of the decay and decline of the aristocracy, the suffering and betrayal of the poor whites, and the rise and transformation of a middle class. It is not a happy story. The Redeemers are revealed to be as venal as the carpetbaggers. The declining aristocracy are ineffectual and money hungry, and in the last analysis they subordinated the values of their political and social heritage in order to maintain control over the black population. The poor whites suffered from strange malignancies of racism and conspiracy-mindedness, and the rising middle class was timid and self-interested even in its reform movement. The most sympathetic characters in the whole sordid affair are simply those who are too powerless to be blamed for their actions.

Race: From Jim Crow to Civil Rights

After the Redeemers took control in the mid-1870s, Jim Crow laws were created. These laws legally enforced racial segregation in public places and services. The phrase "separate but equal" was supported by the Supreme Court in the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson. This meant that white and black people should have separate but supposedly equal facilities. It wasn't until 1954 that Plessy was overturned in Brown v. Board of Education. And only in the late 1960s was segregation fully ended by laws passed after the civil rights movement.

The most extreme white leader was Senator Ben Tillman of South Carolina. In 1900, he proudly said, "We have done our level best [to prevent blacks from voting] ... we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it." With no voting rights and no say in government, black people in the South faced a system of segregation and discrimination. Black and white people went to separate schools. Black people could not serve on juries. This meant they had little to no legal help. In Black Boy, Richard Wright wrote about being hit with a bottle and knocked from a moving truck for not calling a white man "sir." Between 1889 and 1922, the NAACP says that lynchings were at their worst. Almost 3,500 people, three-fourths of them black men, were murdered.

African Americans responded in two major ways: the Great Migration and the Civil Rights Movement.

The Great Migration began during World War I. It reached its peak during World War II. During this migration, black people left the racism and lack of opportunities in the South. They settled in northern cities like Chicago. There, they found work in factories and other jobs. This migration gave the black community a new sense of independence. It also helped create the lively black urban culture seen in the rise of jazz and the blues. These music styles spread from New Orleans north to Memphis and Chicago.

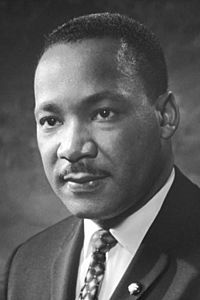

The migration also strengthened the growing civil rights movement. While the movement existed across the U.S. to fight Jim Crow laws, its main focus was on the Jim Crow laws in the South. Most major events in the movement happened in the South. These include the Montgomery bus boycott, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, the Selma to Montgomery marches, and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.. Also, some of the most important writings from the movement were written in the South, like King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail".

As a result of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, all Jim Crow laws across the South and elsewhere in the United States were removed. This change in the South's racial climate, along with new industries, helped bring in what is called the New South.

Changes in the Black Belt Farming System

Historians who study the South's economy often point out how the system of white supremacy and cotton plantations in the Black Belt continued for a long time. It lasted from the late colonial era until the mid-20th century, when it finally collapsed. Harold D. Woodman explains that outside forces caused this breakdown from the 1920s to the 1970s:

- When a significant change finally occurred, its impetus came from outside the South. Depression-bred New Deal reforms, war-induced demand for labor in the North, perfection of cotton-picking machinery, and civil rights legislation and court decisions finally... destroyed the plantation system, undermined landlord or merchant hegemony, diversified agriculture and transformed it from a labor- to a capital-intensive industry, and ended the legal and extra-legal support for racism. The discontinuity that war, invasion, military occupation, the confiscation of slave property, and state and national legislation failed to bring in the mid-19th century, finally arrived in the second third of the 20th century. A "second reconstruction" created a real New South.

The South and U.S. Foreign Policy

The South always had a strong interest in foreign affairs. This was especially true for expanding to the Southwest. And for the importance of foreign markets for Southern exports like cotton, tobacco, and oil. All Southern colonies supported the American Revolution. Virginia took a leading role. The South generally supported the War of 1812. This was very different from the strong opposition in the Northeast from Federalist Party members. Southern Democrats led the support for Texas annexation and the war with Mexico. Low tariffs (taxes on imports) were a priority, except for the sugar region of Louisiana. Throughout Southern history, exports were the main basis of the Southern economy. This started with tobacco, rice, and indigo in the colonial period. After 1800, cotton became the chief export of the United States. In the American Civil War, Confederate officials mistakenly thought Europe's need for cotton would force them to help the South. They believed "Cotton is King." Southerners thought their need for international markets required aggressive international foreign policies.

Woodrow Wilson, who was U.S. president from 1913–1921, had strong support from the South for his foreign policy regarding World War I and the League of Nations. In the 1930s, isolationism (staying out of world affairs) and "America First" attitudes were weakest in the South. Internationalism was strongest there. Southern Conservative Democrats opposed the domestic policies of the New Deal. But they strongly supported Franklin Roosevelt's international foreign policy during World War II. Historians have given various reasons for this. One is the region's strong military tradition. General George Marshall, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute, is famous for the Marshall Plan. This plan helped rebuild Europe after World War II. Instead of being against war, the South valued chivalry and honor. It was proud of its fighting ability and not bothered by violence. Virginia Senator Carter Glass said in May 1941: "Virginia has always been a leader in the vanguard of the fight for freedom. She is ready today as in the past to give virile leadership to the nation.” During the Vietnam War, some people from the South disagreed with the war, like J. William Fulbright (Arkansas) and Martin Luther King Jr. (Georgia). But Lyndon B. Johnson (Texas) and Secretary of State Dean Rusk (Georgia) supported it. The war was generally more supported in the South.

The South from Mid-20th Century to Today

In the years and decades after World War II, the old farming economy of the South changed. It became the "New South" – a manufacturing region with strong ties to laissez-faire capitalism (a system with little government interference in business). High-rise buildings began to appear in city skylines from the mid-to-late 20th century. Cities like Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, Houston, Memphis, Miami, Nashville, New Orleans, San Antonio, and Tampa saw these changes. The old main economic base, which focused largely on agriculture like cotton production, was phased out. This happened because of new mechanization technologies and the growth of new industries. There were 1.5 million cotton farms in 1945. Only 18,600 remained in 2009. By 2020, many Fortune 500 companies had their headquarters in the South. Texas had 50, Virginia 22, Georgia 18, Florida 18, North Carolina 13, and Tennessee 10. In 2022, Texas led the nation with 53 Fortune 500 company headquarters.

The industrialization and modernization of the South sped up after racial segregation policies ended in the 1960s. Today, the South's economy is a mix of agriculture, light and heavy industry, tourism, and high technology companies. These help both the national economy and the global economy. State governments in the South invited businesses to the "Sun Belt." They promised pleasant weather, fun activities, a lower cost of living, skilled workers, low taxes, weak labor unions, and a business-friendly environment. With more jobs in the South, people from other U.S. regions and immigrants from other countries moved there. This increased the population and political influence of Southern states. The newcomers and growing population helped replace the old rural political system. This system was built around small groups of powerful people in courthouse towns from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. Many suburban areas became the base of the growing Republican Party in the region. This party became dominant in presidential elections by 1968, and in most state politics by the 1990s.

As the economy grew into other job sectors during the mid-to-late 20th century, farming became less important. The remaining farmers often specialized in things like soybeans and cattle, or citrus in Florida. The need for cotton pickers largely ended with the use of machines. Almost all black cotton farmers moved to urban areas, either within the region or to cities in the North or Midwest. Former white farmers usually moved to nearby towns or cities within the region. The early to mid-20th century also saw many factories and service industries open in towns across the region. These provided new job opportunities.

During the 20th century, millions of non-Southern U.S. migrants and retirees moved south for job opportunities and mild winters. Often, they moved into homes near the coast. Over the years, this led to increasingly expensive hurricane damages. Tourism has also become a major industry. This is especially true in places like Williamsburg, Virginia, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, San Antonio, Texas, Orlando, Florida, and Branson, Missouri.

Aside from the still-unique weather, life in the South increasingly looks like a mix of cultures in many places. This is especially true in urban and metropolitan areas. Millions of non-southern U.S. migrants (especially in suburbs and coastal areas), including millions of Hispanics, along with many immigrants from different countries, have arrived. This has brought in different cultural values and social norms not rooted in Southern traditions. Observers believe that collective identity and Southern distinctiveness are decreasing. This is especially true when compared to "an earlier South that was somehow more authentic, real, more unified and distinct." However, the process has worked both ways. Aspects of Southern culture have spread throughout a larger part of the rest of the United States. This process is called "Southernization".

U.S. Presidents from the South

Throughout the history of the United States, many of the 45 people who have been U.S. president were from the South. Virginia was the birthplace of seven of the nation's first twelve presidents (including four of the first five).

This list includes members of the Whig Party, the Republican Party, and the Democratic Party. Also, Washington, while officially non-partisan, was generally linked with the Federalist Party.

Presidents born in the South and known for their connection to the region include:

- George Washington of Virginia (served 1789–1797)

- Thomas Jefferson of Virginia (served 1801–1809)

- James Madison of Virginia (served 1809–1817)

- James Monroe of Virginia (served 1817–1825)

- Andrew Jackson, born in either North Carolina or South Carolina, known for Tennessee (served 1829–1837)

- John Tyler of Virginia (served 1841–1845)

- James Knox Polk, born in North Carolina, known for Tennessee (served 1845–1849)

- Zachary Taylor of Virginia (served 1849–1850)

- Andrew Johnson, born in North Carolina, known for Tennessee (served 1865–1869)

- Lyndon Baines Johnson of Texas (served 1963–1969)

- Jimmy Carter of Georgia (served 1977–1981)

- Bill Clinton of Arkansas (served 1993–2001)

One president was born in the South and is known for both the South and elsewhere:

- Woodrow Wilson (served 1913–1921) was born and raised in the South. Although his academic and political career was in New Jersey, he still had strong ties to the South.

Presidents born outside the South, but generally known for their connection to the region:

- George H. W. Bush, born in Massachusetts, but spent his adult life in Texas (served 1989–1993)

- George W. Bush, born in Connecticut, lived from early childhood in Texas (served 2001–2009)

Presidents born in Southern states, but not mainly known for that region, include:

- William Henry Harrison, born in Virginia, known for Ohio (served 1841)

- Abraham Lincoln, born in Kentucky, moved at age 7; known for Illinois (served 1861–1865)

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, born in Texas, moved at age 2 and known for Kansas (served 1953–1961)