Foreign policy of the Woodrow Wilson administration facts for kids

The Foreign policy of the Woodrow Wilson administration covers how the United States interacted with other countries when Woodrow Wilson was President, from 1913 to 1921. Even though Wilson didn't have much experience in foreign policy, he made all the big decisions. He often got advice from his close friend, Edward M. House, who was called "The Colonel." Wilson followed the Democratic Party's ideas, which generally opposed war, taking over other countries, and getting involved in their problems. Instead, they wanted the U.S. to work with other nations for peace and freedom. Wilson chose William Jennings Bryan as his Secretary of State, who was a strong supporter of peace.

Contents

Leadership in Foreign Policy

President Wilson relied a lot on his friend, "Colonel" Edward M. House, for advice on foreign policy. Wilson later started to distrust House in 1919 and stopped talking to him.

After winning the 1912 election, Wilson needed a Secretary of State. William Jennings Bryan was a very important leader in the Democratic Party and helped Wilson get nominated. Wilson was a bit worried about Bryan's strong opinions and his independent ways. Bryan had traveled the world, giving speeches about peace and meeting leaders. Wilson, however, had less experience with international travel or diplomacy.

Bryan was helpful in passing important laws in the U.S. At first, he and Wilson worked well together on foreign policy. Bryan handled daily tasks, while Wilson made the big choices. Bryan also worked on 30 treaties with other countries. These treaties said that if countries had a disagreement, they would send it to a special group to investigate.

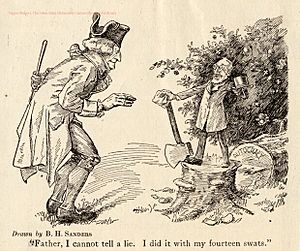

However, Bryan and Wilson disagreed about the U.S. staying neutral during World War I. Bryan resigned in June 1915. This happened after Wilson sent a strong message to Germany because a German submarine sank the British ship RMS Lusitania, killing 128 Americans. Bryan thought people traveled into war zones at their own risk. But Wilson believed it was wrong to sink a passenger ship without letting people get to lifeboats.

Wilson then chose Robert Lansing to replace Bryan. Lansing was good at routine work but didn't have many new ideas. This meant Wilson was completely free to make all major foreign policy decisions himself.

Lansing first supported being "kindly neutral" at the start of the war. But he changed his mind as Britain started interfering more with neutral ships. By mid-1915, Lansing strongly opposed Germany. He kept his views quiet because Wilson disagreed. Lansing worked to avoid conflict with Britain and to show the public Germany's bad actions.

The main ambassadors for the Allied powers were Cecil Spring Rice for Britain and Jean Jules Jusserand for France. Jusserand was very popular in the U.S. But Spring-Rice was friends with Wilson's political rivals, so Wilson didn't trust him. Colonel House helped by becoming friends with Sir William Wiseman, a British banker who handled money talks and spy operations. Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff was the German ambassador. He tried to get Berlin to accept Wilson's peace plans but failed. He also organized propaganda.

Latin America

The Panama Canal opened in 1914, right when World War I began. This canal was a long-time dream, allowing ships to travel quickly between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It helped trade and allowed the U.S. Navy to move warships faster. Britain and the U.S. agreed that all ships, including American ones, would pay the same tolls.

To further protect the Canal, the U.S. bought the Danish West Indies from Denmark in 1916 for $25 million. These islands were renamed the United States Virgin Islands. Most of the people living there were Black, and the economy was based on sugar.

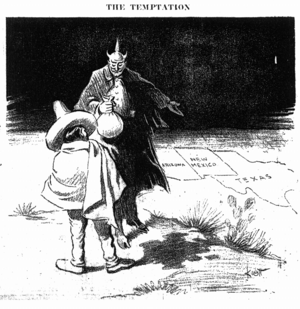

Mexico and the Revolution

The U.S. had long supported the dictator Porfirio Díaz in Mexico. When Díaz said he wouldn't run for president in 1910, it caused a lot of political excitement. Washington wanted the next president to continue Díaz's policies, which were good for American mining and oil businesses. But Díaz changed his mind, jailed a popular opponent, Francisco I. Madero, and ran again in a rigged election. This led to open rebellion.

Díaz resigned and left Mexico. After new elections, Madero won. At first, the U.S. was hopeful about Madero. But soon, the U.S. started working with his opponents. When Victoriano Huerta became president after Madero was killed, most countries recognized him, but Wilson refused. Wilson called Huerta's government a "government of butchers" and demanded democratic elections.

In April 1914, during the Tampico Affair, nine American sailors were briefly arrested by Huerta's soldiers. The local commander apologized, but refused to salute the U.S. flag or punish the officer who made the arrests. This led to the U.S. Navy seizing Veracruz. About 170 Mexican soldiers and many civilians were killed, along with 22 Americans.

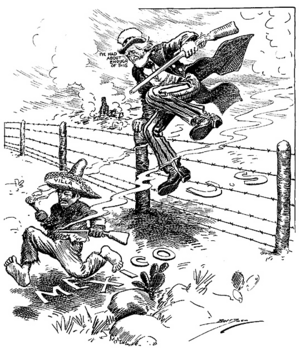

Pancho Villa was a local bandit who became a major leader in the fight against Huerta. For a time, Washington considered recognizing him as Mexico's leader. But Villa was defeated in 1915, and the U.S. supported another leader, Venustiano Carranza. Villa then raided a small U.S. border town, Columbus, New Mexico, killing 18 Americans. He hoped to start a war between Wilson and Carranza. Instead, Wilson sent General John J. Pershing and the Army on a limited mission into Mexico to catch Villa. They never caught him, and this angered many Mexicans. Wilson realized that rising tensions with Germany were more important, so he called the troops back in early 1917.

Meanwhile, Germany tried to distract the U.S. from Europe by starting a war. In January 1917, Germany sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram. It offered Mexico a military alliance to help them get back lands the U.S. had taken in the Mexican–American War. British spies caught the message and gave it to Washington. Wilson shared it with the press, which made Americans demand war against Germany. Mexico's government rejected the offer because its military knew they would lose a war with the U.S. Mexico stayed neutral and sold a lot of oil to Britain for its navy.

Nicaragua and U.S. Influence

Wilson wanted to help Latin American countries have democracy and stable governments. He also wanted fair economic policies. However, the situation in Nicaragua was often chaotic. Adolfo Díaz became president in 1911 and got loans from New York banks instead of European ones. When a rebellion started, he asked the U.S. for help, and Wilson agreed.

Nicaragua became a kind of protectorate under the 1916 Bryan–Chamorro Treaty. Nicaragua promised not to declare war, give away land, or borrow money from other countries without U.S. approval. It also allowed the U.S. to build a naval base and gave the U.S. the only right to build a canal across Nicaragua. The U.S. paid Nicaragua $3 million for this right, not planning to build a canal, but to make sure no other country could. The treaty was unpopular in the Caribbean but was followed until 1933. This treaty helped bring more political and financial stability to Nicaragua.

Asia

China and Japan's Demands

After the Xinhai Revolution ended the emperor's rule in China in 1911, the U.S. recognized the new Republic of China. But in reality, powerful regional leaders called warlords controlled much of the country.

In 1915, Japan secretly made the Twenty-One Demands to Yuan Shikai, China's president. These demands would greatly increase Japan's control over China. Japan wanted to keep the German areas it had taken in World War I. It also wanted more power in Manchuria and South Mongolia, and a bigger role in China's railways. The most extreme demands would have made China a Japanese protectorate, reducing Western influence. Japan was in a strong position because Western powers were busy fighting Germany.

Beijing made the secret demands public and asked Washington and London for help. The U.S. and Britain pressured Japan. In the final agreement in 1916, Japan dropped its most extreme demands. Japan gained a little in China but lost a lot of respect from the U.S. and Britain. The U.S. believed that a "strong and independent China" was important for its own interests in Asia.

Wilson was criticized for allowing Japan to take over German areas in Shandong at the Paris Peace Conference. However, some historians say Wilson was following treaties China had signed with Japan. Wilson tried to get Japan to promise to return the areas later, but China's representatives refused this compromise. This led to strong Chinese nationalism, like the May Fourth Movement, and some Chinese thinkers started looking to Russia for ideas.

Wilson was in touch with former students who were missionaries in China. He supported their work, believing that a "sleeping nation" like China could be awakened and contribute to the world's moral strength.

Japan and Land Laws

In 1913, California passed a law called the California Alien Land Law of 1913. This law stopped Japanese non-citizens from owning land in the state. Japan strongly protested, and Wilson sent Bryan to California to help. Bryan couldn't get California to change the law, and Wilson accepted it, even though it went against a 1911 treaty with Japan. This law caused anger in Japan that lasted for many years.

During World War I, both the U.S. and Japan fought on the Allied side. Japan's military took control of German bases in China and the Pacific. After the war in 1919, with U.S. approval, Japan was given control over the German islands north of the equator by the League of Nations. The U.S. did not want any such control.

Japan's aggressive actions toward China caused ongoing tension. This tension eventually led to World War II between the two nations. The U.S. was concerned about Japan's Twenty-One Demands on China in 1915. These demands would have given Japan control over former German areas and economic power in Manchuria, possibly making China a puppet state. The U.S. strongly opposed Japan's rejection of the Open Door Policy, which meant all countries should have equal trading rights in China. In 1915, the U.S. recognized Japan's "special interests" in some areas but worried about Japan taking over more of China.

In 1917, the Lansing–Ishii Agreement was made. U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing accepted that Japan had control in Manchuria, while it was still officially Chinese land. Japanese Foreign Minister Ishii Kikujiro agreed not to limit American business opportunities in other parts of China. Both sides also agreed not to use the war in Europe to gain more power in Asia.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan insisted on taking Germany's areas in China, especially in the Shandong Peninsula. President Wilson strongly opposed this but eventually gave in because Japan had a lot of support. This caused outrage in China and led to strong anti-Japanese feelings. The May Fourth Movement started as students demanded China's honor. In 1922, the U.S. helped find a solution. China got official control over Shandong, but Japan still had economic power there.

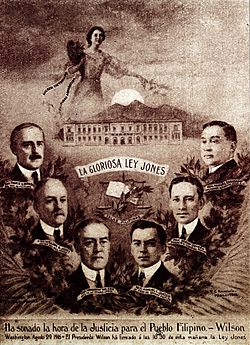

Philippines: Path to Independence

The Democratic Party in the U.S. had always opposed taking over the Philippines. They increasingly wanted the Philippines to be independent. Wilson himself had changed his mind and now wanted Filipinos to govern the islands until they became independent. He appointed Francis Burton Harrison as governor. Harrison replaced almost all American officials with Filipinos. By 1921, most government jobs were held by Filipinos.

Filipino leaders like Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña supported a bill in 1912 that would give the Philippines independence after eight years. But they later changed their minds. They wanted a bill that focused on the conditions for independence, not just a time limit. They feared that if they became independent too quickly without U.S. guarantees, Japan might take over.

The Jones Law, or Philippine Autonomy Act, was passed in 1916. Its introduction stated that the U.S. policy was to eventually give the Philippines independence, once a stable government was in place. The law kept an appointed governor-general but created a Philippine Legislature with two elected houses.

Filipino leaders paused their independence efforts during World War I to support the U.S. and the Allies. After the war, they pushed for independence again. In 1919, the Philippine Legislature declared its strong desire for freedom. They created a group to find ways to achieve independence. This group said the Jones Law was a promise from the U.S. to recognize Philippine independence once a stable government was formed. The American Governor-General Harrison agreed that a stable government was in place.

Russia and the Revolution

Wilson was hesitant, but he sent two groups of American soldiers into Russia. The American Expeditionary Force, Siberia was in Vladivostok, Russia, from 1918 to 1920. The other group, the American Expeditionary Force, North Russia, was part of a larger British and French effort in Northern Russia.

The Siberian force was supposed to help 40,000 Czechoslovak Legion soldiers. These soldiers were trying to travel across Russia to Vladivostok to join the Allies on the Western Front. The North Russia force aimed to stop the German army from taking Allied weapons that had been sent to Russia before Russia left the war. Neither force had an official combat mission. Some historians believe Wilson also wanted to oppose the Bolsheviks (the new communist government in Russia).

President Wilson believed that after the Russian emperor's rule ended, Russia would become a free-market democracy. He thought that getting involved against Soviet Russia would only turn the country against the U.S. In his Fourteen Points, he publicly said the U.S. should not interfere in the Russian Civil War. However, he did say that Russia's Polish territory should go to the newly independent Second Polish Republic.

Despite Wilson's views, the U.S. sent a small number of troops to Northern Russia and Siberia. This was partly due to fears of Japanese expansion into Russian territory and support for the Allied-aligned Czech Legion. The U.S. also sent indirect aid, like food and supplies, to the White Army, who were fighting against the Bolsheviks.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George suggested a meeting between the Bolsheviks and the White movement. They hoped to form a common Russian group for the conference. But the Soviet leaders, Leon Trotsky and Georgy Chicherin, had no intention of agreeing. They believed the conference was made up of old capitalist powers that would soon be overthrown by a world revolution.

By 1921, the Bolsheviks had won the Russian Civil War. They executed the royal family, refused to pay Russia's old debts, and called for a world revolution. Most of the world then saw Russia as a "pariah nation" (an outcast). Relations were also difficult because American companies wanted money for their businesses that the new Russian government had taken over.

After the war, there was a terrible famine in Russia and parts of Eastern Europe. A very large food relief effort, mostly in Russia, was funded by the U.S. government, charities, Britain, and France. The American Relief Administration, led by Herbert Hoover, provided much of this help.

Entry into World War I

Trying to Make Peace

From when the war started in 1914 until January 1917, Wilson's main goal was to use American neutrality to bring about a peace conference. For the first two years, neither side wanted to negotiate.

However, things changed in late 1916. Some historians argue that both sides were ready for peace talks if Wilson would lead them. But Wilson waited too long. He didn't fully understand how much financial power he had over Britain. He also relied too much on Colonel House and Secretary of State Robert Lansing, who sometimes made his plans harder by encouraging Britain to delay. Some believe that when Wilson finally made his peace proposal in January 1917, it was too late. Instead of peace, the war got worse. German military leaders convinced their emperor that they could win by using unrestricted submarine warfare and moving troops from the Russian front to attack the French and British.

Wilson decided to enter the war in April 1917, more than two and a half years after it began. The main reasons were Germany's submarine attacks on American ships carrying supplies to Britain. Wilson also wanted to make the world safe for democracy. He believed war was needed because Germany threatened American ideals of democracy and peace with its militarism. It also threatened American trade and rights as a neutral country. By April 1917, most Americans, leaders, and members of Congress strongly supported Wilson. The U.S. acted independently and did not form a formal alliance with Britain or France.

German Submarine Warfare

When World War I began in August 1914, the U.S. declared neutrality. It wanted to help make peace. The U.S. insisted on its rights as a neutral country, which meant American companies and banks could sell supplies or lend money to either side. But because Britain had a strong naval blockade, almost no sales or loans went to Germany, only to the Allies.

Americans were shocked by the German army's cruel actions against civilians in Belgium. Many Americans, especially those with British heritage, favored Britain. Former President Theodore Roosevelt strongly pushed for war, criticizing Wilson for being too timid. Wilson insisted on neutrality, criticizing both British and German violations. The British seized American property, but the Germans took American lives.

In 1915, a German U-boat (submarine) torpedoed the unarmed British passenger ship RMS Lusitania. It sank in 20 minutes, killing 128 American civilians and over 1,000 Britons. This was against the rules of war, which said passenger ships should not be sunk without giving people a chance to get to lifeboats. American opinion turned strongly against Germany, seeing it as a threat to civilization. Germany apologized and promised to stop U-boat attacks. Both sides rejected Wilson's repeated attempts to negotiate an end to the war.

Germany changed its mind in early 1917. It saw a chance to cut off Britain's food supply by using unrestricted submarine warfare again. The German leaders knew this would mean war with the U.S. But they expected to defeat the Allies before America could send many troops. Germany started sinking American merchant ships in early 1917. Wilson asked Congress to declare war in April 1917. He convinced those against the war by saying it was a war to end aggressive militarism and make the world "safe for democracy."

Public Opinion and Economy

From 1914 to 1916, most Americans wanted to stay out of the war. Neutrality was especially strong among Irish Americans, German Americans, Scandinavian Americans, church leaders, women, and white Southerners. During the war, most Americans came to see Germany as the aggressor in Europe and an enemy of world peace.

While the U.S. was at peace, American banks lent huge amounts of money to the Allied powers. This money was mostly used to buy weapons, raw materials, and food from the U.S. Wilson made few preparations for the army before 1917. But he did approve a massive shipbuilding program for the United States Navy. Wilson was re-elected in 1916 on a platform of keeping the U.S. out of war.

By 1917, Germany seemed to be winning in Europe. Belgium and Northern France were occupied, Russia was leaving the war, and the remaining Allied nations were running out of money. However, Britain's economic blockade was causing shortages of fuel and food in Germany. So, Germany decided to restart unrestricted submarine warfare. The goal was to stop supplies from reaching Britain, even though German leaders knew sinking American ships would likely bring the U.S. into the war.

Germany's Zimmermann Telegram angered Americans just as German submarines began sinking American merchant ships. Wilson asked Congress for "a war to end all wars" that would "make the world safe for democracy." Congress voted to declare war on Germany on April 6, 1917. The U.S. immediately sent money and supplies, and a small military force. American troops began major fighting on the Western Front in the summer of 1918, arriving at a rate of 10,000 soldiers a day.

War with Austria-Hungary

The U.S. Senate voted 74 to 0 to declare war on Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917. They cited Austria-Hungary breaking off relations with the U.S., its use of unrestricted submarine warfare, and its alliance with Germany. The House of Representatives also passed the declaration. The U.S. never declared war on Germany's other allies, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria.

The Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles

The Paris Peace Conference started in January 1919 in Paris, France. Its goal was to decide the terms of peace after World War I. Nearly thirty nations took part, but the main decisions were made by the "Big Four": Great Britain, France, the United States, and Italy. Italy later left, leaving the "Big Three": Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and French Premier Georges Clemenceau. They led the talks and wrote the Treaty of Versailles to end the war with Germany.

The Treaty of Versailles included the plan for the League of Nations. This would be an international group for discussions and for keeping peace. Wilson focused on creating the League. Clemenceau wanted to make Germany permanently weak. Lloyd George tried to find compromises between them.

Many Europeans welcomed Wilson warmly at first. They saw him as a possible savior from the old system and a builder of a fairer world. But this feeling didn't last. European leaders soon disliked Wilson's constant moralizing and his lack of understanding of Europe's problems. They also found him stubborn. By the end of the conference, many in Europe and even some Americans were tired of Wilson.

Treaty of Versailles Details

Negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference were complicated. Great Britain, France, and Italy fought as the Allied Powers. The U.S. joined the war in 1917 as an "Associated Power." This meant the U.S. fought alongside the Allies but was not bound by their earlier secret agreements. These secret agreements were about dividing territories after the war. President Wilson strongly opposed many of these plans, like Italy's demands for land in the Adriatic Sea. This often caused big disagreements among the "Big Four." Wilson strongly opposed Italy's demand for control of Fiume, and with British and French support, the Italian group left the conference.

The negotiations were also difficult because important nations were missing. The defeated Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria) were not allowed to attend. Russia had fought with the Allies until December 1917, when its new Bolshevik government left the war. The Bolsheviks refused to pay Russia's old debts to the Allies and published secret agreements between the Allies, which angered them. The "Big Four" refused to recognize the new government in Moscow and did not invite its representatives to the Peace Conference.

Following French and British wishes, the Treaty of Versailles placed strict punishments on Germany. Germany had to give up about 10% of its land in Europe and all of its colonies. The city of Danzig and the coal-rich Saarland were placed under the control of the League of Nations. France was allowed to use the Saarland's economic resources until 1935. The German Army and Navy were limited in size. The Treaty also said that Kaiser Wilhelm II and other high-ranking German officials could be tried as war criminals.

Under Article 231 of the Treaty, Germany accepted responsibility for starting the war and agreed to pay financial payments to the Allies. The amount was set at 132 billion gold Reichsmark (about $32 billion U.S. dollars at the time), on top of an initial $5 billion payment. Germans grew to resent these harsh conditions.

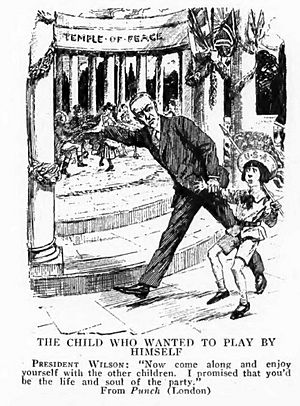

Senate Rejection of the Treaty

Even though the Treaty of Versailles didn't please everyone, when President Woodrow Wilson returned to the U.S. in July 1919, most Americans probably supported it, including the League of Nations. But the Senate needed a two-thirds majority to approve the Treaty. The Senate voted on several versions but never approved any.

The main opposition focused on Article 10 of the Treaty, which dealt with collective security and the League of Nations. Opponents argued that this article would give the League's Council power over the U.S. government's ability to declare war. The opposition came from two groups:

- The "Irreconcilables" refused to join the League of Nations under any circumstances.

- The "Reservationists," led by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, wanted changes made before they would approve the Treaty.

Lodge tried to pass amendments, which failed. But he did manage to add 14 "reservations" (conditions) to the Treaty in November. In a final vote on March 19, 1920, the Treaty of Versailles failed to be approved by seven votes. As a result, the U.S. government signed a separate peace treaty with Germany, the Treaty of Berlin, on August 25, 1921. This treaty said the U.S. would get all the "rights, privileges, and payments" from the Treaty of Versailles, but it did not mention the League of Nations, which the U.S. never joined.

Wilson's Ideals: Wilsonianism

Wilson was a deeply religious man who believed in serving others. His ideas about international relations are called "Wilsonianism." This idea suggests that the U.S. should get involved in the world to fight for democracy. It has been a debated idea in American foreign policy ever since.

Missionary Diplomacy

Missionary diplomacy was Wilson's belief that the U.S. had a moral duty to not recognize any Latin American government that wasn't democratic. This was an expansion of President James Monroe's 1823 Monroe Doctrine.

Fourteen Points for Peace

The Fourteen Points were Wilson's ideas for peace negotiations to end the war. He presented these principles in a speech to Congress on January 8, 1918. By October 1918, the new German government was negotiating peace based on these points. However, his main Allied partners (Georges Clemenceau of France and David Lloyd George of Great Britain) were doubtful about how well Wilson's ideals would work.

Wilson called for:

- Ending secret treaties.

- Reducing weapons.

- Adjusting colonial claims to be fair to both native peoples and colonists.

- Freedom for ships to travel anywhere on the seas.

Wilson also suggested ways to ensure future world peace. For example, he proposed removing economic barriers between nations and allowing self-determination for national minorities (meaning groups of people could decide their own future). Most importantly, his Fourteenth Point was about creating a world organization that would protect the "political independence and territory of great and small states alike"—a League of Nations. In his tough talks with Clemenceau and Lloyd George, he was willing to compromise on some points, but he always insisted on keeping the League.

Principles of Wilsonianism

The main ideas linked to "Wilsonianism" include:

- Creating groups and meetings to solve conflicts, especially the League of Nations and later the United Nations.

- Supporting the spread of democracy. Wilson hoped democracy would come from self-determination, but he didn't aim to directly force democracy on other nations.

- Emphasizing self-determination for different peoples.

- Supporting the spread of capitalism.

- Supporting collective security (nations working together to protect each other) and opposing American isolationism (staying out of world affairs).

- Supporting multilateralism (nations working together through discussion).

- Supporting open diplomacy and opposing secret treaties.

- Supporting freedom of navigation and freedom of the seas.

Impact of Wilsonianism

Historians say that American foreign relations since 1914 have been based on Wilson's ideals. His ideas still influence American foreign policy today.

Wilson was a very good writer and thinker, and his diplomatic ideas had a big impact on the world. Diplomatic historian Walter Russell Mead explained that Wilson's principles are still important in European politics today: self-determination, democratic government, collective security, international law, and a league of nations. Even though Wilson didn't get everything he wanted at Versailles, and the U.S. Senate never approved his treaty, his vision set the tone for the 20th century. What was once seen as just a dream is now accepted as fundamental. This was a great achievement, and no European leader of the 20th century had such a lasting and positive influence.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |