Frederick Law Olmsted facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

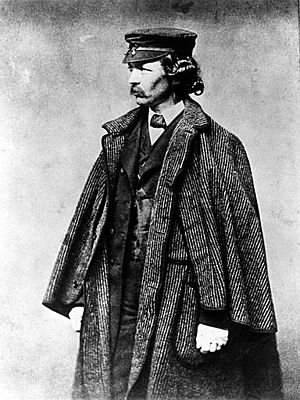

Frederick Law Olmsted

|

|

|---|---|

Olmstead in 1893;

engraving after a photograph |

|

| Born | April 26, 1822 Hartford, Connecticut, U.S.

|

| Died | August 28, 1903 (aged 81) Belmont, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Old North Cemetery, Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Landscape architect |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Cleveland Perkins |

| Children | John Charles, Charlotte, Owen, and Marion, and Frederick Law Jr. |

| Parent(s) | John and Charlotte Olmsted |

| Signature | |

Frederick Law Olmsted (born April 26, 1822 – died August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect. He was also a journalist and a public administrator. Many people consider him the "father of landscape architecture" in the United States.

Olmsted became famous for designing many well-known city parks. He often worked with his partner, Calvert Vaux. Their first big project was Central Park in New York City. This success led them to design many other parks, like Prospect Park in Brooklyn.

Olmsted worked on many other important projects across the country. These include the first public park system in Buffalo, New York. He also helped create Niagara Reservation in Niagara Falls, New York. This is the oldest state park in the U.S. He also designed parts of the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. He even helped plan the campuses for major universities like the University of California, Berkeley and Stanford University.

His work was highly respected by people at the time. His designs, especially in Central Park, set a high standard for landscape architecture. He was also an early supporter of the conservation movement. This movement aims to protect natural areas. He worked to save places like Niagara Falls and the Adirondack Mountains. During the American Civil War, he played a big role in organizing medical services for the Union Army.

Frederick Olmsted's Early Life and Education

Frederick Olmsted was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on April 26, 1822. His father, John Olmsted, was a successful merchant who loved nature and travel. Frederick and his younger brother, John Hull, shared this interest. His mother, Charlotte Law (Hull) Olmsted, passed away before he turned four. His father remarried in 1827 to Mary Ann Bull, who also loved nature.

When Frederick was almost ready for Yale College, his eyes became weak from sumac poisoning. Because of this, he had to give up his college plans. He then worked as a sailor, a merchant, and a journalist. In 1848, he settled on a 125-acre farm on Staten Island. His father helped him buy this farm. The house where Olmsted lived on the farm is still standing today.

Marriage and Family Life

On June 13, 1859, Olmsted married Mary Cleveland (Perkins) Olmsted. Mary was the widow of his brother John, who had died in 1857. He adopted her three children, who were his nephews and niece. These children were John Charles Olmsted (born 1852), Charlotte Olmsted, and Owen Olmsted.

Frederick and Mary also had two children together who lived past infancy. They had a daughter named Marion (born 1861) and a son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., born in 1870.

Frederick Olmsted's Career

Starting as a Journalist

Olmsted had an important career in journalism. In 1850, he traveled to England to see public gardens. He was very impressed by Joseph Paxton's Birkenhead Park. After this trip, he wrote a book called Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England in 1852. This book helped him get more writing jobs. His visit to Birkenhead Park later inspired his ideas for Central Park in New York City.

He was very interested in the slave economy in the American South. The New York Daily Times (now The New York Times) asked him to travel through the American South and Texas. He made this research journey from 1852 to 1857. His reports to the Times were later put into three books.

These books are seen as clear, firsthand accounts of the South before the Civil War. Olmsted argued that slavery made the Southern states inefficient. He believed it also made them fall behind economically and socially. He thought that only a small number of large plantation owners truly benefited from slavery. He noted that the lack of a middle class and the poverty of many white people in the South prevented the growth of many public services. These services were common in the North.

Between his travels, Olmsted worked as an editor for Putnam's Magazine. He also supported and sometimes wrote for the magazine The Nation, which started in 1865.

Designing New York City's Central Park

Andrew Jackson Downing, a landscape architect, was one of the first to suggest building Central Park in New York City. Downing was a friend and mentor to Olmsted. He introduced Olmsted to Calvert Vaux, an architect from England. After Downing died in 1852, Olmsted and Vaux decided to enter the Central Park design competition together. Vaux asked Olmsted to join him because he was impressed with Olmsted's ideas and connections. Before this, Olmsted had never designed a landscape.

Their design, called the Greensward Plan, was chosen as the winner in 1858. Olmsted began working on the plan almost right away. Olmsted and Vaux continued to work together on other projects. They designed Prospect Park in Brooklyn from 1865 to 1873.

Olmsted believed that public green spaces should be open to everyone. He thought they should be protected from private ownership. This idea is now a basic part of what a "public park" means. But back then, it was a new idea. Olmsted worked hard to keep this principle alive during his time as a Central Park commissioner.

Leading the Sanitary Commission

In 1861, Olmsted took a break from Central Park. He went to Washington, D.C., to work as the Executive Secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. This group was like an early version of the Red Cross. He helped care for wounded soldiers during the American Civil War. In 1862, he led the medical efforts for sick and wounded soldiers during the Union General McClellan's Peninsula Campaign.

Olmsted worked very hard for the Sanitary Commission. He wanted to control all parts of the work and refused to let others help. This led him to work too much and become very tired. By January 1863, he was often irritable. He resigned on September 1, 1863, because of exhaustion and losing support. However, within a month, he was on his way to California.

Gold Mining in California

In 1863, Olmsted moved west to manage a new gold mining estate. This was the Rancho Las Mariposas-Mariposa estate in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California. The mine was not successful. By 1865, the company went bankrupt, and Olmsted returned to New York.

In 1865, Olmsted was chosen to be on the first board of commissioners. This board managed the new Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove land grants.

Becoming a U.S. Park Designer

In 1865, Vaux and Olmsted formed a company called Olmsted, Vaux & Co. When Olmsted returned to New York, they designed Prospect Park. They also planned parks for suburban Riverside, near Chicago. Other projects included the park system for Buffalo, New York. They also designed Milwaukee, Wisconsin's large system of parks. They worked on the Niagara Reservation at Niagara Falls and Belle Isle in Detroit.

Olmsted did not just create single city parks. He also thought of entire systems of parks. These systems included connecting parkways to link cities to green spaces. Some of his best large-scale projects include the park systems for Buffalo, New York, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Louisville, Kentucky. The Louisville system was one of only four complete park systems designed by Olmsted in the world.

Olmsted often worked with architect Henry Hobson Richardson. He designed the landscapes for many of Richardson's projects. In 1871, Olmsted designed the grounds for the Hudson River State Hospital for the Insane in Poughkeepsie.

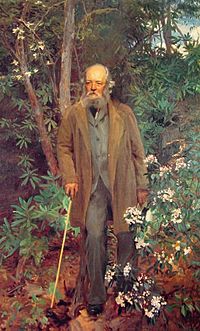

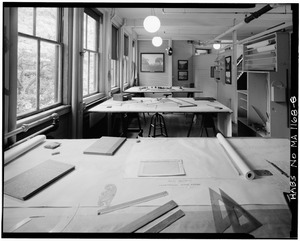

In 1883, Olmsted started what is thought to be the first full-time landscape architecture firm. It was in Brookline, Massachusetts. He called his home and office Fairsted. Today, it is the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. From there, Olmsted designed Boston's Emerald Necklace. He also planned the campuses of Wellesley College, Smith College, Stanford University, and the University of Chicago. He also designed the grounds for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago.

A Leader in Conservation

Olmsted was an important early leader in the conservation movement in the United States. He knew a lot about California. He was likely one of the people who suggested that Congress set aside Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove as public lands. This was the first time Congress set aside land for public use. Olmsted served on the board that managed this state reserve for one year. His 1865 report to Congress explained why the government should protect public lands. He said their value was for future generations.

In the 1880s, he worked to protect the natural beauty of Niagara Falls. Factories building electrical power plants were threatening the falls. At the same time, he worked to save the Adirondack region in upstate New York. He was also one of the people who helped start the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1898.

Olmsted sometimes refused to design parks if he felt it would harm nature. In 1891, he would not create a plan for Presque Isle Park in Marquette, Michigan. He said it "should not be marred by the intrusion of artificial objects."

Later Life and Legacy

In 1895, health issues forced Olmsted to retire. By 1898, he moved to Belmont, Massachusetts. He became a patient at the McLean Hospital. He had once submitted a design for the hospital's grounds, but it was never built. He stayed there until he passed away in 1903. He was buried in the Old North Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.

After Olmsted retired and passed away, his sons John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. continued his work. Their company was called the Olmsted Brothers. The firm continued until 1980. Many projects done by the Olmsted sons are sometimes mistakenly credited to Frederick Law Olmsted today. For example, the Olmsted Brothers firm made a park plan for Portland, Maine, in 1905. This plan created connecting parkways between existing parks.

A residence hall at the University of Hartford was named in his honor. Olmsted Point, in Yosemite National Park, was named after Olmsted and his son Frederick.

Frederick Olmsted is known as the "father of American Landscape Architecture."

Olmsted's Design Principles

Olmsted was inspired by English landscape and garden design. He believed in designing spaces that used the natural features of an area. He called this the "genius" of the place. He also thought that small details should not stand out too much. Instead, they should work together to make the whole space better. He wanted his designs to feel natural and not draw attention to themselves. The goal was for the design to make people feel relaxed without them even realizing why. Usefulness was more important than just decoration. Every part, like a bridge, a path, or a tree, was chosen to create a specific feeling.

Olmsted mainly used two styles: pastoral and picturesque. Each style had a different effect. The pastoral style used large green areas with small lakes, trees, and groves. This style made people feel calm and refreshed. The picturesque style used rocky, uneven land with many shrubs and climbing plants. This style showed the richness of nature. The picturesque style also used light and shadow to make the landscape feel a bit mysterious.

He designed scenery to make the space feel bigger. He used plants and trees to create soft, unclear boundaries instead of sharp ones. He also played with light and shadow up close and blurred details farther away. For example, he might have a large green area ending in a group of yellow poplar trees. Or a path that winds through the landscape and crosses other paths, creating new views.

The idea of "subordination" meant that all objects and features served the overall design. This can be seen in how he used native plants throughout a park. Planting non-native species just because they were unique was seen as going against the design's purpose. Their uniqueness would draw too much attention, and the goal was to help people relax. Usefulness was always the main goal. "Separation" meant keeping different styles and uses of areas apart. This made the park safer and less distracting.

A great example of these ideas is the Central Park Mall. This is a large walkway leading to the Bethesda Terrace. It is the only formal part of Olmsted and Vaux's original natural design. The designers said a "grand promenade" was a "key part of a city park." Even though it was formal, its style was meant to blend in with the natural views around it. Wealthy visitors could get out of their carriages at one end. Their carriages would then drive around to the Terrace to pick them up later. The Promenade was lined with elm trees and offered views of Sheep Meadow.

Rich New Yorkers, who often did not walk much in the park, mixed with less wealthy people in the Terrace areas. Everyone could enjoy a break from the busy city. However, the wealthiest people also hired Olmsted's firm to design their private country estates. An example is the estate of Frederick T. van Beuren Jr. in New Jersey.

See also

In Spanish: Frederick Law Olmsted para niños

In Spanish: Frederick Law Olmsted para niños

- List of Olmsted works

- Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

- Landscape designer

- History of gardening

|