History of gardening facts for kids

The story of gardening is closely linked to the story of farming. For a long time, beautiful gardens were mostly for rich people. Smaller gardens usually focused on growing food, like a kitchen garden, which is still common today.

Since ancient times, some main types of gardens have been popular. These include gardens from the Ancient Near East (which led to the Islamic garden), Mediterranean gardens (like the Roman garden that influenced Europe a lot), and the Chinese garden (which inspired the Japanese garden). People learned basic gardening skills through trial and error. But the plants available have changed a lot, especially recently. Many new plants have come from other parts of the world. Today, most ornamental plants (plants grown for beauty) are special types called cultivars. These are bred to have better colors, longer blooms, bigger sizes, or to be tougher.

In Europe during the Renaissance, the Italian garden style was very popular. This then led to the French formal garden during the Baroque period. Both styles were very neat and organized, like outdoor buildings. In the 1700s, the English landscape garden became popular. These looked natural and wild, but they needed huge spaces. By the end of that century, this style was used for most big new gardens across Europe.

Gardening can be seen as a way to show beauty through art and nature. It can also show a person's or culture's style, their ideas about life, or even their wealth or national pride in both private and public spaces.

Contents

- How Gardens Began and Grew

- Exploring Garden Styles Through History

- Mesopotamian Gardens: The Land Between Rivers

- Gardens of the Indian Subcontinent

- Persian Gardens: Oasis in the Desert

- Egyptian Gardens: Beauty and Usefulness

- Greek and Roman Gardens

- Chinese and Japanese Gardens: Nature's Art

- European Gardens: From Monasteries to Mansions

- Byzantine Gardens: A Blend of Cultures

- Medieval Gardens: Monasteries and Utility

- The Renaissance: A New Era for Gardens

- French Baroque: Grand and Formal Gardens

- Mediterranean Gardens: Fruitfulness and Frugality

- English Landscape Gardens: Natural Beauty

- Gardenesque Gardens: Showing Off Plants

- Wild Gardens and Herbaceous Borders: Natural and Colorful

- Mesoamerican Gardens: Ancient American Traditions

- Contemporary Gardens: Modern and Sustainable

- Famous Gardeners in History

- Famous Historic Gardens Around the World

- Images for kids

- See also

How Gardens Began and Grew

Gardens probably started around 10,000 BC when people first built fences or barriers. These barriers were likely used to keep out animals and unwanted visitors. This idea might have begun in West Asia and then spread to other parts of Asia, Greece, and Europe. The words "garden" and "yard" come from an old English word, "geard," which means a fence or enclosed area.

After the first civilizations appeared, rich people began making gardens just for beauty. Old Egyptian paintings from the 1500s BC show some of the earliest evidence of beautiful gardens. They show lotus ponds with neat rows of acacia and palm trees. Another old tradition comes from Persia. Darius the Great was said to have a "paradise garden." The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were famous as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Persian gardens were designed with a main line of symmetry, meaning they were balanced on both sides.

Persian garden ideas spread to Hellenistic Greece after Alexander the Great. Around 350 BC, there were gardens at the Platonic Academy in Athens. Theophrastus, who wrote about plants, supposedly got a garden from Aristotle. Epicurus had a garden where he walked and taught. He even left it to his friend Hermarchus. Other writers like Alciphron also wrote about private gardens.

The most important ancient gardens in the Western world were those of Ptolemy in Alexandria, Egypt, and the gardening ideas that Lucullus brought to Rome. Old wall paintings in Pompeii, Italy, show how fancy gardens became later. The richest Romans built huge villa gardens with water features like fountains and small rivers. They also had topiary (plants shaped into designs), roses, and shady walkways. You can still see evidence of these gardens at places like Hadrian's Villa.

Vitruvius, a Roman writer and engineer, wrote the oldest design book in 27 BC. His book, Ten Books on Architecture, covered design ideas, landscape planning, and public projects like parks. Vitruvius believed that good design needed to be strong, useful, and beautiful. Many still think these ideas are key to good landscape design today.

After the fall of Rome around 400 AD, Byzantium and Moorish Spain kept gardening traditions alive. Around this time, a different gardening style grew in China. This style then went to Japan, where it became fancy gardens with tiny, natural-looking landscapes around ponds. Japan also developed the simple Zen garden style found at temples.

In Europe, gardening became popular again in France in the 1200s. When people rediscovered old Roman villa and garden descriptions, a new type of garden, the Italian Renaissance garden, was created in the late 1400s and early 1500s. The Spanish Crown built the first public parks of this time in the 1500s, both in Europe and the Americas. The formal garden à la française, like the famous Gardens of Versailles, was the main garden style in Europe until the mid-1700s. Then, the English landscape garden and French landscape garden became more popular. In the 1800s, many old styles came back, along with romantic, cottage-inspired gardening.

In England, William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll were important. Robinson liked "wild" gardens, and Jekyll liked perennial gardens (plants that come back every year). Andrew Jackson Downing and Frederick Law Olmsted brought European styles to North America. They especially influenced the design of public parks, college campuses, and suburban areas. Olmsted's ideas were important well into the 1900s.

The 1900s saw modern ideas in gardens. Designers like Thomas Church used clear, simple lines. Brazilian Roberto Burle Marx used bold colors and shapes. Today, people are more aware of the environment. Sustainable design practices, like green roofs and rainwater harvesting, are becoming common as new ideas develop.

Exploring Garden Styles Through History

Mesopotamian Gardens: The Land Between Rivers

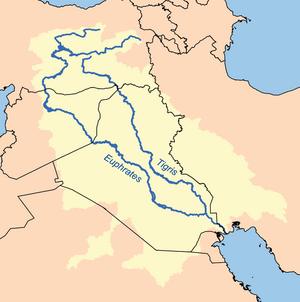

Mesopotamia was a land between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. It had hills in the north and flat plains in the south. People like the Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians lived there from about 3,000 BC. We know about their gardens from old writings, pictures, and archaeological digs. In Western stories, Mesopotamia is where the Garden of Eden was located, and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Temple gardens started as sacred groves. Kings also had several types of royal gardens.

The courtyard garden was inside palace walls. On a larger scale, it was a cultivated area inside city walls. At Mari (around 1,800 BC), one huge palace courtyard was called the Court of the Palms. It had raised walkways of baked brick where the king would eat. At Ugarit (around 1,400 BC), there was a stone water basin. The main feature was likely a tree, like a date palm or tamarisk. A sculpture from the 600s BC shows Assyrian king Assurbanipal feasting with his queen under a vine arbor.

Kings also created large royal hunting parks to keep exotic animals and plants they collected from other lands. King Tiglath-Pileser I (around 1,000 BC) listed many animals like horses, deer, and gazelles. He boasted, "I counted them like flocks of sheep."

Around 1,000 BC, Assyrian kings developed a style of city garden. These gardens looked natural and had running water from rivers. They also featured exotic plants from foreign trips. Assurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) listed many trees like pines, cypresses, almonds, and pomegranates. He said, "The canal water gushes from above into the gardens; fragrance fills the walkways." The city garden became most grand with the palace design of Sennacherib (704–681 BC). His water system stretched for 50 km into the hills. He called his palace and garden "a wonder for all peoples."

The Bible's Book of Genesis mentions the Tigris and Euphrates as two rivers of the Garden of Eden. No exact place has been found, but many ideas exist.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon are listed by ancient Greek writers as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. But digs in Babylon haven't found clear proof, so some scholars think they might be a legend. Or, the story might have come from Sennacherib's garden in Nineveh.

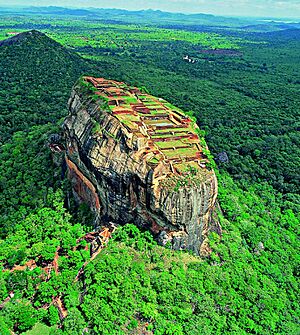

Gardens of the Indian Subcontinent

Gardens in the Indian subcontinent are mentioned in old writings. These texts describe different types of gardens and how to build them. Archaeologists have found the gardens at Sigiriya in Sri Lanka. They are the best-preserved water gardens in South Asia and one of the oldest landscaped gardens in the world.

Indian Gardens: Ancient Designs

Ancient Indian gardens appear in old Hindu texts like Rigveda and Ramayana. Buddhist stories mention a bamboo grove given by King Bimbisara to Buddha. Another Buddhist text, Digha Nikaya, says Buddha stayed in a mango orchard given by a doctor named Jivaka. The Sanskrit word Arama means garden. A sangharama was a garden-like place where Buddhist monks lived. In Buddha's time, Vaishali was a rich city full of parks and gardens. Emperor Ashoka's writings mention botanical gardens for medicinal plants and trees. These gardens had pools, were laid out in grids, and often had chattri pavilions.

Old India had four kinds of gardens: udyan, paramadodvana, vrikshavatika, and nandanavana. A Vatika was a small garden inside homes. Margeshu vriksha was the practice of planting trees along roads for shade.

The Manasollasa, a 12th-century book about garden design, says gardens should have rocks and raised mounds. They should be shaped with different plants and trees, artificial ponds, and flowing streams. It describes how to arrange plants, prepare soil, and fertilize. It also tells when to plant, how to water, and how to protect the garden. Public parks and woodland gardens are described, with about 40 types of trees suggested for parks.

In medieval India, courtyard gardens were also key parts of Mughal and Rajput palaces.

The Indian text Shilparatna (1500s AD) says a flower garden or public park should be in the northern part of a town. According to Kalidasa, a garden was carefully designed with tanks, vine arbors, seats, mock hills, and swings. Arthashastra and other texts mention public gardens outside towns. People would go there for picnics. Upavan Vinoda in the Sharngadhara-paddhati (1300s AD) is a whole chapter on horticulture and gardening. Indian gardens were also built around large water reservoirs or tanks, often along rivers.

Sri Lankan Gardens: Ancient Water Features

The water gardens of Sigiriya are in the middle of the western area. There are three main gardens here. The first garden is a plot surrounded by water. It connects to the main area with four walkways, each with a gate. This garden follows an old design called char bagh, and it's one of the oldest examples of this style still around.

The second garden has two long, deep pools on either side of the path. Two shallow, winding streams lead to these pools. Fountains made of round limestone plates are here. Underground water pipes supply water to these fountains, and they still work, especially in the rainy season. Two large islands are on either side of this garden. Summer palaces were built on the flat tops of these islands. Two more islands are further north and south, built like the first garden's island.

The third garden is higher than the other two. It has a large, eight-sided pool with a raised platform in its northeast corner. The big brick and stone wall of the fortress is on the eastern edge of this garden.

The water gardens are built symmetrically on an east-west line. They connect to the outer moat on the west and a large artificial lake to the south of the Sigiriya rock. All the pools are also linked by an underground pipe system fed by the lake and connected to the moats. A tiny water garden is west of the first water garden. It has several small pools and waterways. This smaller garden was found recently and seems to have been built after the Kashyapan period, perhaps between the 900s and 1200s.

Persian Gardens: Oasis in the Desert

All Persian gardens, from ancient times to later periods, were created to stand out from the dry landscape of the Iranian Plateau. Unlike European gardens, which seemed to be shaped from existing land, Persian gardens looked like impossible oases. Their delicate beauty showed how much they contrasted with the harsh environment. Trees and trellises provided shade. Pavilions and walls were also important for blocking the sun.

Because of the heat, water was very important for both designing and maintaining the garden. Irrigation was often needed. Water might come through a tunnel called a qanat, which brought water from an underground source. Well-like structures connected to the qanat allowed water to be drawn up. Sometimes, an animal-powered Persian well would bring water to the surface. These wheel systems also moved water around surface channels, like those in the chahar bāgh style. Trees were often planted in a ditch called a juy. This stopped water from evaporating and helped water reach the tree roots quickly.

The Persian style often tried to connect indoors with outdoors. This was done by linking a surrounding garden with an inner courtyard. Designers often used architectural parts like arched doorways between outer and inner areas to open up the space.

Egyptian Gardens: Beauty and Usefulness

Gardens were highly valued in ancient Egypt. They were kept for everyday use and also attached to temples. Gardens in private homes and villas before the New Kingdom were mostly for growing vegetables. They were usually near a canal or the river. However, in the New Kingdom, gardens were often surrounded by walls. Their purpose then included pleasure and beauty, as well as growing food.

Garden produce was a big part of food, but flowers were also grown. They were used in garlands for parties and for medicine. While poor people had small patches for vegetables, rich people could afford gardens with shady trees and decorative pools with fish and waterfowl. There might be wooden structures forming pergolas to support grapevines, used for raisins and wine. There could even be fancy stone kiosks just for decoration, with statues.

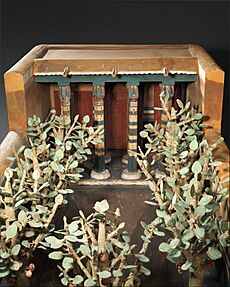

Temple gardens had plots for special vegetables, plants, or herbs. These were considered sacred to a certain god and were needed for rituals and offerings, like lettuce for Min. Sacred groves and ornamental trees were planted in front of or near both cult temples and burial temples. Temples were seen as representations of heaven and the actual home of a god. So, gardens were laid out with this in mind. Paths leading to the entrance might be lined with trees. Courtyards could have small gardens. Between temple buildings, gardens with trees, vineyards, flowers, and ponds were kept.

An ancient Egyptian garden would have looked different from a modern one. It might have seemed more like a collection of herbs or wild flowers, without the specially bred flowers we have today. Flowers like the iris, chrysanthemum, lily, and delphinium were known, but not often featured in garden scenes. Formal flowerbeds seem to have had mandrake, poppy, cornflower, and/or lotus and papyrus.

Because Egypt has a very dry climate, caring for gardens meant constant work and depended on irrigation. Skilled gardeners were hired by temples and wealthy families. Their jobs included planting, weeding, watering with a shadoof (a water-lifting tool), pruning fruit trees, digging the ground, and harvesting fruit.

Greek and Roman Gardens

Hellenistic Gardens: Public Beauty

It's interesting that while Egyptians and Romans loved gardening, Greeks didn't usually have private gardens. They did put gardens around temples and decorated walkways with statues. But the fancy, pleasure gardens that showed wealth in other cultures seem to have been missing in Greece.

Roman Gardens: Private Retreats

Roman gardens were places of peace and quiet, a escape from city life. Gaius Maecenas, a friend of Emperor Augustus, built Rome's first private garden estate. He did this to help his creative ideas and improve his health. Seneca the Younger said the gardens' mix of art, nature, and water "calmed his worried mind with the sound of rippling waters."

Growing ornamental plants became very advanced during Roman times. The Roman Empire (around 100 BC–500 AD) actively shared information about farming, gardening, animal care, and plants. Seeds and plants were traded widely. The Gardens of Lucullus (Horti Lucullani) in Rome brought the Persian garden style to Europe around 60 BC.

Chinese and Japanese Gardens: Nature's Art

Both Chinese and Japanese garden design traditionally try to look like natural mountains and rivers. However, how you were meant to view the gardens was different. Chinese gardens were meant to be walked through and enjoyed from inside the garden, as a setting for daily life. Japanese gardens, with a few exceptions, were meant to be viewed from inside the house, almost like a diorama (a 3D scene). Also, Chinese gardens often had water features. Japanese gardens, in a wetter climate, often just hinted at water, using sand or pebbles raked into wave patterns.

Traditional Chinese gardens also treated plants in a more natural way. Traditional Japanese gardens might have plants trimmed into mountain or cloud shapes. This is different from how they used stones. In a Japanese garden, stepping stones were placed in groups as part of the landscape. But in a Chinese garden, a special stone might even be placed on a stand in a noticeable spot so it could be better appreciated.

Chinese Scholar Gardens: Balance and Symbolism

The style of Chinese gardens changed depending on how wealthy people were and which dynasty was in power. For rich people, scholar gardens often had rocks, water, bridges, and pavilions. For most people, courtyards, wells, and clay fish tanks were common. Other features like moon gates and "leaky windows" (open screens in walls) were seen in both types of gardens.

The development of landscape design in China was shaped by the ideas of Confucianism and Taoism. Straight lines and showing social class differences were common in Asian city designs, reflecting Confucian ideas. While British homes used nature outside for privacy, Chinese homes were groups of buildings facing one or more courtyards. The Chinese valued natural spaces inside their homes, where families spent time together. Courtyards in Chinese homes showed Taoist ideas. Families tried to create abstract versions of nature, not exact copies. For example, a Taoist garden would avoid straight lines and use stone and water instead of many trees.

There are two main ways to look at the special design features of the Chinese garden: first, the idea of Yin and Yang; and second, the myths of long life that appeared during the Qin dynasty.

The idea of Yin and Yang shows balance and harmony. The Chinese garden expresses its connection to nature and balance by copying natural settings. This is why it has mountains, rocks, water, and wind elements. Yin and Yang put opposite things together: as hard as rock can be, the softness of water can wear it away. Lake Tai rocks, which are limestone worn down by the water of Lake Tai, are a perfect example. Water, air, and light pass through the rock as it sits still. The "leaky windows" in Chinese garden walls show both stillness and movement. The windows create a solid picture on walls, but that stillness changes when the wind blows or your eyes move.

A Chinese garden's structure is based on the culture's creation story, rooted in rocks and water. To live a long life means to live among mountains and water. It means living with nature, like an immortal being (Xian). The garden suggests a healthy lifestyle that makes one immortal, free from city problems. So, Chinese landscapes are known as Shan (mountain) and Shui (water).

Symbolism is a key part of Chinese garden design. A touch of red or gold is often added to the earthy colors of the Chinese garden. This creates a Yin/Yang contrast. The colors red and gold also stand for luck and wealth. Bats, dragons, and other mythical creatures carved on wooden doors are also common in Chinese gardens. These are seen as signs of luck and protection.

Circles show togetherness, especially for family members. They are seen in moon gates, moon bridges, and round tables placed within square backgrounds. The moon gate and other unique doorways also frame views. They make the viewer pause before moving into a new space.

Paths in Chinese gardens are often uneven and sometimes zig-zag. These paths are like the journey of human life. There is always something new or different when seen from a different angle. The future is unknown and surprising.

European Gardens: From Monasteries to Mansions

Byzantine Gardens: A Blend of Cultures

The Byzantine empire lasted over 1000 years (330–1453 AD) and covered a huge area. Because of this long history and many changes, there isn't one single "Byzantine garden style." We don't have much physical evidence of public, imperial, or private gardens. So, researchers have used old writings to find clues about Byzantine gardens. Romance novels from the 1100s, like Hysmine and Hysminias, had detailed garden descriptions. Their popularity shows that Byzantines loved pleasure gardens. More formal gardening books, like the Geoponika (900s), were like encyclopedias of farming practices. These books were published and translated many times, showing how much people valued ancient gardening knowledge. They acted as guides, promoting the idea of walled gardens with plants arranged by type. These ideas were seen in the suburban parks and palace gardens of Constantinople.

The Byzantine garden tradition was shaped by big historical changes. First, Constantine the Great made Christianity the empire's official religion. This meant moving away from the decorative pagan statues of Greco-Roman gardens. Second, there was more contact with Islamic nations in the Middle East after the 800s. Fancy decorations in the emperor's palace and the use of moving figures in palace gardens show this influence. Third, Byzantine cities changed after the 600s. They became smaller and more rural. The number of rich people who could afford grand gardens likely shrank too. Finally, there was a shift towards a more "enclosed" garden space (hortus conclusus). This was a popular trend in Europe at the time. The open views of Roman villas were replaced by garden walls with scenic views painted on the inside. The idea of heaven as an enclosed garden became popular, especially after the 600s, when there was more focus on divine punishment and repentance.

One area of gardening that thrived in Byzantium was practiced by monasteries. While there isn't much archaeological proof, we can learn a lot from the founding documents of Christian monasteries and stories about saints who gardened. These sources tell us that monasteries had monastic gardens outside their walls. They watered them with complex irrigation systems from springs or rainwater. These gardens had vineyards, vegetables, and fruit trees to feed monks and visitors. Monks often took on the role of gardener as a humble act. Monastic gardening practices from that time are still used in Christian monasteries in Greece and the Middle East today.

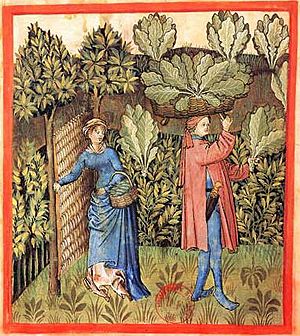

Medieval Gardens: Monasteries and Utility

Monasteries kept gardening traditions alive during the medieval period in Europe. They used many different gardening techniques for various purposes, showing how advanced they were. We have limited records of their practices, and no monastic gardens exist today exactly as they were. However, records and plans, like those for St. Gall in Switzerland, show the types of gardens a monastery might have had.

Generally, monastic gardens included kitchen gardens, infirmary (sick-room) gardens, cemetery orchards, cloister garths, and vineyards. Some monasteries also had a "green court," a grassy area with trees where horses could graze. There were also private gardens for monks who held specific jobs.

For practical reasons, vegetable and herb gardens provided food and medicinal plants. These could feed or treat the monks and sometimes the local community. As shown in the St. Gall plans, these gardens were laid out in rectangular plots with narrow paths. This made it easy to collect crops. These beds were often surrounded by wattle fencing to keep animals out. Kitchen gardens might grow fennel, cabbage, onions, garlic, radishes, and parsnips. Infirmary gardens could have plants like roses, savory, rosemary, mint, and cumin.

The herb and vegetable gardens had another purpose beyond just producing food. Their creation and care allowed the monks to fulfill the manual labor part of their religious life, as required by the Rule of St. Benedict.

Orchards also produced food and provided opportunities for manual labor. Cemetery orchards, like the one in the St. Gall plan, had even more uses. The cemetery orchard not only grew fruit but also symbolized the garden of Paradise. This idea of a garden meeting both physical and spiritual needs was also seen in the cloister garth.

The cloister garth was a rectangular grassy area surrounded by arched walkways. It was closed to outsiders and mainly served as a quiet place for meditation. The garth was often divided into quarters by paths. It usually had a covered fountain in the center or on the side. This fountain provided water for washing and irrigation, meeting more practical needs. Some cloister gardens also had small fish ponds, another food source. The walkways were used for teaching, sitting, meditating, or exercising in bad weather.

Many people wonder how the garth helped with spiritual life. Umberto Eco said the green grass was like a soothing sight for tired eyes, helping monks return to reading with new energy. Some scholars suggest that even though it had few plants, the cloister garth might have inspired religious visions. This idea of giving gardens symbolic meaning wasn't just for religious groups; it was common in medieval culture. The square cloister garth was meant to represent the four directions, and thus the entire universe. As Turner explains, "Augustine inspired medieval garden makers to ignore earthly things and look up for divine inspiration. A perfect square with a round pool and a five-sided fountain became a tiny universe, showing the mathematical order and divine grace of the larger universe."

Walking around the cloister while meditating was a way to follow the "path of life." Indeed, each monastic garden had both symbolic and practical value, showing the cleverness of its creators.

In the later Middle Ages, books, art, and stories show how garden design developed. From the late 1100s to the 1400s, European cities were walled for defense and to control trade. Even though space inside these walls was limited, old documents show that animals, fruit trees, and kitchen gardens existed within city limits.

Pietro Crescenzi, a lawyer from Bologna, wrote 12 books in the 1200s about practical farming. His text describes medieval gardening practices. From his book, we know that gardens were surrounded by stone walls, thick hedges, or fences. They also included trellises and arbors. They took their shape from the square or rectangular cloister and had square planting beds.

Grass was also first noted in medieval gardens. In De Vegetabilibus by Albertus Magnus, written around 1260, there are instructions for planting grass plots. Raised banks covered in turf, called "turf seats," were built for sitting in the garden. Fruit trees were common and often grafted to create new types of fruit. Gardens included a raised mound or "mount" to serve as a viewing platform. Planting beds were usually raised on platforms.

Two works from the late Middle Ages discuss plant growing. In the English poem "The Feate of Gardinage" by Jon Gardener and the household advice in Le Ménagier de Paris from 1393, many herbs, flowers, fruit trees, and bushes were listed with growing instructions. The Ménagier gives advice by season on sowing, planting, and grafting. The most advanced gardening during the Middle Ages was done at monasteries. Monks developed gardening techniques and grew herbs, fruits, and vegetables. Using their medicinal herbs, monks treated those who were sick inside the monastery and in nearby communities.

During the Middle Ages, gardens were thought to connect the earthly with the divine. The enclosed garden as a symbol for paradise or a "lost Eden" was called the hortus conclusus. Full of religious meaning, enclosed gardens were often shown in art. They pictured the Virgin Mary, a fountain, a unicorn, and roses inside an enclosed area.

Even though Medieval gardens lacked many features of the Renaissance gardens that came after them, some of their characteristics are still used today.

The Renaissance: A New Era for Gardens

The Italian Renaissance started a big change in private gardening. Renaissance private gardens were filled with scenes from old myths and other learned ideas. Water during this time was especially symbolic. It was linked to fertility and nature's abundance.

The first public parks were built by the Spanish Crown in the 1500s, both in Europe and the Americas.

French Baroque: Grand and Formal Gardens

The Garden à la française, or Baroque French gardens, followed the style of André Le Nôtre.

The French Classical garden style reached its peak during the rule of Louis XIV of France (1638–1715) and his head gardener of Gardens of Versailles, André Le Nôtre (1613–1700). These gardens were inspired by the Italian Renaissance gardens of the 1300s and 1400s, and ideas from French philosopher René Descartes (1576–1650). At this time, the French made gardens much larger than their Italian predecessors. Their gardens showed how the king and "man" controlled and shaped nature to display their power, wealth, and authority.

Renée Descartes, who created analytical geometry, believed that the natural world could be measured. He thought that space could be divided endlessly. His idea that "all movement is a straight line, therefore space is a universal grid of mathematical coordinates" gave us Cartesian mathematics. Through the classical French gardens, this idea was shown physically and visually.

This formal French garden style placed the house in the center of a huge, mostly flat piece of land. A large central path, which got narrower further from the house, made the viewer's eye go to the horizon. This made the property look even bigger. The viewer was meant to see the property as one whole, but couldn't see all parts of the garden at once. You were led through a logical story and surprised by things that weren't visible until you got closer. There was a symbolic story about the owner told through statues and water features with mythological references. Small, almost unnoticeable changes in ground level helped hide the garden's surprises and made the views seem longer.

These grand gardens had organized spaces meant to be elaborate stages for entertaining the court and guests with plays, concerts, and fireworks. The following garden features were used:

- allée (a path lined with trees)

- axis of symmetry (a central line where both sides are balanced)

- bosquet (a formal grove of trees)

- broderie (fancy, embroidered-like patterns in plants)

- canal (a long, narrow waterway)

- cul de sac (a dead-end path)

- fountains

- gloriette (a small, open building)

- grottos with rocaille (cave-like structures with shell decorations)

- jeux d'eau (water games or displays)

- orangerie (a building for growing citrus trees)

- parterre (a formal garden with paths and beds in patterns)

- patte d'oie (a "goose foot" pattern of three paths spreading out)

- sylvan theater (an outdoor theater in a wooded area)

- tapis vert (a "green carpet" of lawn)

- topiary (plants shaped into designs)

Mediterranean Gardens: Fruitfulness and Frugality

Mediterranean soil was delicate because it was used for centuries. So, the region's landscape culture was a mix of growing lots of food and being careful with resources. The area mostly had small farms. After World War II, Mediterranean immigrants brought this farming style to Canada. There, fruit trees and vegetables in backyards became common.

English Landscape Gardens: Natural Beauty

Forests played several roles for the British in the Middle Ages. One role was to provide game for the wealthy. Lords with valuable land were expected to have many animals for hunting when royals visited. Even though they were natural, forested manor homes could show status, wealth, and power if they had all the comforts. After the Industrial Revolution, Britain's forest industry shrank. In response, the Garden City Movement brought city planning to industrial areas in the early 1900s. This was to balance negative industrial effects like pollution.

Several traditions influenced English gardening in the 1700s. One was planting woods around homes. By the mid-1600s, coppice planting (cutting trees to grow new shoots) became common and looked good. While forests were more useful for hunting in medieval Britain, 1700s gardening moved from practical use to pleasing the senses.

English pleasure grounds were also influenced by Medieval groves. Some of these still existed in 1700s Britain. This influence appeared as shrubbery, sometimes arranged in mazes. And though ancient, shredding (a tree-pruning method) became common in these early gardens. This method allowed light to enter the understory (plants under taller trees). Shredding was used to create garden groves. These ideally included an orchard with fruit trees, fragrant herbs and flowers, and mossy paths.

The first known botanical garden was in Pisa in 1543. The first English botanical garden was found in Oxford in 1621. Near London, the gardens at Kew were started in 1759. Augusta, dowager princess of Wales worked with famous botanists like Lord Bute and Stephen Hales. They greatly expanded the garden with exotic plants. By 1769, Kew Gardens had over 3,400 types of plants.

The picturesque garden style appeared in England in the 1700s. It was part of the larger Romantic movement. Garden designers like William Kent and Capability Brown copied the symbolic landscape paintings of European artists. These included Claude Lorraine, Poussin, and Salvator Rosa. The shaped hills, lakes, and trees with symbolic temples were sculpted into the land.

By the 1790s, people started to react against these typical designs. Some thinkers began to promote the idea of picturesque gardens. The leader was landscape theorist William Gilpin, a skilled artist known for his realistic nature paintings. He preferred natural landscapes over manicured ones. He urged designers to work with the land's natural shape. He also noted that while classical beauty was smooth and neat, picturesque beauty was wilder and untamed. The picturesque style also included architectural follies. These were fake castles, Gothic ruins, or rustic cottages built to add interest to the landscape.

Arguments between the picturesque style and supporters of more manicured gardens continued into the 1800s. Landscape designer Humphry Repton supported Gilpin's ideas, especially that the garden should fit with the surrounding land. He was criticized by two rival theorists, Richard Payne Knight and Uvedale Price. Repton responded by pointing out the differences between painting and landscape gardening. William Shenstone is credited with coining the term ‘landscape gardening’. Unlike a painting, a viewer moves through a garden, constantly changing their view.

The French landscape garden, also called the jardin anglais or jardin pittoresque, was influenced by English gardens of the time. Rococo features like Turkish tents and Chinese bridges were common in French gardens in the 1700s. The French Picturesque garden style falls into two groups. One group was staged, almost like theater sets, usually rustic and exotic. This was called jardin anglo-chinois. The other group was filled with romantic, simple country feelings, influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The first style is seen in the Désert de Retz and Parc Monceau. The second is seen in the Moulin Jolie.

The rustic look in French picturesque gardens also came from admiring Dutch 1600s landscape paintings. It also came from the works of French 1700s artists like Claude-Henri Watelet, François Boucher, and Hubert Robert.

"English garden" is the common term in English-speaking countries for gardens that copy or are inspired by the original Landscape Garden examples.

Gardenesque Gardens: Showing Off Plants

The gardenesque style of English garden design grew in the 1820s. It came from Humphry Repton's Picturesque or "Mixed" style. It was largely developed by J. C. Loudon, who created the term.

In a gardenesque plan, all trees, shrubs, and other plants are placed and cared for so that each plant's unique character can be fully seen. As botany became a popular subject, the gardenesque style focused on interesting plants and a collector's approach. New plants that would have seemed strange before found a place. Examples include pampas grass from Argentina and monkey-puzzle trees from Chile. Winding paths connected scattered plantings. The gardenesque approach created small landscapes with many features and scenes. This promoted beauty in detail, variety, and mystery, sometimes making the overall design less clear. Artificial mounds helped arrange groups of shrubs, and island beds (beds surrounded by lawn) became important features.

Wild Gardens and Herbaceous Borders: Natural and Colorful

The books by William Robinson describing his "wild" gardening at Gravetye Manor in Sussex were influential. So was the sweet, idealized picture of a "cottage garden" shown by Kate Greenaway, which hadn't really existed historically. Both influenced the development of the mixed herbaceous borders. These were promoted by Gertrude Jekyll at Munstead Wood in Surrey from the 1890s. Her plantings mixed shrubs with perennial (returning each year) and annual (lasting one year) plants and bulbs. These were in deep beds within more formal terraces and stairs designed by Edwin Lutyens. This set the standard for high-style, high-maintenance gardening until World War II. Vita Sackville-West's garden at Sissinghurst Castle, Kent, is the most famous and influential garden of this romantic style. It was made popular by her gardening column in The Observer. The trend continued with Margery Fish's gardening at East Lambrook Manor. In the last 25 years of the 1900s, less structured wildlife gardening became popular. It focused on the ecological side of similar gardens using native plants. A leading supporter in the United States was landscape architect Jens Jensen. He designed city and regional parks, and private estates, with a refined sense of art and nature.

Mesoamerican Gardens: Ancient American Traditions

In the Western Hemisphere, various Mesoamerican cultures had gardening traditions for both practical use and beauty. These included the Maya, Mixtecs, and Nahua peoples (like the Aztec Empire). The Maya used forest gardens extensively to grow food and medicinal plants, even within their cities.

The Aztec elite built elaborate pleasure gardens in the Valley of Mexico. These had different types of plants and water features like fountains fed by aqueducts. Aztec and Maya gardens focused strongly on fertility because they were mainly for farming. The Aztecs also loved flowers, giving them great religious, symbolic, and philosophical meaning.

Contemporary Gardens: Modern and Sustainable

In the 1900s, modern garden design became important. Architects started designing buildings and homes with new, simple ideas. They moved away from the formal Beaux-Arts style, removing unnecessary decorations. Garden design naturally followed this idea of "form following function," considering how plants would grow. After World War II, people in the United States, especially in western states, spent more time outdoors. Magazines like Sunset promoted this, and the backyard often became an outdoor room.

Frank Lloyd Wright showed his idea of the modern garden by designing homes that fit perfectly with nature. Taliesin and Fallingwater are examples of how architecture can blend seamlessly with its surroundings. His son, Lloyd Wright, trained in architecture and landscape architecture. He practiced an innovative way of combining buildings and landscapes in his work.

Later, Garrett Eckbo, James Rose, and Dan Kiley, known as the "bad boys of Harvard," became important pioneers in modern garden design. They met while studying traditional landscape architecture. As Harvard embraced modern design in its architecture school, these designers wanted to bring those new ideas into landscape design. They became interested in creating useful outdoor spaces that echoed natural surroundings. Modern gardens feature a fresh mix of curved and architectural designs. Many include abstract art in geometric shapes and sculptures. Spaces are defined by carefully placed trees and plants. The work of Thomas Church in California was influential through his books. In Sonoma County, California, his 1948 Donnell garden's swimming pool, which was kidney-shaped with an abstract sculpture, became a symbol of modern outdoor living.

In Mexico, Luis Barragán combined International style modernism with traditional Mexican elements. He did this in private estates and housing projects like Jardines del Pedregal and the San Cristobal 'Los Clubes' Estates in Mexico City. In public design, the Torres de Satélite are large urban sculptures in Naucalpan, Mexico. His house, studio, and gardens, built in 1948 in Mexico City, became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004.

Roberto Burle Marx is credited with bringing modernist landscape architecture to Brazil. He was known as a modern nature artist and a public urban space designer. He was a landscape architect (and also a botanist, painter, print maker, ecologist, naturalist, artist, and musician). He designed parks and gardens in Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and in the United States in Florida. He worked with architects Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer on the landscape design for some of the important modernist government buildings in Brazil's capital, Brasília.

Famous Gardeners in History

The following people, listed roughly in historical order, made important contributions to the history of gardens. They were botanists, explorers, designers, garden-makers, or writers. You can find more information about them in their individual articles.

- Theophrastus

- Lucullus

- Tiberius

- Pliny the Elder

- Pliny the Younger

- Pacello da Mercogliano

- John Tradescant the elder and his son

- Carolus Clusius

- André le Nôtre

- Thomas Hill

- John Evelyn

- George London

- Henry Wise

- William Kent

- Lancelot "Capability" Brown

- Humphry Repton

- Andrew Jackson Downing

- Frederick Law Olmsted

- George Loddiges

- Giovanni Baptista Ferrari

- John Loudon

- Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell

- Peter Joseph Lenné

- Joseph Paxton

- Thomas Jefferson

- William Robinson (gardener)

- Gertrude Jekyll

- Constance Villiers-Stuart

- Lawrence Johnston

- Edwin Lutyens

- Vita Sackville-West

- Claude Monet

- Jens Jensen

- Theodore Payne

- Beatrix Farrand

- Florence Yoch + Louise Council

- Ganna Walska

- Lockwood DeForest

- A.E. Hanson

- Russell Page

- Luis Barragán

- Gustav Ammann

- Lawrence Halprin

- Roberto Burle Marx

- Xavier de Winthuysen

- Nicolau María Rubió i Tudurí

- Sylvia Crowe

- Pietro Porcinai

- Gerard Ciołek

- Gilles Clément

Famous Historic Gardens Around the World

Brazil

- Brasília - selected locations; (Roberto Burle Marx)

- Ibirapuera Park, São Paulo

Canada

- The Butchart Gardens (British Columbia) (1909)

- Halifax Public Gardens (Nova Scotia) (1867)

- Royal Botanical Gardens (Ontario) (1932)

- Montreal Botanical Garden (Quebec) (1931)

China

- Gardens of Suzhou

- Summer Palace

- Beihai Park

- Yuyuan Garden

- Prince Gong Mansion

England

Public Gardens in England

- Meadow of Moorfields, London (1605) (destroyed)

- Hyde Park, London (1728)

- Peel Park, Salford (1846)

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond (1771)

Private Gardens in England

- Blenheim Palace

- Chatsworth

- Fountains Abbey

- Hidcote Manor Garden

- Lost Gardens of Heligan

- Rousham House

- Sissinghurst Castle

- Stourhead

- Stowe Gardens

France

Public Gardens in France

- Champs-Élysées, Paris (1640)

- Jardin des Tuileries, Paris (1664)

- Bois de Boulogne, Paris (1852)

- Place des Vosges, Paris (1682)

Private Gardens in France

- Chateau Fontainebleau

- Château de Marly

- Château de Villandry

- Parc Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Fondation Monet in Giverny

- Gardens of Versailles

- Potager du roi, Versailles (King's Kitchen Garden)

- Vaux-le-Vicomte

Germany

- Muskau Park

- Dessau-Wörlitz Garden Realm

- Herrenhausen Gardens

Hungary

- City Park (Budapest) (1810)

India

- Shalimar Gardens (Jammu and Kashmir)

- Brindavan Gardens (Mysore)

- Amrit Udyan at Rashtrapati Bhavan, (Delhi)

Iraq

Ireland

- Historic Cork Gardens

- Powerscourt Gardens

- Mount Usher Gardens

Israel

- Bahá'í Hanging Gardens of Haifa

Italy

Public Gardens in Italy

- Poplars mall in Campo Vaccino in the area of the ancient Roman Forum, Rome (1656) (destroyed)

Private Gardens in Italy

- Bomarzo

- Hadrian's Villa

- Villa d'Este

- Giardino Giusti

- Reggia di Caserta

- Boboli Gardens

- Villa Gamberaia

- Villa Lante

- Villa Massei

Japan

- Daisen-in

- Ryōan-ji

- Katsura Imperial Villa

- Shugakuin Imperial Villa

Malaysia

- KLCC Park, Kuala Lumpur

Mexico

- Alameda Central, Mexico City (1592)

- Jardín Borda, Cuernavaca (1783)

Netherlands

- Elswout near Haarlem

- Het Loo

- The gardens of Twickel Castle, Weldam Castle and Warmelo Castle in Hof van Twente

- The Gardens of Mien Ruys in Dedemsvaart

- The Garden of Piet Oudolf in Hummelo

Norway

- Frogner Park

- Palace Park

- Nygårdsparken

Pakistan

- Shalimar Gardens (Lahore)

Peru

- Alameda de los Descalzos, Lima (1611)

Poland

- Arkadia

- Baranów Sandomierski

- Krasiczyn

- Łazienki Park, Warsaw

- Muskauer Park

- Nieborów

- Saxon Garden, Warsaw

- Wilanów

Russia

- Kuskovo

- Arkhangelskoye Estate

- Tsaritsyno

- Oranienbaum

- Ostafyevo

- Vlakhernskoye-Kuzminki

- Pavlovsk

- Peterhof Palace

- Summer Garden

- Monrepo

- Lyublino

Scotland

Public Gardens in Scotland

- Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh (1670)

Spain

Public Gardens in Spain

- La Alameda de Hércules, Seville (1574)

- Paseo de San Pablo de Écija (Sevilla) (1578) (destroyed)

- Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid (1781)

Private Gardens in Spain

- Alhambra. A Royal park that was closed to the public.

- Real Alcázar de Sevilla. A Royal park that was closed to the public.

- Monforte

- Laberinto de Horta

- El Capricho de la Alameda de Osuna

- La Concepción

- El Retiro. A Royal park that was closed to the public.

- Fábrica de Paños de Brihuega

- Pazo de Oca

Sweden

Public Gardens in Sweden

- Bergianska trädgården

- Botaniska trädgården (Lund)

- Botaniska trädgården (Uppsala)

- Drottningholm Palace

- Gothenburg Botanical Garden

- Hagaparken

- Linnaean Garden

- Linnaeus Hammarby

- Norrviken Gardens

- Sofiero Palace

Ukraine

- A.V. Fomin Botanical Garden

- Kremenets Botanical Garden

- Sofiyivsky Park

- M.M. Gryshko National Botanical Garden

United States

Public Gardens in the United States

- Central Park, New York City

- Boston Common, Boston, (1830)

- Golden Gate Park, San Francisco (1860)

Private Gardens in the United States

- Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

- Huntington Gardens, San Marino

- Lotusland, Montecito

- Casa del Herrero, Montecito

- Filoli, Woodside

- Ruth Bancroft Garden, Walnut Creek

- Allerton Garden, Kauai, Hawaii

- Longwood Gardens, Kennett Square, Pennsylvania

- Nemours Mansion and Gardens, Wilmington, Delaware

- Winterthur Museum and Country Estate, Winterthur, Delaware

- Fair Lane, Dearborn, Michigan

- Gaukler Point, Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan

- Meadowburn Farm (Helena Rutherfurd Ely), Vernon Township, New Jersey.

Venezuela

- Parque del Este, Caracas

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la jardinería para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la jardinería para niños

- Index of gardening articles (main resource)

- Landscape design history

- Gardens by country

- List of garden types

- Landscape Institute

- Museum of Garden History

- Australian Garden History Society

- The Garden Conservancy

- Garden tourism

- Historic garden conservation