Vita Sackville-West facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vita Sackville-West

|

|

|---|---|

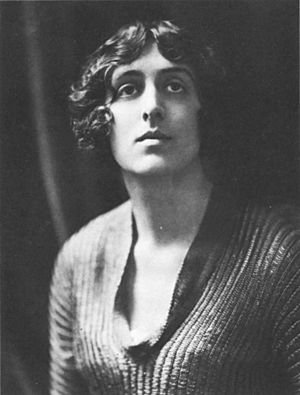

Sackville-West around 1915, from The Life of V.Sackville-West by Victoria Glendinning

|

|

| Born | Victoria Mary Sackville-West 9 March 1892 Knole House, Kent, England |

| Died | 2 June 1962 (aged 70) Sissinghurst Castle, Kent, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, garden designer |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1917–1960 |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

Victoria Mary, Lady Nicolson, known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and garden designer. She was born on March 9, 1892, and passed away on June 2, 1962.

Vita Sackville-West was a very successful writer. She wrote novels, poems, and worked as a journalist. She also wrote many letters and kept a diary. She published over a dozen poetry books and 13 novels.

She won the Hawthornden Prize twice for her writing. In 1927, she won for her long poem The Land. She won again in 1933 for her Collected Poems. Her friend, the famous writer Virginia Woolf, based a character on Vita in her novel Orlando: A Biography.

From 1946 to 1961, Vita wrote a column for The Observer newspaper. She is also famous for the beautiful garden at Sissinghurst in Kent. She created this garden with her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson.

Contents

About Vita Sackville-West

Her Family and Childhood Home

Victoria Mary Sackville-West was born on March 9, 1892. Everyone called her Vita to tell her apart from her mother, who was also named Victoria. She was born at Knole, a large family home in Kent, England. Knole had been in her family for a very long time.

Vita was the only child of her parents, Victoria Sackville-West and Lionel Sackville-West, 3rd Baron Sackville. Her mother grew up in a convent in Paris.

Vita's parents were happy at first, but they grew apart after she was born. Knole was a very old and important family home. However, because of old English inheritance customs, Vita could not inherit Knole when her father died. This made her sad throughout her life. The house went to her father's brother instead.

Vita's Early Years and Education

Vita was taught at home by teachers called governesses. Later, she went to an exclusive school for girls in London. There, she met her first loves, Violet Keppel and Rosamund Grosvenor. She found it hard to make friends with other children. People who wrote about her life said she felt lonely and isolated as a child.

She wrote a lot at Knole. Between 1906 and 1910, she wrote eight full-length novels, though they were never published. She also wrote poems and plays, some in French. Because she didn't have a formal education, she sometimes felt shy around other smart people, like those in the Bloomsbury Group. She felt she wasn't as quick-minded as them.

Vita had a strong interest in "gypsy" ways, which she saw as passionate and romantic. This theme appeared often in her writing. She visited Roma camps and felt a connection to their culture. Vita also spent a lot of time in Paris when she was young.

Marriage to Harold Nicolson

Vita Sackville-West was courted by a young diplomat named Harold Nicolson for 18 months. Vita's parents did not want them to marry. They thought Harold did not earn enough money. He worked at the British Embassy in Constantinople (now Istanbul).

Harold Nicolson became a diplomat, journalist, politician, and writer. After they married in 1913, Vita and Harold lived in Constantinople. Vita loved the city, but she did not enjoy the duties of a diplomat's wife. She later wrote that she tried to be a "correct and adoring wife."

In 1914, Vita became pregnant, so they returned to England. They wanted her to give birth in a British hospital. The family lived in London and bought a country house called Long Barn in Kent. They hired an architect named Edwin Lutyens to improve the house. They could not return to Constantinople because Britain declared war on the Ottoman Empire.

Vita and Harold had two sons. Benedict Nicolson (1914–1978) became an art historian. Nigel Nicolson (1917–2004) became a well-known editor, politician, and writer. Another son was stillborn in 1915.

Sissinghurst Castle Garden

In 1930, Vita's family bought Sissinghurst Castle in Kent and moved there. This castle had once belonged to Vita's ancestors. This was special to her because she could not inherit her childhood home, Knole. Sissinghurst was an old ruin, and creating the gardens became a huge project for Vita and Harold. It took many years to clear the land.

Harold designed the strong, classical structure of the garden. Vita then filled it with her creative and informal planting ideas. She made different "rooms" in the garden, like the White Garden, Rose Garden, and Orchard. She also created gardens with single color themes. Her goal was for visitors to explore and discover new things. She had practiced her ideas at her first garden at Long Barn. Sissinghurst was first opened to the public in 1938.

Vita started writing again in 1930 after a six-year break. She needed money to pay for Sissinghurst. Harold had left his job as a diplomat, so he no longer had that salary. They also needed money for their sons' school tuition at Eton College. Vita felt her writing improved with help from Virginia Woolf.

In 1947, she began a popular weekly column in The Observer called "In your Garden." She was not a trained gardener, but her column was very popular. She continued writing it until a year before she died. Her writing helped make Sissinghurst one of England's most famous gardens. In 1948, she helped start the garden committee for the National Trust. Today, the National Trust manages Sissinghurst. Vita received the Veitch Memorial Medal from the Royal Horticultural Society.

Vita's Writing Career

In the early 1920s, Vita wrote a memoir called Portrait of a Marriage. It was published in 1973, after her death. The BBC made it into a TV series in 1990, which won several awards.

Most of Vita's novels were very popular when they were published. The Edwardians (1930) and All Passion Spent are two of her most famous novels today. All Passion Spent was also made into a BBC TV show in 1986.

A story she wrote in 1922, "A Note of Explanation," was recently found. It was written for the miniature library in Queen Mary's Dolls' House. The story is about a tiny sprite who lives in the doll's house and retells fairy tales. This book was turned into a play in 2019.

Vita's poetry is less known. She wrote long poems and translated works by other poets, like Rainer Maria Rilke's Duino Elegies. Her long poems The Land (1926) and The Garden (1946) show her love for nature and family traditions. The Land won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927. She won this prize again in 1933 for her Collected Poems, making her the only writer to win it twice. The Garden won the Heinemann Award.

She also wrote biographies, which are books about other people's lives. Her most famous biography is about Saint Joan of Arc. She also wrote about Saint Teresa of Ávila and Thérèse of Lisieux, the author Aphra Behn, and her grandmother, the dancer Pepita.

Even though she was shy, Vita often gave readings of her work. She did this for book clubs and on the BBC. She wanted to feel like she belonged. By the 1940s, some critics thought her writing style was old-fashioned. In 1947, Vita Sackville-West became a member of the Royal Society of Literature and a Companion of Honour.

Later Life and Legacy

Vita Sackville-West passed away at Sissinghurst in June 1962. She was 70 years old and died from cancer. Her ashes were buried in her family's crypt at a church in Withyham.

Sissinghurst Castle is now owned by the National Trust. Her son, Nigel Nicolson, lived there after her death. After Nigel passed away in 2004, his son Adam Nicolson moved in with his family. Adam and his wife, Sarah Raven, are working to bring back the farm at Sissinghurst. They want to grow food there for people who live and visit.

A film called Vita and Virginia was released in 2018. It stars Gemma Arterton as Vita and Elizabeth Debicki as Virginia Woolf. The movie is based on a play that used letters written between Vita and Virginia.

Works by Vita Sackville-West

Fiction

Poetry

Vita Sackville-West's poems often explored nature and romantic love. She published over a dozen poetry collections, including:

- Timgad: [a poem] (1900)

- Constantinople: eight poems (1915)

- Poems of West & East (1917)

- The Land (1926)

- King's daughter (1929)

- Invitation to cast out care (1931)

- Sissinghurst (1931)

- Collected poems (1933)

- Solitude: a poem (1938)

- The Garden (1946)

- Lost poem (or A Madder Caress) (2013)

Novels

- Heritage (1919)

- The dragon in shallow waters (1920)

- Challenge (1920)

- Grey Wethers: a romantic novel (1923)

- The Edwardians (1930)

- All Passion Spent (1931)

- Family History (1932)

- The Dark Island (1934)

- Grand Canyon: A Novel (1942)

- Devil at Westease: the story as related by Roger Liddiard (1947)

- The Easter party (1953)

- No Signposts in the Sea (1961)

Children's Books

- A Note of Explanation (written for Queen Mary's Dolls' House in 1924, published in 2017)

Short Stories

- Orchard and vineyard (1892)

- The heir: a love story (1922)

- Thirty Clocks Strike the Hour, and other stories (1932)

- The death of Noble Godavary (Gottfried Künstler, 1932)

- Another world than this ..: an anthology (1945)

- Nursery rhymes (1947)

Plays

- Chatterton: a drama in three acts (1909)

Non-fiction

Letters

- Dearest Andrew: letters from V. Sackville-West to Andrew Reiber, 1951-1962 (1979)

- The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf (1984)

- Vita and Harold: The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson (1992)

- Violet to Vita: The Letters of Violet Trefusis to Vita Sackville-West 1910–1921 (1991)

- Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson by Nigel Nicolson (1973)

- Love Letters: Vita and Virginia by Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West (2021)

Biographies

- Aphra Behn, the incomparable Astrea (1927)

- Andrew Marvell (1929)

- Saint Joan of Arc (1936)

- Pepita (1937)

- The eagle and the dove, a Study in Contrasts: St. Teresa of Avila and St. Thérèse of Lisieux (1943)

- Daughter of France: the life of Anne Marie Louise d'Orléans, duchesse de Montpensier, 1627-1693, La Grande Mademoiselle (1959)

Guides and Other Non-fiction

- Knole and the Sackvilles (1922) - a history of her family home

- Passenger to Teheran (1926)

- Twelve Days: an account of a journey across the Bakhtiari Mountains of South-western Persia (1927)

- How does your garden grow? (1935)

- Some flowers (1937)

- Country notes (1939)

- Country Notes in Wartime (1940)

- English country houses (1941)

- The Women's Land Army (1944)

- Exhibition Catalogue: Elizabethan portraits (1947)

- Knole, Kent (1948)

- In Your Garden (1951)

- In your garden again (1953)

- Walter de la Mare and The traveller (1953)

- More for your garden (1955)

- Even more for your garden (1958)

- Joy of Gardening: a selection for Americans (1958)

- Berkeley Castle (1960)

- Faces: profiles of dogs (1961)

- Garden Book (1975)

- Hidcote Manor Garden, Gloucestershire (1976)

- Une Anglaise en Orient (1993)

Translations

- Duineser Elegien: Elegies from the Castle of Duino, translated from the German of Rainer Maria Rilke by V. and Edward Sackville-West (1931)

In 1931, Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press published a special edition of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies. This was the first time Rilke's famous work was available in English.

Influences and Biographies

- Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf (1928)

- Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West by Matthew Dennison (2014)

See also

In Spanish: Vita Sackville-West para niños

In Spanish: Vita Sackville-West para niños

- List of Bloomsbury Group people

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |