Harold Nicolson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Harold Nicolson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of Parliament for Leicester West |

|

| In office 14 November 1935 – 15 June 1945 |

|

| Preceded by | Ernest Harold Pickering |

| Succeeded by | Barnett Janner |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Harold George Nicolson

21 November 1886 Tehran, Persian Empire |

| Died | 1 May 1968 (aged 81) Sissinghurst Castle, Kent, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | New Party (1931-32) National Labour (1935-45) Labour (from 1947) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Benedict Nicolson Nigel Nicolson |

| Parents | Arthur Nicolson, 1st Baron Carnock Mary Hamilton |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Occupation |

|

Sir Harold George Nicolson (born November 21, 1886 – died May 1, 1968) was a very busy and talented British person. He worked as a politician, a diplomat (someone who represents their country in other nations), a historian, a writer, and even a gardener! His wife, Vita Sackville-West, was also a famous writer.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Harold Nicolson was born in Tehran, Persia (now Iran), on November 21, 1886. He was the youngest son of a diplomat, Arthur Nicolson, 1st Baron Carnock. Because of his father's job, Harold lived in many different places. He grew up traveling across Europe and the Near East. Some of the cities he lived in included St. Petersburg, Constantinople, Madrid, Sofia, and Tangier.

He went to school at The Grange School and then Wellington College. Later, he studied at Balliol College, Oxford, and finished his degree in 1909. That same year, Harold joined the Foreign Office, which is the part of the government that deals with other countries.

Diplomatic Career

In 1909, Harold Nicolson began his career in the British Diplomatic Service. He worked as an attaché in Madrid in 1911. From 1912 to 1914, he served as a Third Secretary in Constantinople (now Istanbul). In 1913, Harold married the well-known novelist Vita Sackville-West.

During the First World War, Harold worked at the Foreign Office in London. He was promoted to Second Secretary. On August 4, 1914, it was his job to deliver Britain's declaration of war to the German ambassador in London. After the war, he helped at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. For his work, he was honored with the title of Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG).

In 1925, he was sent to Tehran as a senior diplomat. That year, General Reza Khan became the new Shah (king) of Persia. Harold Nicolson did not like Reza Khan. He described him as a "bullet-headed man with the voice of an asthmatic child."

Reza Khan wanted to reduce British influence in Iran. He demanded that British guards, called Savars, be removed from Persia. These guards protected British buildings. Harold Nicolson, as the head of the British Legation, strongly objected. He felt the demand was almost insulting. However, the British eventually agreed to remove the Savars.

In 1927, Harold was called back to London. He had criticized his boss, Sir Percy Loraine, in a report. He was sent to Berlin in 1928, but he resigned from the Diplomatic Service in 1929.

Political Career

After leaving diplomacy, Harold Nicolson worked as an editor for the Evening Standard newspaper from 1930 to 1931. He didn't enjoy writing about high-society gossip, so he left after a year.

In 1931, he joined the New Party, led by Sir Oswald Mosley. He tried to become a Member of Parliament (MP) but was not successful. He also edited the party's newspaper. However, when Mosley formed the British Union of Fascists, Harold stopped supporting him.

Harold Nicolson became a Member of Parliament (MP) for Leicester West in 1935. He was part of the National Labour group. In the late 1930s, he was one of the few MPs who warned Britain about the danger of fascism in Europe. He supported Winston Churchill's efforts to prepare Britain for war.

Harold was a big fan of France. He was a close friend of Charles Corbin, the French ambassador to Britain. Corbin also disliked the policy of appeasement, which tried to avoid war by giving in to aggressive demands.

In October 1938, Harold spoke out against the Munich Agreement in Parliament. This agreement allowed Germany to take part of Czechoslovakia. He believed Britain should uphold moral standards in Europe. He said, "I thank God that I possess a Foreign Office mind." This meant he thought like a diplomat who understood international dangers.

During the Second World War, Harold became a Parliamentary Secretary in Churchill's government in 1940. He worked at the Ministry of Information. He was also on the Board of Governors of the BBC from 1941 to 1946.

In 1944, during the Battle of Monte Cassino in Italy, there was a debate about bombing an ancient abbey. Many believed German soldiers were using it to watch Allied forces. Harold Nicolson argued against bombing the abbey. He said that great works of art are irreplaceable. He believed it was better to lose soldiers' lives than to destroy such a historic place. His own son, Nigel Nicolson, was fighting in that battle. Despite his strong feelings, the abbey was bombed on February 15, 1944.

After losing his seat in the 1945 election, he joined the Labour Party. He tried to get back into Parliament in 1948 but was unsuccessful.

Writer

Harold Nicolson's wife, Vita, encouraged him to write. He published a biography of the French poet Paul Verlaine in 1921. He also wrote about other famous writers like Tennyson, Byron, and Swinburne. In 1933, he wrote a book called Peacemaking 1919, about the Paris Peace Conference.

In 1932, he wrote a novel called Public Faces. This book was very forward-thinking. It imagined a future where Britain used rocket planes and an atomic bomb to keep world peace. It even mentioned a multi-megaton bomb and the importance of the Persian Gulf.

After his political career ended, Harold continued to write a lot. He wrote books, book reviews, and a weekly column for The Spectator magazine.

His personal diary is very famous. It gives a great look into British political history from the 1930s to the 1950s. Harold was close to many important political figures. These included Ramsay MacDonald, David Lloyd George, Anthony Eden, and Winston Churchill. His diaries show the daily events and inner workings of power during those times.

Family Life

Harold and Vita had two sons: Benedict, who became an art historian, and Nigel, who became a politician and writer. Nigel later published his parents' letters and Harold's diaries.

In 1930, Vita Sackville-West bought Sissinghurst Castle in Kent. There, Harold and Vita created the beautiful gardens that are now managed by the National Trust.

Honors and Recognition

In 1953, Harold Nicolson was made a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO). This was a reward for writing the official biography of King George V.

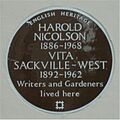

There is a special blue plaque on their house in Ebury Street, London. This plaque remembers both Harold Nicolson and his wife, Vita Sackville-West.

Works

- Paul Verlaine (1921)

- Sweet Waters (1921)

- Tennyson: Aspects of His Life, Character and Poetry (1923)

- Byron: The Last Journey (1924)

- Swinburne (1926)

- Some People (1927)

- The Development of English Biography (1927)

- Swinburne and Baudelaire: The Zaharoff Lecture (1930)

- Portrait of a Diplomatist: Being the Life of Sir Arthur Nicolson, First Lord Carnock, and a Study of the Origins of the Great War (1930)

- People and Things: Wireless Talks (1931)

- Public Faces: A Novel (1932)

- Peacemaking 1919 (1933)

- Curzon: The Last Phase, 1919–1925: A Study in Post-War Diplomacy (1934)

- Dwight Morrow (1935)

- Politics in the Train (1936)

- Helen's Tower (1937)

- Small Talk (1937)

- Diplomacy (1939)

- Marginal Comment (January 6 – August 4, 1939) (1939)

- Why Britain is at War (1939)

- The Desire to Please: The Story of Hamilton Rowan and the United Irishmen (1943)

- The Poetry of Byron: The English Association Presidential Address, August 1943 (1943)

- Friday Mornings 1941–1944 (1944)

- England: An Anthology (1944)

- Another World Than This: An Anthology (1945) edited with Vita Sackville-West

- The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity: 1812–1822 (1946)

- Comments 1944–1948 (1948)

- Benjamin Constant (1949)

- King George V (1952)

- The Evolution of Diplomacy (1954)

- The English Sense of Humour and other Essays (1946)

- Good Behaviour, being a Study of Certain Types of Civility (1955)

- Sainte-Beuve (1957)

- Journey to Java (1957)

- The Age of Reason (1700–1789) (1960)

- Tennyson: Aspects of his Life, Character and Poetry (1960)

- Monarchy (1962)

- Diaries and Letters 1930–39; Diaries and Letters 1939–45; Diaries and Letters 1945–62 (1966–68) - edited by Nigel Nicolson

Images for kids

See also

- List of Bloomsbury Group people

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |