Mixtec culture facts for kids

|

|

| Religion | Mixtec religion |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Present day Mexico

|

| Period | 1500 BC |

| Dates | 1500 BC - 1523 AD |

The Mixtec culture (also known as the Mixtec civilization) was an ancient group of people in pre-Hispanic Mexico. They were the ancestors of today's Mixtec people. They called themselves ñuu Savi, which means "people of the rain". This culture began around 1500 BC and lasted until the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s. Their homeland was a mountainous area called La Mixteca. This region is found in parts of the Mexican states of Puebla, Oaxaca, and Guerrero.

The Mixtec culture has one of the longest histories in Mesoamerica. It started when people speaking Otomanguean languages developed unique traditions in Oaxaca. The Mixtecs shared many customs with their neighbors, the Zapotec. Both groups even called themselves "people of the rain" or "people of the cloud". Over time, the Mixtecs and Zapotecs grew differently. Zapotecs built large cities like Monte Albán. Mixtecs lived in many smaller towns across their mountain valleys. Mixtec goods were traded far and wide, even reaching the Olmec heartland.

During the Classic period, great cities like Teotihuacan and Monte Albán influenced the Mixtec region. In areas like the Lowland Mixteca, cities such as Cerro de las Minas grew. Stone carvings found there show a writing style that mixed ideas from Monte Albán and Teotihuacan. Zapotec influence was also seen in many urns, often showing the Old God of Fire. Later, the Lowland Mixteca culture declined, just like Teotihuacan and Monte Albán. Many old customs were forgotten by the 7th and 8th centuries.

The Mixtec culture truly thrived from the 13th century onwards. A powerful leader named Eight Deer Jaguar Claw united many Mixtec states. He founded the kingdom of Tututepec and expanded his power through military campaigns. He even allied with a Nahua-Toltec lord from Cholula. Eight Deer's rule ended when he was killed by the son of a noblewoman he had previously assassinated.

In the later Postclassic period, Mixtec and Zapotec states often formed alliances through marriage. However, they also became rivals. Despite this, they worked together to fight off the Mexica (Aztec) invaders. The Aztec Empire conquered some powerful Mixtec states, making them pay tribute. But Tututepec remained independent. It even helped the Zapotecs resist in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. When the Spanish arrived, many Mixtec lords chose to become vassals of Spain. This allowed them to keep some of their traditions. Others resisted but were defeated.

Contents

The Mixtec Land

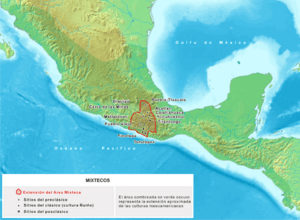

The Mixtec people lived in southern Mexico. Their historical land, called La Mixteca, covers over 40,000 square kilometers. It includes southern Puebla, eastern Guerrero, and western Oaxaca. The Mexica called it Mixtecapan, meaning "Country of the Mixtecs". In the old Mixtec language, it was called Ñuu Dzahui. This name means "Country of the Rain People".

The Mixtecs never formed one single country that included all their villages. The largest political group was under Eight Deer Jaguar Claw in Tilantongo. Geographically, the Mixtec land is very diverse. It has large mountain ranges like the Sierra Mixteca. Its exact borders are hard to define. Culturally, La Mixteca is where all the people called Mixtec lived. They sometimes lived alongside other groups who spoke similar languages.

The Mixtec region is usually divided into three main areas:

- Lowland Mixteca: This is in northwestern Oaxaca and southeastern Puebla. It is hotter and drier.

- Highland Mixteca: This area is in northwest Guerrero and western Oaxaca. It is mountainous and cooler.

- Coastal Mixteca: This part is along the Pacific coast, in Oaxaca and Guerrero.

Mixtec Origin Story

Mixtec myths are similar to other Mesoamerican stories. Like the Mexica and Maya, Mixtecs believed they lived in the "era" of a Fifth Sun. Before their time, the world was created and destroyed many times. At first, everything was mixed up. Two powerful spirits, Uno Venado-Serpiente de Jaguar and Uno Venado-Serpiente de Puma, flew in the air. They were like the "Two Lords" who represent balance in the universe.

These two gods separated light from dark, and land from water. They created four other gods who made humans from corn. A legend says a tree gave birth to a man named Nueve Viento. He fought the sun, the lord of La Mixteca. They shot arrows and rays at each other until sunset. The sun fell wounded and hid behind the mountains. Nueve Viento feared the sun would return. So, he brought his people to settle the land he had won. They quickly planted cornfields. When the sun rose the next day, it could not take back the land. This is how the Mixtecs became owners of the region.

The Mixtecs believed they came from the sons of the Apoala tree. Their main god was Dzahui, the god of rain. He was the protector of the Mixtec people. Another important god was Nueve Viento-Coo Dzahui. He was a hero who taught them about farming and civilization.

Mixtec History

The Mixtecs are one of the oldest groups in Mesoamerica. Their language is part of the Mixtec group, related to Zapotec and Otomi. People have lived in La Mixteca since about 5000 BC. But the Mixtec culture really began when farming developed. Around 3000 BC, the first farming villages appeared. They grew chili, corn, beans, and squash. By 1000 BC, towns grew and joined a large trade network across Mesoamerica. Like most Mesoamerican societies, the Mixtecs were not one unified country. They were small states, each with several towns.

We know less about Mixtec history during the early periods. But we know more about their later flourishing. During this time, Tututepec expanded greatly. It was founded by Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. It came to control a large area and made alliances with other states. When the Spanish arrived in the 1500s, most of La Mixteca was taken over peacefully. Only a few places, like Tututepec, resisted with force.

Early Mixtec Times (Preclassic Period)

The first settled villages in La Mixteca appeared around 1600 BC. These early farming communities were similar to those in other parts of Mesoamerica. However, Mixtec towns were smaller than the large early cities in the Oaxaca Valley. Mixtec settlements were small farming communities. But they were already part of a trade network with other Mesoamerican groups.

For example, Mixtec pottery shows influence from the Olmec style. Olmec-style figures have been found in Mixtec sites like Huamelulpan. Also, Mixtec pottery has been found in the Olmec heartland. This shows they traded with each other. In these early times, Mixtec society was not very divided. Houses were similar, and there were few differences in wealth.

By the end of the Middle Preclassic (around 500 BC), some Mixtec towns grew larger. Monte Negro and Huamelulpan became home to thousands of people. In the Lowland Mixteca, Cerro de las Minas also began to grow. During this time, Mixtec society became more organized. Public buildings appeared in towns like Yucuita. This shows that the first small states were forming. These states controlled small areas, often less than 100 square kilometers.

The Zapotec state of Monte Albán also grew at this time. Monte Albán was much larger and expanded its control. Mixtec and Zapotec cultures influenced each other. For example, Mixtec towns produced pottery similar to Zapotec pottery. Zapotec writing has even been found in Mixtec areas. But there is no proof that Monte Albán ruled the Mixtecs politically. These influences likely came from shared cultural development.

Classic Mixtec Times

The Classic Period in Mixtec culture lasted from about 1 AD to the 8th or 9th century. During this time, large cities appeared across Mesoamerica. These cities had specialized areas and clear social classes. The influence of Teotihuacan was felt everywhere. Trade between different towns became stronger.

In La Mixteca, political power shifted during the Classic period. Old centers like Yucuita were replaced by new ones like Yucuñudahui. However, some towns like Huamelulpan declined. Population grew across the Highland Mixteca. New towns appeared in valleys and mountains.

Unlike the Zapotecs, who had one main capital at Monte Albán, the Mixtecs were organized into many small city-states. These rarely had more than 12,000 people. Mixtec society was clearly divided into classes. Their religion also became more defined, with a strong focus on the god Dzahui, the god of rain.

In the Lowland Mixteca, a unique culture called ñuiñe developed. Its main center was Cerro de las Minas. This city had urban features similar to Highland Mixteca cities. It was built around several small plazas, not one large one. The city was built on terraces, with many stairways. Cerro de las Minas had stone carvings with a special writing system called ñuiñe. This writing was very similar to Zapotec writing.

Other ñuiñe sites include San Pedro and San Pablo Tequixtepec. Characteristic ñuiñe art includes "colossal heads" and urns showing the god of fire. These urns were similar to Zapotec ones. During the Classic period, Lowland Mixteca had the most important political centers. Many cities were built in places that were easy to defend. This suggests there were conflicts between states.

Around the 7th century, many Mesoamerican cities faced crises. Teotihuacan and Monte Albán declined. Mixtec states also faced these problems. The ñuiñe culture disappeared. Many important cities were abandoned. However, some cities like Cerro Jazmín and Tilantongo continued to be inhabited.

Later Mixtec Times (Postclassic Period)

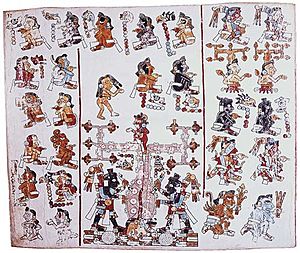

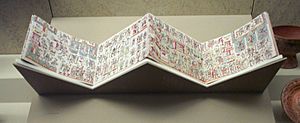

The Postclassic period is the best-known time in Mixtec history. This is because of old stories and special books called codices that survived. In Mesoamerica, this period saw the rise of powerful warrior states. Mixtec cities had been protected by walls for a long time. But now, military activity became even more important.

By the late 700s, the ñuiñe style in Lowland Mixteca faded. It was replaced by the style seen in the Mixtec codices. A new art style appeared, along with new beliefs. The population in La Mixteca grew a lot, especially in Highland Mixteca. The number of towns doubled. These towns were organized into small states that often fought each other. Each state had a main city that ruled over smaller settlements. This system of rulers and their subjects was always part of Mixtec history.

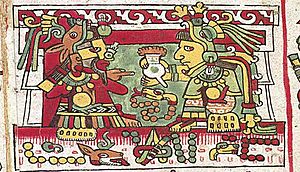

From the Postclassic period, Mixtecs had more contact with other groups in Oaxaca. This was true even with groups who spoke different languages. The relationship between Mixtecs and Zapotecs became very close. They traded and formed political alliances. Noble families from both groups often married each other. For example, the Codex Nuttall tells of a Mixtec lord marrying a Zapotec noblewoman. Their son became a powerful ruler who united Mixtec and Zapotec armies.

Many Zapotec cities show signs of Mixtec presence. This includes Monte Albán, where a famous treasure from Tomb 7 was found. Some believe this shows Mixtec control over the Zapotecs. Others think it means Mixtec art was simply popular and used by Zapotec nobles. Besides Monte Albán, other cities like Mitla and Zaachila also have Mixtec art or objects.

Mixtec Settlement of the Coast

The coast of Oaxaca was originally home to Zapotec-speaking people. But around the 10th or 11th century, Mixtecs began to move there. This caused a shift in power. Zapotec towns came under the rule of Mixtec nobles. So, Mixtec chiefdoms on the coast, like Tututepec, had people from different ethnic groups. Tututepec grew rapidly between the 800s and 900s. From the 11th century, Tututepec became very important. It was the first home of Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. He was a Mixtec lord who united many states and controlled a huge area.

The Kingdom of Eight Deer Jaguar Claw

The Mixtec people were usually divided into many small states. But between the 11th and 12th centuries, many of these states united under Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. He was a very important figure in Mesoamerican history. He gained power in La Mixteca and formed ties with other groups, especially the Nahua people.

Eight Deer was not directly in line to rule Tilantongo. But he gained fame in military battles. In 1083, he took the throne of Tututepec on the Pacific coast. Later, he allied with the Toltecs. He received a special title from them. In 1097, Eight Deer met with Cuatro Jaguar, a key ally.

This alliance helped Eight Deer become ruler of Tilantongo. He removed all other heirs to the throne. He conquered many important areas, including Lugar del Bulto de Xipe. In 1101, Eight Deer defeated its defenders. He sacrificed their sons. This added more lands to his growing kingdom.

During his rule in Tilantongo, Eight Deer conquered about 100 Mixtec states. He also formed many alliances through marriages. He had several wives from noble families. His first son was born in 1109. Eight Deer was killed in 1115. He was defeated by a group of rebel lords. These rebels were led by Cuatro Viento, the only son of a noble family Eight Deer had tried to eliminate. After Eight Deer's death, his kingdom broke apart into many smaller states again.

The Mexica Conquer Mixtec Lands

After Eight Deer's death, his sons inherited some important lordships. Other Mixtec cities regained their independence. The old system of small, often warring, states returned. At this time, La Mixteca was very rich. It traded luxury goods like pottery, feather art, and gold. It also traded food from different climates.

La Mixteca was located between central Mexico and the Mesoamerican southeast. This made it important to the Triple Alliance (Mexica, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan). By the late 1400s, much of La Mixteca was under Mexica control. Important cities like Coixtlahuaca became centers for collecting tribute. The Mexica wanted to control trade routes. They tried to conquer the Mixtec coast and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. But they were defeated by an alliance of Zapotecs and Mixtecs. A major victory for the Mixtec-Zapotec alliance was at Guiengola.

The Spanish Arrive

When the Spanish arrived in Veracruz in 1519, different groups reacted differently. Some saw the Spanish as a chance to be free from Aztec rule. After the fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan in 1521, the Spanish attacked other groups, including the Mixtecs. But most Mixtecs made agreements with the Spanish. This allowed them to keep many of their traditions, like their language, trade, and farming methods. Only a few parts of La Mixteca, like Tututepec, fought against the Spanish.

Mixtec Society

Family and Kinship

In the later Mixtec period, families had a "Hawaiian-type" kinship system. This meant that children could inherit property and titles from both their mother and father. Women could also hold high positions of power. Over 950 noblewomen are mentioned in old Mixtec codices. In this system, a person would call their father and all their male uncles by the same term. They would also call their mother and all their aunts by the same term. This meant their brothers and their cousins (children of uncles and aunts) were all called by the same word.

Social Groups

Mixtec society was very structured. These differences appeared over a long time, starting around 1600 BC. At first, there were not many differences between people's homes. Goods were limited, and it was hard to tell the homes of the rich from others.

As cities grew, society became more divided. This was supported by beliefs and alliances among the nobles. The ñuiñe style in Lowland Mixteca showed how rulers wanted to highlight their differences from common people. Spanish records describe several groups in Mixtec society:

- yyá: The lord or ruler of a Mixtec state.

- dzayya yya: The Mixtec nobility, who were like the king.

- tay ñuu: Free people.

- tay situndayu: People who worked the land and paid tribute.

- tay sinoquachi and dahasaha: Servants and slaves.

It was very hard to move up in society. Nobles (dzayya yya) usually married other nobles. This kept their power and wealth within their group. They also married nobles from other Mixtec villages. This created a complex network of alliances that helped keep order. Free people (tay ñuu) owned themselves and their work. They worked on land that was owned by the community. The tay situndayu had lost control of their work and had to pay tribute to the nobles. Servants and slaves had the fewest rights.

How They Ruled

Mixtec political life was often divided into many small states. These states controlled small areas and often fought each other. From early times, towns within a state had a clear ranking. The most important towns had more large buildings. The power of each town could change over time. For example, Yucuita was replaced by Yucuñudahui as a main center.

The ñuu (meaning "people" or "community") was the basic unit of Mixtec politics. A ñuu could be the main city of a state or a smaller town. Mixtec states were often formed by a yuhuitayu. This was a union of two noble families through marriage. Rulers used many strategies to keep their power. Marriages between noble families were common. These alliances helped connect powerful families across the Mixtec land. They even married nobles from other groups, like the Zapotecs.

Mixtec Warriors

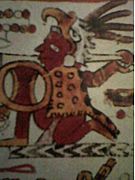

The Mixtecs had their own ways of war. They invented weapons, conquered lands, and defended their territory. They often fought with other Mixtec cities or Zapotec towns. The most famous Mixtec warrior was Eight Deer. His battles are told in the Codex Nuttall.

The codices show us the weapons and clothes of Mixtec warriors:

- Long-range weapons: They used bows and arrows with tips made of obsidian or flint. They also used the atlatl, a spear-thrower common in Mesoamerica.

- Close-range weapons: For close combat, Mixtecs used clubs and spears. One common weapon was a wooden stick bent at a 90-degree angle. It had sharp stone blades on top. This weapon was special to the Mixtec and Zapotec areas.

- Warrior clothing: Warriors in the codices wear animal costumes. These include jaguar skins, eagle-headed helmets, and deer skins. Animal uniforms were common in Mesoamerica.

Mixtec Economy

Farming and Food

Like other Mesoamerican groups, the Mixtecs relied on agriculture for food. The varied landscape of La Mixteca meant they grew different crops. The most important crop was maize (corn). They also grew different kinds of beans, chili, and squash. In warmer areas, they grew cotton and cocoa.

The Mixtec land was mountainous and often dry. Farming was better in the valleys of Highland Mixteca. To grow more food, they built terraces on mountain slopes. These terraces, called coo yuu, helped create flat land for crops. They also helped save water. Farmers today say these terraces can produce good corn harvests after a few years. The Mixtecs also used "slash-and-burn" farming. They cleared plants and burned them to fertilize the soil. This caused a lot of deforestation in the region.

Other Economic Activities

Few animals were domesticated in Mesoamerica. The turkey (guajolote) and the xoloitzcuintle dog were two of them. Both were eaten in small amounts. In La Mixteca, they also raised cochineal. This insect lives on nopal cacti. It was used to make a bright red dye called carmine. Cochineal farming was a main activity until the 1800s, when chemical dyes appeared.

Besides farming, Mixtecs also hunted, gathered, and fished. The diverse climates in La Mixteca meant many states could grow most of their own food.

The Mixtecs were part of a large Mesoamerican trade network. They traded farm products and cochineal. They also traded valuable materials and finished goods. They were known for producing minerals like magnetite. Early Mixtec pottery was traded with the Olmecs.

Mixtec Culture

Language and Writing

Before the Spanish arrived, Mixtecs spoke many different kinds of Mixtec language. These languages were related to Trique. The different Mixtec languages developed over time. For example, the coastal Mixtec language separated from the highland Mixtec around the 10th or 11th century. This matches when Mixtecs moved to the coast.

Spanish priests later created a written form of the Mixtec language. They wrote the first grammar book for the language spoken in Highland Mixteca. This language was probably used for communication across the region.

Like other Mesoamerican groups, the Mixtecs had their own written stories. They used a pictographic writing system. This means they used pictures to represent words and ideas. Several ancient Mixtec books, called codices, still exist. These include the Codex Nuttall, Selden, Vindobonensis, Becker I, and Colombino. Most of these are in museums in Europe. These codices helped people remember and tell stories. The pictures could be "read" aloud by those who understood them.

Mixtec Writing System

The Mixtecs developed their own writing system. The first signs of writing in the Mixtec area are from Highland Mixteca, around 500 BC. Some stone carvings in Huamelulpan have dates and names of leaders. These early writings were in the Zapotec system. Later, the ñuiñe script developed in Lowland Mixteca. It was also similar to Zapotec writing.

Around the 9th century, the Mixtec writing system appeared. It was part of a larger art style called Mixteca-Puebla style. This writing used pictures, but also had symbols for words and ideas. Mixtec writing helped preserve their beliefs and history. Alfonso Caso showed that the codices in the Mixtec group were made by Mixtecs, not Mexica or Maya.

Mixtec Religion

The ancient Mixtecs had an animist religion. This means they believed spirits lived in nature. Their religion shared many features with other Mesoamerican religions. They believed in a main dual god who created the world. They also believed the world had been created and destroyed many times.

According to the Codex Vindobonensis, Uno Venado-Serpiente Jaguar and Uno Venado-Serpiente Puma created the first beings, the ñuhu. These ñuhu helped organize the world. They were the spirits of fire, wind, water, earth, plants, and animals. When the Sun rose, these beings turned to stone. But some hid in caves and survived. Because of this, Mixtecs worshipped mountains and caves. Some caves, like those in Chalcatongo, were important pilgrimage sites.

The main god of the Mixtecs was Dzahui, the god of rain. Rain was so important that the Mixtecs called themselves "people of the rain". Dzahui is similar to the god Tlāloc from central Mesoamerica. His worship dates back to around 500 BC.

In the Lowland Mixteca, people also worshipped the old god of fire, Huehuetéotl. This god was worshipped throughout Mesoamerica. The name Ñuiñe (Lowland Mixteca) means "Hot Land," showing the importance of fire. The fire god was shown as an old man holding a large incense burner. In Cerro de las Minas, figures of the fire god hold incense burners or tobacco pipes. The fire cult declined in Lowland Mixteca as the ñuiñe culture faded.

Mixtec religious leaders had a clear structure. High priests were called yaha yahui (Eagle-Fire Serpent). Mixtecs believed these priests could turn into animals. They were feared for their power over the spirit world.

Mixtec Art

Ancient Mixtec art was closely linked to religion. Many beautiful pieces were used in temples or for rituals. Other objects were used by nobles in their daily lives. Most Mixtec art we know today is from the Postclassic Period (10th-16th centuries). This was a time of great artistic achievement. Mixtec artists were known for their detailed and precious small works. Their architecture and stone sculptures were simpler compared to their neighbors, the Zapotecs.

Mixtec buildings were relatively simple. Temples were on pyramid-shaped platforms with stairs. Other buildings were around large plazas. Homes for common people were made of less durable materials like mud and palm.

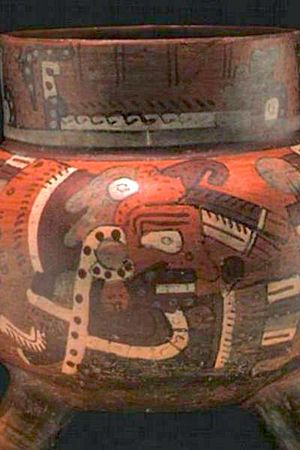

Many Mixtec art pieces are pottery. Some of the oldest show Olmec and Zapotec influences. The ñuiñe style in Lowland Mixteca also shows strong Zapotec and Teotihuacan influences. Representations of the fire god were popular. Other ñuiñe pieces include large stone heads.

The Postclassic Period was the peak of Mixtec pottery. A new art style, called Mixteca-Puebla, spread across Mesoamerica. Mixtec pottery from this time is very fine and richly decorated. It is thin, reddish or brown, and has a shiny finish. The surfaces were decorated with themes and colors like those in the Mixtec codices. This colorful pottery was for the elite. Pieces have been found outside the Mixtec region, showing they were traded.

Mixtec sculpture also exists. Stone slabs (stelae) have been found with dates and names. These show Teotihuacan and Zapotec influences. Some lintels from ñuiñe sites decorated building entrances. However, the best Mixtec sculptures are small, detailed pieces. They carved objects from bone, wood, rock crystal, and precious stones like jade and turquoise. These were so beautiful that one expert compared them to "the best Chinese carvings." Many of these objects were found in tombs, like Tomb 7 at Monte Albán.

Mixtec Clothing

For Mixtec Women

Mixtec women wore a special outfit. It included a white blouse embroidered around the neck and sleeves. They also wore a full skirt made of poplin fabric with printed flowers. This skirt had three colored ribbons, symbolizing the three Mixtec regions. A bundle of seven bright ribbons hung on the left side. Underneath, they wore a white sash. A black shawl was used as a belt, showing if a woman was married or a mother. A scarf around the neck was used to wipe sweat, showing she was hardworking. They wore necklaces made of colorful paper beads. For their hair, they braided it with four colored ribbons and added a red carnation. They wore huaraches (sandals) with two white straps.

For Mixtec Men

Mixtec men wore white breeches and a white shirt. They had a colorful scarf (paliacate) at their waist and another around their neck. Over their shoulder, they carried a wool blanket. They wore a palm hat with a wide brim, in a style called "four stones." They also wore huaraches (sandals) with three white straps.

Metalwork

Working with metals (metallurgy) developed late in Mesoamerica. Some believe this was a choice, as Mesoamerica was a "stone civilization." The earliest metal objects are from the end of the Classic period. This technology came from Central and South America. By the time of the Spanish Conquest, the Tarascans were skilled at working with copper and other metals. They made tools and beautiful objects.

The Mixtecs in Oaxaca also started working with metals during the Postclassic period. Copper axes have been found, showing they made tools, not just ornaments. The most famous Mixtec metal pieces are made of gold. Mesoamericans thought gold was "excrement of the gods." In the Postclassic, it became a symbol of the Sun. So, some of the most beautiful Mixtec gold pieces combine gold with turquoise, the "solar stone." An example is the Shield of Yanhuitlán.

Gold objects were only for rulers. Mixtec rulers wore many gold items, along with jade, turquoise, feathers, and fine textiles. When the Spanish arrived, many gold pieces were melted down into bars. Some were sent to Europe and survived. Many pieces have been found in archaeological sites, especially at Zaachila and Tomb 7 of Monte Albán. Tomb 7 had the largest collection of gold and silver found in one place in Mesoamerica.

See also

In Spanish: Cultura mixteca para niños

In Spanish: Cultura mixteca para niños

- Mixtec

- Mixtec language

- Mixtec writing

- Ocho Venado

- Mesoamerica

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |