Chinese garden facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chinese garden |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

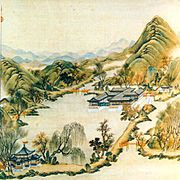

This picture of the Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai (created in 1559) shows all the elements of a classical Chinese garden – water, architecture, vegetation, and rocks.

|

|||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國園林 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国园林 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | China Garden-Woods | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Chinese classical garden | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國古典園林 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国古典园林 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | China Classical Garden-Woods | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

A Chinese garden is a special kind of garden that has been developed over more than three thousand years. These gardens include huge ones built for Chinese emperors and their families. These royal gardens were made for fun and to show off wealth. There were also smaller, more private gardens. Scholars, poets, and former government officials built these. They used them for quiet thinking and to escape the busy world.

Chinese gardens are like miniature landscapes. They are designed to show how humans and nature should live in harmony. The art of Chinese gardens combines many things. These include buildings, beautiful writing, art, sculpture, and stories. They also include gardening itself and other Chinese arts. These gardens show what Chinese people find beautiful. They also reflect deep ideas about life and philosophy.

Some famous Chinese gardens are even on the World Heritage List by UNESCO. These include the Chengde Mountain Resort and the Summer Palace, which were royal gardens. Also on the list are several Classical Gardens of Suzhou in Jiangsu Province, which were private gardens. Many important parts make up a Chinese garden. A Moon Gate is one of these unique features.

A typical Chinese garden is usually surrounded by walls. Inside, you'll find one or more ponds, interesting rock formations, trees, and flowers. There are also many halls and pavilions. Winding paths and zig-zag walkways connect everything. As visitors move through the garden, they see a series of carefully planned scenes. It's like watching a landscape painting unroll before your eyes.

Contents

History of Chinese Gardens

Early Gardens: The Beginnings

The first Chinese gardens we know about were built in the Yellow River valley. This was during the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC). These early gardens were large, walled-off parks. Kings and nobles used them for hunting. They also grew fruits and vegetables there.

Old writings from this time show three Chinese words for garden. These were you, pu, and yuan. You was a royal garden where animals were kept. Pu was a garden for plants. Later, during the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), the word yuan became the general word for all gardens. The old symbol for yuan looks like a small picture of a garden. It has a square for a wall, symbols for buildings, a small square for a pond, and a symbol for plants.

A famous royal garden from the Shang dynasty was the Terrace, Pond and Park of the Spirit. King Wenwang built it west of his capital city, Yin. The Classic of Poetry described this park:

- The King walks in the Park of the Spirit.

- Deer are kneeling on the grass, feeding their babies.

- The deer are beautiful and bright.

- Clean cranes have bright white feathers.

- The King walks to the Pond of the Spirit.

- The water is full of fish, wiggling around.

Another early royal garden was Shaqui, or the Dunes of Sand. The last Shang ruler, King Zhou (1075–1046 BC), built it. It had a raised earth platform, or tai, in the middle of a large park. This platform was used for viewing. The Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji), an old Chinese book, described it. One famous part was the Wine Pool and Meat Forest. A big pool, large enough for small boats, was built. It had smooth, oval stones from the seashore inside. The pool was then filled with wine. A small island was built in the middle. Trees were planted there, with roasted meat hanging from their branches. King Zhou and his friends would float in boats, eating meat from the trees. Later Chinese thinkers said this garden showed bad taste and too much luxury.

During the Spring and Autumn period (722–481 BC), in 535 BC, the Terrace of Shanghua was built. It had fancy palaces. King Jing of the Zhou dynasty built it. In 505 BC, an even grander garden, the Terrace of Gusu, was started. It was on the side of a mountain. It had terraces connected by walkways. There was also a lake where boats shaped like blue dragons sailed. From the highest terrace, you could see all the way to Lake Tai, a very large lake.

The Legend of the Isle of the Immortals

An old Chinese legend greatly influenced early garden design. In the 4th century BC, a story in the Classic of Mountains and Seas described a peak called Mount Penglai. It was on one of three islands in the Bohai Sea, between China and Korea. This island was the home of the Eight Immortals. On this island were palaces of gold and silver, with jewels on the trees. There was no pain or winter. Wine glasses and rice bowls were always full. Eating the fruits there gave eternal life.

In 221 BC, Ying Zheng, the King of Qin, united China under the Qin Empire. He ruled until 210 BC. He heard the legend of the islands. He sent people to find them and bring back the elixir of immortal life, but they failed. At his palace near his capital, Xianyang, he built a garden with a large lake called Lanchi gong. On an island in the lake, he made a copy of Mount Penglai. This showed his search for paradise. After he died, the Qin Empire fell in 206 BC. His capital and garden were destroyed. But the legend kept inspiring Chinese gardens. Many gardens have islands or a single island with a fake mountain. These represent the island of the Eight Immortals.

Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD)

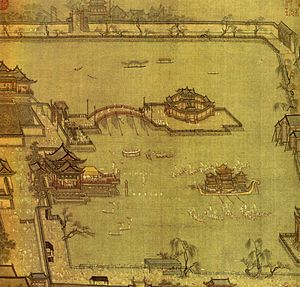

Under the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), a new capital was built at Chang'an. Emperor Wu built a new imperial garden. It had features of both plant and animal gardens, plus traditional hunting grounds. He was inspired by another Chinese story about the Isles of the Immortals, called Liezi. He created a large artificial lake, the Lake of the Supreme Essence. It had three artificial islands in the middle, representing the three Isles of the Immortals. The park was later destroyed. But its memory continued to inspire Chinese garden design for hundreds of years.

Another important garden from the Han period was the Garden of General Liang Ji. It was built under Emperor Shun (125–144 AD). Liang Ji used his wealth to build a huge garden. It had artificial mountains, valleys, and forests. It was filled with rare birds and tamed wild animals. This was one of the first gardens that tried to copy nature in an ideal way.

Gardens for Poets and Scholars (221–618 AD)

After the Han dynasty fell, China had a long time of political trouble. Buddhism came to China with Emperor Ming (57–75 AD). It spread quickly. By 495 AD, the city of Luoyang, capital of the Northern Wei dynasty, had over 1,300 temples. Most were in former homes. Each temple had its own small garden.

During this time, many former government officials left the court. They built gardens where they could escape the world. They focused on nature and literature. One example was the Jingu Yuan, or Garden of the Golden Valley. Shi Chong (249–300 AD), a rich former official, built it in 296 AD. It was ten kilometers northeast of Luoyang. He invited thirty famous poets to a party in his garden. He wrote about it himself:

I have a country house at the torrent of the Golden Valley...where there is a spring of pure water, a luxuriant wood, fruit trees, bambo, cypress, and medicinal plants. There are fields, two hundred sheep, chickens, pigs, geese and ducks...There is also a water mill, a fish pond, caves, and everything to beguile the eye and please the heart....With my literary friends, we took walks day and night, feasted, climbed a mountain to view the scenery, and sat by the side of the stream.

This visit led to a famous collection of poems, Jingu Shi. This started a long tradition of writing poetry in and about gardens.

The poet and calligrapher Wang Xizhi (307–365) wrote a famous piece called the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion. This introduced a book about a poetry event at a place called the "Orchid Pavilion." This park had a winding stream. He gathered famous poets and seated them by the stream. Then he put cups of wine in the stream and let them float. If a cup stopped by a poet, they had to drink it and then write a poem. Gardens with floating cups (liubei tang), small pavilions, and winding streams became very popular. This happened in both royal and private gardens.

The Orchid Pavilion inspired Emperor Yang (604–617) of the Sui dynasty. He built his new imperial garden, the Garden of the West, near Hangzhou. His garden had a winding stream for floating wine glasses. It also had pavilions for writing poetry. He used the park for plays too. He launched small boats on his stream with moving figures showing Chinese history.

Tang Dynasty (618–907): The First Golden Age

The Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) is seen as the first golden age for classical Chinese gardens. Emperor Xuanzong built a grand imperial garden. It was called the Garden of the Majestic Clear Lake, near Xi′an. He lived there with his famous concubine, Consort Yang.

Painting and poetry became very advanced. Many new gardens, big and small, filled the capital city, Chang'an. These new gardens were inspired by old legends and poems. There were shanchi yuan, gardens with fake mountains and ponds. These were inspired by the legend of the immortal islands. There were also shanting yuan, gardens with copies of mountains and small viewing houses, or pavilions. Even regular homes had tiny gardens in their courtyards. These had small mountains made of clay and tiny ponds.

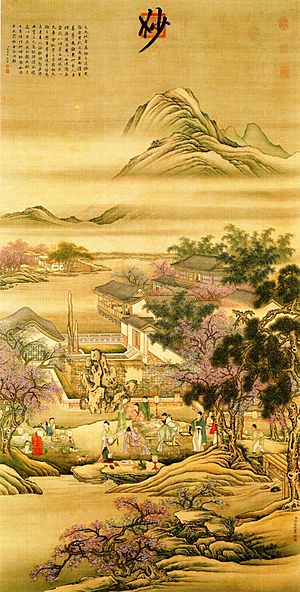

These classical Chinese gardens, or scholar's gardens (wenren yuan), inspired and were inspired by Chinese poetry and painting. A great example was the Jante Valley Garden of the poet-painter Wang Wei (701–761). He bought a ruined house of a poet near a river and a lake. He created twenty small landscape scenes in his garden. They had names like the Garden of Magnolias and the Kiosk in the Heart of the Bamboos. He wrote a poem for each scene. He also asked a famous artist to paint scenes of the garden on his villa walls. After leaving government work, he spent his time boating on the lake, playing music, and writing poems.

During the Tang dynasty, growing plants became very advanced. Many plant types were brought in, tamed, moved, and grafted. The beauty of plants was very important. Many books on how to classify and grow plants were published. The capital, Chang'an, was a very diverse city. It had diplomats, merchants, and students. They carried descriptions of the gardens all over Asia. The strong economy of the Tang dynasty led to more classical gardens being built across China.

The last great garden of the Tang dynasty was the Hamlet of the Mountain of the Serene Spring (Pingquan Shanzhuang). Li Deyu, a Grand Minister, built it east of Luoyang. The garden was huge, with over a hundred buildings. But it was most famous for its collection of unusually shaped rocks and plants. Its creator collected them from all over China. Rocks with strange shapes, known as Chinese Scholars' Rocks, became a key part of Chinese gardens. They often looked like parts of mountains.

Song Dynasty (960–1279)

The Song dynasty had two periods: Northern and Southern. Both were known for building famous gardens. Emperor Huizong (1082–1135) was a skilled painter of birds and flowers. He was also a scholar. He added parts of scholar gardens to his grand imperial garden. His first garden, The Basin of the Clarity of Gold, was a fake lake with terraces and pavilions around it. People could visit the garden in spring for boat races and shows on the lake. In 1117, he personally oversaw the building of a new garden. He had rare plants and beautiful rocks brought from all over China, especially prized rocks from Lake Tai. Some rocks were so big that he had to destroy all bridges between Hangzhou and Beijing to move them by water on the Grand Canal. In the center of his garden, he built a fake mountain one hundred meters high. It had cliffs and valleys. He named it Genyue, or "The Mountain of Stability." The garden was finished in 1122. In 1127, Emperor Huizong had to leave the Song capital, Kaifeng. It was attacked by the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty. When he returned (as a prisoner), he found his garden completely destroyed. All the pavilions were burned, and artworks were stolen. Only the mountain remained.

While royal gardens were the most famous, many smaller but beautiful gardens were built in cities like Luoyang. The Garden of the Monastery of the Celestial Rulers in Luoyang was known for its peonies. The whole city came when they bloomed. The Garden of Multiple Springtimes was famous for its mountain views. The most famous garden in Luoyang was The Garden of Solitary Joy (Dule Yuan). The poet and historian Sima Guang (1021–1086) built it. His garden was about 1.5 hectares. In the center was the Pavilion of Study, his library, with five thousand books. To the north was a fake lake with a small island and a fisherman's hut. To the east was a garden of medicinal plants. To the west was a fake mountain with a viewpoint to see the area. Anyone could visit the garden for a small fee.

After Kaifeng fell, the Song dynasty capital moved to Lin'an (today's Hangzhou, Zhejiang). Lin'an soon had over fifty gardens built on the shore of the Western Lake. Another city famous for its gardens was Suzhou. Many scholars, officials, and merchants built homes with gardens there. Some of these gardens still exist today, though most have changed a lot over time.

The oldest Suzhou garden still visible today is the Blue Wave Pavilion. The Song dynasty poet Su Shunqing (1008–1048) built it in 1044. In the Song dynasty, it had a hilltop viewing pavilion. Other lakeside pavilions were added, including a hall for respect, a hall for reciting, and a special pavilion for watching fish. It was changed many times over the centuries, but its main design remains.

Another Song dynasty garden still around is the Master of the Nets Garden in Suzhou. Shi Zhengzhi, a government minister, created it in 1141. It had his library, the Hall of Ten Thousand Volumes, and a garden next to it called the Fisherman's Retreat. It was greatly updated between 1736 and 1796. But it is still one of the best examples of a Song Dynasty Scholar's Garden.

In the city of Wuxi, near Lake Tai and two mountains, there were thirty-four gardens. The Song dynasty historian Zhou Mi (1232–1308) recorded them. The two most famous gardens were the Garden of the North (Beiyuan) and the Garden of the South (Nanyuan). Both belonged to Shen Dehe, a Grand Minister to Emperor Gaozong (1131–1162). The Garden of the South was a classic mountain-and-lake (shanshui) garden. It had a lake with an Island of Immortality (Penglai dao). On it were three large rocks from Taihu. The Garden of the South was a water garden. It had five large lakes connected to Lake Tai. A terrace gave visitors a view of the lake and mountains.

Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368)

In 1271, Kublai Khan started the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty in China. By 1279, he defeated the last Song dynasty resistance. He united China under Mongol rule. He built a new capital where Beijing is today. It was called Dadu, the Great Capital.

The most famous garden of the Yuan dynasty was Kublai Khan's summer palace and garden at Xanadu. The traveler Marco Polo is thought to have visited Xanadu around 1275. He described the garden:

"Around this Palace a wall is built, enclosing 16 miles. Inside the Park there are fountains and rivers and brooks, and beautiful meadows. There are all kinds of wild animals (except fierce ones). The Emperor put them there to feed his falcons and hawks. There are more than 200 falcons alone. The Khan himself goes every week to see his birds. Sometimes he rides through the park with a leopard behind him. If he sees an animal he likes, he lets his leopard chase it. The captured animal is given to feed the hawks. He does this for fun."

This short description later inspired the poem Kubla Khan by the English poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

When he built his new capital at Dadu, Kublai Khan made the artificial lakes bigger. These lakes were created a century earlier by the Jin dynasty. He also built up the island of Oinghua. This created a strong contrast between the curving banks of the lake and garden and the straight lines of what later became the Forbidden City of Beijing. This contrast can still be seen today.

Even with the Mongol invasion, the classical Chinese scholar's garden continued to thrive in other parts of China. A great example is the Lion Grove Garden in Suzhou. It was built in 1342. It got its name from the many strange and fantastic rock formations. These rocks came from Lake Tai. Some were said to look like lion heads. The Kangxi and Qianlong emperors of the Qing dynasty visited this garden several times. They used it as a model for their own summer garden, the Garden of Perfect Splendor, at the Chengde Mountain Resort.

In 1368, forces of the Ming dynasty, led by Zhu Yuanzhang, captured Dadu from the Mongols. They overthrew the Yuan dynasty. Zhu Yuanzhang ordered the Yuan palaces in Dadu to be burned down.

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

The most famous existing garden from the Ming dynasty is the Humble Administrator's Garden in Suzhou. It was built during the time of the Zhengde Emperor (1506–1521). Wang Xianchen, a minor government worker, built it after he retired. He spent his time on his garden. The garden has changed a lot since it was built, but the main part is still there. It has a large pond full of lotus flowers. Buildings and pavilions surround it, designed to offer views of the lake and gardens. The park has an island, the Fragrant Isle, shaped like a boat. It also uses "borrowed view" (jiejing) very well. This means it carefully frames views of nearby mountains and a famous distant pagoda.

Another existing garden from the Ming dynasty is the Lingering Garden, also in Suzhou. It was built during the time of the Wanli Emperor (1573–1620). During the Qing dynasty, twelve tall limestone rocks were added. These rocks symbolized mountains. The most famous was a beautiful rock called the Auspicious Cloud-Capped Peak. It became a main feature of the garden.

A third well-known Ming era garden in Suzhou is the Garden of Cultivation. The grandson of Wen Zhengming, a famous Ming painter, built it during the time of the Tianqi Emperor (1621–27). The garden is built around a pond. It has the Longevity Pavilion on the north side and the Fry Pavilion on the east. There is a dramatic rock garden on the south. The creator's study, the Humble House, is to the west.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1912)

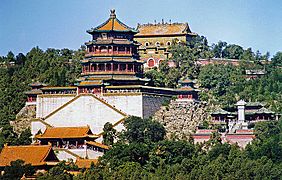

The Qing dynasty was the last dynasty of China. The most famous gardens in China during this time were the Summer Palace and the Old Summer Palace in Beijing. Both gardens became symbols of luxury and elegance. European visitors often described them.

Father Attiret, a French Jesuit and court painter for the Qianlong Emperor, described the Jade Terrace of the Isle of Immortality in the Summer Palace lake:

"That which is a true jewel is a rock or island...which is in the middle of this lake, on which is built a small palace, which contains one hundred rooms or salons...of a beauty and a taste which I am not able to express to you. The view is admirable...

Building and improving these gardens cost a huge amount of money from the royal treasury. Empress Dowager Cixi famously used money meant for modernizing the navy. She used it to restore the Summer Palace and the marble teahouse shaped like a boat on Lake Kunming. Both the Summer Palace and Old Summer Palace were damaged during the Boxer Rebellion and by European armies in the 1800s. But they are now slowly being rebuilt.

Besides these palaces, Qing emperors built a new set of gardens and palaces. This was in the mountains 200 kilometers northeast of Beijing. They built it between 1703 and 1792 to escape the summer heat. It was called the Chengde Mountain Resort. It covered 560 hectares. It had seventy-two different landscape views, copying miniature scenes from all over China. This huge garden has mostly survived.

Famous scholar gardens from this period that still exist include the Couple's Retreat Garden (1723–1736) and the Retreat & Reflection Garden (1885). Both are in Suzhou.

-

The Summer Palace in Beijing today

-

The Long Corridor at the Summer Palace (1750) is 728 meters long. It was built so the emperor could walk through the garden protected from the elements.

-

Keyuan garden in Guangdong Province, (1850)

Designing a Classical Chinese Garden

A Chinese garden was not meant to be seen all at once. Instead, it showed visitors a series of perfectly arranged and framed views. You might see a pond, a rock, a group of bamboo, a blooming tree, or a distant mountain peak.

Some early Western visitors thought imperial Chinese gardens were messy. They seemed crowded with buildings of different styles, without any clear order. But the Jesuit priest Jean Denis Attiret, who lived in China from 1739, noticed something special. He said there was a "beautiful disorder, an anti-symmetry" in the Chinese garden. He wrote, "One admires the art with which this irregularity is carried out. Everything is in good taste, and so well arranged, that there is not a single view from which all the beauty can be seen; you have to see it piece by piece."

Chinese classical gardens varied greatly in size. The largest garden in Suzhou, the Humble Administrator's Garden, was a bit over ten hectares. One-fifth of it was taken up by the pond. But gardens didn't have to be large. Ji Cheng built a garden for Wu Youyu that was just under one hectare. A tour of this garden was only four hundred steps long. Yet, Wu Youyu said it held all the wonders of the province in one place.

The classical garden was surrounded by a wall, usually white. This wall served as a simple background for the flowers and trees. A pond was usually in the center. Many buildings, big and small, were placed around the pond. In the garden Ji Cheng described, buildings took up two-thirds of the space. The garden itself was the other third. In a scholar garden, the main building was often a library or study. It was connected by walkways to other pavilions. These pavilions were observation points for garden features. These buildings also helped divide the garden into separate scenes. The other key parts of a scholar garden were plants, trees, and rocks. All were carefully arranged into small, perfect landscapes. Scholar gardens often used "borrowed scenery" (借景 jiejing). This meant unexpected views outside the garden, like mountain peaks, seemed to be part of the garden itself.

Architecture in Chinese Gardens

Chinese gardens are full of buildings. These include halls, pavilions, temples, walkways, bridges, kiosks, and towers. They take up a large part of the space. The Humble Administrator's Garden in Suzhou has forty-eight structures. These include a home, halls for family events, and eighteen pavilions for viewing different parts of the garden. There are also towers, walkways, and bridges. All are designed to let you see the garden from many different angles. The garden buildings are not meant to stand out. They are designed to blend in with nature.

Classical gardens usually have these types of buildings:

- The ceremony hall (ting), or “room”. This building is used for family parties or ceremonies. It usually has an inner courtyard and is near the entrance.

- The principal pavilion (da ting), or “large room”. This is for welcoming guests, banquets, and celebrating holidays. It often has a porch to provide cool air and shade.

- The pavilion of flowers (hua ting), or “flower room”. This is near the home. It has a back courtyard filled with flowers, plants, and a small rock garden.

- The pavilion facing the four directions (si mian ting), or “four doors room”. This building has walls that can fold or move. This allows for a wide view of the garden.

- The lotus pavilion (he hua ting), or “lotus room”. This is built next to a lotus pond. It's for watching the flowers bloom and enjoying their smell.

- The pavilion of mandarin ducks (yuan yang ting), or “mandarin ducks room”. This building has two parts. One faces north for summer use, with a lotus pond for cool air. The southern part is for winter. It has a courtyard with evergreen pine trees and plum trees, whose blossoms announce spring.

Besides these larger halls and pavilions, gardens have smaller pavilions (also called ting). These are for shelter from sun or rain. They are also for thinking about a scene, reading a poem, enjoying a breeze, or just resting. Pavilions might be placed where you can best see the sunrise, or where moonlight shines on water. They might be where autumn leaves look best, or where rain sounds good on banana leaves. They are sometimes attached to a wall or stand alone at good viewing spots. These spots could be by a pond or on a hill. They are often open on three sides.

The names of pavilions in Chinese gardens often describe the view or feeling they offer:

- The Peak-Worshipping Pavilion (The Lingering Garden) in Suzhou China

- The Hall of Distant Fragrances (Humble Administrator's Garden) in Suzhou China

- The Mountain View Tower (Humble Administrator's Garden) in Suzhou China

- Pavilion of the Moon and Wind (Master of the Nets Garden) in Suzhou China

- Pavilion in the Lotus Breeze (Humble Administrator's Garden) in Suzhou China

- Listening to the Rain Pavilion (Humble Administrator's Garden) in Suzhou China

- Watching the Pines and Appreciating Paintings Hall (Humble Administrator's Garden) in Suzhou China

- Spot of Return for Reading (Lingering Garden) in Suzhou China

- Between the Mountains and the Water Pavilion (The Couple's Retreat Garden) in Suzhou China

- Pavilion Leaning on the Jade (Humble Administrator's Garden) in Suzhou China

- Soft Rain Brings Coolness Terrace (Retreat & Reflection Garden) in Suzhou China

- Lasting Spring and Moon Viewing Tower (Retreat & Reflection Garden) in Suzhou China

Gardens also often have two-story towers (lou or ge). These are usually at the edge of the garden. The lower story is stone, and the upper story is white. It is two-thirds the height of the ground floor. It offers a view from above of parts of the garden or distant scenery.

Some gardens have a beautiful stone pavilion shaped like a boat in the pond. These are called xie, fang, or shifang. They usually have three parts: a small building with winged roofs at the front, a more private hall in the middle, and a two-story structure at the back with a wide view of the pond.

- Courtyards (yuan). Gardens include small, enclosed courtyards. These offer quiet and privacy for thinking, painting, drinking tea, or playing music.

Galleries (lang) are narrow, covered walkways. They connect buildings and protect visitors from rain and sun. They also help divide the garden into different areas. These walkways are rarely straight. They zigzag or curve, following the garden wall, the pond's edge, or climbing a rock garden hill. They have small windows, sometimes round or in unusual shapes. These windows offer quick views of the garden as you pass through.

Windows and doors are important parts of Chinese garden architecture. Sometimes they are round (moon windows or a moon gate). They can also be oval, hexagonal, octagonal, or shaped like a vase or fruit. Some have very decorative ceramic frames. A window might perfectly frame a pine branch, a blooming plum tree, or another small garden scene.

Bridges are another common feature. Like the walkways, they are rarely straight. They zigzag (called Nine-turn bridges) or arch over ponds. This suggests bridges in rural China and provides good viewing spots. Bridges are often made from rough wood or stone slabs. Some gardens have brightly painted bridges, which give a cheerful feeling.

Gardens also often include small, simple houses for quiet time and thinking. Sometimes these look like rustic fishing huts. There are also isolated buildings used as libraries or studios (shufang).

-

Long gallery for viewing the lotus pond at the Prince Gong Mansion in Beijing

Artificial Mountains and Rock Gardens

The artificial mountain (jiashan) or rock garden is a key part of classical Chinese gardens. A mountain peak symbolized good qualities, strength, and lasting power in Confucian philosophy and the I Ching. A mountain peak on an island was also central to the legend of the Isles of the Immortals. Because of this, it became a main feature in many classical gardens.

The first rock garden appeared in Chinese garden history in Tu Yuan (meaning "Rabbit Garden"). It was built during the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE). During the Tang dynasty, rocks became art objects. They were judged by their shape (xing), material (zhi), color (se), and texture (wen). The poet Bo Juyi (772–846) wrote a list of famous rocks from Lake Tai. These rocks, made of limestone shaped by water, became the most valued for gardens.

During the Song dynasty, artificial mountains were mostly made of earth. But Emperor Huizong (1100–1125) almost ruined the Song Empire's economy. He destroyed bridges of the Grand Canal to carry huge rocks by boat to his imperial garden. During the Ming dynasty, building artificial mountains and caves from piles of rocks reached its peak. During the Qing dynasty, Ming rock gardens were seen as too artificial. New mountains were made from both rocks and earth.

Today, artificial mountains in Chinese gardens usually have a small viewing pavilion at the top. In smaller classical gardens, a single scholar rock represents a mountain. A row of rocks can represent a mountain range.

-

The Auspicious Cloud Capped Peak, a scholar stone in the Lingering Garden in Suzhou

Water in Chinese Gardens

A pond or lake is the main part of a Chinese garden. The main buildings are usually placed next to it. Pavilions surround the lake so you can see it from different angles. The garden often has a pond for lotus flowers, with a special pavilion to view them. There are usually goldfish in the pond, with pavilions over the water for watching them.

The lake or pond has an important symbolic meaning in the garden. In the I Ching, water means lightness and connection. It carries the food of life through valleys and plains. It also balances the mountain, the other main part of the garden. Water represents dreams and endless spaces. The shape of the pond often hides its edges from viewers. This makes it seem like the pond goes on forever. The softness of water contrasts with the hardness of rocks. Water reflects the sky, so it is always changing. Even a gentle wind can soften or remove the reflections.

Lakes and waterside pavilions in Chinese gardens were also inspired by a Chinese book. It was the Shishuo Xinyu by Liu Yiqing (403–444). He described Emperor Jianwen of Jin walking along the Hao and Pu Rivers. This was in the Garden of the Splendid Forest. Many gardens, especially in Jiangnan and northern China, have features and names from this book.

Small gardens have one lake, with a rock garden, plants, and buildings around it. Medium-sized gardens will have one lake with streams flowing into it. There will be bridges crossing the streams. Or, there might be one long lake divided into two by a narrow channel with a bridge. In a very large garden like the Humble Administrator's Garden, the main feature is the big lake with its symbolic islands. These islands represent the Isles of the Immortals. Streams flow into the lake, creating more scenes. Many buildings offer different views of the water. These include a stone boat, a covered bridge, and several pavilions by or over the water.

The streams in Chinese gardens always wind and curve. They are sometimes hidden by rocks or plants. A French Jesuit missionary, Father Attiret, worked as a painter for the Qianlong Emperor. He described a garden he saw:

"The canals are not like those in our country bordered with finely cut stone, but very rustic and lined with pieces or rock, some coming forward, some retreating. which are placed so artistically that you would think it was a work of nature."

-

Koi in the Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai

-

Pond and viewing pavilion in the Humble Administrator's Garden, in Suzhou

Flowers and Trees in Chinese Gardens

Flowers and trees are the fourth key part of a Chinese garden, along with water, rocks, and buildings. They show nature in its most lively form. They contrast with the straight lines of buildings and the hard, still rocks. They change with the seasons. They also provide sounds, like rain on banana leaves or wind in bamboo. And they offer pleasant smells to visitors.

Each flower and tree in the garden had its own special meaning. The pine, bamboo, and Chinese plum (Prunus mume) were called the "Three Friends of Winter" (歲寒三友). Scholars who built classical gardens valued them because they stayed green or bloomed in winter. Artists like Zhao Mengjian (1199–1264) often painted them together. For scholars, the pine meant long life and strength, and steady friendship. Bamboo, with its hollow stem, represented a wise person who was humble and sought knowledge. It was also known for bending in a storm without breaking. Plum trees were honored as a symbol of new life after winter and the start of spring. During the Song dynasty, the winter plum tree was a favorite. People loved its early pink and white blossoms and sweet smell.

The peach tree in Chinese gardens symbolized long life and never dying. Peaches were linked to the story The Orchard of Xi Wangmu, the Queen Mother of the West. This story said that in Xi Wangmu's magical orchard, peach trees flowered only after three thousand years. They didn't produce fruit for another three thousand years, and the fruit didn't ripen for another three thousand years. Those who ate these peaches became immortal. This legendary orchard was shown in many Chinese paintings and inspired many garden scenes. Pear trees were a symbol of fairness and wisdom. The word 'pear' sounded like 'quit' or 'separate'. So, cutting a pear was thought to bring bad luck, leading to the end of a friendship or romance. But a pear tree could also mean a long friendship or romance, since the tree lived a long time.

The apricot tree symbolized the path of the mandarin, or government official. During the Tang dynasty, those who passed the imperial examination were rewarded with a banquet in the garden of apricot trees, or Xingyuan.

The fruit of the pomegranate tree was given to young couples. It was hoped they would have many sons and descendants. The willow tree represented friendship and life's pleasures. Guests were given willow branches as a sign of friendship.

Of the flowers in Chinese gardens, the most loved were the orchid, peony, and lotus (Nelumbo nucifera). During the Tang dynasty, the peony was the most celebrated flower. It symbolized richness and had a delicate scent. The poet Zhou Dunyi wrote a famous poem about the lotus. He compared it to a junzi, a person with honesty and balance. The orchid was a symbol of nobility and impossible love. This is seen in the Chinese saying "a faraway orchid in a lonely valley." The lotus was admired for its purity. Its effort to grow out of the water to bloom in the air made it a symbol of seeking knowledge. The chrysanthemum was praised by the poet Tao Yuanming. He surrounded his simple hut with the flower and wrote a famous verse:

"At the feet of the Eastern fence, I pick a chrysanthemum, In the distance, detached and serene, I see the Mountains of the South."

The creators of Chinese gardens were careful to keep the landscape looking natural. Trimming and root pruning, if done, tried to keep the natural shape. Small, twisted, old-looking trees were especially valued in the miniature landscapes of Chinese gardens.

-

Plum blossoms (Prunus mume) in the Plum Garden, Jiangsu

-

Lotus blossom (Nelumbo nucifera)

Borrowed Scenery, Time, and Seasons

According to Ji Cheng's 16th-century book Yuanye, "The Craft of Gardens," "borrowed scenery" (jiejing) was the most important thing in a garden. This meant using scenes outside the garden. For example, a view of distant mountains or trees in a nearby garden. This created the illusion that the garden was much larger than it was. The most famous example was the misty view of the North Temple Pagoda in Suzhou. It was seen in the distance over the pond of the Humble Administrator's Garden.

But, as Ji Cheng wrote, it could also be "the perfect ribbon of a stream, animals, birds, fish, or other natural elements (rain, wind, snow)." Or it could be something less physical, like a moonbeam, a reflection in a lake, morning mist, or a red sunset sky. It could also be a sound. He suggested putting a pavilion near a temple so you could hear the chanted prayers. He also said to plant fragrant flowers next to paths and pavilions so visitors would enjoy their smells. Bird perches should be made to encourage birds to sing in the garden. Streams should be designed to make pleasant sounds. Banana trees should be planted in courtyards so rain would patter on their leaves. "A smart 'borrowing' doesn't need a reason," Ji Cheng wrote. "It simply comes from the feeling created by a beautiful scene."

The season and time of day were also important. Garden designers thought about which garden scenes would look best in winter, summer, spring, and autumn. They also considered which views were best at night, in the morning, or in the afternoon. Ji Cheng wrote: "In the middle of a busy city, you should choose calm and refined views. From a raised clearing, you look to the distant horizon, surrounded by mountains like a screen. In an open pavilion, a gentle breeze fills the room. From the front door, the running water of spring flows towards the marsh."

Actually, borrowing scenery is the final chapter of Yuanye. It explains borrowing scenery as a complete understanding of landscape design. The changing moods and looks of nature in a landscape are seen as an independent force. This force helps create the garden. It is nature, including the garden maker, that creates.

Concealment and Surprise

Another important garden element was hiding things and creating surprises. The garden was not meant to be seen all at once. It was designed to show a series of scenes. Visitors moved from one scene to another either through enclosed walkways or by winding paths. These paths hid the next scene until the last moment. Scenes would suddenly appear as you turned a path, looked through a window, or from behind a bamboo screen. They might be revealed through round "moon doors" or through windows of unusual shapes. Some windows had fancy patterns that broke the view into pieces.

Gardens in Art and Literature

Gardens play a big part in Chinese art and literature. At the same time, art and literature have inspired many gardens. The painting style called "Shanshui" (meaning 'mountains and water', or 'landscape'), started in the 5th century. It set the rules for Chinese landscape painting. These rules were very similar to those for Chinese gardening. These paintings were not meant to be super realistic. They were meant to show what the artist felt, rather than just what they saw.

The landscape painter Shitao (1641–1720) wrote that he wanted to "'...create a landscape which was not spoiled by any commonness..." He wanted to make viewers feel a sense of wonder. He aimed "to express a universe unreachable by humans, with no path leading there. Like the islands of Bohai, Penglan, and Fanghu, where only immortals can live, and which a human cannot imagine. That is the wonder that exists in the natural universe. To show it in painting, you must show jagged peaks, cliffs, hanging bridges, great chasms. For the effect to be truly amazing, it must be done purely by the power of the brush." This was the feeling garden designers wanted to create with their scholar rocks and miniature mountain ranges.

In his book, Craft of Gardens, the garden designer Ji Cheng wrote: "The spirit and charm of mountains and forests must be studied deeply. Only knowing the real allows for creating something artificial. This way, the created work has the spirit of the real. This is partly due to divine inspiration, but mostly due to human effort." He described the effect he wanted for an autumn garden scene: "The feelings are in harmony with purity, with a sense of quiet retreat. The spirit enjoys the mountains and valleys. Suddenly, the spirit, free from small worldly things, becomes lively. It seems to enter a painting and walk around in it..."

In literature, gardens were often the subject of "Tianyuan" poetry. This means 'fields and gardens'. It was most popular in the Tang dynasty (618–907) with poets like Wang Wei (701–761). The names of the Surging Waves Garden and the Garden of Meditation in Suzhou come from lines of Chinese poetry. Inside the gardens, individual pavilions and viewing spots often had verses of poems. These were written on stones or plaques. The Moon Comes with the Breeze Pavilion at the Couple's Retreat Garden, used for moon-viewing, has a verse by Han Yu:

- "The twilight brings the Autumn

- And the wind brings the moon here."

And the Peony Hall in the Couple's Retreat Garden is dedicated to a verse by Li Bai:

- "The spring breeze is gently stroking the balustrade

- and the peony is wet with dew."

Wang Wei (701–761) was a poet, painter, and Buddhist monk. He first worked as a court official. Then he retired to Lantian. There, he built one of the first wenren yuan, or scholar's gardens. It was called the Valley of the Jante. In this garden, twenty scenes unfolded before the viewer, like paintings in a scroll. Each scene was shown with a poem. For example, one scene illustrated this poem:

- "The white rock emerges from the torrent;

- The cold sky with red leaves scattering:

- On the mountain path, the rain is fleeing,

- the blue of the emptiness dampens our clothes."

The Valley of the Jante garden is gone now. But its memory, kept in paintings and poems, inspired many other scholar's gardens.

The importance of gardens in society and culture is shown in the famous novel Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin. The story takes place almost entirely in a garden.

Philosophy Behind the Gardens

Chinese classical gardens had many uses. They could be used for parties, celebrations, meetings, or romance. They could also be used for quiet time and thinking. They were calm places for painting, poetry, calligraphy, and music. They were also for studying old books and drinking tea. A garden was a way to show the owner's good taste. But it also carried a deeper philosophical message.

Taoism greatly influenced classical gardens. After the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), gardens were often built as retreats. Government officials who had lost their jobs or wanted to escape the pressures of court life built them. They chose to follow Taoist ideas of stepping away from worldly worries.

For Taoists, true understanding could be reached by thinking about the unity of all creation. In this view, order and harmony are natural parts of the world.

The gardens were meant to make you feel like you were wandering through a natural landscape. They aimed to make you feel closer to an ancient way of life. They also helped you appreciate the harmony between humans and nature.

In Taoism, rocks and water were opposites, yin and yang. But they also completed each other. Rocks were solid, but water could wear them away. The deeply eroded rocks from Lake Tai used in classical gardens showed this idea.

"Borrowing scenery" is a very basic idea in Ming period garden design (as discussed above).

The winding paths and zig-zag bridges that led visitors from one garden scene to another also had a message. They showed a Chinese saying: "By detours, access to secrets."

According to landscape historian Che Bing Chiu, every garden was "a search for paradise, for a lost world, for a perfect universe." The scholar's garden was part of this search. On one hand, it was a search for the home of the Immortals. On the other hand, it was a search for the "golden age" that scholars loved.

A more recent idea about garden philosophy came from Zhou Ganzhi in 2007. He was the President of the Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture. He said: "Chinese classical gardens are a perfect mix of nature and human work. They copy nature and show its beauty fully. They can also be seen as an improvement on nature. From them, the light of human artistic genius shines."

Influence of Chinese Gardens

Chinese Influence on Japanese Gardens

Chinese classical gardens had a big impact on early Japanese gardens. China's influence first reached Japan through Korea before 600 AD. In 607 AD, the Japanese crown prince Shotoku sent a diplomatic group to the Chinese court. This started a cultural exchange that lasted for centuries. Hundreds of Japanese scholars went to China to study the language, political system, and culture. The Japanese Ambassador to China, Ono no Imoko, described the great landscape gardens of the Chinese Emperor to the Japanese court. His reports greatly influenced how Japanese landscapes were designed.

During the Nara period (710-794), when the Japanese capital was at Nara, and later at Heian, the Japanese court built large landscape gardens. These had lakes and pavilions, like the Chinese style. Nobles used them for walking and leisurely boat rides. More private gardens were built for quiet thinking and religious meditation.

A Japanese monk named Eisai (1141–1215) brought the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism from China to Japan. This led to a famous and unique Japanese gardening style, the Zen garden. The garden of Ryōan-ji is a good example. He also brought green tea from China to Japan. It was first used to keep monks awake during long meditation. This became the basis for the Japanese tea ceremony, an important ritual in Japanese gardens.

The Japanese garden designer Muso Soseki (1275–1351) created the famous Moss Garden (Kokedera) in Kyoto. It included a copy of the Isles of Eight Immortals, called Horai in Japanese. These islands were an important feature of many Chinese gardens. During the Kamakura period (1185–1333), and especially during the Muromachi period (1336–1573), Japanese gardens became simpler than Chinese gardens. They started following their own artistic rules.

Chinese Influence in Europe

The first European to describe a Chinese garden was the Venetian merchant and traveler Marco Polo. He visited the summer palace of Kublai Khan at Xanadu. Kublai Khan's garden later influenced European culture. In 1797, it inspired the romantic poem, Kubla Khan, by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Marco Polo also described the gardens of the imperial palace in Khanbaliq. This was the Mongol name for the city that became Beijing. He described walls, railings, and pavilions around a deep lake full of fish, swans, and other water birds. The main feature was a man-made hill, one hundred steps high and a thousand steps around. It was covered with evergreen trees and decorated with green azurite stones.

The first Jesuit priest, Francis Xavier, arrived in China in 1552. The priest Matteo Ricci was allowed to live in Beijing in 1601. Jesuit priests began sending stories about Chinese culture and gardens to Europe. Louis Le Comte, a French mathematician, traveled to China in 1685. He described how Chinese gardens had caves, artificial hills, and rocks piled to look like nature. He noted that they did not arrange their gardens in straight, geometric ways.

In the 18th century, Chinese vases and other decorative items arrived in Europe. This led to a rise in popularity for Chinoiserie, a European art style that copied Chinese designs. Painters Watteau and François Boucher painted Chinese scenes as they imagined them. Catherine the Great decorated a room in her palace in Chinese style. There was great interest in everything Chinese, including gardens.

In 1738, the French Jesuit missionary and painter Jean Denis Attiret went to China. He became court painter to the Qianlong Emperor. He described in great detail what he saw in the imperial gardens near Beijing:

"One comes out of a valley, not by a straight wide alley as in Europe, but by zigzags, by roundabout paths. Each one is decorated with small pavilions and caves. When you leave one valley, you find yourself in another. It's different from the first in its landscape or building style. All the mountains and hills are covered with flowering trees, which are common here. It is a true paradise on Earth. The canals are not like ours – bordered with cut stone. They are rustic, with pieces of rock, some leaning forward, some backward. They are placed so artfully you would think they were natural. Sometimes a canal is wide, sometimes narrow. Here they twist, there they curve, as if hills and rocks really created them. The edges are planted with flowers in rock gardens, which seem natural. Each season has its own flowers. Besides the canals, everywhere there are paths paved with small stones. These paths lead from one valley to another. These paths also twist and turn, sometimes close to the canals, sometimes far away."

Attiret wrote:

- "Everything is truly great and beautiful, both in design and execution. And [the gardens] impressed me more because I had never seen anything like them anywhere else in the world."

The Qianlong Emperor (1711–1799) was also interested in what was happening in Europe. He asked the Jesuit priest Father Castiglione, who was trained in engineering, to build fountains for his garden. These were similar to those he had heard about in the gardens at Versailles.

Chinese architecture and beauty ideas may have also influenced the English landscape garden style. In 1685, the English diplomat Sir William Temple wrote an essay. In it, he compared European symmetrical gardens with asymmetrical Chinese designs. Temple had never visited China. But he had heard of Chinese (or Japanese) gardens, perhaps in the Netherlands. He noted that Chinese gardens avoided straight rows of trees and flower beds. Instead, they placed trees, plants, and other garden features in irregular ways. This was to catch the eye and create beautiful scenes. He called this approach Sharawadgi. His ideas about Chinese gardens were mentioned by Joseph Addison in an essay in 1712. Addison used them to criticize English gardeners who copied French styles, making their gardens unnatural.

The English landscape garden style was already popular in England in the early 1700s. It was influenced by British upper classes traveling to Italy. They wanted a new garden style to match their Palladian country houses. It was also influenced by the romantic landscapes of painters like Claude Lorraine. But the new and exotic Chinese art and architecture in Europe led to something new. In 1738, the first Chinese house was built in an English garden, at Stowe House. It stood alongside Roman temples and Gothic ruins.

The style became even more popular thanks to William Chambers (1723–1796). He lived in China from 1745 to 1747. He wrote a book, The Drawings, buildings, furniture, habits, machines and untensils of the Chinese, published in 1757. He encouraged Western garden designers to use Chinese ideas. These included hiding things, avoiding perfect symmetry, and making things look natural. Later, in 1772, Chambers published his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening. This was a rather imaginative description of ideas about naturalistic gardening in China.

Chambers strongly criticized Capability Brown, a leading designer of English landscape gardens. Chambers thought Brown's designs were boring. Chambers believed gardens should be full of surprises. In 1761, he built the Great Pagoda in Kew Gardens, London. He also built a mosque, a temple of the sun, a ruined arch, and a Palladian bridge there. Thanks to Chambers, Chinese buildings started appearing in other English gardens. Then they appeared in France and other parts of Europe. Carmontelle added a Chinese pavilion to his garden at Parc Monceau in Paris (1772). The Duc de Choiseul built a pagoda on his estate at Chanteloup between 1775 and 1778. This is now the only part of that estate that remains. The Russian Empress Catherine the Great built her own pagoda in the garden of her palace of Tsarskoye Selo, near Saint Petersburg, between 1778 and 1786. Many French critics disliked the term "English Garden." So they started using the term 'Anglo-Chinois' to describe the style. By the late 1800s, parks all over Europe had pretty Chinese pagodas, pavilions, or bridges. But few gardens truly showed the deeper and more subtle beauty of real Chinese gardens.

|

See also

In Spanish: Jardín chino para niños

In Spanish: Jardín chino para niños

- Classical Gardens of Suzhou

- Chengde Mountain Resort

- Ji Cheng

- Moon gate

- Moon Bridge

- List of Chinese gardens

- List of botanical gardens in China

- Pear Garden

- Penjing

- Gongshi

- West Lake

- Borrowed scenery

- Chinese architecture