Wanli Emperor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wanli Emperor |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

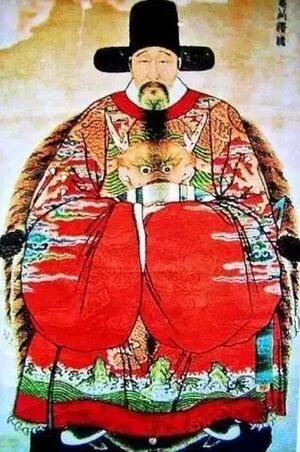

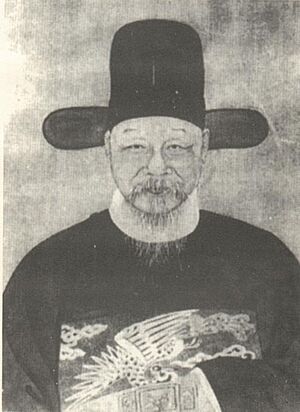

Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, kept in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 19 July 1572 – 18 August 1620 | ||||||||||||||||

| Enthronement | 19 July 1572 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Longqing Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Taichang Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Regents |

See list

|

||||||||||||||||

| Born | 4 September 1563 Jiajing 42, 17th day of the 8th month (嘉靖四十二年八月十七日) Shuntian Prefecture, North Zhili |

||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 August 1620 (aged 56) Wanli 48, 21st day of the 7th month (萬曆四十八年七月二十一日) Hongde Hall, Forbidden City |

||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Dingling Mausoleum, Ming tombs, Beijing | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts |

Empress Xiaoduanxian

(m. 1578; died 1620)Empress Dowager Xiaojing

(m. 1578; died 1611)Grand Empress Dowager Xiaoning

(m. 1581) |

||||||||||||||||

| Issue Detail |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| House | Zhu | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ming | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Longqing Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Dowager Xiaoding | ||||||||||||||||

| Wanli Emperor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 萬曆帝 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 万历帝 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "Ten Thousand Calendars" Emperor | ||||||

|

|||||||

The Wanli Emperor (born Zhu Yijun on September 4, 1563 – died August 18, 1620) was the 13th emperor of China's Ming dynasty. He ruled for 48 years, from 1572 to 1620, which was the longest reign of any Ming emperor. His era name, "Wanli," means "ten thousand calendars."

He became emperor when he was only nine years old. For the first ten years, a skilled advisor named Zhang Juzheng helped him lead the country. With support from the emperor's mother, Lady Li, and powerful eunuchs, China became strong economically and militarily. The emperor respected Zhang Juzheng greatly. However, after Zhang died in 1582, the emperor took full control and changed many of Zhang's policies.

The Wanli era saw a big boost in industries like silk, cotton, and porcelain. Farming also grew, and trade within China and with other countries increased. Cities like Suzhou and Nanjing became very rich. But even with this growth, the government's money was often low. Rich merchants lived in luxury, while most farmers and workers remained poor.

Towards the end of his reign, the emperor became frustrated with constant arguments among his officials. He tried to make his third son, Zhu Changxun, the crown prince. But officials strongly disagreed, leading to a long conflict. In 1601, he finally named his eldest son, Zhu Changluo, as the crown prince. In his last years, a group called the Jurchens grew powerful in the northeast. They defeated Ming armies in 1619, taking over some land.

Contents

- Becoming Emperor: Childhood and Early Rule

- Wanli as Emperor: Key Events and Challenges

- Economy and Society: Changes in the Ming Dynasty

- Culture and Society: Arts and Learning

- Military and Foreign Policy: Protecting the Empire

- End of Reign: Death and Successors

- Understanding the Wanli Emperor's Reign

- Family Life

- The Emperor's Tomb

- See also

Becoming Emperor: Childhood and Early Rule

Zhu Yijun was born on September 4, 1563. His father, Zhu Zaiji, became the Longqing Emperor in 1567. Sadly, his father died five years later, on July 5, 1572. Zhu Yijun then became emperor two weeks later, on July 19, 1572. Before his death, the Longqing Emperor asked his minister, Zhang Juzheng, to guide the young emperor.

Young Zhu Yijun was very energetic and a quick learner. He was intelligent and always knew what was happening in the empire. Zhang Juzheng hired eight teachers to teach him about Confucianism, history, and calligraphy. History lessons focused on showing him examples of good and bad rulers. Zhang even wrote a special collection of historical stories for him.

However, Zhang worried that the emperor's love for calligraphy would distract him from his duties. So, he stopped the calligraphy lessons. The emperor's mother and officials also worried he might become like the Zhengde Emperor, who loved traveling and military activities. They encouraged him to stay in the Forbidden City. After 1588, he stopped leaving Beijing and stopped attending public ceremonies after 1591.

In his early rule, the Wanli Emperor cared about his people. He fought against corruption and worked to improve border defenses. His mother, a Buddhist, influenced him to be lenient with punishments. But he could also be tough on officials who offended him. He was known to be both vulnerable and generous. However, his health began to decline in the mid-1580s.

Zhang Juzheng and the emperor's mother taught him to be modest. But the emperor felt humiliated when he learned Zhang Juzheng lived in luxury. This made him distrust officials. Two years after Zhang's death, his family was punished, and their property was taken.

Wanli as Emperor: Key Events and Challenges

Zhang Juzheng's Influence (1572–1582)

When the Wanli Emperor became ruler, Zhang Juzheng became the most powerful official. He stayed in power for ten years until his death in 1582. Zhang wanted to make China "rich and strong." He worked to centralize the government and increase the emperor's power. He had the support of the emperor's mother and powerful eunuchs.

Zhang made many changes, like allowing people to pay taxes in silver instead of goods. This was called the Single Whip Reform. He also updated land records and reduced unnecessary government activities. These changes made the government more efficient and helped save money. By 1582, the government had large reserves of grain and silver.

Zhang also wanted peace with the Mongols. He focused on strengthening border defenses and building peaceful relationships through trade. He appointed skilled military leaders, which was unusual at the time.

Some officials criticized Zhang for being too powerful. When his father died, Zhang was supposed to leave office for mourning, but the emperor kept him. This caused a lot of anger. Zhang punished his critics, which further damaged his reputation. After Zhang Juzheng died, he was accused of corruption. His supporters were removed from office, and his family's wealth was taken.

Challenges from Officials (1582–1596)

After Zhang's death, no single strong leader emerged in the government. The emperor and officials were wary of concentrating too much power. From 1582 to 1591, Shen Shixing led the Grand Secretariat. He tried to find common ground between the emperor and the officials, but it was difficult.

Officials who had opposed Zhang Juzheng now criticized higher-ranking officials. This angered the emperor, especially since these critics didn't offer solutions. By 1585, officials even started criticizing the emperor's personal life. The emperor became frustrated and stopped meeting with officials regularly. He communicated mostly through written reports.

He also left many government positions empty, which was against the rules. This was his way of showing his distrust of the regular administration. However, the government still managed to function. Taxes were collected, rebellions were stopped, and aid was given to people affected by famine.

Hundreds of reports came to the emperor's desk daily. He only read and decided on a few. The rest were handled by eunuchs, who usually followed the Grand Secretaries' advice. But sometimes, they made different decisions if they thought the emperor would disagree.

Succession Debates (1586–1614)

In 1586, the question of who would be the next emperor became a big issue. The emperor favored his third son, Zhu Changxun, whose mother was his favorite concubine, Lady Zheng. This was against the tradition of choosing the eldest son, Zhu Changluo. This caused a major disagreement among government officials.

Officials strongly supported Zhu Changluo's right to be the crown prince. The emperor delayed his decision, saying he was waiting for a son from the empress. In 1589, he agreed to name Zhu Changluo as his successor, but Lady Zheng opposed it. This led to more arguments and even arrests when a pamphlet criticizing Lady Zheng spread in Beijing.

The empress and the emperor's mother also supported Zhu Changluo. Finally, in 1601, after many protests, the Wanli Emperor named Zhu Changluo as the crown prince. Zhu Changxun was given the title of Prince of Fu, but he stayed in Beijing, which kept rumors alive that the succession was still uncertain. It wasn't until 1614 that the emperor finally sent Prince Fu to his assigned province.

Mines and Taxes (1596–1606)

In 1596, the emperor decided to open new silver mines to help the government's finances. He sent eunuchs and Imperial Guard officers to manage these mines. Officials opposed this, believing the state shouldn't compete with people for profit. They also disliked that eunuchs, a rival group, were in charge.

When the war in Korea restarted in 1597, the emperor needed more money. He gave eunuchs more power to collect mining and trade taxes. These eunuch commissioners could even supervise local officials. The emperor quickly responded to their reports, showing his trust in them over traditional officials. This made many Confucian scholars see him as greedy.

However, by 1605, the emperor realized that the eunuchs were also corrupt and that the mining tax was causing more problems than it solved. In 1606, he stopped the state mining operations and returned tax collection to the usual authorities.

Official Evaluations and Disputes

In the Ming government, the emperor had the final say. But if the emperor wasn't strong, power was shared among different groups. During Wanli's reign, officials often debated important decisions, including who should be appointed to high positions. This meant that public opinion became very important.

The emperor tried to appoint officials without these debates, but it often led to protests. For example, in 1591, he tried to appoint a Senior Grand Secretary without consulting others. Officials criticized this, saying it was unfair. The emperor sometimes gave in, but he still occasionally made appointments without collective debate, causing more protests.

Officials' careers also depended on their reputation, which was judged by their colleagues through surveys. This made public opinion even more powerful. Groups of officials fought to control public opinion, while the emperor's influence decreased.

Donglin Movement and Factions (1606–1620)

In 1604, Gu Xiancheng started the Donglin Academy in Wuxi. It became a major center for discussions among intellectuals. The Donglin movement believed in strict Confucian morality. They thought that officials should live exemplary lives and that private and public morality were connected. They criticized the emperor for not naming his eldest son as successor, seeing it as unethical.

The Donglin movement wanted a government based on Confucian values. They believed educated local gentry should lead the people. They also wanted the Censorate (officials who criticized others) to be independent and limit the power of eunuchs. However, their focus on morality over practical governance sometimes made it harder to run the large empire effectively.

Factional disputes became common, with officials using evaluations to remove opponents. For example, in 1593, the Donglins used their positions to remove supporters of the Grand Secretaries. The emperor sometimes intervened in these disputes, which led to more protests about his "interference."

In the last decade of Wanli's reign, the government was often paralyzed by these conflicts. The emperor left many high positions empty and ignored critical reports.

Economy and Society: Changes in the Ming Dynasty

New Crops from America

In the 16th century, Europeans brought new crops to China, like maize (corn), sweet potatoes, and peanuts. During the Wanli era, tobacco and sweet potatoes became popular.

Tobacco was grown in Fujian and exported to the Philippines. It became popular among the poor and then among the rich. By the early Qing period, many people, including officials and soldiers, smoked.

Sweet potatoes arrived in the early 1590s. After a famine in Fujian in 1594, the local governor encouraged growing them. They quickly spread in Fujian and Guangdong and later to other parts of China.

Economic Growth and Trade

The Wanli era saw a big boom in industries like silk, cotton, and porcelain. Large ironworks with thousands of workers appeared in Guangdong. Farming became more specialized, and trade between different regions of China grew a lot. Cities in Jiangnan, like Suzhou and Nanjing, became very wealthy. Suzhou was famous for silk, and Songjiang for cotton.

Much of China's production was exported in exchange for silver. Between 1560 and 1640, huge amounts of silver came into China from Spanish colonies in the Americas and from Japan. This silver helped the economy grow, especially in cotton and silk industries. However, this growth didn't benefit everyone. Land and rice prices stayed the same or even fell, and wages in the cotton industry declined. While rich city dwellers lived in luxury, most farmers and workers remained poor.

The Ming government also started buying goods from private merchants instead of relying on state-owned factories. This helped private businesses grow. The "Single Whip Reform" converted many taxes and services into silver payments, which helped streamline tax collection.

In 1581, Zhang Juzheng ordered a new land survey to improve tax collection. Fields were measured, and owners were recorded. This survey helped future governments. The government's silver income from taxes doubled in the 1570s. However, the influx of silver also caused some inflation in wealthy coastal regions.

Money and Coins

Many officials worried that silver would completely replace bronze coins. They also feared relying too much on silver from other countries. In the 1570s and 1580s, there were debates about silver shortages causing prices to fall.

The import of silver made it less valuable compared to gold and copper in China, but it was still worth more than in other parts of the world. The government's silver income increased significantly. However, this also led to gold and coins being exported.

The government tried to bring back the use of coins. Mints were opened in Beijing, Nanjing, and other provinces. But there were problems like copper shortages and difficulty finding skilled workers. Many people preferred using silver, especially in the south. Private, illegal coins also became common. By 1579, Zhang Juzheng admitted that the attempt to reintroduce coins had largely failed.

In 1599, the Wanli Emperor tried again to increase coin production, mainly in Nanjing. But the coins mostly stayed around Nanjing, causing their value to drop. In 1606, floods disrupted metal imports, raising copper prices. The government cut coin production, leading to laid-off workers making illegal coins. This caused problems for workers who were paid in coins, as merchants sometimes refused to accept them.

Culture and Society: Arts and Learning

Literature and Drama

The Wanli era saw a boom in printed literature. Books became more affordable and widely available. Europeans visiting China were amazed by the number of books. Literacy was widespread, even among poorer families.

The book market grew rapidly. Publishers printed not only official histories but also many types of fiction, encyclopedias, and how-to guides. Fiction became very popular. Two famous novels from this time are Journey to the West and Jin Ping Mei.

Private libraries also grew. Some scholars had tens of thousands of books. These large libraries were often housed in separate buildings. Private newspapers also started, initially reprinting official news, but later producing their own stories.

Drama also developed significantly. The Kunqu style of music became very popular in plays. Wealthy families often had their own theater groups. Tang Xianzu was a famous playwright, known for his "four dream plays," especially The Peony Pavilion.

Imperial Examinations and Social Change

To protect their wealth, merchant families often encouraged their sons to study for the civil service examinations and become officials. In the Wanli era, merchants were finally allowed to take these exams. However, it was still very difficult for them to pass the highest level. Many merchants found ways around the rules, like registering under different names. By the late Ming period, many successful exam candidates came from merchant families.

The "eight-legged essay" was a very important writing style for exams. Mastering it was key to success. This style became popular during the Wanli era. Studying for these exams was expensive, and many students went into debt. Official salaries were not high, so officials often relied on other income, which was sometimes seen as corrupt.

In 1583, the government tightened control over provincial exams. Chief examiners were chosen from the Hanlin Academy, a prestigious group of scholars.

Fashion and Social Status

In earlier Ming times, the government controlled clothing styles. But by the 1560s, these rules were no longer enforced, and fashion trends changed constantly. Suzhou became the center of fashion.

Wealthy merchants, who had become rich from the influx of silver, often displayed their wealth in flashy ways. Traditional elites looked down on this, calling it "vulgar." They tried to maintain their higher social status through fashion and by setting standards for taste. By the 1590s, writers from the gentry class even published guides on what antiques and objects were proper to own. However, fake antiques also became common.

Military and Foreign Policy: Protecting the Empire

Strengthening the Military

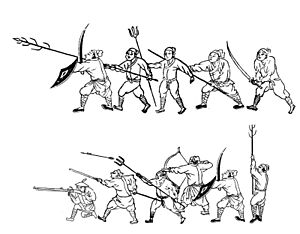

The Wanli era saw three major military campaigns: stopping a rebellion in Ningxia, fighting Japan in Korea, and putting down a rebellion in Bozhou. These campaigns involved moving tens of thousands of soldiers and supplying them over long distances. The Ming dynasty's success showed its increased military power from the 1570s to the early 1600s.

The Wanli Emperor, like his teacher Zhang Juzheng, cared a lot about military matters. He trusted generals more than civil officials and gave them special powers to make quick decisions. He also spent a lot of his own money to equip the troops.

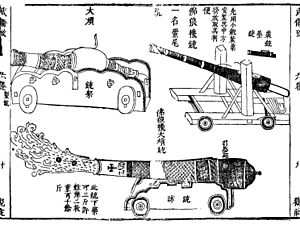

On the northern border, the emperor wanted to use more aggressive tactics instead of just defending. He believed in building strength to protect the borders. Under skilled generals, the Ming army was very strong. By the early 1600s, China had over 4 million men in its army. The government started hiring mercenaries, who were better trained and more effective than traditional hereditary soldiers. They also used "wolf troops" from minority groups. Many military manuals were written to support these developments.

Even after a major defeat in 1619, the emperor protected his generals from being punished by the government.

The Ningxia Rebellion (1592)

In March 1592, a rebellion broke out in Ningxia, an important fortress city in the northwest. Chinese soldiers and a Mongol leader named Pubei joined forces. They took control of Ningxia and many nearby forts. The rebels were experienced soldiers.

The emperor quickly ordered troops to be mobilized. Wei Xueceng, an experienced military official, was put in charge. He secured the Yellow River bank and recaptured many forts, leaving only Ningxia city under rebel control. But Wei Xueceng wanted to negotiate, worrying about civilian lives. The emperor, however, decided to crush the rebellion quickly.

The Ming troops besieged Ningxia. In July, General Li Rusong was appointed to lead the suppression, which was unusual because a professional officer, not a civilian official, was given overall command. Li Rusong attacked the city day and night. The emperor approved a plan to build a dam around the city and flood it. By September, the city was flooded with three meters of water. The rebels ran out of food. The city fell in mid-October, and the rebel leaders were captured and executed. After this victory, many of these troops were sent to Korea.

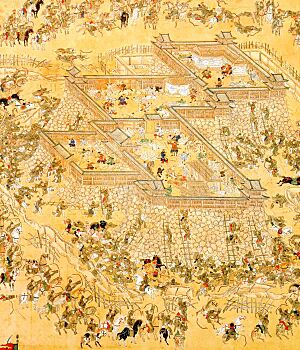

The Imjin War: Korea and Japan (1592–1598)

In the early 1590s, Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi wanted to conquer East Asia, starting with Korea and then China. In May 1592, Japanese troops landed in Korea and quickly took Seoul. The Korean king asked China for help. The Wanli Emperor decided to fight Japan.

Initially, a small Ming scouting force was defeated. This shocked the Beijing court, and they began preparing coastal defenses. A large Ming army gathered in Liaodong, the region bordering Korea. Korean Admiral Yi Sun-sin led the Korean navy to important victories, helping organize resistance.

After the Ningxia rebellion was defeated, more Ming troops, led by Li Rusong, joined the fight in Korea. By May 1593, the Chinese and Korean forces pushed the Japanese back to southeastern Korea. A truce was negotiated, but talks failed in 1596, and Hideyoshi attacked again.

The second Japanese invasion in 1597 was also unsuccessful. Ming troops arrived and pushed the Japanese back. The Korean navy, again led by Yi Sun-sin, gained control of the sea. After Hideyoshi died in September 1598, the remaining Japanese troops left Korea.

The Imjin War was one of the biggest conflicts of the 16th century. Japan sent over 150,000 soldiers, and China sent over 40,000, later doubling that number. China spent about 17 million liang of silver on the war. Korea suffered devastating losses.

Yang Yinglong's Rebellion (1599–1600)

The Yang family had controlled a mountainous region near the borders of Huguang, Guizhou, and Sichuan for centuries. Yang Yinglong, the leader, was ambitious and saw the Ming troops as weak. He started attacking local tribes and Chinese settlers.

The government in Beijing initially ignored these problems. But in 1590, open fighting broke out between Yang Yinglong's warriors and Ming forces. Yang Yinglong surrendered but was sentenced to execution. He offered a large payment and 5,000 troops for the war in Korea to gain his release. After being released, he plundered many areas and even declared himself emperor. His 100,000 Miao soldiers caused fear in the region.

Focused on the war in Korea, the Wanli Emperor delayed dealing with this rebellion until 1599. He appointed skilled officials and generals, including Liu Ting, to suppress it. The rebels attacked major cities like Chongqing and Chengdu. By early 1600, the Ming army had 240,000 soldiers. Yang Yinglong gathered about 150,000 warriors, but the Ming troops had better weapons like cannons and rifles.

The Ming army attacked from eight directions in March 1600. They systematically pushed back the rebels and surrounded Yang Yinglong in his mountain fortress of Hailongtun. The fortress fell in mid-July, and Yang Yinglong was killed. Over 22,000 rebels died in the fighting. After the rebellion, Yang Yinglong's territory was brought under the standard Chinese administration.

Other Conflicts and Border Wars

During the Wanli Emperor's reign, there were also other uprisings, like those by the White Lotus sect in Shandong in 1587 and 1616.

Despite a peace agreement with the Mongols in 1571, there were still occasional clashes on the northern border. Ming troops raided Mongolia and Manchuria, burning settlements and taking livestock. In 1591, General Li Chengliang destroyed a Mongol camp, killing 280 Mongols.

Conflicts also happened on the southwestern border with the Burmese. Ming armies successfully pushed back the Burmese and even entered Burma. In 1600, combined Ming and Siamese forces burned the Burmese capital of Pegu. The Vietnamese also raided borderlands in 1607.

Relations with Spain, Portugal, and Japan

In the early 1570s, the Spanish settled in the Philippines. Trade with the Spanish was very profitable for the Chinese, who sold silk for double its price in China. The Spanish paid in American silver, which came to China in large amounts. This trade led to a rapid growth of a Chinese community in Manila. However, the Spanish often distrusted the Chinese, leading to conflicts. In 1603, a violent event occurred where thousands of Chinese people were killed.

Portuguese traders also brought American silver to China. They settled in Macau in the 1550s and were allowed to trade in Canton. The Dutch also became major traders, buying Chinese porcelain.

Jesuit missionaries like Matteo Ricci came to China from Europe. They were successful in spreading Christianity by respecting Chinese culture. They gained the trust of Chinese officials and were valued for their knowledge in mathematics and astronomy. Ricci was even accepted by the emperor.

China's silver was scarce, making it more valuable than in other countries. This made Chinese goods, like silk, popular worldwide. Chinese silk was even exported to Latin American countries like Peru and Mexico.

Japan also increased its silver exports to China after discovering new mines. Japanese silver imports were often handled by the Portuguese due to China's ban on direct trade with Japan. By the early 17th century, Japanese silver exports continued to rise, leading to more imports of luxury goods like silk into Japan.

First Contact with Russia (1618)

In the autumn of 1618, the first Russian ambassadors arrived in Beijing. Led by Ivan Petlin, a group of Siberian Cossacks traveled from Tomsk, through Mongolia, to Beijing. However, because they didn't bring gifts or official papers, Ming officials didn't allow them to meet the emperor.

Still, they were welcomed by the Ministry of Rites and received a letter from the Wanli Emperor. The letter agreed to future Russian missions and trade. The Russians returned home, but due to Russia's focus on Europe, there were no more official contacts with China until the Ming dynasty ended.

Rise of the Jurchens (Northeast)

In 1583, Nurhaci, a leader of a Jurchen tribe in southern Manchuria, began building his own state. He united the Jurchens with support from the Ming dynasty. However, some Ming officials worried about his growing power. Nurhaci showed respect to the Ming dynasty by visiting Beijing in 1590 and 1597. By the early 1590s, his state had a large military force. In 1599, he introduced a new Manchu script, and in 1601, a new military organization based on banners.

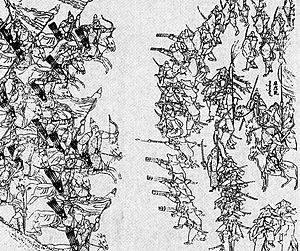

In 1618, Nurhaci controlled almost all Jurchen tribes. He attacked Fushun, a Ming city, which started a war with China. The Ming responded with a large expedition in April 1619. The Ming army had about 100,000 men, including Chinese, Korean, and Jurchen allies. Nurhaci, with 50,000–60,000 soldiers, used his knowledge of the land and weather to defeat the Ming armies one by one. Two Ming generals, Du Song and Liu Ting, died in battle. Nurhaci then captured more Ming territory.

End of Reign: Death and Successors

In his final months, the Wanli Emperor's health worsened. He died on August 18, 1620. After his death, money was immediately sent from his treasury to the border troops to strengthen defenses. Mining and trade taxes collected by eunuchs were also stopped.

On August 28, 1620, the Wanli Emperor's eldest son, Zhu Changluo, became the Taichang Emperor. He relied on officials from the Donglin movement. However, he fell ill and died just one month later, on September 26, 1620.

His fifteen-year-old son, Zhu Youjiao, became the new emperor, known as the Tianqi Emperor. Tianqi enjoyed woodworking and making models, but not his official duties. During his reign, there was a power struggle between officials and eunuchs. A powerful eunuch named Wei Zhongxian dominated the court from 1624.

In 1627, after Tianqi Emperor's death, his younger brother Zhu Youjian became the Chongzhen Emperor. He removed Wei Zhongxian's group. However, he struggled to control the fighting among officials and build a strong government.

While the government fought internally, conditions in the countryside got worse in the 1620s. From 1628, northern China faced peasant rebellions and war. Starving people fled to cities, and entire areas were destroyed. In 1644, the rebel army captured Beijing, and the Chongzhen Emperor took his own life. General Wu Sangui, who commanded the Ming border army, joined forces with the Qing dynasty (the Jurchen state founded by Nurhaci). The Qing army quickly defeated the rebels and took control of China. In 1662, the last Ming emperor was captured and executed.

Understanding the Wanli Emperor's Reign

Historians have different views on the Wanli Emperor. Traditional Chinese historians often blame him for the decline of the Ming dynasty. They describe him as lazy, selfish, and reckless, focusing on his personal life and his use of eunuchs. This view comes from Confucian scholars who disagreed with his choices, especially his protection of military officers over civilian officials. Modern historians, including some in the West, have often followed this traditional view.

However, some argue that this portrayal is unfair. They believe the emperor's actions were misunderstood or that he was trying to solve real problems. The Ming political system relied heavily on moral principles. When Zhang Juzheng tried to rule effectively through personal connections, his opponents criticized his personal life instead of his policies. After Zhang's death, the government became divided, and important reforms were ignored.

The Wanli Emperor, like Zhang Juzheng, wanted to strengthen the military, control the bureaucracy, and reduce factionalism. He spent a lot of money on the army and protected his generals. During his reign, Ming armies successfully defended borders, fought in Burma, stopped a major rebellion in Ningxia, fought in Korea, and put down a large rebellion in Sichuan. Later Confucian scholars often focused only on the defeat at Sarhu, ignoring the many victories achieved earlier.

Family Life

The Wanli Emperor had 18 children with eight different women. Eight of his children were sons, and five of them lived to adulthood. He also had two daughters who survived. The most important women in his life were his mother, Empress Dowager Li, and his favorite concubine, Lady Zheng.

After the Longqing Emperor died, Wanli's mother became Empress Dowager. She helped lead the government while her son was young, working with Zhang Juzheng and later other powerful officials. She was a strong supporter of her son's eldest son, the future Taichang Emperor, becoming the next ruler, even though Wanli favored another son.

In 1578, Wanli married Wang Xijie, who became the empress. She had one daughter but no sons. Wanli did not have a good relationship with her and preferred Lady Zheng. The empress maintained a dignified public image and supported Wanli's eldest son. She died in April 1620, a few months before the emperor.

Lady Wang, a palace servant, became pregnant with the emperor's first child in 1581. Although Wanli initially didn't want to acknowledge the child, his mother convinced him. In 1582, Lady Wang gave birth to Zhu Changluo, who would become the Taichang Emperor. Lady Wang was often neglected by the emperor. She was finally given a higher title in 1606 after her grandson (the future Tianqi Emperor) was born. She died in 1611.

Lady Zheng joined the emperor's harem in 1581 and quickly became his favorite. She gave birth to Zhu Changxun in 1586 and was promoted to a very high position. She had six children in total. Her desire for her son, Zhu Changxun, to be the next emperor caused a major political crisis that lasted almost two decades. She was suspected of involvement in an incident in 1615, but nothing was proven. She was also rumored to be responsible for the Taichang Emperor's death, but again, there was no evidence. She died in 1630.

Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Xiaoduanxian, of the Wang clan (孝端顯皇后 王氏; 7 November 1564 – 7 May 1620), personal name Xijie (喜姐)

Titles: Empress (皇后)- Princess Rongchang (榮昌公主; 1582–1647), personal name Xuanying (軒媖), first daughter

- Married Yang Chunyuan (楊春元; 1582–1616) in 1597, and had issue (five sons)

- Princess Rongchang (榮昌公主; 1582–1647), personal name Xuanying (軒媖), first daughter

- Empress Dowager Xiaojing, of the Wang clan (孝靖皇太后 王氏; 27 February 1565 – 18 October 1611)

Titles: Consort Gong (恭妃) → Noble Consort Gong (恭貴妃) → Imperial Noble Consort Cisheng (慈生皇貴妃)- Zhu Changluo, the Taichang Emperor (光宗 朱常洛; 28 August 1582 – 26 September 1620), first son

- Princess Yunmeng (雲夢公主; 1584–1587), personal name Xuanyuan (軒嫄), fourth daughter

- Grand Empress Dowager Xiaoning, of the Zheng clan (孝寧太皇太后 鄭氏; 1565–1630)

Titles: Imperial Concubine Shu (淑嬪) → Consort De (德妃) → Noble Consort (貴妃)- Princess Yunhe (雲和公主; 1584–1590), personal name Xuanshu (軒姝), second daughter

- Zhu Changxu, Prince Ai of Bin (邠哀王 朱常溆; 19 January 1585), second son

- Zhu Changxun, Prince Zhong of Fu (福忠王 朱常洵; 22 February 1586 – 2 March 1641), third son

- Zhu Changzhi, Prince Hai of Yuan (沅懷王 朱常治; 10 October 1587 – 5 September 1588), fourth son

- Princess Lingqiu (靈丘公主; 1588–1589), personal name Xuanyao (軒姚), sixth daughter

- Princess Shouning (壽寧公主; 1592–1634), personal name Xuanwei (軒媁), seventh daughter

- Married Ran Xingrang (冉興讓; d. 1644) in 1609, and had issue (one son)

- Grand Empress Dowager Xiaojing, of the Li clan (孝敬太皇太后 李氏; d. 1597)

Titles: Consort (妃)- Zhu Changrun, Prince of Hui (惠王 朱常潤; 7 December 1594 – 29 June 1646), sixth son

- Zhu Changying, Prince Duan of Gui (桂端王 朱常瀛; 25 April 1597 – 21 December 1645), seventh son

- Consort Xuanyizhao, of the Li clan (宣懿昭妃; 1557–1642)

- Consort Ronghuiyi, of the Yang clan (榮惠宜妃 楊氏; d. 1581)

- Consort Wenjingshun, of the Chang clan (溫靜順妃 常氏; 1568–1594)

- Consort Duanjingrong, of the Wang clan (端靖榮妃 王氏; d. 1591)

- Princess Jingle (靜樂公主; 8 July 1584 – 12 November 1585), personal name Xuangui (軒媯), third daughter

- Consort Zhuangjingde, of the Xu clan (莊靖德妃 許氏; d. 1602)

- Consort Duan, of the Zhou clan (端妃 周氏)

- Zhu Changhao, Prince of Rui (瑞王 朱常浩; 27 September 1591 – 24 July 1644), fifth son

- Consort Qinghuishun, of the Li clan (清惠順妃 李氏; d. 1623)

- Zhu Changpu, Prince Si of Yong (永思王 朱常溥; 1604–1606), eighth son

- Princess Tiantai (天台公主; 1605–1606), personal name Xuanmei (軒媺), tenth daughter

- Consort Xi, of the Wang clan (僖妃 王氏; d. 1589)

- Concubine De, of the Li clan (德嬪 李氏; 1567–1628)

- Princess Xianju (仙居公主; 1584–1585), personal name Xuanji (軒姞), fifth daughter

- Princess Taishun (泰順公主; d. 1593), personal name Xuanji (軒姬), eighth daughter

- Princess Xiangshan (香山公主; 1598–1599), personal name Xuandeng (軒嬁), ninth daughter

- Concubine Shen, of the Wei clan (慎嬪 魏氏; 1567–1606)

- Concubine Jing, of the Shao clan (敬嬪 邵氏; d. 1606)

- Concubine Shun, of the Zhang clan (順嬪 張氏; d. 1589)

- Concubine He, of the Liang clan (和嬪 梁氏; 1562–1643)

- Concubine Dao, of the Geng clan (悼嬪 耿氏; 1568–1589)

- Shiyu, of the Hu clan (侍御 胡氏)

- Noble Lady, of the Guo clan (貴人 郭氏)

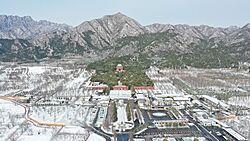

The Emperor's Tomb

The Wanli Emperor was buried in the Ming tombs, located near Beijing. This area is the final resting place for thirteen of the sixteen Ming emperors. The Wanli Emperor's tomb, called Dingling Mausoleum, was built between 1584 and 1590. It has three walled courtyards and a large sacrificial hall.

In 1956–1957, archaeologists explored the underground part of the tomb. They found an entrance hall, an outer hall, a middle hall, and the main burial chamber. The burial chamber is very large, measuring 9.1 by 30 meters and 9.5 meters high. Inside, they found wooden coffins with the remains of the emperor, his empress, and the mother of the Taichang Emperor. Over three thousand objects were also discovered, including jewelry, gold and silver items, jade, porcelain, clothing, and the emperor's and empress's crowns.

Unfortunately, the archaeological survey in the 1950s was not done with the best methods, and many wooden and textile artifacts could not be preserved. Also, many of the discovered objects, including the remains of the emperor and his wives, were destroyed later during the Cultural Revolution.

See also

In Spanish: Emperador Wanli para niños

In Spanish: Emperador Wanli para niños

- Chinese emperors family tree (late)

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |