Zhou dynasty facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Zhou

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1046 BC – 256 BC | |||||||||||

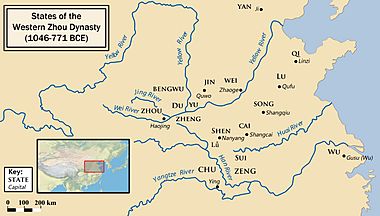

Population concentration and boundaries of the Western Zhou dynasty (1050–771 BC) in China

|

|||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Chinese | ||||||||||

| Religion | Chinese folk religion, Ancestor worship, Heaven worship | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

|

• c. 1046–1043 BC

|

King Wu | ||||||||||

|

• 781–771 BC

|

King You | ||||||||||

|

• 770–720 BC

|

King Ping | ||||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

|

• Battle of Muye

|

c. 1046 BC | ||||||||||

|

• Gonghe Regency

|

841–828 BC | ||||||||||

|

• Relocation to Wangcheng

|

771 BC | ||||||||||

| 256 BC | |||||||||||

|

• Fall of the last Zhou holdouts

|

249 BC | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

|

• 273 BC

|

30,000,000 | ||||||||||

|

• 230 BC

|

38,000,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Mostly spade coins and knife coins | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||||

| Zhou | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

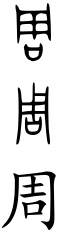

"Zhou" in ancient bronze script (top), seal script (middle), and regular script (bottom) Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 周 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

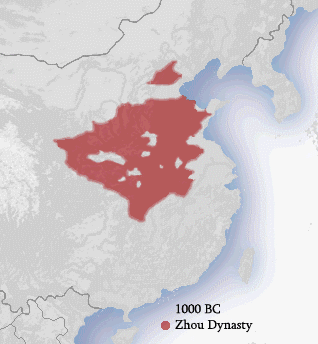

The Zhou dynasty (Chinese: 周; pinyin: Zhōu [ʈʂóu̯]) was a long-lasting royal family that ruled China. It followed the Shang dynasty and lasted for about 789 years, from 1046 BC to 256 BC. This makes it the longest dynasty in Chinese history.

The Zhou royal family, whose last name was Ji, had strong military control over ancient China from 1046 BC to 771 BC. This time is called the Western Zhou period. Even after that, their political influence continued for another 500 years during the Eastern Zhou period.

Over time, the Zhou kings' power became weaker. This was especially true during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period. During the Warring States period, the Zhou court had very little control. Different states fought each other until the Qin state took over and formed the Qin dynasty in 221 BC. The Zhou dynasty officially ended 35 years before that, but they had almost no real power by then.

This period was a golden age for making beautiful Chinese bronzeware. It was also when three major Chinese philosophies began: Confucianism, Taoism, and Legalism. The way Chinese characters were written also changed a lot during the Zhou dynasty. They went from oracle script and bronze script to seal script, and then to a form very similar to modern writing.

Contents

History of the Zhou Dynasty

How the Zhou Dynasty Began

Ancient Stories of the Zhou

Ancient Chinese stories say the Zhou family started in a special way. A woman named Jiang Yuan became pregnant after stepping into a giant footprint left by a god. Her son, Qi, was called "the Abandoned One" because his mother left him three times, but he survived.

Qi was a hero who greatly improved farming. Because of this, he was given land, the family name Ji, and the title "Lord of Millet". People even worshipped him as a god of harvests.

Later, a descendant named Liu led his people to a place called Bin. He made them rich by bringing back good farming methods. Many generations of his family ruled there. Then, Tai moved the clan from Bin to Zhou, an area in the Wei River valley.

The duke chose his youngest son, Jili, to be his successor, even though he had two older sons. Jili was a strong warrior. He fought and conquered several tribes for the Shang kings. But the Shang forces later killed him unfairly.

Jili's son, Wen, managed to get out of prison and moved the Zhou capital to Feng. Around 1046 BC, Wen's son, Wu, and his helper, Jiang Ziya, led a large army. They crossed the Yellow River and defeated the last Shang king, King Zhou of Shang, at the Battle of Muye. This battle marked the start of the Zhou dynasty. The Zhou even gave land to a member of the defeated Shang royal family, letting them rule the state of Song.

Zhou Culture and Language

The Zhou people seemed to speak a language very similar to the Shang. They also copied many Shang cultural practices. This might have been to show that they were the rightful rulers after the Shang.

However, the Zhou might also have been connected to the Xirong, a group of people living west of the Shang. The Shang saw the Xirong as groups who paid tribute to them. Some ancient texts suggest that King Wen of Zhou had Xirong ancestors. This shows that the Zhou were influenced by different cultures.

Western Zhou Period (1046–771 BC)

After winning the war, King Wu kept the old Shang capital for ceremonies. But he built a new capital called Hao for his palace and government. King Wu died soon after, leaving a young son as heir. His uncle, the Duke of Zhou, helped the young King Cheng become a strong ruler.

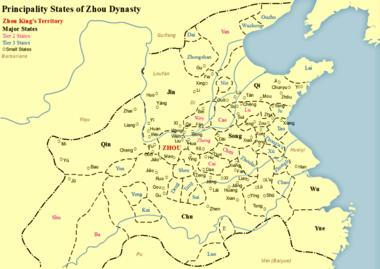

Some Zhou princes in the east rebelled against the Duke of Zhou. They had support from other nobles and Shang followers. But the Duke of Zhou stopped the rebellion and expanded the Zhou kingdom further east. To keep control over this large area, he set up a system called fengjian.

He also created the idea of the Mandate of Heaven. This idea said that the Zhou had the right to rule because Heaven (a divine power) had chosen them. This helped make their rule seem fair and legitimate.

Over time, the fengjian system became weaker. The family ties between the Zhou kings and the local rulers became distant. Areas far from the capital grew stronger and became as important as the Zhou kings.

In 771 BC, King You of Zhou made his queen leave to favor another woman. The queen's father, the Marquis of Shen, joined with other groups, including the Quanrong "barbarians." They attacked and destroyed the capital, Hao. King You was killed.

After King You's death, nobles chose the Marquis of Shen's grandson, King Ping of Zhou, as the new king. The capital was moved east to Wangcheng. This marked the end of the "Western Zhou" period and the start of the "Eastern Zhou" dynasty.

Eastern Zhou Period (771–256 BC)

The Eastern Zhou period saw the royal family's power quickly disappear. However, the king's role in rituals kept him important for over 500 more years. The early part of this period is called the "Spring and Autumn" period.

Later, around the mid-5th century BC, the ""Warring States"" began. In 403 BC, the Zhou court recognized three states—Han, Zhao, and Wei—as fully independent. Soon, other rulers also started calling themselves "king," showing they no longer pretended to be under the Zhou court.

Many states became powerful and then fell. The Zhou was a small player in most of these wars. The last Zhou king was Nan. He was killed when the Qin state captured the capital Wangcheng in 256 BC. Although another "King Hui" was declared, his small state was gone by 249 BC. The Qin state finally united all of China in 221 BC.

The Eastern Zhou period is also known as a golden age for Chinese philosophy. Many different ideas and schools of thought appeared, called the Hundred Schools of Thought. Lords supported scholars who traveled around, sharing their ideas. The most famous example was Qi's Jixia Academy.

Nine main schools of thought became very important: Confucianism, Legalism, Taoism, Mohism, Agriculturalism, two types of Diplomatists, Logicians, Militarists, and Naturalists. Even though only the first three became officially supported later, all of them influenced Chinese society in different ways.

Culture and Society in Zhou China

The main area of the Zhou dynasty was the Wei River valley. This remained their most important power base after they conquered the Shang.

The Mandate of Heaven: Why the Zhou Ruled

The Zhou rulers introduced a very important idea called the "Mandate of Heaven." They said that they were morally better than the Shang. Because of this, Heaven had given them the right to take over the Shang's land and wealth. They claimed Heaven wanted them to bring good government back to the people.

The Mandate of Heaven was like a promise between the Zhou people and their main god, Heaven. The Zhou believed that Heaven chose only one person, the Zhou ruler, to have legitimate power on Earth. In return, the ruler had to follow Heaven's rules of harmony and honor.

If a ruler failed in these duties, if there was chaos, or if the people suffered, that ruler would lose the Mandate. Then, Heaven could take away its support and choose a new, more worthy ruler. This idea helped the Zhou explain why they had replaced the Shang.

The Zhou kings had to admit that even they could lose the Mandate of Heaven if they ruled badly. Old poems from the Zhou period warned about this. The Zhou kings said that Heaven favored them because the last Shang kings were evil and caused suffering. After the Zhou took power, the Mandate became a powerful political tool.

One of the king's duties was to create a royal calendar. This calendar told people when to farm and when to hold important ceremonies. But unexpected events, like solar eclipses or natural disasters, made people question the ruler's power. Since rulers claimed their power came from Heaven, the Zhou worked hard to understand the stars and improve their astronomical system for the calendar.

The Zhou also showed their power by using bronze ritual vessels, statues, and weapons, just like the Shang. The Zhou copied the Shang's large-scale production of ceremonial bronzes. They forced many Shang people to make these bronze objects. These objects were then sold and spread across the land, showing that the Zhou were the new legitimate rulers.

The Feudal System of Zhou China

Many Western writers describe the Zhou period as "feudal." This is because the Zhou's fēngjiàn system had similarities to the medieval rule in Europe.

Both systems were decentralized. When the Zhou dynasty began, the conquered land was divided into hereditary areas called fiefs (zhūhóu). These fiefs were given to loyal nobles and eventually became powerful states on their own. In terms of inheritance, the Zhou dynasty only allowed the eldest son to inherit everything.

This system, called "extensive stratified patrilineage," meant that the eldest son of each generation continued the main family line and political power. Younger brothers would start new, less powerful family lines. The further away a line was from the main one, the less political power it had.

Fēngjiàn System and Government Officials

There were five ranks of nobles below the king: duke, marquis, count, viscount, and baron. Sometimes, a strong duke would take power from his nobles and make his state more centralized. Centralization became more important as states started fighting each other. If a duke took power from his nobles, the state would be run by appointed officials.

Despite these similarities, there were important differences from medieval Europe. The Zhou rulers lived in walled cities, not castles. China also had a different class system. There was no organized clergy. Instead, people from Shang families became experts in rituals, ceremonies, astronomy, and government. They were known as ru.

When a dukedom became centralized, these ru would become government officials or officers. These hereditary classes were similar to European knights in their status. But unlike European knights, they were expected to be scholars, not just warriors. Since they were appointed, they could move from one state to another. Some traveled around, offering ideas for improving government or military.

Those who couldn't find government jobs often taught young men who wanted to become officials. The most famous of these teachers was Confucius. He taught a system of mutual duty between people of different ranks. In contrast, the Legalists believed in strict laws and harsh punishments. The wars of the Warring States period were finally ended by the Qin state, which followed Legalist ideas. When the Qin dynasty fell, many Chinese people were happy to return to the more humane ideas of Confucius.

Farming and Water Projects

Farming during the Zhou dynasty was very important and often managed by the government. All farmland was owned by nobles, who then gave it to their serfs (farmers who were tied to the land). This was similar to European feudalism.

For example, land was divided into nine squares in the "well-field system." The government took the grain from the middle square, and individual farmers kept the grain from the surrounding squares. This way, the government could store extra food and give it out during famines or bad harvests. Important industries during this time included bronze making, which was vital for weapons and farming tools. Nobles also controlled these industries.

China's first large-scale water projects began during the Zhou dynasty. These projects were mainly to help with irrigation for farming. A chancellor of Wei, Sunshu Ao, built a dam to create a huge irrigation reservoir. He is known as China's first hydraulic engineer. Later, another Wei statesman, Ximen Bao, created a large system of irrigation canals. His project redirected the waters of the entire Zhang River to the Yellow River.

Zhou Military Power

The early Western Zhou had a strong army, divided into two main groups: "the Six Armies of the west" and "the Eight Armies of Chengzhou." These armies fought in the northern Loess Plateau, modern Ningxia, and the Yellow River floodplain.

The Zhou military was strongest during the 19th year of King Zhao's rule. However, the six armies were destroyed, and King Zhao died during a campaign near the Han River. Early Zhou kings were true military leaders. They constantly fought against "barbarians" on behalf of the small states called guo.

King Zhao was known for his many campaigns in the Yangtze areas and died in his last battle. Later kings were less successful. King Li led 14 armies against southern "barbarians" but did not win. King Xuan fought the Quanrong nomads without success. King You was killed by the Quanrong when Haojing was attacked.

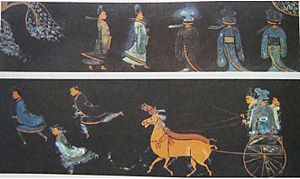

Although chariots came to China during the Shang dynasty, the Zhou period was when they were first widely used in battles. Recent discoveries show similarities between horse burials of the Shang and Zhou dynasties and those of Indo-European people in the west. This suggests possible cultural influences, like fighting styles or art, from contact with these groups.

The Zhou army also included "Barbarian" troops, such as the Di people. King Hui of Zhou married a princess from the Red Di to show how important the Di troops were. King Xiang of Zhou also married a Di princess after getting military help from the Di.

Zhou Philosophy and Ideas

During the Zhou dynasty, the first ideas of native Chinese philosophy began to grow, starting in the 6th century BC. The most important Chinese philosophers, who greatly influenced later generations, were Confucius, who started Confucianism, and Laozi, who started Taoism.

Other thinkers and schools of thought from this time included Mozi, who founded Mohism; Mencius, a famous Confucian who expanded on Confucius's ideas; Shang Yang and Han Fei, who developed ancient Chinese Legalism (the main philosophy of the Qin dynasty); and Xun Zi, who was a very central intellectual figure in his time.

The Zhou dynasty's official religion used ideas from the Shang dynasty. They mostly referred to the Shang god, Di, as Tian (Heaven). Tian was seen as a more distant and mysterious concept that anyone could connect with. The Zhou wanted to encourage more people to seek enlightenment and learn about these spiritual ideas. This was a way to move their people away from the Shang-era beliefs and local traditions.

Li: Rules for Life

The Li (traditional Chinese: 禮; simplified Chinese: 礼; pinyin: lǐ) ritual system was created during the Western Zhou period. It was a set of rules for good manners that showed social hierarchy, ethics, and how people should live. These social practices became very important in Confucian thought.

This system was later written down in books like the Book of Rites during the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). It became a core part of Chinese imperial ideas. At first, Li was a respected set of clear rules. But as the Western Zhou period broke apart, these rituals became more about morals and formal rules for things like:

- The five ranks of Chinese nobility.

- The size and number of buildings for ancestral temples.

- Rules for ceremonies, such as the number of ritual vessels, musical instruments, and dancers.

Kings of the Zhou Dynasty

The rulers of the Zhou dynasty were called Wáng (王), which means "king" in English. This was also the term the Shang used for their rulers.

Before King Wu, his ancestors—Danfu, Jili, and Wen—are also called "Kings of Zhou." This is even though they were officially under the Shang kings.

Please note: Dates in Chinese history before 841 BC are debated and can differ between sources. The dates below are from the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project and Edward L. Shaughnessy's The Absolute Chronology of the Western Zhou Dynasty.

| Personal name | Posthumous name | Reign period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 發 | Fa | 周武王 | King Wu of Zhou | 1046–1043 BC 1045–1043 BC |

| 誦 | Song | 周成王 | King Cheng of Zhou | 1042–1021 BC 1042/1035–1006 BC |

| 釗 | Zhao | 周康王 | King Kang of Zhou | 1020–996 BC 1005/1003–978 BC |

| 瑕 | Xia | 周昭王 | King Zhao of Zhou | 995–977 BC 977/975–957 BC |

| 滿 | Man | 周穆王 | King Mu of Zhou | 976–922 BC 956–918 BC |

| 繄扈 | Yihu | 周共王/周龔王 | King Gong of Zhou | 922–900 BC 917/915–900 BC |

| 囏 | Jian | 周懿王 | King Yi of Zhou | 899–892 BC 899/897–873 BC |

| 辟方 | Pifang | 周孝王 | King Xiao of Zhou | 891–886 BC 872?–866 BC |

| 燮 | Xie | 周夷王 | King Yi of Zhou | 885–878 BC 865–858 BC |

| 胡 | Hu | 周厲王/周剌王 | King Li of Zhou | 877–841 BC 857/853–842/828 BC |

| 共和 | Gonghe Regency | 841–828 BC | ||

| 靜 | Jing | 周宣王 | King Xuan of Zhou | 827–782 BC |

| 宮湦 | Gongsheng | 周幽王 | King You of Zhou | 781–771 BC |

| End of Western Zhou / Beginning of Eastern Zhou | ||||

| 宜臼 | Yijiu | 周平王 | King Ping of Zhou | 770–720 BC |

| 林 | Lin | 周桓王 | King Huan of Zhou | 719–697 BC |

| 佗 | Tuo | 周莊王 | King Zhuang of Zhou | 696–682 BC |

| 胡齊 | Huqi | 周僖王 | King Xi of Zhou | 681–677 BC |

| 閬 | Lang | 周惠王 | King Hui of Zhou | 676–652 BC |

| 鄭 | Zheng | 周襄王 | King Xiang of Zhou | 651–619 BC |

| 壬臣 | Renchen | 周頃王 | King Qing of Zhou | 618–613 BC |

| 班 | Ban | 周匡王 | King Kuang of Zhou | 612–607 BC |

| 瑜 | Yu | 周定王 | King Ding of Zhou | 606–586 BC |

| 夷 | Yi | 周簡王 | King Jian of Zhou | 585–572 BC |

| 洩心 | Xiexin | 周靈王 | King Ling of Zhou | 571–545 BC |

| 貴 | Gui | 周景王 | King Jing of Zhou | 544–521 BC |

| 猛 | Meng | 周悼王 | King Dao of Zhou | 520 BC |

| 丐 | Gai | 周敬王 | King Jing of Zhou | 519–476 BC |

| 仁 | Ren | 周元王 | 475–469 BC | |

| 介 | Jie | 周貞定王 | King Zhending of Zhou | 468–442 BC |

| 去疾 | Quji | 周哀王 | King Ai of Zhou | 441 BC |

| 叔 | Shu | 周思王 | King Si of Zhou | 441 BC |

| 嵬 | Wei | 周考王 | King Kao of Zhou | 440–426 BC |

| 午 | Wu | 周威烈王 | King Weilie of Zhou | 425–402 BC |

| 驕 | Jiao | 周安王 | King An of Zhou | 401–376 BC |

| 喜 | Xi | 周烈王 | King Lie of Zhou | 375–369 BC |

| 扁 | Bian | 周顯王 | King Xian of Zhou | 368–321 BC |

| 定 | Ding | 周慎靚王 | King Shenjing of Zhou | 320–315 BC |

| 延 | Yan | 周赧王 | King Nan of Zhou | 314–256 BC |

After the capital, Chengzhou, fell to Qin forces in 256 BC, nobles from the Ji family declared Duke Hui of Eastern Zhou as King Nan's successor. Ji Zhao, a son of King Nan, led a fight against Qin for five years. But this small dukedom fell in 249 BC. The rest of the Ji family ruled in Yan and Wei until 209 BC.

During Confucius's time in the Spring and Autumn Period, the Zhou kings had very little power. Most of the government work and real political strength was held by the rulers of smaller areas and local community leaders.

Astrology and the Zhou Dynasty

In traditional Chinese astrology, the Zhou dynasty is linked to two stars. These are Eta Capricorni (called "the First Star of Zhou") and 21 Capricorni (called "the Second Star of Zhou"). Both are part of the "Twelve States" star group. The Zhou is also represented by the star Beta Serpentis in the "Right Wall" group, which is part of the Heavenly Market enclosure in Chinese constellations.

See also

Template:Kids robot.svg In Spanish: Dinastía Zhou para niños

- Family tree of the Zhou dynasty

- Four occupations

- Historical capitals of China

- Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng

- Women in ancient and imperial China

- Ritual and music system

- Patriarchal system (Western Zhou)

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |