Chinese art facts for kids

Chinese art is all the amazing visual art that comes from China. It also includes art made by Chinese artists living outside China, especially if it uses Chinese culture, history, or traditions. Chinese art goes way back, starting around 10,000 BC with simple pottery and sculptures.

For a long time, Chinese art was grouped by the different ruling families, called dynasties. Most of these dynasties lasted for hundreds of years. You can see huge collections of Chinese art at the Palace Museum in Beijing and the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

Chinese art is special because it has a strong connection to its past. It didn't have big breaks like Western art did. Things like pottery, textiles, and carved lacquer are very important in Chinese art. Many of the best pieces were made in large workshops by artists whose names we don't know today.

These workshops often worked for the Emperor, creating beautiful items. These items were used by the royal family and also sent to other countries to show off China's wealth and power. However, there was also a different kind of art: ink wash painting. This was often done by scholar-officials and court painters. They focused on landscapes, flowers, and birds, showing their own feelings and observations. In recent years, Chinese artists have also become very successful in the world of contemporary art.

Contents

- A Journey Through Chinese Art History

- Ancient Pottery: Neolithic Times

- Jade Art: A Special Stone

- Bronze Casting: Powerful and Detailed

- Zhou Dynasty Art (Around 1046 – 256 BCE)

- Early Imperial China (221 BCE – 220 CE)

- Art During a Divided China (220–581 CE)

- The Sui and Tang Dynasties (581–960 CE)

- The Song and Yuan Dynasties (960–1368 CE)

- Late Imperial China (1368–1911 CE)

- Chinese Painting Styles

- Sculpture: From Bronzes to Buddhas

- Ceramics: The Art of Pottery

- Decorative Arts: Beauty in Everyday Objects

- Architecture: Building with Tradition

- Chinoiserie: European Take on Chinese Style

- Modern Chinese Art: New Beginnings

- The Art Market: A Growing Global Presence

- Where to See Chinese Art

- See also

A Journey Through Chinese Art History

Ancient Pottery: Neolithic Times

Early Chinese art can be found in the Yangshao culture, which existed around 6,000 BC. Archeologists have found that the Yangshao people made pottery. Their first decorations were simple fish and human faces. Later, they created cool, balanced geometric designs, some of which were painted.

The Yangshao culture is famous for its painted pottery. They didn't use pottery wheels like later cultures did. It's interesting to know that children were sometimes buried in these painted pottery jars.

-

Dotted pottery pot, semi-mountain type; by Yangshao culture from China; 2700–2300 BCE; Gansu Provincial Museum (Lanzhou)

-

Jar; 2650–2350 BC; earthenware with painted decoration; height: 34 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Jade Art: A Special Stone

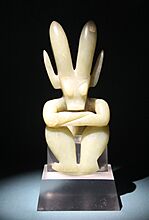

The Liangzhu culture was the last group to use jade during the New Stone Age in the Yangtze River Delta. This culture lasted for about 1,300 years. Their jade pieces are known for being very detailed and large. They made ritual objects like Cong cylinders and Bi discs. They also created pendants and decorations shaped like birds, turtles, and fish. Liangzhu jade often looks white and milky, like bone, because of the type of stone it came from and how it was buried.

-

Cong, 3rd millenium BCE

Bronze Casting: Powerful and Detailed

The Bronze Age in China began with the Xia dynasty. During this time, people made useful objects from bronze. Later, in the Shang dynasty, artists created more detailed bronze items, including many for religious ceremonies. Shang bronzesmiths were famous for their clear and precise work. They often made ritual vessels, weapons, and parts for chariots.

These bronze vessels were used to hold food and drinks for sacred ceremonies. Some, like the ku and jue, were very elegant. The most impressive pieces were the ding, which looked very strong and powerful.

Shang bronzes were usually decorated everywhere, often with designs of real and imaginary animals. A common design was the taotie. This showed a mythical creature's face, flattened out to create a balanced design. The meaning of taotie is not fully clear, but old stories say it might have been a greedy monster.

Over time, bronze objects changed. In the Zhou dynasty, they became more practical and less religious. By the Warring States period, people enjoyed them just for their beauty. Some were decorated with scenes of banquets or hunts. Others had abstract patterns made with gold, silver, or precious stones.

Bronze items were also important in the Han dynasty, especially for burials. Many bronze vessels found in tombs show the beauty of Han art. These vessels, like the Ding, Hu, and Xun, were used to connect with the spirits of ancestors. Besides vessels, tombs also contained bronze weapons, daily items, and musical instruments. Owning a full set of Bianzhong bells showed a person's high status, as only rich and royal families had them. These bells were also used to communicate with gods.

People started to appreciate Shang bronzes as art during the Song dynasty. They loved their shapes, designs, and the beautiful colors (like green, blue-green, and reddish) that formed on the bronze over time from being buried.

-

Longshan goblet; circa 2500–2000 BC; Excavated at Jiaoxian in Shandong, 1975)

-

Altar set; late 11th century BC; bronze; overall (table): height: 18.1 cm (71⁄8 in.), width: 46.4 cm (181⁄4 in.), depth: 89.9 cm (353⁄8 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, U.S.)

-

Houmuwu ding, the largest ancient bronze ever found; 1300–1046 BCE; National Museum of China.

-

Ritual wine server (guang); 1100 BC; Indianapolis Museum of Art.

-

Taibao Ding from the Western Zhou, unearthed in Shandong; c. 10th century BCE

-

Bell (lai zhong); 800–700 BC (Western Zhou dynasty); 70.3 × 37 × 26.6 cm (275⁄8 × 149⁄16 × 107⁄16 in.); from Meixian, Shaanxi); Cleveland Museum of Art. In ancient China music and ritual had political significance and were linked inseparably to the power of states

-

A bronze stand for ceremonial vessels; excavated from the tomb of the son of King Zhuang of Chu (r. 613–591 BCE)

Zhou Dynasty Art (Around 1046 – 256 BCE)

During the Zhou period, artists started making sculptures of human figures. Some of the earliest examples include wooden figures from Shaanxi and statuettes of bronze musicians. One very old sculpture is the Taerpo horserider, a terracotta figure of a cavalryman from a tomb. This shows that people were riding horses in battle back then.

-

Spring and Autumn Period ox-shaped vessel, 6th century BCE

Art from the Chu State

The state of Chu, located in the Yangtze River valley, was a rich source of early Chinese art. When archaeologists dug up Chu tombs, they found painted wooden sculptures, jade disks, glass beads, musical instruments, and many kinds of lacquerware. Many of these lacquer objects were beautifully painted, often red on black or black on red. Some of the oldest paintings on silk were found in Changsha, Hunan province.

-

Heart-shaped lacquer box with phoenix pattern.

-

The Fenghuang was a popular motif in Chu art, whereas the dragon was more popular in the other states to its north.

Early Imperial China (221 BCE – 220 CE)

Qin Dynasty Art: The Terracotta Army

The Terracotta Army is an amazing collection of more than 7,000 life-sized clay figures of warriors and horses. They were buried with the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, around 210 BC. These figures were meant to protect him in the afterlife.

When they were first found, the figures were painted with bright colors. But when they touched the air, the colors faded. Now, they look like their natural clay color. The figures show different poses, like standing soldiers and kneeling archers. Each head looks unique, with different faces, expressions, and hairstyles. This incredible realism shows how advanced art was during the Qin dynasty.

A musical instrument called the Qin zither was also developed during this time. In China, the beauty of a musical instrument was always as important as how it sounded. The Qin zither has seven strings and is often seen as a symbol of peace and harmony.

Han Dynasty Art: Jade, Bronze, and Landscapes

The Han dynasty was famous for its jade burial suits. One of the earliest landscape pictures in Chinese art comes from a Han dynasty tomb. It shows a scene with roads and garden walls that make it look like you are looking down from a hill. This was made by pressing stamps onto soft clay. However, the oldest known landscape painting in the traditional sense is by Zhan Ziqian from the Sui dynasty (581–618).

Besides jade, bronze was also a favorite material for artists because it was strong. Bronze mirrors were made in large numbers during the Han dynasty. Almost every Han tomb found has a mirror inside. The shiny side was usually made of bronze, copper, tin, and lead. In China, mirrors were seen as a way to reflect reality and remember past events. The non-shiny side of Han bronze mirrors often had detailed decorations and stories.

-

Abstract yet intricate patterns were found on coffins of lady Xin Zhui (217 BC–168 BC)

-

Musicians playing guzheng and sheng, 2nd century BCE

-

These figures represent guardian spirits of certain hours of the day- the left figure represents the first hour (midnight).

-

Han couple banquet together, from Luoyang c. 220 CE

-

Bronze statuette of a qilin, 1st century AD

-

Western Han tomb fresco depicting the philosopher Confucius; 202 BCE – 9 CE; from Dongping County, Shandong

-

Two gentlemen engrossed in conversation while two others look on, a painting on a ceramic tile from a tomb near Luoyang, Henan, dated to the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD)

-

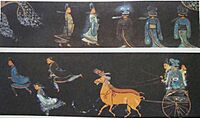

A section of an Eastern Han (25–220 AD) fresco of 9 chariots, 50 horses, and over 70 men, from a tomb in Luoyang, China

-

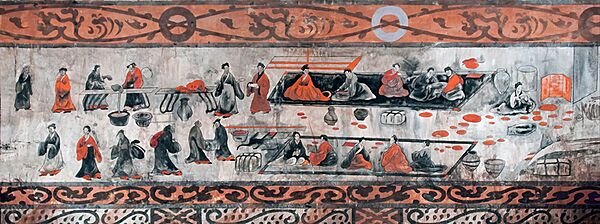

Mural of the Dahuting Tomb (打虎亭漢墓; Dáhǔtíng hàn mù) of the late Eastern Han, located in Zhengzhou

-

An Eastern Han ceramic figurine of a seated woman with a bronze mirror, unearthed from a tomb of Songjialin, Pi County, Sichuan

First Monumental Stone Sculptures

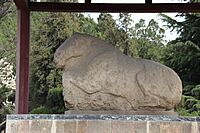

While small clay figures were common, large stone statues were rare in China before the Mausoleum of Huo Qubing (140–117 BCE). Huo Qubing was a general who fought against the Xiongnu. The most famous statue at his tomb is a horse trampling a Xiongnu warrior.

Huo Qubing's Mausoleum has 15 other stone sculptures. These statues often kept the natural shape of the stone, with details carved in high-relief. After these early attempts, large stone statues became more common from the late Western Han to the Eastern Han periods. Monumental stone statues became a major art form from the 4th to 6th centuries CE, especially with the rise of large Buddhist sculptures in China.

Art During a Divided China (220–581 CE)

The Influence of Buddhism on Art

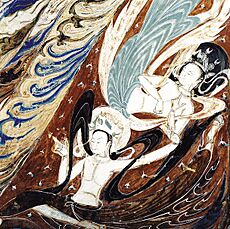

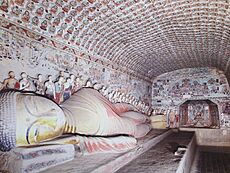

Buddhism arrived in China around the 1st century CE. From then until the 8th century, it greatly influenced Chinese art, especially statues. China quickly added its own unique style to Buddhist art.

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the Northern dynasties developed a more symbolic and abstract style for Buddhist art. Their statues looked serious and grand. Over time, artists wanted to make Buddhist art more realistic. This led to the very lifelike style of Tang Buddhist art.

-

Dunhuang mural, mid 6th century

Calligraphy: The Art of Writing

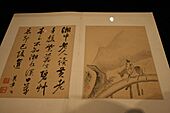

In ancient China, painting and calligraphy (beautiful writing) were the most respected arts. They were mostly done by wealthy people and government officials who had time to practice. Calligraphy was even thought to be the highest form of painting.

Artists used a brush made of animal hair and black ink from pine soot. They wrote and painted on silk, but after paper was invented in the 1st century, paper became more common. Famous calligraphers' original writings were highly valued. They were often put on scrolls and hung on walls, just like paintings.

Wang Xizhi was a very famous Chinese calligrapher from the 4th century AD. His most well-known work is the Lanting Xu, a preface to a poetry collection. It's considered a masterpiece of the "Running Style" of calligraphy.

Wei Shuo was another important calligrapher who set rules for the "regular script" style. Her famous works include Famous Concubine Inscription.

Painting: Capturing Life and Nature

Gu Kaizhi was a celebrated painter from ancient China. He wrote three books about painting ideas. He believed that in figure paintings, the clothes and looks weren't as important as the eyes, which showed the spirit.

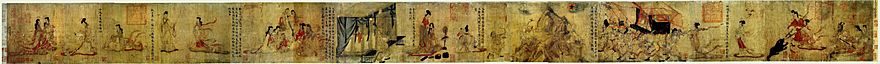

Three of Gu's paintings still exist today: Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies, Nymph of the Luo River, and Wise and Benevolent Women.

Other paintings from the Jin dynasty have been found in tombs. These include Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, painted on a brick wall. Each figure is labeled and shown doing things like drinking or playing music. Other tomb paintings show daily life, such as men plowing fields with oxen.

-

A scene of two horseback riders from a wall painting in the tomb of Lou Rui at Taiyuan, Shanxi, Northern Qi dynasty (550–577)

-

Northern Wei murals and painted figurines from the Yungang Grottoes, dated 5th to 6th centuries.

The Sui and Tang Dynasties (581–960 CE)

Buddhist Art and Architecture

After the Sui dynasty, Buddhist sculptures in the Tang period became very lifelike. Because the Tang dynasty was open to foreign trade and ideas through the Silk Road, Tang Buddhist sculptures took on a classical look, inspired by art from Central Asia.

However, towards the end of the Tang dynasty, foreign influences were seen negatively. In 845, Emperor Wuzong banned all "foreign" religions, including Buddhism, to support local Taoism. He took away Buddhist property and forced the religion to go underground. This affected how Buddhist art developed in China.

Glazed or painted clay figures from Tang dynasty tombs are very famous and can be seen in museums worldwide. Most wooden Tang sculptures haven't survived, but you can still see examples of the Tang international style in Nara, Japan. Stone sculptures have lasted much longer. Some of the best examples are at Longmen, Yungang, and Bingling Temple.

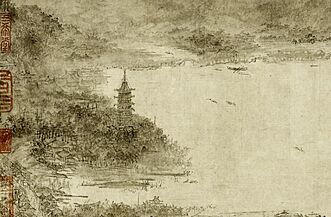

One of the most famous Buddhist Chinese pagodas is the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, built in 652 AD.

-

Tang dynasty painting from Dunhuang.

-

Fresco from Dunhuang depicting typical Tang architecture

-

A Chinese Tang dynasty tri-color glazed porcelain horse (c. 700 AD), using yellow, green and white colors.

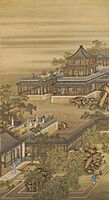

Tang Dynasty Painting: Landscapes and Court Life

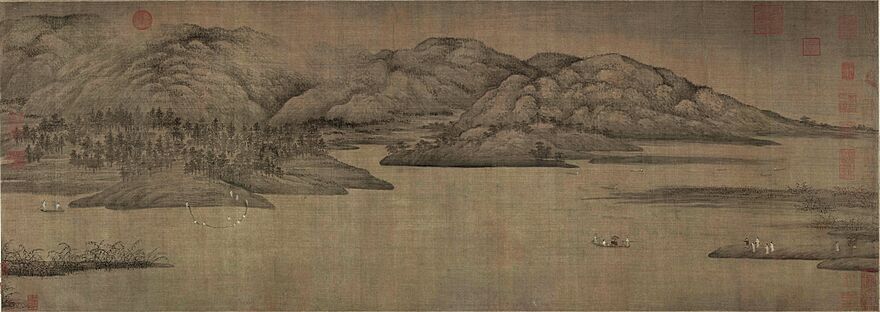

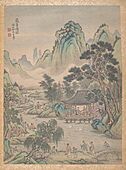

Starting in the Tang dynasty (618–907), the main subject of painting became landscapes, known as shanshui (mountain water) painting. These landscapes were usually simple and used only one color of ink. The goal was not to show nature exactly as it looked, but to capture a feeling or mood, and to show the "rhythm" of nature.

Traditional painting used the same tools as calligraphy: a brush dipped in black or colored ink. Oils were not used. Paper and silk were the most popular materials. Finished paintings were mounted on scrolls that could be hung or rolled up. Paintings were also made in albums, on walls, on lacquerware, and other surfaces.

Dong Yuan was an active painter in the Southern Tang Kingdom. He was known for both people and landscape paintings. His elegant style became the standard for Chinese brush painting for the next 900 years. Like many Chinese artists, he was also a government official. He learned from existing styles but added new techniques, like more complex perspective and using small dots and lines to create vivid effects.

Zhan Ziqian was a painter during the Sui dynasty. His only existing painting is Strolling About In Spring, which shows mountains in perspective. Since pure landscape paintings were rare in Europe until the 17th century, Strolling About In Spring might be the world's first landscape painting.

The Song and Yuan Dynasties (960–1368 CE)

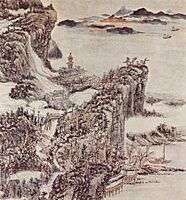

Song Dynasty Painting: Subtle Landscapes and Daily Life

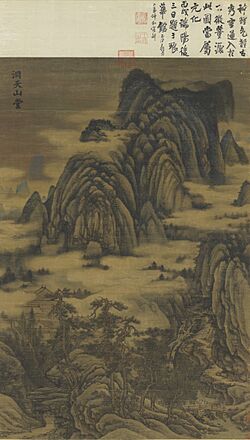

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), landscapes became more subtle. Artists showed huge distances by using blurred outlines and mountains disappearing into mist. They focused on the spiritual side of painting and how the artist could show the harmony between humans and nature, based on Taoist and Buddhist ideas.

Liang Kai was a Chinese painter from the 13th century (Song dynasty) who helped create the Zen school of Chinese art. Wen Tong (11th century) was famous for his ink paintings of bamboo. He could even hold two brushes at once to paint different bamboos! He knew bamboo so well that he didn't need to see it while he painted.

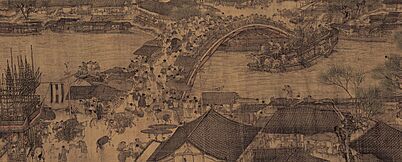

Zhang Zeduan is famous for his long horizontal painting, Along the River During the Qingming Festival. It shows a busy city and landscape scene and is one of China's most famous paintings. Many copies have been made throughout history. Another famous painting is The Night Revels of Han Xizai, which shows wealthy people being entertained by musicians and dancers.

-

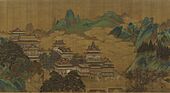

Buddhist Temple in the Mountains, 11th century, ink on silk, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City (Missouri).

-

Seated Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanyin), wood and pigment, 11th century, Chinese Northern Song dynasty, St. Louis Art Museum

-

Three Friends of Winter depicting plum, pine and bamboo, still used for decoration during new year's by countries in the sinosphere

-

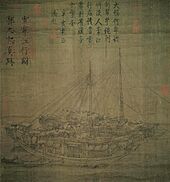

Traveling on the River in Snow. Extremely intricate details give historians insight into medieval Chinese shipbuilding.

-

Emperor Huizong of Song was a prolific painter

-

Loquats and a Mountain Bird, Southern Song (1127–1279); small album leaf paintings like this were popular amongst gentry and scholar-officials.

-

Travelers among Mountains and Streams (谿山行旅), Fan Kuan((c. 960 – 1032)

Yuan Dynasty Painting: Retreat to Nature

When the Song dynasty ended in 1279 and the Mongols took over, many artists left city life. They went back to nature, painting landscapes and bringing back the "blue and green" style from the Tang era.

Wang Meng was one such painter, known for his Forest Grotto. Zhao Mengfu was a scholar, painter, and calligrapher during the Yuan dynasty. He chose an older, simpler style over the fancy brushwork of his time. This change is thought to have started a new era in Chinese landscape painting. Qian Xuan (1235–1305) had served the Song court and refused to work for the Mongols. He turned to painting, bringing back a more Tang dynasty style.

The later Yuan dynasty is known for the "Four Great Masters." Huang Gongwang (1269–1354) created calm and simple landscapes that were admired by artists for centuries. Another important painter was Ni Zan (1301–1374). He often painted with a strong foreground and background, leaving the middle empty. This style was often copied by later Ming and Qing dynasty painters.

Chinese Porcelain: Fine Ceramics

Chinese porcelain is made from a special clay called kaolin and a rock called petuntse. This mixture makes the pottery very hard and smooth. "China" has become a word for high-quality porcelain. Most fine Chinese pottery comes from the city of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province. Jingdezhen porcelain has been a center for porcelain making in China since at least the Yuan dynasty.

Late Imperial China (1368–1911 CE)

Ming Dynasty Painting: Bright Colors and New Ideas

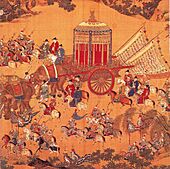

Under the Ming dynasty, Chinese culture flourished. Narrative paintings, which told stories with many colors and busy scenes, were very popular.

Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) developed the style of the Wu school in Suzhou. This style was very important in Chinese painting during the 16th century.

European culture started to influence Chinese art during this time. A Jesuit priest named Matteo Ricci brought Western artworks to China. These showed new ways of using perspective and shading.

-

Tang Yin's A Fisher in Autumn

-

Detail of The Emperor's Approach showing the Wanli Emperor's royal carriage being pulled by elephants and escorted by cavalry (full panoramic painting here)

Early Qing Dynasty Painting: Tradition and Innovation

Early Qing dynasty painting had two main styles: the Orthodox school and the Individualist painters. Both followed the ideas of Dong Qichang, but in different ways.

The "Four Wangs" (like Wang Jian and Wang Shimin) were famous in the Orthodox school. They tried to recreate old styles, focusing on the brushwork and calligraphy of ancient masters. The younger Wang Yuanqi (1642–1715) often wrote notes on his paintings explaining how they related to older works.

The Individualist painters included Bada Shanren (1626–1705) and Shitao (1641–1707). They wanted to go beyond tradition and create their own unique styles. In this way, they were actually following Dong Qichang's ideas more closely than the official Orthodox school.

Artists who weren't scholars or aristocrats also became famous. Some created paintings to sell, like Ma Quan (late 17th–18th century), who painted common flowers, birds, and insects. These artists were still skilled in art. Ma Quan, for example, based her brushwork on Song dynasty examples. The "boneless technique" (Chinese: 沒骨畫), which used colors without outlines, was continued by painters like Yun Shouping (1633–1690).

As color printing improved, art instruction books were published. The Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden), first published in 1679, has been a textbook for artists ever since.

-

The Yongzheng Emperor Enjoying Himself During the 8th Lunar Month, by anonymous court artists, 1723–1735 AD, Palace Museum, Beijing, showing the use of linear perspective.

-

Album Leaf, Yun Bing, 17th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, showing the "boneless" technique.

Late Qing Dynasty Art: New Forms and Schools

Nianhua were colored woodblock prints used for decoration during the Chinese New Year. In the 19th century, they also became a way to share news.

The Shanghai School was a very important Chinese art movement during the late Qing dynasty and 20th century. Artists from this school helped traditional Chinese art reach new heights. The Shanghai School challenged old art traditions but still respected ancient masters. Its members were educated scholars who questioned the purpose of art as society changed rapidly. Their works were very creative and often included subtle social messages. Famous artists from this school include Ren Xiong, Ren Bonian, and Wu Changshuo.

Chinese Painting Styles

Traditional Chinese painting, like Chinese calligraphy, uses a brush dipped in black or colored ink. Oils are not used. The most popular materials are paper and silk. Finished paintings can be mounted on scrolls, like hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Paintings can also be done on album pages, walls, lacquerware, folding screens, and other surfaces.

The two main techniques in Chinese painting are:

- Gong-bi (工筆), meaning "meticulous." This style uses very detailed brushstrokes and precise outlines. It often has many colors and usually shows people or tells stories. Artists working for the royal court or in workshops often used this style. Bird-and-flower paintings were often done in Gong-bi.

- Ink and wash painting (水墨), also called "literati painting." This was one of the "four arts" of the Chinese scholar-official class. In theory, gentlemen practiced this art. This style is also called "xie yi" (寫意) or freehand style.

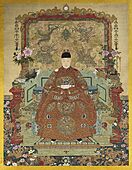

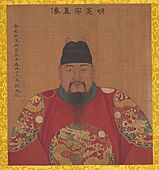

From the Han to Tang dynasties, artists mainly painted human figures. We know about early Chinese figure painting from burial sites, where paintings were kept on silk banners, lacquer objects, and tomb walls. Many early tomb paintings were meant to protect the dead or help their souls reach paradise. Others showed the teachings of the philosopher Confucius or scenes of daily life. Most Chinese portraits showed a formal, full-length view from the front. They were used by families to honor their ancestors.

Many art experts believe landscape painting is the highest form of Chinese painting. The period from the Five Dynasties to the Northern Song (907–1127) is called the "Great age of Chinese landscape." In the north, artists like Jing Hao and Fan Kuan painted tall mountains using strong black lines and ink washes to show rough rocks. In the south, Dong Yuan and Juran painted the rolling hills and rivers of their homeland in peaceful scenes with softer brushwork. These two styles became the classic forms of Chinese landscape painting.

-

Early Autumn; by Qian Xuan; 13th century; ink and colors on paper scroll; 26.7 × 120.7 cm; Detroit Institute of Arts. The decaying lotus leaves and dragonflies hovering over stagnant water are probably a veiled criticism of Mongol rule

-

Lohan manifesting himself as an eleven-headed Guanyin; circa 1178; ink and color on silk; 111.5 × 53.1 cm; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Wang Xizhi watching geese; by Qian Xuan; 1235 – before 1307; handscroll (ink, color and gold on paper); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

The eight hosts of Deva, Naga and Yakshi; 1454; hanging scroll, ink and color on silk; dimensions of the painting: 140.2 × 78.8 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Portrait of Zhu Youjiao; after 1620; painting; National Palace Museum, Taipei

-

Court Ladies of the Former Shu by Tang Yin

-

Brooklyn Museum – The Chinese Buddhist Pilgrim Xuanzang

Sculpture: From Bronzes to Buddhas

Chinese ritual bronzes from the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties (starting around 1500 BC) have greatly influenced Chinese art. These bronzes have complex patterns and animal decorations, but they usually don't show human figures. This is different from the huge human figures recently found at Sanxingdui.

The amazing Terracotta Army was made for the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a united China (221 to 210 BC). It was a grand version of the figures that had been placed in tombs for a long time. These figures were meant to let the dead enjoy the same lifestyle in the afterlife as they did when alive, replacing earlier human sacrifices. Smaller figures made of pottery or wood were placed in tombs for many centuries after, reaching their best quality in the Tang dynasty tomb figures.

Traditional Chinese religions usually don't use statues of gods. So, most large religious sculptures in China are Buddhist. They date from the 4th to the 14th century and were first influenced by Greco-Buddhist art that came through the Silk Road. Buddhism also led to large portrait sculptures. Imperial tombs have impressive paths lined with real and mythical animals, similar in scale to those in Egypt. Smaller versions decorate temples and palaces. Small Buddhist figures and groups were made with great skill from various materials, as were detailed decorations on objects, especially in metalwork and jade. Sculptors were seen as craftspeople, and very few of their names are known.

-

Ritual tripod cauldron (ding); circa 13th century BC; bronze: height with handles: 25.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Wine vase (zun); 13th century BCE; bronze inlaid with black pigment; height: 40 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

One of the warriors of the Terracotta Army, a famous collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China

-

The Flying Horse of Gansu; circa 300; bronze; height: 34.5 cm, length: 45 cm; width: 13.1 cm; Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou

-

Votive stele with Buddha Shakyamuni; dated 542 (Eastern Wei dynasty); limestone; Museum Rietberg (Zürich, Switzerland)

-

The Leshan Giant Buddha, a 71 m tall stone statue, built between 713 and 803, Tang dynasty

-

Seated luohan; 18th–19th century; lapis lazuli; height: 18.1 cm, width: 25.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ceramics: The Art of Pottery

Chinese ceramic ware has been developing continuously since ancient times and is one of the most important forms of Chinese art. China has many natural materials needed to make ceramics. The first types of ceramics were made during the Stone Age. Later, they ranged from building materials like bricks and tiles, to handmade pottery, to the very fancy Chinese porcelain made for the emperor. Most later Chinese ceramics, even the best ones, were made in large factories. So, we don't know the names of many individual potters or painters. Many famous workshops were owned by the Emperor. Large amounts of ceramics were also sent abroad as gifts or for trade very early on.

-

Tomb guardian; early 700s; glazed earthenware, sancai (three-color) ware; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

The David Vases; 1351 (the Yuan dynasty); porcelain, cobalt blue decor under glaze; height: 63.8 cm; British Museum (London)

-

Jar: 18th century; porcelain painted in overglaze famille rose enamels; height: 61 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

early Yaozhou ware from the Five Dynasties period, 10th Century AD

-

Chinese Porcelain Guanyin, 17th–18th century

-

12th century; from the southern Song dynasty.

Decorative Arts: Beauty in Everyday Objects

Besides porcelain, many other valuable materials were skillfully worked and decorated. These were used for various purposes or just for display. Chinese jade was believed to have magical powers. In the Stone and Bronze Ages, it was used for large, ceremonial versions of weapons and tools, as well as for bi disks and cong vessels. Later, many objects and small sculptures were carved from jade, which was a difficult and slow process.

Bronze, gold, silver, rhinoceros horn, Chinese silk, ivory, lacquer, carved lacquer, cloisonne enamel, and many other materials had special artists working with them. Cloisonne, a type of enamel work, developed in interesting ways in China.

Folding screens (Chinese: 屏風; pinyin: píngfēng) were often decorated with beautiful art. Common themes included mythology, palace scenes, and nature. They were made from materials like wood, paper, and silk. Folding screens were perfect for displaying paintings and calligraphy. Many artists painted on paper or silk and then attached it to the screens.

-

Covered box with pavilion and figures; 1300s (the Yuan dynasty); carved lacquer; Tokyo National Museum

-

Chinese low-back armchair; late 16th–18th century (late Ming dynasty to Qing dynasty); huanghuali rosewood; Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington D.C.

-

Cup; early 17th century; rhinoceros horn; height: 10.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Folding screen; circa 1690; lacquered wood and paper; Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon

-

Chinese moon-gate bed; circa 1876; satinwood (huang lu), other Asian woods and ivory; Peabody Essex Museum (Salem, Massachusetts)

Architecture: Building with Tradition

Chinese architecture refers to a building style that has developed in East Asia over many centuries. It has greatly influenced the architecture of Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. The basic rules of Chinese architecture have stayed mostly the same, with changes mainly in the decorations.

From ancient times, people built strong walls from packed earth and used wooden frames for buildings. The ruins of a palace from the Shang dynasty have been found underground. In traditional China, buildings focused on being wide and horizontal. They had heavy platforms and large roofs that seemed to float above the base. The vertical walls were not as important. This is different from Western architecture, which often focuses on height.

An exception to this rule is the Chinese tower, or pagoda. These towers started as a local tradition and were later influenced by Buddhist stupas from Nepal, which were used to house religious texts. Ancient Chinese tombs show models of multi-story residential towers and watchtowers from the Han dynasty. The oldest existing Buddhist Chinese pagoda is the Songyue Pagoda, a 40-meter (131 ft) tall brick tower built in 523 CE.

From the 6th century onwards, stone buildings became more common. The oldest stone and brick arches are found in Han dynasty tombs. The Zhaozhou Bridge, built from 595 to 605 CE, is China's oldest existing stone bridge and the world's oldest fully stone arch bridge with open spandrels.

In old China, architects and builders were not as highly respected as government officials. Much of the knowledge about early Chinese architecture was passed down from father to son or from teacher to apprentice. However, there were some early books about Chinese architecture. The most important one is the Yingzao Fashi, a building manual written around 1100 and published in 1103. It has many detailed pictures and diagrams showing how to build halls and other parts of buildings.

Certain architectural features were only allowed for buildings made for the Emperor. For example, yellow roof tiles were used because yellow was the Imperial color. You can still see yellow roof tiles on most buildings in the Forbidden City. However, the Temple of Heaven uses blue roof tiles to represent the sky. The roofs are almost always supported by special brackets. The wooden columns and walls of buildings are often red.

Today, many Chinese buildings use modern and Western styles.

-

Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, the main building of the Temple of Heaven (Beijing), 1703–1790

-

The Longxing Temple in Hebei (Zhengding, China), 1052

-

Pagoda of Fogong Temple, Shanxi, 1056

-

The Dacheng Hall of the Temple of Confucius Qufu, Shandong, 1499

Chinoiserie: European Take on Chinese Style

Chinoiserie is how Europeans copied and interpreted Chinese and East Asian art. You can see it in decorative arts, garden design, architecture, and even music. This style became popular in the 18th century because of increased trade with China and East Asia.

Chinoiserie is similar to the rococo style. Both styles use lots of decoration, uneven shapes, and focus on materials and stylized nature. Chinoiserie often shows subjects that Europeans at the time thought were typical of Chinese culture.

-

The Chinese House, a chinoiserie garden pavilion in Sanssouci Park, from Potsdam, Germany

-

Kneehole writing table; circa 1760; mahogany, mahogany veneer and gilt bronze; 88.9 × 97.8 × 62.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Ornamental Design from "Nouvelle suite de cahiers chinois a l'usage des Dessinateurs et des peintres"; after 1775; etching with colored inks à la poupé on off-white laid paper; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (New York City)

-

The Tea House at Myasnitskaya Street in Moscow (Russia)

Modern Chinese Art: New Beginnings

New China Art (1912–1949)

The Modern Art Movement

The effort to modernize Chinese art began in the late Qing dynasty. Traditional art forms started to lose their appeal as society changed. Artists wanted to express new ideas about the world. They explored two main paths: one was to learn from the past to improve the present, and the other was to "learn new methods" from other countries.

Learning from the Past

The art made for the social elite wasn't appealing to the growing middle class. Artists like Wu Changshuo (1844–1927) in Shanghai started painting flowers and plants. His paintings used bold colors and strong brush strokes, making them easier for everyone to enjoy. Qi Baishi (1864–1957) painted things like crabs and shrimps, which were even more relatable to common people.

Huang Binhong (1865–1955) criticized the old literati paintings and created his own landscape style by studying Chinese art history. Zhang Daqian (1899–1983) used wall paintings from the Dunhuang caves to help him move beyond traditional literati art.

Learning New Methods

The Lingnan School (岭南画派) borrowed some ideas from Western art for their ink paintings. Gao Jianfu (1879–1951), one of the founders, wanted to use his paintings to highlight national issues and bring positive change to society.

A bigger change in style started with Kang Youwei (1858–1927), a reformer who liked the more realistic art of the Song dynasty. He believed Chinese art could be refreshed by using realistic European art techniques. Xu Beihong (1895–1953) took this idea seriously and went to Paris to learn these skills. Liu Haisu (1896–1994) went to Japan for Western techniques. Both Xu and Liu became presidents of important art schools, teaching new ideas and skills to young artists.

Cai Yuanpei (1868–1940) was a leader in the "New Culture Movement". Those involved believed that intellectual activities should benefit everyone, not just the elite. Cai's idea that art could help society was adopted by Lin Fengmian (1900–1991).

Together with Yan Wenliang (1893–1988), Xu, Liu, and Lin were known as the "Four Great Academy Presidents." They led the national modern art movement. However, wars and civil unrest prevented this movement from fully growing. After the war, Chinese modern art developed differently in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and overseas.

Postwar Chinese Art (1949–1976)

This period covers from 1949, when the Chinese civil war ended, to 1976, when mainland China opened up more to the outside world.

Mainland China: Art for a Purpose

The postwar era in mainland China can be divided into "The 17 Years" (1949 to 1966) and the "Cultural Revolution" (1966 to 1976).

The 17 Years

Chinese artists adopted social realism, which combined revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism. Art was not valued for its own sake but was used for political purposes. According to Mao Zedong, art should be a "powerful weapon for uniting and educating the people." Praising political leaders and celebrating socialist achievements became the main themes. Western art styles like Cubism and Abstraction were seen as superficial.

The Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957 greatly harmed artists. Those labeled as "rightists" lost their right to create art and even their jobs. Their social standing and that of their families suffered greatly.

Some important paintings from this time include:

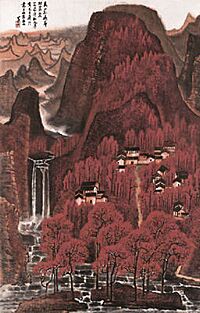

- Li Keran, Reddening of Ten Thousand Mountains

- Huang Wei, The Snowstorm

- Dong Xiwen, The Founding Ceremony of the Nation was changed several times due to political shifts.

The Cultural Revolution

These ten years (1966-1976) are also called the "Ten Years of Calamity." To destroy old social order, countless temples, historic sites, artworks, and books were ruined or burned. During this time, portraits of Mao and propaganda posters were everywhere. Anything even slightly out of line was destroyed, and the person behind it was punished. For example, a painting of an owl with one eye open and one closed was seen as a sign of unhappiness. Many famous artists were persecuted. The "Four Great Academy Presidents" (except Xu, who had passed away) were all jailed, and their work was destroyed.

Despite these difficulties, some notable paintings were created:

- Chen Yifei, The Yellow River

- Sun Jingbo, New Song by Ah Xi

Hong Kong: Blending East and West

Hong Kong was a British colony until 1997. Local art groups were mostly run by Westerners until many Chinese artists moved there during the Sino-Japanese War. New art colleges were started after the war. Local artists began holding shows in the early 1960s. After a period of moving away from traditional Western art, some artists started creating experimental works that combined both Western and Eastern techniques. Then came a call to return to Chinese traditional art and create unique Hong Kong art forms. Lui Shou-Kwan led this trend, adding Western ideas to his Chinese ink paintings.

- Lui Shou Kwan, 1965

Chinese Artists Overseas

Paris

Many Chinese artists went to Paris in the early 1900s to study Western art, such as Lin Fengmian and Wu Guanzhong. Most of them returned to China before 1949 and became leaders in the modern art movement. Some artists, like Sanyu and Pan Yuliang, stayed in Paris because of its rich international art scene. Their paintings often had a mix of Chinese and Western elements. These artists not only influenced Chinese modern art but also introduced modern Eastern art to Parisians.

- Zao Wou-Ki, 1959

United States

Li Tiefu (1869–1952) was a skilled oil painter who studied in Canada and the United States. He was active in the revolutionary movement led by Sun Yat-sen.

Zeng Youhe (1925–2017) was born in Beijing and gained international recognition for her work. She moved to Honolulu in 1949. Her paintings were abstract but still had a touch of traditional Chinese ink painting.

- Zeng Youhe, 1961

Taiwan

Traditional Chinese art didn't have strong roots in Taiwan. Art forms there were mostly decorative until young people who grew up under Japanese rule received formal art education in Japan. Not held back by old traditions, they explored "learning new methods." When Nationalists arrived in Taiwan, a group of ambitious young artists continued the modern art movement. The most notable groups were the Fifth Moon Group and the Ton-Fan Art Group.

Fifth Moon Group

The original members of this group were art students. They wanted to show that creating new art was valuable, even if it didn't directly help art teaching. Later, it became a movement to modernize Chinese art.

The Fifth Moon Group studied Western art and decided that abstract art was the best way for modern Chinese art to express itself. They believed that the best Chinese paintings didn't need to show realistic objects. Instead, they focused on atmosphere and "vividness" from brush strokes and how ink interacted with paper. They felt that the beauty of a painting could be seen directly from its shapes, textures, and colors, without needing to represent real things.

The group was active from 1957 to 1972. Key members included Liu Guosong and Fong Chung-ray.

Ton-Fan Art Group

The members of this group were students of Li Zhongsheng, an artist who was active in the modern art movement. He and other artists introduced modern art to Taiwan through magazines and articles. His teaching style was unique and encouraged students to think for themselves.

The group's goal was to introduce modern art to the public. They believed there should be no limits on the form or style of a modern Chinese painting, as long as it expressed a Chinese meaning. The group was active from 1957 to 1971.

Contemporary Chinese Art (Mid-1980s – 1990s and Beyond)

Modern Expressions

Contemporary Chinese art, also called Chinese avant-garde art, has continued to grow since the 1980s, after the Cultural Revolution. This art includes painting, film, video, photography, and performance art.

In the past, art shows that were seen as controversial were often shut down by the police. Performance artists especially faced the risk of arrest in the early 1990s. More recently, the Chinese government has been more accepting. However, many internationally famous artists are still limited in how much media attention they get at home, or their exhibitions might be ordered to close. Some leading contemporary visual artists include Ai Weiwei, Cai Guoqiang, and Zhang Xiaogang.

Visual Art: New Voices

Starting in the late 1980s, younger Chinese visual artists gained more exposure in the West, partly through curators outside China. Curators and critics within China also helped promote certain types of painting. They spread the idea that art could be a strong social force in Chinese culture. There was some debate because critics felt that these ideas about contemporary Chinese art were sometimes based on personal preferences, which could make it harder for many avant-garde artists to connect with Chinese officials and Western art buyers.

The Art Market: A Growing Global Presence

Today, the market for Chinese art, both old and new, is growing very fast around the world. In 2006, the Voice of America reported that modern Chinese art was selling for record prices both internationally and in China. Some experts even worried that the market might be getting too hot.

In 2011, China became the world's second-largest market for art and antiques, making up 23 percent of the total art market. This was just behind the United States. A big change driving this growth is that new wealthy buyers from countries once considered poor often prefer non-Western art. For example, a large art gallery has offices in New York and Beijing, but its clients mainly come from Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East.

One area that has become a center for art and business is the 798 Art District in Beijing. In 2006, the artist Zhang Xiaogang sold a 1993 painting for US$2.3 million. This painting showed blank-faced Chinese families from the Cultural Revolution era. In 2007, Yue Minjun's work Execution sold for a record nearly $6 million at Sotheby's.

Other artworks have been sold at places like Christie's. A Chinese porcelain piece with the mark of the Qianlong Emperor sold for HKD $151.3 million. Sotheby's and Christie's are major places where classic Chinese porcelain art is sold, including pieces from the Ming dynasty. The International Herald Tribune reported that Chinese porcelains were highly sought after in the art market.

A 1964 painting by Li Keran called "All the Mountains Blanketed in Red" sold for HKD $35 million. Auctions also took place at Sotheby's where Xu Beihong's 1939 masterpiece "Put Down Your Whip" sold for HKD $72 million. The art market isn't just for fine arts; many other types of contemporary pieces are also sold.

Where to See Chinese Art

- National Art Museum of China (Beijing)

- Palace Museum (Forbidden City, Beijing)

- China Art Museum (Shanghai)

- Power Station of Art (Shanghai)

- National Palace Museum (Taipei, Taiwan)

See also

- 798 Art Zone

- Chinese fine art

- Chinese jade

- Chinese papercut

- Chinese folk art

- Eastern art history

- History of China

- List of Chinese women artists

- Fruit pit carving

- Tian-tsui

- Jue

- Jian

- Oil paper umbrella

- Wuxia

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |