Scholar-official facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Scholar-official |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

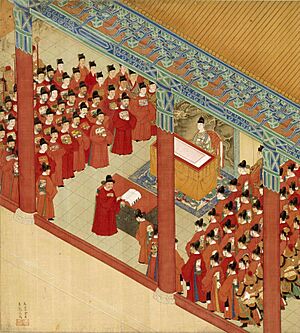

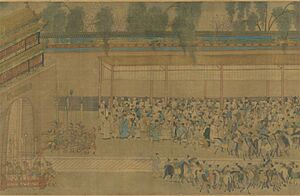

Painting that depicts the career of a civil servant. The career path starts with passing the civil service examinations (left side) and progresses to a high position in the government (right side).

|

|||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 士大夫 | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Sĩ đại phu | ||||||

| Chữ Hán | 士大夫 | ||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 사대부 | ||||||

| Hanja | 士大夫 | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 士大夫 | ||||||

| Hiragana | したいふ | ||||||

|

|||||||

The scholar-officials, also known as literati or scholar-gentlemen (Chinese: 士大夫; pinyin: shì dàfū), were important government officials and respected scholars in Chinese society. They formed a special social group.

These scholar-officials were politicians and government workers chosen by the emperor of China. They handled the daily tasks of running the country. This system lasted from the Han dynasty until the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912. The Qing dynasty was China's last imperial ruling family. After the Sui dynasty, most of these officials came from wealthy families called the scholar-gentry (紳士 shēnshì). They earned special academic degrees by passing difficult imperial examinations.

Scholar-officials were the top class in imperial China. They were very educated, especially in literature and arts. This included skills like calligraphy (beautiful writing) and studying Confucian texts. They controlled the government and local life in China until the early 1900s.

Contents

How Did Scholar-Officials Start?

What Were Shi and Da Fu?

The idea of "scholar-official" as a social group began during the Warring States period. Before this time, Shi and Da Fu were two different classes. During the Western Zhou dynasty, society was divided into groups. These included the king, lords, Da Fu, Shi, ordinary people, and slaves.

Da Fu were from noble families and served as high-ranking officers. Shi were a class between Da Fu and common people. They could only be low-level officials. During the Warring States period, states fought many wars. Governments also started to use more officials. Many talented people from the Shi class helped their lords a lot. The Shi became more important. Da Fu slowly became a government job, not a family title passed down. Eventually, the Shi and Da Fu groups joined together to become the scholar-officials (士大夫 Shi Da Fu).

Ancient China's Social Structure

China's old feudal society divided common people into four main groups. Scholar-officials were at the very top of this structure. This system helped scholar-officials become strong and important. The order of these Four Occupations was: scholar-officials, farmers, artisans (skilled workers), and merchants.

How Confucianism Shaped Scholar-Officials

- Further information: Junzi and Four arts

Confucianism was a main part of traditional Chinese culture. It was also the main idea behind the emperor's rule. Confucian ideas became very popular in Chinese society. Education based on Confucianism was used to choose officials for most government jobs.

Confucianism taught about order and respect. But it also said that scholar-officials and ministers were not just servants of the ruler. They had an important role in keeping society stable. This meant they could even disagree with the ruler. They could oppose him if he was not fair or did not help his people. Ideally, power was shared between the wise Confucian scholars and the emperors. A ruler should keep power with the support of his ministers. These ministers had the right to remove a bad ruler.

During the Song and Ming dynasties, Confucian thinkers added ideas from Taoist and Buddhist beliefs. This created a new way of thinking called Neo-Confucianism. This made the scholar-official class even stronger. It also helped create a special moral code for scholar-officials. This code greatly influenced Chinese scholars for many years.

How Officials Were Chosen in Ancient China

The ways officials were chosen in ancient China were key to forming the scholar-official class.

- Recommendatory System: People were recommended for jobs.

- Nine-rank system: Officials were ranked into nine levels.

- Imperial examination: People took tests to get jobs.

The Rise of Scholar-Officials

Han to Northern and Southern Dynasties (202 BC—589 AD)

During this long period, officials were often chosen using the Recommendatory System and Nine-rank System. Scholar-officials usually came from powerful families. These included clans like the Zheng clan of Xingyang and the Wang clan of Langya. These families were known for having Confucian scholars and high-ranking officials for many generations. Some families even had several chancellors (prime ministers).

They built strong connections by marrying into other powerful families or the imperial family. This also meant they had a lot of control over education and government jobs.

Sui and Tang Dynasties (581—907)

The Civil Service Examination was officially started in 587 AD. This test allowed people to become scholar-officials. Starting with the Sui dynasty, those from the right family background who passed this exam could become officials. In the early Tang dynasty, Empress Wu Zetian improved the Imperial Examination system. She created the Metropolitan exam. People who passed this were called Jinshi (the highest degree). Those who passed the Provincial Exam were called Juren.

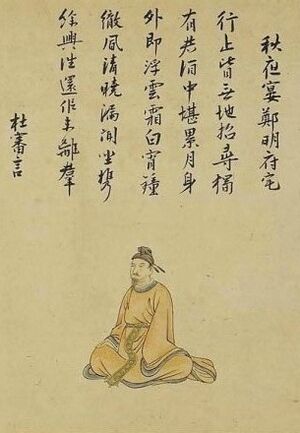

Empress Wu's changes slowly led to the modern idea of scholar-officials. The government chose scholar-officials by looking at their poems and essays. They checked their knowledge of Confucian and some Buddhist texts. Educated people who passed the exam became officials. Many famous Tang poets, like Du Mu, were scholar-officials.

During the Tang Dynasty, the meaning of "scholar-officials" was still changing. Some texts said that scholars who passed the exam but didn't get an official job were just Shi. Other texts said that any scholar, whether they had a job or not, could be called a scholar-official.

Song Dynasty (960-1279)

The Song dynasty was a great time for scholar-officials. By this time, passing the Imperial Examination was the main way to get a government job. The Imperial Examination system kept getting better. The government jobs completely replaced the old noble families. The system of scholar-officials running the government was fully set up.

Song was the only dynasty in Chinese history that gave scholar-officials special legal rights. The first Song emperor, Zhao Kuangyin, greatly respected educated people. Almost all Song emperors showed great respect to scholars. If a scholar-official in the Song dynasty did something wrong, they were not directly put on trial. Instead, an internal review took the place of a formal court process. If their mistake was not serious, they might only get a warning instead of a punishment.

Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties (1271—1912)

During the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, a very strict writing style called the eight-legged essay was used in the Imperial Examination. Scholar-officials from this time could not speak or create as freely. This was because of the strict political environment.

The strong link between the Imperial Examination and getting a government job continued. The whole society believed in the idea of "studying well to become an official" (学而优则仕). In 1905, the Qing government stopped the imperial examination system. This led to the scholar-officials slowly disappearing.

What Else Did Scholar-Officials Do?

Only a few scholar-officials could become high-ranking court or local officials. Most of them stayed in villages or cities and became community leaders. These scholar-gentlemen helped their communities in many ways. They organized social welfare projects and taught in private schools. They also helped solve small legal disagreements. They oversaw community projects and helped keep local order. They led Confucian ceremonies and helped the government collect taxes. They also taught Confucian moral lessons. As a group, these scholars claimed to represent good morals and values.

The county magistrate (the official in charge of a county) was not allowed to serve in his home district. So, he relied on the local gentry for advice and to carry out projects. This gave the gentry power to help themselves and their supporters.

How Were Scholar-Officials Judged?

- Further information: Imperial examinations

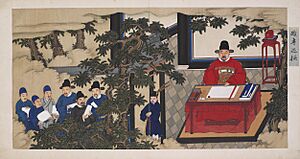

In theory, this system was supposed to create a ruling class based on skill and talent. The best students would run the country. The imperial examinations gave many people a chance to gain political power and respect. This encouraged serious study and formal education. The system did not officially discriminate based on social status. So, it offered a way for people to move up in society.

However, the exam system focused heavily on Confucian literature. This meant the best writers and scholars got high positions. But the system did not have strong rules to prevent officials from using their power unfairly. It only relied on the Confucian moral teachings tested by the exams. Once officials secured their future by passing the exams, they were sometimes tempted to use their power for their own gain.

The Princeton scholar Benjamin Elman wrote that some people criticized the exam system. They said it slowed down China's progress in the last century. But he also said that preparing for the exams trained government officials in a shared culture. He believed that "classical examinations were an effective cultural, social, political, and educational construction that met the needs of the dynastic bureaucracy while simultaneously supporting late imperial social structure."

The Civil Service Examination system also influenced other parts of East Asia. Scholar-officials became important in ancient Korea (including Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje), the Ryukyu Kingdom, and Vietnam.

See also

- Bildungsbürgertum

- Cabang Atas, the Chinese gentry of colonial Indonesia

- County magistrate, the official in charge of the county

- Four arts

- Junzi

- Kuge

- Landed gentry in China

- Mandarin (bureaucrat)

- Yangban, the Korean form of the scholar-official