Four occupations facts for kids

The four occupations (simplified Chinese: 士农工商; traditional Chinese: 士農工商; pinyin: Shì nóng gōng shāng) were a way people in ancient China were grouped by their jobs. This system was used by thinkers like Confucians and Legalists as far back as the late Zhou dynasty (around 1046–256 BC). It was a key part of China's early social structure.

The four groups were:

- The shi (gentry scholars)

- The nong (peasant farmers)

- The gong (artisans and craftspeople)

- The shang (merchants and traders)

It's important to know that these groups weren't always listed in the same order. Also, they weren't like strict social classes where wealth or family background decided your place. People could move between these groups, and your job wasn't usually passed down from your parents. This system was more of an ideal way to see society rather than a strict rule for everyone. Over time, especially during the Song dynasty and Ming dynasty, the lines between these jobs became less clear.

This way of organizing society was also used in other parts of Asia, like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. However, the meaning of the shi (scholar) group often changed in these different cultures.

Contents

How the Four Occupations Began

The idea of grouping common people by their jobs first appeared during the Warring States period (403–221 BC) in China. A historian named Ban Gu (AD 32–92) from the Han dynasty wrote about these four groups. He believed they had existed much earlier, during the Zhou dynasty.

Ban Gu described the groups in this order, from highest to lowest:

- Scholars (shi): People who studied to get important government jobs.

- Farmers (nong): Those who grew food and worked the land.

- Artisans (gong): People who made things with their hands, like tools or crafts.

- Merchants (shang): Those who bought and sold goods.

Other ancient texts sometimes listed the groups in a different order. For example, some placed merchants before farmers. One text even suggested that all four occupations should be seen as equal.

Historians today believe that the "four occupations" were more of a way to talk about society than a strict government rule. However, some laws did treat these groups differently.

The order of the groups was often based on how useful they were thought to be for the state and society. Scholars, who used their minds, were usually first. Farmers, who produced food, were seen as creating wealth and came next. Artisans made useful goods. Merchants were often last because some thought they just moved wealth around or caused prices to change too much.

Below these four groups were the "mean people" (Chinese: 賤民 jiànmín). These were people in jobs considered "humiliating," like entertainers. Unlike in some European systems, the four occupations were not usually passed down from parents to children. In theory, any man could become an official by passing special government exams.

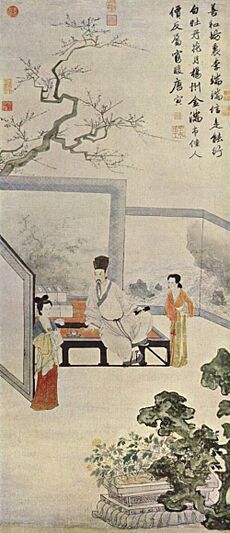

Shī (Scholars)

From Warriors to Scholars

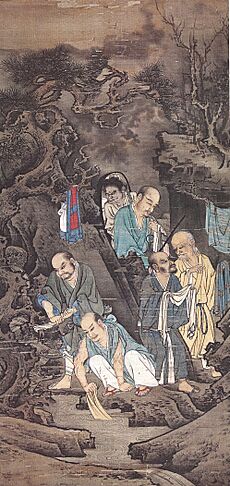

In the very old Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC) and early Zhou dynasties, the shi were like knights. They were from noble families, but not as high-ranking as dukes or marquises. They were known for riding in chariots and leading battles. They also helped with government tasks. These early shi were skilled archers and fighters.

They followed a strict code of honor, similar to chivalry. There are stories of shi warriors stopping a fight to allow an opponent to return a shot.

As time went on, especially during the Warring States period (403–221 BC), fighting styles changed. Mounted soldiers and crossbowmen became more important than chariots. The role of the shi in battle became less important. This was also a time when many new ideas and philosophies appeared in China. People started to value thinking and learning more. So, the shi became known for their knowledge, their ability to manage things, and their strong moral beliefs.

Scholar-Officials and Imperial Exams

Under Duke Xiao of Qin and his minister Shang Yang, the state of Qin changed a lot. They used a philosophy called Legalism, which focused on strict laws and rewarding people for hard work and obedience. This system helped reduce the power of old noble families. It also changed the shi class from warrior-nobles into officials chosen for their skills.

When the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) united China, the emperor put officials in charge instead of nobles. This ended the old feudal system and created a strong, central government. This type of government was used by later dynasties.

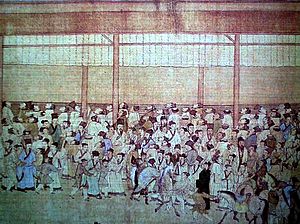

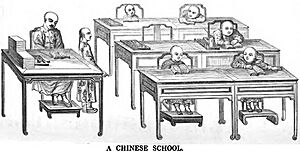

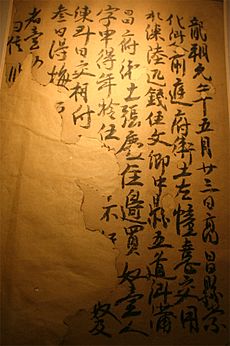

After the Qin dynasty fell, the Han dynasty (202 BC–AD 220) began. In 165 BC, Emperor Wen of Han started using exams to choose government workers. Later, Emperor Wu of Han made Confucianism the main way of thinking for the government. He set up a national school where officials would choose candidates to take exams on Confucian teachings. The emperor would then pick officials from those who passed.

During the Sui dynasty (581–618) and Tang dynasty (618–907), the shi class became more defined by a formal civil service examination system. However, people were still often chosen for jobs based on recommendations. It wasn't until the Song dynasty (960–1279) that passing these exams became the most important way to get a government job. The exams were very competitive, making the shi class less about noble birth and more about being a skilled government worker.

Scholar-officials did more than just work in government. They also helped with public services. They ran schools, public hospitals, and retirement homes. Some scholars were also experts in science, math, music, and government. Others were pioneers in studying old writings and objects.

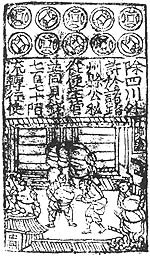

From the 11th to 13th centuries, many more people took the exams. The invention of woodblock printing and movable type helped spread knowledge. This meant more people could study and try for a government job. But there weren't enough jobs for everyone who passed. So, many graduates who didn't get government jobs helped their local communities. They might fund public projects, run private schools, or help collect taxes.

Nóng (Farmers)

Since ancient times, farming has been super important in China. Farmers grew the food that fed everyone. The taxes on their land also provided most of the money for the government. Because of this, farmers were seen as very valuable members of society. Even the families of scholars often owned land and grew crops.

In early China, land was sometimes divided using a system called the well-field system. A square area of land was split into nine parts. Eight parts were farmed by families for themselves. The middle part was farmed by everyone for the noble who owned the land. This system eventually changed to private land ownership.

Later, from AD 485–763, land was given out more equally to farmers based on how many working men were in a family. But as the government's power weakened, land went back into private hands.

During the Song dynasty, farmers also made things like wine, charcoal, paper, and cloth on a small scale.

By the Ming dynasty, the difference between farmers and artisans (craftspeople) started to blur. Farmers might work as artisans during busy times, and artisans might work on farms. The line between city and country also became less clear, as farms were often found just outside or even inside city walls.

Gōng (Artisans)

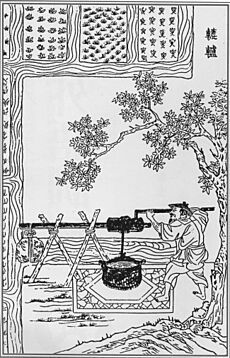

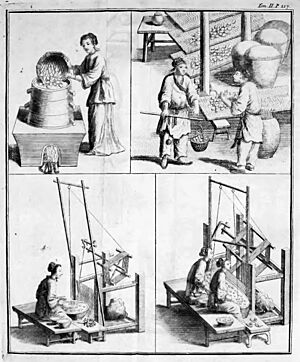

Artisans and craftspeople, whose name means "labor," were like farmers because they made important goods for everyone. They didn't pay as much in land taxes since they often didn't own land. But in theory, they were respected more than merchants. For a long time, their skills were passed down from father to son. Some building knowledge was even written down in books.

Artisans could work for the government or for themselves. A skilled artisan could earn enough money to hire helpers or apprentices. This allowed them to start their own small businesses, selling their own work and that of others. Like merchants, artisans also formed their own groups or guilds.

In later Ming and early Qing dynasties, many workshops started to pay wages to workers. They achieved large-scale production by having many small workshops, each with a small team led by a master craftsman.

Some architects and builders became very famous for their work. For example, the Yingzao Fashi was a building manual printed in 1103. It was written by Li Jie and supported by Emperor Huizong of Song. This book helped government agencies and literate craftspeople across the country.

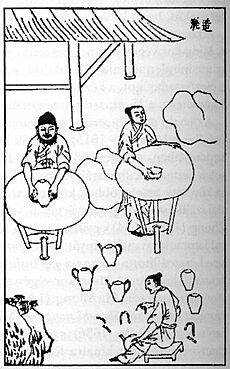

The Ming dynasty was known for its many porcelain kilns, which helped the economy. Later, Qing emperors like the Kangxi Emperor encouraged porcelain exports. Chinese porcelain made for Europe was very popular.

Silk production was also a big industry. Originally, only women worked with silkworms. China kept its lead in silk making by using large-scale production methods, like special looms and mulberry cultivation. Merchant houses would organize silk production, giving silk to households to weave as piece work.

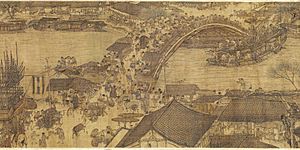

Shāng (Merchants)

In ancient China, before the imperial era, merchants were seen as important for moving essential goods around. Even the legendary Emperor Shun was said to have been a merchant before he became emperor. Old records and artifacts show that merchant activity was highly valued.

In Imperial China, merchants, traders, and peddlers were seen as necessary. However, the scholarly elite often placed them lowest among the four occupations. This was because some scholars thought merchants could gain too much wealth or cause prices to change unfairly.

Despite this, merchants in China were often wealthy and had a lot of influence. The philosopher Xunzi encouraged trade and cooperation. The difference between scholars and merchants was not as strict as in some other countries. Scholars even welcomed merchants if they followed good moral rules. Merchants supported Confucian society by funding education and charities. They also promoted values like honesty and hard work in their businesses. Over time, some scholars even became merchants.

Han dynasty writers mentioned merchants owning huge amounts of land. A very rich merchant could have a fortune worth much more than a middle-class landowner. Some merchant families were as wealthy as the highest government officials. Traveling merchants who traded between cities were often rich because they could avoid being officially registered. They were known to wear fine clothes and ride in fancy carriages.

As Chinese society became more focused on business from the Song dynasty onward, Confucianism slowly started to accept and even support trade. Merchants also used Confucian ideas in their business practices. By the Song period, merchants often worked closely with scholars. The Song government itself became a large business, controlling key industries and monopolies. The government also dealt with merchant guilds, which helped ensure fair prices and wages.

By the late Ming dynasty, officials often needed money from rich merchants. This money was used to build roads, schools, bridges, or to support important industries like book-making. Merchants started to act and dress like scholars to gain more respect. They even bought books that taught them proper behavior and business ethics. The status of merchants rose so much that many scholars proudly wrote in their family histories that they had merchant relatives. The government even gave merchants special licenses, like for trading salt, in exchange for grain shipments to soldiers. This showed that the government realized merchants could help boost state revenues.

Merchants formed groups called huiguan or gongsuo to share risks and make it easier to do business. They also created different types of business partnerships. Merchants often invested their profits in large amounts of land.

Other Social Groups

Many social groups were not included in the four main categories. These included soldiers, religious leaders, eunuchs, concubines, entertainers, servants, and slaves. People in jobs considered "worthless" or "filthy" were called "mean people" (賤人). They had fewer legal rights.

The Emperor and Royal Family

The Emperor of China was at the very top of society. He was believed to have a "Mandate of Heaven," meaning he had a divine right to rule. If an emperor was overthrown, it was seen as a sign that he had lost this mandate. This often led to revolts after major disasters.

The Mandate of Heaven didn't require someone to be born noble. For example, the Han dynasty and Ming dynasty were started by men from common backgrounds.

While the emperor's family was respected, they didn't always have the same power as the emperor himself. In some dynasties, royal family members were given control over small states. But later, their power was limited, and they sometimes even had to take exams to get government jobs, just like commoners.

Eunuchs

Court eunuchs, who served the royal family, were often viewed with suspicion by scholar-officials. This was because some powerful eunuchs managed to control the emperor and the government. Eunuchs at the Forbidden City were known for corruption and stealing. The job offered so many chances for wealth that many men chose to become eunuchs. Some historians believe that eunuchs represented the emperor's personal wishes, while officials represented the government's rules. Their conflicts were often about different ways of running the country.

Religious Workers

In early China, shamans and diviners (people who predicted the future) had some power as religious leaders. But after Emperor Wu of Han made Confucianism the official state belief, rulers became less supportive of shamanism. They didn't want religious leaders to become too powerful.

Fortune-tellers like geomancers (who read land features) and astrologers (who read stars) were not highly respected.

Buddhist monks became very popular from the fourth century. Many poor farmers joined monasteries because monks didn't have to pay taxes. This led to several times when Buddhism was persecuted in China. One reason was that monasteries didn't pay taxes. Also, later Confucian scholars saw Buddhism as a foreign idea that threatened China's moral order.

However, Buddhist monks were often supported by rich people and even Confucian scholars. Monasteries were sometimes grander than a prince's house. Even though rulers supported Buddhism, the government exams still focused on Confucian teachings because they were needed for political and legal matters.

Military

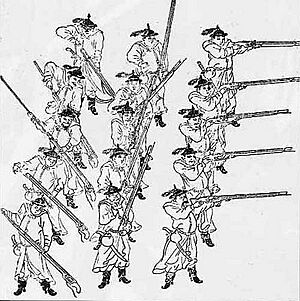

Soldiers were not included in the four main social groups. Scholars, who valued learning and peace, generally disliked violence. By leaving soldiers out of the main social hierarchy, they kept them in a less recognized position.

Soldiers were not highly respected, especially from the Song dynasty onward. This was due to a policy that favored civil officials over military personnel. Soldiers often came from farming families or were debtors trying to escape problems. While peasants were encouraged to join local militias, full-time soldiers were often hired from former bandits or wanderers.

From the 2nd century BC, the government encouraged soldiers on China's borders to settle down and farm. This helped the military feed itself. Several dynasties tried to create a system where military service was passed down through families. But these plans often failed because many soldiers deserted due to the low respect for military jobs. Armies then had to rely on hired fighters or peasant militias.

However, for those without formal education, joining the military was often the fastest way to gain power and rise in society. Even though scholars might look down on soldiers, successful military officers could earn a lot of respect. And despite their dislike for violence, scholar-officials often led troops and held military power themselves.

Entertainers

Entertaining was seen as not very useful to society. It was usually done by the "mean people" (Chinese: 賤民), who were at the bottom of the social ladder.

Entertainers and court performers often depended on wealthy people or worked in city entertainment areas. Full-time musicians had low social status. Giving them official recognition would have given them more prestige.

While "proper" music was seen as important for good character and government, popular music was criticized for being "irregular" and possibly bad for listeners. Still, Chinese society admired many musicians, including women. Musical talent was often a good quality for marriage. During the Ming dynasty, female musicians even played for imperial ceremonies.

Wealthy families often had their own private theater groups. Professional dancers also had low social status, and many became dancers because of poverty. However, some, like Zhao Feiyan, became important by becoming concubines.

The imperial court had special groups to train and manage music and dance performances. Emperors even set up academies for musicians, dancers, and actors.

Professional artists also had low social status.

Slaves

Slavery was not as common in China as in some other parts of the world, but it did exist. It was often a punishment for crimes. In the Han and Tang dynasties, it was illegal to trade Chinese people as slaves (unless they were criminals), but foreign slaves were allowed. Some emperors tried to ban slavery completely, but they were not successful. Sometimes, poor families illegally sold their children into slavery under the guise of adoption.

During some periods, like the Tang dynasty, there were also other groups of "mean people" who were not fully slaves but had limited rights. These included musicians for imperial rituals, general servants, and various types of government or private bondsmen and slaves. They performed many different jobs in homes, on farms, or as guards.

Other Regions

The idea of the four occupations also spread to other East Asian societies influenced by China, like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

Japan

In Japan, the shi role became a hereditary class known as the samurai. Unlike Chinese scholars, samurai were born into their position, and marriage between different classes was not accepted. The samurai were originally warriors but became civil administrators during the Tokugawa shogunate. They made up about 5% of the population.

Older ideas suggested a strict order of "samurai, peasants, craftsmen, and merchants." However, more recent studies show that peasants, craftsmen, and merchants were considered equal social classifications, not a strict hierarchy.

In the 16th century, powerful lords started to centralize their rule. They encouraged artisans and merchants to move into castle towns. This was a time of more social movement, with some merchants even becoming samurai. By the 18th century, samurai and merchants became closely linked, even though samurai often blamed merchants for their financial problems.

Korea

In Silla Korea, scholar-officials were part of strict hereditary classes. Their power was limited by the royal family. Later, a new system was introduced, and King Gwangjong of Goryeo started a civil service exam system in 958. However, only nobles could take these exams, and sons of high-ranking officials were often exempt.

In Joseon Korea, the scholar group was the noble yangban class. They often prevented lower classes from taking advanced exams to keep control of government jobs. Below them were the chungin, who were privileged commoners like scribes and specialists. The yangban made up about 10% of the population.

Vietnam

Vietnamese dynasties also used an exam system to choose scholars for government jobs. Government workers were divided into grades and ministries, and exams were held regularly. The political elite were educated landowners. While all land technically belonged to the ruler, government officials often took over land and leased it to farmers. It was difficult for common people to become high-ranking officials because they usually didn't have access to classical education.

Southeast Asia

Chinese official positions also existed in pre-colonial states in Southeast Asia, like the Sultanates of Malacca and Banten, and the Kingdom of Siam. When European colonial powers arrived, these positions became part of the civil service in Portuguese, Dutch, and British colonies. These Chinese officers had legal and political power over local Chinese communities.

Wealthy Chinese merchant families in British Malaya and the Dutch Indies often donated money to China. In return, they received honorary official ranks from the Imperial Court. These wealthy individuals would dress and act like scholar-officials. They were listed as such in Chinese newspapers and given high status at social events.

In colonial Indonesia, the Dutch government appointed Chinese officers (Majoor, Kapitein, or Luitenant der Chinezen). These officers, usually from wealthy Chinese families, acted like scholar-officials and were seen as leaders of the Confucian social order.

Chinese merchant and labor groups also formed "Kongsi" Federations in Southeast Asia. These were associations of Chinese settlers governed by direct democracy. On the island of Kalimantan, they even established independent states, like the Lanfang Republic, which fought against Dutch colonization.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |