Emperor Wu of Han facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Emperor Wu of Han漢武帝 |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Han dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 9 March 141 BC – 29 March 87 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Jing | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Emperor Zhao | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | 156 BC Chang'an, Han Dynasty |

||||||||||||||||

| Died | 29 March 87 BC (aged 69) Chang'an, Han Dynasty |

||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Maoling, Xianyang, Shaanxi Province | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts | Empress Chen Empress Xiaowusi Consort Wang Lady Li Lady Gouyi at least one other wife |

||||||||||||||||

| Issue | Liu Ju (劉據), Crown Prince Wei Liu Hong (劉閎), Prince of Qi Liu Dan (劉旦), Prince of Yan Liu Xu (劉胥), Prince of Guangling Liu Bo (劉髆), Prince of Changyi Liu Fuling (劉弗陵), Emperor Zhao of Han Eldest Princess Wei Princess Zhuyi Princess Shiyi Princess Eyi Princess Yi'an |

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Western Han | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Emperor Jing | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xiaojing | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Wu of Han | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 漢武帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉武帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The Martial Emperor of Han" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 劉徹 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 刘彻 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (personal name) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Emperor Wu of Han (born Liu Che, 156 – 29 March 87 BC) was a very important ruler of ancient China. He was the seventh emperor of the Han dynasty, ruling for 54 years from 141 to 87 BC. This was the longest reign for a Han Chinese emperor until much later.

During his time, the Han Empire grew much bigger. Its borders stretched far, from Central Asia in the west to northern Korea in the east, and down to northern Vietnam in the south. Emperor Wu also made the government stronger and promoted new ideas for how the country should be run, mixing different philosophies. He also supported arts like poetry and music, making the Imperial Music Bureau very important. His reign also led to more connections between China and lands to its west.

Emperor Wu is seen as one of the greatest emperors in Chinese history. His strong leadership made the Han dynasty a very powerful nation in the world. He made Confucianism the main way of thinking for the government. He also started a school to teach future leaders about Confucian ideas. These changes had a lasting impact on China for many centuries.

Contents

- Understanding Emperor Wu's Names

- Emperor Wu's Early Life

- Becoming Crown Prince

- Early Reign and Challenges

- Gaining Full Power

- Expanding the Empire

- Diplomacy and Exploration

- Religion and Beliefs

- Challenges and Later Years

- Emperor Wu's Lasting Impact

- Poetry and Music

- Era Names During His Reign

- Family Members

- Emperor Wu in Pop Culture

- Images for kids

- See also

Understanding Emperor Wu's Names

Emperor Wu's personal name was Liu Che (劉徹). The "Han" in his name refers to the Han dynasty he was part of. His family name was "Liu," which was the family name of the Han dynasty's founder, Liu Bang.

The word "Di" (帝) means "emperor" in Chinese history. The word "Wu" (武) means "martial" or "warlike." When combined, "Wudi" is his special name given after his death, used for history and religious respect. His temple name, used in ceremonies, was Shizong (世宗).

How Years Were Counted During His Reign

Emperor Wu introduced a new way to count years. He would change the "reign name" every few years, often to celebrate a good event or for good luck. So, a year would be called, for example, the "first year of Jianyuan." This system was used by emperors for a long time after him.

Changing the Calendar

In 104 BC, Emperor Wu introduced a new calendar called the Tai'chu calendar (太初历). Before this, the year started in the tenth month. The new calendar made the first month (正月) the beginning of the new year. This change stuck, and the Chinese calendar has started the year with the first month ever since.

Emperor Wu's Early Life

Liu Che was the 11th son of Liu Qi. His mother, Wang Zhi, had been married before and had a daughter. However, her mother was told by a fortune-teller that both Wang Zhi and her sister would become very important. So, Wang Zhi was divorced and offered to Prince Liu Qi.

Wang Zhi gave birth to Liu Che on the day Liu Qi became Emperor Jing in 156 BC. She claimed she dreamed of a sun falling into her womb, which was seen as a divine sign. Emperor Jing was very happy and made young Liu Che the Prince of Jiaodong. Liu Che was a smart boy and was his father's favorite from a young age.

Becoming Crown Prince

Emperor Jing's first wife, Empress Bo, had no children. So, Emperor Jing's oldest son, Liu Rong, became the crown prince in 153 BC. Liu Rong's mother, Lady Li, was very proud and often got angry with the Emperor. This gave Consort Wang (Liu Che's mother) a chance to gain favor.

Emperor Jing's older sister, Princess Guantao, wanted her daughter, Chen Jiao, to marry Liu Rong. But Lady Li rudely refused. Insulted, Princess Guantao then offered her daughter to Consort Wang's young son, Liu Che, who was only 5 years old. Consort Wang quickly agreed, forming an important alliance.

Princess Guantao's daughter, Chen Jiao, was about eight years older than Liu Che. Emperor Jing was unsure about this age difference. A story says that Princess Guantao held 5-year-old Liu Che and asked if he wanted to marry Chen Jiao. He famously said he would "build a golden house for her" if they married. This convinced Emperor Jing to agree to the marriage. This story led to the Chinese saying "putting Jiao in a golden house" (金屋藏嬌).

Princess Guantao then started to criticize Lady Li to Emperor Jing. Emperor Jing tested Lady Li by asking if she would care for his other children if he died. She refused, making him worried that she would be cruel if her son became emperor. Princess Guantao also praised Liu Che, making Emperor Jing think he was a better choice.

Consort Wang then had a minister suggest that Lady Li be made empress. Emperor Jing, already angry with Lady Li, thought she was plotting with officials. He punished the minister and removed Liu Rong as crown prince in 150 BC. Lady Li lost her titles and died soon after.

Since Empress Bo had been removed earlier, the empress position was open. Emperor Jing made Consort Wang empress. The seven-year-old Liu Che, now the oldest son of the Empress, became crown prince in 149 BC.

In 141 BC, Emperor Jing died, and 15-year-old Liu Che became Emperor Wu. His grandmother became Grand Empress Dowager, and his mother became Empress Dowager. His cousin-wife, Chen Jiao, became Empress Chen.

Early Reign and Challenges

Before Emperor Wu, the Han dynasty focused on economic freedom and less government control. This helped the country recover after a civil war. However, it also meant the central government had less power, and local lords became very strong. Also, the policy of giving gifts to the northern Xiongnu people did not stop their raids.

Emperor Wu, being young and energetic, wanted to change things. In 141 BC, he started big reforms, known as the Jianyuan Reforms. These included:

- Making Confucianism the official way of thinking for the country.

- Asking noblemen to return to their own lands instead of living in the capital and using government money.

- Removing local checkpoints that charged tolls and restricted travel, giving control back to the central government.

- Encouraging people to report illegal activities by nobles.

- Hiring talented commoners for government jobs to reduce the power of the noble class.

However, Emperor Wu's powerful grandmother, Grand Empress Dowager Dou, supported the old ways. She stopped his reforms. Many of his supporters were punished, and some were forced to take their own lives.

Emperor Wu faced plots to remove him. His first wife, Empress Chen, could not have children. His enemies used this to argue he should be replaced. Even his uncle, Tian Fen, sided with his enemies. Emperor Wu's aunt, Princess Guantao, helped him by talking to his grandmother.

Emperor Wu pretended to give up his political plans for a few years. He acted like a normal nobleman, often leaving the capital to hunt and sightsee. This helped him survive until his grandmother's influence lessened.

Gaining Full Power

Emperor Wu knew that the old noble families controlled the government. So, he secretly brought in young, loyal people from ordinary backgrounds. He promoted them to mid-level positions. These new officials, called the "insider court," reported directly to him. They had real power, even if their official ranks were lower. This helped him balance the power of the "outsider court" made up of older, anti-reform officials. He also asked scholars from all over the country to join the government.

In 138 BC, a southern state called Minyue attacked its neighbor, Dong'ou. Dong'ou asked Han for help. Emperor Wu sent an official, Yan Zhu, to gather an army. The Grand Empress Dowager had the special "tiger tally" needed to approve military action. But Yan Zhu found a way around this by forcing a local governor to mobilize the navy. Minyue retreated when they saw the Han forces coming. This was a big win for Emperor Wu. It showed he could act without his grandmother's full approval, giving him more control over the military.

In the same year, Emperor Wu's new favorite, Wei Zifu, became pregnant with his first child. This was very important because it stopped his enemies from using his lack of children as a reason to remove him.

In 135 BC, Grand Empress Dowager Dou died. This removed the last major obstacle to Emperor Wu's reforms. He now had full control of the government.

Expanding the Empire

After his grandmother's death, Emperor Wu began military campaigns to expand the Han Empire. He sent his armies in many directions.

Conquering Southern Lands

Emperor Wu focused on expanding into the south.

Minyue and Dongyue

In 135 BC, Minyue attacked Nanyue. Nanyue asked Han for help. Emperor Wu sent an army. Minyue's nobles, scared of the Han forces, killed their king and sought peace. Minyue was then split into two parts, Minyue and Dongyue, both controlled by Han.

Later, Dongyue, under King Lou Yushan, rebelled against Han. Emperor Wu sent a strong army, which crushed the rebellion. The Dongyue kingdom fell apart, and its king was killed. Both Minyue and Dongyue were then fully added to the Han Empire.

Nanyue

In 111 BC, after a conflict, Emperor Wu sent a large army to conquer Nanyue (which included parts of modern Guangdong, Guangxi, and northern Vietnam). The Han forces captured the capital and added the entire territory to the Han Empire.

Wars Against Northern Nomads

For a long time, there were tensions between China and the northern Xiongnu nomads. The Xiongnu often raided Chinese lands. Earlier Han emperors had tried to keep peace by offering gifts. But the raids continued. After his grandmother died, Emperor Wu decided the Han dynasty was strong enough for a full-scale war.

He ended the peace policy in 133 BC with the Battle of Mayi. This was a failed plan to trap 30,000 Xiongnu soldiers. After this, the Xiongnu increased their attacks. Emperor Wu then changed the Han army's strategy. Instead of chariots and infantry, he focused on mobile cavalry-against-cavalry warfare.

Between 127 and 119 BC, Han generals Wei Qing and Huo Qubing led several victories against the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu were pushed out of important areas like the Ordos Desert. These wins opened up the Northern Silk Road, allowing trade with Central Asia. This also brought new, high-quality horses to the Han army. Emperor Wu then built forts and settled many Chinese soldiers in these new territories.

The Battle of Mobei (119 BC) saw Han forces invade the Gobi Desert. The Xiongnu leader was forced to flee far north. This battle was costly for Han, as they lost many warhorses. The high cost of the war led to new taxes, which burdened the peasants.

Conquering the Korean Peninsula

Emperor Wu also launched invasions into the northern Korean Peninsula. In 108 BC, he completed the Han conquest of Gojoseon (in modern North Korea and Manchuria). Han Chinese settlers moved into these areas. They often faced raids from local kingdoms but also traded peacefully, and Chinese culture influenced the Korean peoples.

Diplomacy and Exploration

Emperor Wu sent his envoy Zhang Qian to the "Western Regions" (Central Asia) in 139 BC. Zhang Qian's mission was to find the Yuezhi kingdom and form an alliance against the Xiongnu. Zhang Qian was captured by the Xiongnu but escaped and reached Yuezhi. Although Yuezhi did not return to their old lands, they and other kingdoms in the area, like Dayuan and Kangju, started diplomatic ties with Han China. Zhang Qian returned in 126 BC, bringing back valuable information about these distant lands. This opened the way for regular contact between Han and the Western Regions.

Emperor Wu also wanted to expand to the southwest. His plan was to gain control of tribal kingdoms there, like Yelang, to create a route for a possible attack on Nanyue. Han ambassadors gave gifts to these kings, and some submitted. Later, Zhang Qian's report suggested that India and Parthia could be reached through these southwestern kingdoms. So, Emperor Wu sent more ambassadors in 122 BC to persuade Yelang and Dian (modern eastern Yunnan) to submit again.

In 109 BC, Emperor Wu sent an army against the Kingdom of Dian. The King of Dian surrendered, and his kingdom became part of Han territory. Emperor Wu allowed the King of Dian to keep his title.

In 108 BC, Han forces also brought the kingdoms of Loulan and Cheshi (in modern Xinjiang) under control. In 105 BC, Emperor Wu arranged a marriage between a Han princess and the King of Wusun (in Central Asia), creating a strong alliance.

A famous war happened in 104 BC against the Kingdom of Dayuan (modern Kokand). Emperor Wu wanted their best horses, but Dayuan refused. After a long war, Han forces won in 102 BC, capturing 3,000 prized horses. This victory further showed Han's power to the kingdoms of the Western Regions.

Religion and Beliefs

Emperor Wu was very interested in religion and spiritual matters. He worshipped a god called Tai Yi, who his shaman advisers introduced to him. He even built a special chapel for this god at his palace. He also organized important religious ceremonies, and hymns were written for these events.

Emperor Wu was fascinated by the idea of immortality. He associated with magicians who claimed they could create special pills to make him live forever. However, he was very strict about others using magic.

Challenges and Later Years

Emperor Wu began to trust officials who were very harsh in their punishments. He believed this would keep social order. This led to many people being punished severely. For example, in 122 BC, Liu An, a royal relative, and his brother were accused of plotting against the emperor. They took their own lives, and their families were executed.

Emperor Wu started to travel around the empire a lot, visiting different places and worshipping gods, perhaps still hoping for immortality. These trips were very expensive and put a strain on the country's money.

To deal with the high costs of his wars and spending, Emperor Wu's agricultural minister, Sang Hongyang, came up with a plan. The government created national monopolies for salt and iron. This meant the government controlled the production and sale of these important goods. The government also bought other goods when prices were low and sold them when prices were high, making a profit and helping to stabilize prices.

Around 100 BC, due to heavy taxes and military duties, many peasant revolts broke out. Emperor Wu made officials responsible with their lives if revolts were not stopped. This led officials to hide the revolts instead.

The Crown Prince's Rebellion

In 94 BC, Emperor Wu had a new son, Liu Fuling, when he was 62 years old. This led to rumors that he might want to make this young son the crown prince instead of his older son, Crown Prince Ju.

Crown Prince Ju was generally kind and favored leniency, while Emperor Wu's advisers were often harsh. After some of his strong allies died, Crown Prince Ju had fewer supporters in the government. Some officials began to plot against him.

A secret intelligence chief, Jiang Chong, and another official, Su Wen, accused many people of witchcraft. They decided to use this accusation against Crown Prince Ju. With Emperor Wu's approval, Jiang searched the Crown Prince's palace, claiming to look for witchcraft items. He secretly planted dolls and writings, then announced he had found them.

Crown Prince Ju was shocked and knew he was being framed. His teacher suggested he start an uprising, thinking Emperor Wu might be dead. Prince Ju hesitated but decided to act when he learned Jiang's messengers were already on their way to report him.

Prince Ju arrested Jiang and killed him, accusing him of trying to ruin his relationship with his father. Su Wen escaped and told Emperor Wu that Prince Ju was rebelling. Emperor Wu, believing this false report, ordered his nephew to put down the rebellion.

For five days, the two sides fought in the streets of Chang'an. Prince Ju's forces were defeated. He fled the capital with two of his sons and some guards. His mother, Empress Wei, took her own life. Many of his supporters were punished.

Emperor Wu was still very angry and ordered Prince Ju to be found. However, an official risked his life to speak on Prince Ju's behalf, and Emperor Wu's anger began to lessen.

Prince Ju hid in a poor peasant family's home. When he sought help from an old friend, his location was discovered. Surrounded by soldiers, he took his own life. His two sons and the family housing them also died. The officials who found him were rewarded.

Emperor Wu's Final Years

After Jiang Chong and Prince Ju died, the witchcraft accusations continued. General Li Guangli, a relative of a favorite concubine, was accused of using witchcraft against Emperor Wu. Li's family was arrested and executed. Li himself defected to the Xiongnu.

By this time, Emperor Wu realized that many witchcraft accusations had been false, especially regarding his son's rebellion. He had Su Wen burned and Jiang Chong's family executed. He also appointed a new prime minister who favored peace and helping the people. These policies were similar to what Crown Prince Ju had supported. Emperor Wu publicly apologized to the nation for his past mistakes, an event known as the Repenting Edict of Luntai.

In 88 BC, Emperor Wu became seriously ill. With Crown Prince Ju gone, there was no clear heir. He decided his youngest son, Liu Fuling, who was only six, was the most suitable. He chose Huo Guang to be the regent, meaning Huo would rule until Fuling was old enough. Emperor Wu also ordered the execution of Prince Fuling's mother, Lady Gouyi, fearing she might become too powerful like a previous empress dowager. He died in 87 BC, and Liu Fuling became Emperor Zhao.

Emperor Wu was buried in the Maoling mound, a famous Chinese pyramid.

Emperor Wu's Lasting Impact

Historians have mixed feelings about Emperor Wu. He greatly expanded the Han Empire, and much of the land he conquered is now part of modern China. He officially promoted Confucianism, but he also used a strict system of rewards and punishments to govern, similar to the earlier Qin Shi Huang.

Emperor Wu was known for being extravagant and superstitious, which sometimes burdened his people. His punishments for failures were often very harsh.

One of his biggest changes was strengthening the Emperor's power. The role of Shangshu (court secretaries) became very important, acting as the Emperor's close advisers. This continued for centuries.

In 140 BC, Emperor Wu held a special examination for over 100 young scholars, many from ordinary backgrounds. This was a major event, marking the official start of Confucianism as the main imperial teaching. A young Confucian scholar named Dong Zhongshu wrote the best essay, supporting Confucian ideas.

In 136 BC, Emperor Wu founded the Imperial University. This college trained scholars in classical texts to become government officials.

Poetry and Music

Emperor Wu was very interested in poetry and supported poets. Some poems about lost love are even said to be written by him.

He also helped bring back interest in Chu ci, a style of poetry from the old Chu kingdom. This type of poetry was linked to shamanism, and Emperor Wu supported both the poetry and the shamanic rituals.

Emperor Wu hired poets and musicians to create songs and dances for performances. He loved these grand rituals, especially at night with thousands of torches lighting up the singers, musicians, and dancers.

The fu style of Han poetry also developed in his court, with Sima Xiangru as a leading poet.

Another major contribution was his organization of the Imperial Music Bureau (yuefu). This office was in charge of music and poetry. It collected popular songs from around the country and adapted them, and also developed new music. The Music Bureau helped spread a special style of poetry known as the "Music Bureau" style, or yuefu.

Era Names During His Reign

- Jianyuan (建元) 140 BC – 135 BC

- Yuanguang (元光) 134 BC – 129 BC

- Yuanshuo (元朔) 128 BC – 123 BC

- Yuanshou (元狩) 122 BC – 117 BC

- Yuanding (元鼎) 116 BC – 111 BC

- Yuanfeng (元封) 110 BC – 105 BC

- Taichu (太初) 104 BC – 101 BC

- Tianhan (天漢) 100 BC – 97 BC

- Taishi (太始) 96 BC – 93 BC

- Zhenghe (征和) 92 BC – 89 BC

- Houyuan (後元) 88 BC – 87 BC

Family Members

Emperor Wu had several wives and many children:

- Empress Chen (166/165–c. 110 BC), his first cousin.

- Empress Xiaowusi (d. 91 BC)

- Eldest Princess Wei

- Princess Zhuyi (d. 91 BC)

- Princess Shiyi (d. 91 BC)

- Liu Ju, Crown Prince Wei (128–91 BC), his first son.

- Lady Li

- Liu Bo, Prince Ai of Changyi (d. 88 BC), his fifth son.

- Lady Guoyi (113–88 BC)

- Liu Fuling, Emperor Xiaozhao (94–74 BC), his sixth son.

- Lady Wang (d. 121 BC)

- Liu Hong, Prince Huai of Qi (123–110 BC), his second son.

- Lady Li

- Liu Dan, Prince La of Yan (d. 80 BC), his third son.

- Liu Xu, Prince Li of Guangling (d. 54 BC), his fourth son.

- Unknown mothers:

- Princess Eyi (d. 80 BC)

- Princess Yangshi (d. 92 BC)

- Princess Yi'an

Emperor Wu in Pop Culture

Emperor Wu is a very famous figure in Chinese history and has appeared in many Chinese TV dramas, such as:

- The Prince of Han Dynasty

- The Emperor in Han Dynasty

- Beauty's Rival in Palace

- The Virtuous Queen of Han

He is also a main character in Carole Wilkinson's novel Dragonkeeper and its sequels. These books tell the story of a former slave girl and dragons, showing parts of Emperor Wu's early reign and his search for immortality.

In the 1991 movie "The Addams Family," Morticia Addams mentions "a finger trap from the court of Emperor Wu."

Images for kids

-

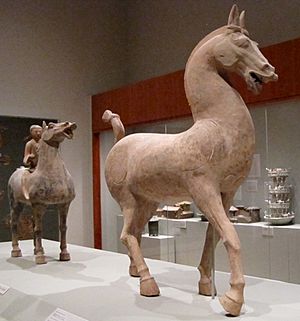

Chinese ceramic statues of cavalry and infantry, wearing armour and bearing shields (with missing weapons), from a Western Han tomb, Hainan Provincial Museum

-

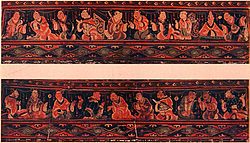

Ceramic figurines of soldiers, both infantry and cavalry, Western Han period, Shaanxi History Museum, Xi'an

-

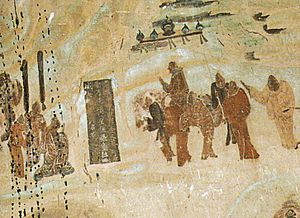

Detail of the gilded incense burner given by Emperor Wu to Wei Qing as an imperial gift; Shaanxi History Museum

See also

In Spanish: Wu de Han para niños

In Spanish: Wu de Han para niños

- Family tree of the Han dynasty