Han dynasty facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Han

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||

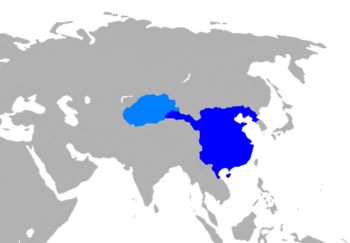

A map of the Western Han dynasty in 2 AD

|

|||||||||||||||

| Capital | Chang'an (206 BC – 9 AD, 190–195 AD) Luoyang (23–190 AD, 196 AD) Xuchang (196–220 AD) |

||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Chinese | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Daoism Chinese folk religion |

||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||

|

• 202–195 BC (first)

|

Emperor Gaozu | ||||||||||||||

|

• 141–87 BC

|

Emperor Wu | ||||||||||||||

|

• 74–48 BC

|

Emperor Xuan | ||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||||||||

|

• 206–193 BC

|

Xiao He | ||||||||||||||

|

• 193–190 BC

|

Cao Can | ||||||||||||||

|

• 189–192 AD

|

Dong Zhuo | ||||||||||||||

|

• 208–220 AD

|

Cao Cao | ||||||||||||||

|

• 220 AD

|

Cao Pi | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Imperial | ||||||||||||||

| 206 BC | |||||||||||||||

|

• Battle of Gaixia; Liu Bang proclaimed emperor

|

202 BC | ||||||||||||||

| 9–23 AD | |||||||||||||||

|

• Abdication to Cao Wei

|

220 AD | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 50 BC est. (Western Han peak) | 6,000,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| 100 AD est. (Eastern Han peak) | 6,500,000 km2 (2,500,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

|

• 2 AD

|

57,671,400 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Ban Liang coins and Wu Zhu coins | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Vietnam North Korea |

||||||||||||||

| Han dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

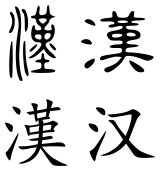

"Han" in ancient seal script (top left), Han-era clerical script (top right), modern Traditional (bottom left), and Simplified (bottom right) Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hàn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Han dynasty (Chinese: 漢朝; pinyin: Hàncháo) was a powerful Chinese empire that lasted for over 400 years (202 BC – 9 AD, and 25–220 AD). It was started by Liu Bang, also known as Emperor Gao. This period is often called a "golden age" in Chinese history. It greatly shaped the identity of the Chinese civilization that we know today.

Today, most people in China call themselves "Han people." Their language is known as "Han language," and their writing is called "Han characters."

Contents

What Does "Han" Mean?

The name "Han" comes from the Han River. After the Qin dynasty fell, a powerful leader named Xiang Yu made Liu Bang the prince of a small area called Hanzhong. This area was named after the river. When Liu Bang won the war and started his own empire, he named it the Han dynasty after his first territory.

A Look at Han History

The Han dynasty came after the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC). There was a period of fighting called the Chu–Han Contention (206–202 BC) before the Han began. After the Han dynasty ended, China entered the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 AD).

There was a brief break in the middle of the Han dynasty. A powerful official named Wang Mang took over and started his own Xin dynasty (9–23 AD). Because of this, the Han dynasty is split into two parts: the Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD) and the Eastern Han (25–220 AD).

How the Han Government Worked

The emperor was the most important person in Han society. He led the government but shared power with noble families and wise ministers. These ministers were often scholars.

The Han Empire was divided into areas directly controlled by the central government, called commanderies. There were also some kingdoms that had a bit more freedom. Over time, these kingdoms lost their independence, especially after the Rebellion of the Seven States. From the time of Emperor Wu (141–87 BC), the government officially supported Confucianism. This way of thinking guided education and politics until 1912 AD.

Han Dynasty Economy

The Han dynasty was a time of great wealth and growth. The use of money, which started in the Zhou dynasty (around 1050–256 BC), became very important. The coins made by the government in 119 BC were used in China until the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD).

To pay for its military campaigns and to settle new lands, the Han government took control of the private salt and iron industries in 117 BC. This meant the government owned these businesses. However, these government monopolies were later ended during the Eastern Han dynasty.

Han Dynasty Conflicts

The Han dynasty often fought with the Xiongnu, a group of nomadic people from the north. The Xiongnu defeated the Han in 200 BC. For many decades, the Han had to pay tribute to the Xiongnu and still faced raids on their borders.

This changed in 133 BC, during Emperor Wu's rule. Han forces started many strong military attacks against the Xiongnu. The Han won these battles, and the Xiongnu had to accept Han rule. These campaigns also helped create the famous Silk Road. This trade route reached as far as the Mediterranean world. The Silk Road was important for trade and culture, but it was very costly to manage.

Emperor Wu also led successful military trips to the south. He took over Nanyue in 111 BC and Dian in 109 BC. He also expanded Han land into the northern Korean Peninsula. Han forces conquered Gojoseon and set up new areas called Xuantu and Lelang Commanderies in 108 BC.

The End of the Han Dynasty

After 92 AD, powerful families connected to the empresses fought for control. These power struggles led to the Han dynasty's downfall. After Emperor Ling died (168–189 AD), military leaders and nobles became powerful warlords. They divided the empire among themselves.

The Han dynasty officially ended when Cao Pi, the king of Wei, took the throne from Emperor Xian.

Han Culture and Society

Social Classes in Han China

The emperor was at the very top of Han society. However, sometimes the emperor was young, and a regent (like the empress dowager or her male relatives) would rule for him. Below the emperor were the kings, who were part of the same Liu family. Everyone else, except for slaves, belonged to one of twenty social ranks.

Each higher rank gave people more benefits and legal rights. The highest rank, a full marquess, came with a government payment and a piece of land.

By the Eastern Han period, local scholars, teachers, students, and government officials started to see themselves as part of a larger, educated class. They shared similar values and a love for learning.

Farmers who owned their land were ranked just below scholars and officials. Other farm workers, like tenants, paid laborers, and slaves, had a lower status. Artisans, technicians, traders, and craftspeople were ranked between land-owning farmers and common merchants.

Merchants who were officially registered with the state had to wear white clothes and pay high taxes. The educated class often looked down on them. These were usually small shopkeepers in cities. However, some merchants, like those who traded between cities, could avoid registering. They were often richer and more powerful than most government officials.

Doctors, pig breeders, and butchers had a fairly high social standing. People who told fortunes, runners, and messengers had a lower status.

Marriage, Family, and Gender Roles

Right: A dog figurine found in a Han tomb wearing a decorative dog collar. This shows dogs were kept as pets.

Han families were usually small, with about four or five people living together. The family line was traced through the father.

Marriages were very formal, especially for rich families. Giving gifts, like bridewealth and dowry, was very important. Not having these gifts was seen as shameful. Marriages were usually arranged by parents. The father's opinion on who his child married was more important than the mother's.

Both men and women could get a divorce and remarry under certain conditions. However, a woman whose husband died still belonged to his family. If she wanted to remarry, her original family had to pay a fee to get her back. Her children would stay with her late husband's family.

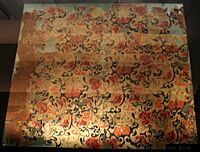

Right image: A Han pottery female dancer in silk robes.

Women were expected to obey their father, then their husband, and then their adult son when they were old. Most women wove clothes for their families, to sell, or for large textile companies. Other women helped on their brothers' farms. Some became singers, dancers, sorceresses, respected doctors, or successful merchants. These successful merchants could afford their own silk clothes.

Education, Books, and Ideas

The Imperial University became very important, with over 30,000 students by the 2nd century CE. Education based on Confucian ideas was also available at local schools and private schools in small towns. Teachers earned good money from tuition. Schools were even set up in far southern regions to help local people learn Chinese texts.

Many important books were written and studied. Philosophers like Yang Xiong, Huan Tan, Wang Chong, and Wang Fu wrote about whether human nature was good or evil. The Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Tan and his son Sima Qian set the standard for all future Chinese history books. The Book of Han was written by Ban Biao, his son Ban Gu, and his daughter Ban Zhao. There were also dictionaries like the Shuowen Jiezi by Xu Shen and the Fangyan by Yang Xiong.

Biographies of important people were also written. Han dynasty poetry was mostly in the fu style, which was most popular during Emperor Wu's rule.

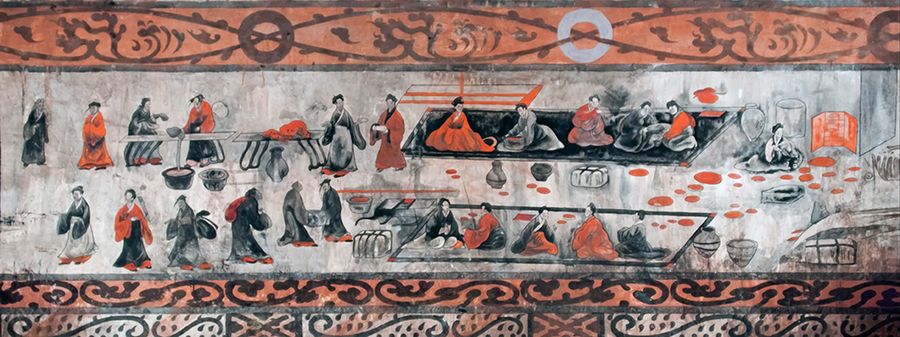

Food in Han China

The main foods eaten during the Han period were wheat, barley, different types of millet, rice, and beans. Common fruits and vegetables included chestnuts, pears, plums, peaches, melons, apricots, strawberries, red bayberries, jujubes, calabash, bamboo shoots, mustard plant, and taro. Animals like chickens, Mandarin ducks, geese, cows, sheep, pigs, camels, and dogs were also eaten. Some dogs were raised specifically for food, while others were pets. Turtles and fish were caught from rivers and lakes. People also hunted animals like owls, pheasants, magpies, sika deer, and Chinese bamboo partridge. Seasonings included sugar, honey, salt, and soy sauce. Beer and wine were regularly consumed.

Han Clothing Styles

The clothes people wore and the materials they used depended on their social class. Rich people could afford silk robes, skirts, socks, and mittens. They also wore coats made of badger or fox fur, duck feathers, and slippers decorated with leather, pearls, and silk. Farmers usually wore clothes made of hemp, wool, and ferret skins.

Religion and Beliefs

Families throughout Han China offered animals and food to gods, spirits, and ancestors at temples and shrines. People believed that each person had a two-part soul. The spirit-soul (hun) went to an afterlife paradise. The body-soul (po) stayed in the grave or tomb. It could only reunite with the spirit-soul through a special ceremony.

The emperor also served as the highest priest. People believed that if the emperor did not act properly, he could upset the balance of the universe. This could cause disasters like earthquakes, floods, droughts, diseases, and swarms of locusts.

It was thought that people could become immortal if they reached the lands of the Queen Mother of the West or Mount Penglai.

Buddhism first came to China through the Silk Road during the Eastern Han period. It was first mentioned in 65 CE. China's first known Buddhist temple, the White Horse Temple, was built outside the capital city of Luoyang during Emperor Ming's rule. Important Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese in the 2nd century CE.

Science and Technology in Han China

The Han dynasty was a special time for science and technology in ancient China. It was as advanced as the Song dynasty (960–1279). Many important inventions and discoveries were made. These include papermaking, the ship's rudder, using negative numbers in math, the raised-relief map, the hydraulic-powered armillary sphere for astronomy, and a seismometer that could detect earthquakes.

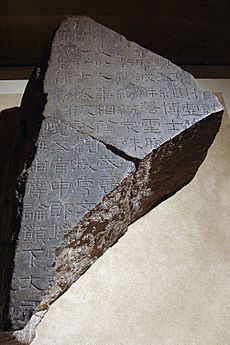

Writing Materials and Paper

Before the Han dynasty, people in China wrote on bronze items, animal bones, and bamboo slips or wooden boards. By the start of the Han dynasty, the main writing materials were clay tablets, silk cloth, hemp paper, and scrolls made from bamboo strips sewn together.

The oldest known piece of Chinese hemp paper is from the 2nd century BC. The standard way of making paper was invented by Cai Lun (AD 50–121) in 105 AD. The oldest surviving piece of paper with writing on it was found in the ruins of a Han watchtower in Inner Mongolia. It was abandoned in 110 AD.

Machines and Water Power

In 15 BC, the philosopher Yang Xiong described the invention of the belt drive for a machine that made silk threads. This was very important for making textiles. Around 180 AD, the engineer Ding Huan created a fan that was turned by hand to provide air conditioning in palace buildings.

The waterwheel appeared in Chinese records during the Han dynasty. Waterwheels were used to turn gears that lifted heavy hammers to pound, thresh, and polish grain. Du Shi (died 38 AD), an engineer and metallurgist, created a waterwheel-powered machine that worked the bellows for melting iron. Waterwheels were also used to power chain pumps that lifted water for irrigation.

The armillary sphere, a model of how things move in the sky, was invented in Han China by the 1st century BC. Using a water clock, a waterwheel, and gears, the astronomer Zhang Heng (AD 78–139) could make his metal armillary sphere spin by itself.

Zhang also invented a device he called an "earthquake weathervane." This was the first seismograph. It could tell the exact direction of earthquakes hundreds of kilometers away. It used a special pendulum that, when shaken by ground tremors, would trigger gears. This would cause a metal ball to drop from one of eight dragon mouths (representing directions) into a metal toad's mouth.

-

A Han-dynasty pottery model of two men using a winnowing machine with a crank handle and a tilt hammer to pound grain.

-

A modern copy of Zhang Heng's seismometer.

Mathematics in Han China

One of the Han dynasty's biggest math achievements was the world's first use of negative numbers. Negative numbers were also used by the Greek mathematician Diophantus around 275 AD, but they were not widely accepted in Europe until the 16th century.

The Han people used math in many different areas. In musical tuning, Jing Fang (78–37 BC) figured out that 53 perfect fifths were almost equal to 31 octaves. He did this while creating a musical scale of 60 tones.

Astronomy and the Cosmos

During the 5th century BC, the Chinese created the Sifen calendar. It measured the year as 365.25 days long. In 104 BC, this was replaced with the Taichu calendar, which was even more accurate. However, Emperor Zhang later brought back the Sifen calendar.

Han Chinese astronomers made star catalogues and kept detailed records of comets. They even recorded the appearance of what we now call Halley's Comet in 12 BC.

Han dynasty astronomers believed in a geocentric model of the universe. This meant they thought the Earth was at the center, surrounded by a sphere. They believed the Sun, Moon, and planets were round, not flat. They also knew that the Moon and planets shone because of sunlight. They understood that lunar eclipses happened when the Earth blocked sunlight from reaching the Moon. They also knew that a solar eclipse happened when the Moon blocked sunlight from reaching the Earth. Although some disagreed, Wang Chong correctly described the water cycle, explaining how water evaporates into clouds.

Maps, Ships, and Vehicles

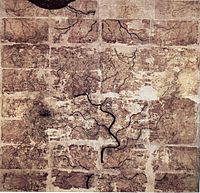

The general Ma Yuan created the world's first known raised-relief map using rice in the 1st century. There is also evidence that in the early 2nd century, the mapmaker Zhang Heng was the first to use scales and grids on maps.

Han dynasty Chinese sailed in many different types of ships. The junk ship design was developed during the Han era. Junk ships had square ends, a flat bottom or a curved hull without a keel, and solid walls inside instead of ribs. Han ships were also the first in the world to use a rudder at the back for steering. This was better than the simpler steering oar and allowed them to sail on the open seas.

While ox-carts and chariots were used before, the wheelbarrow was first used in Han China in the 1st century BC. Han artwork of horse-drawn chariots shows that the heavy wooden yoke around a horse's chest was replaced by a softer breast strap. Later, the full horse collar was invented.

-

An early Western Han dynasty silk map found in a tomb in Mawangdui. It shows the Kingdom of Changsha and Kingdom of Nanyue in southern China.

Medicine and Healing

Han-era doctors believed that the human body was affected by the same natural forces as the universe. These included the cycles of yin and yang and the five phases. Each organ in the body was linked to a specific phase. Illness was seen as a sign that the qi or "vital energy" channels to an organ were blocked. So, Han doctors prescribed medicines that they believed would fix this imbalance.

For example, since the wood phase was thought to help the fire phase, medicines linked to wood could be used to heal an organ linked to fire. When the Chinese doctor Hua Tuo (died 208 AD) performed surgery, he used anesthesia to numb his patients' pain. He also prescribed a special ointment that was said to speed up the healing of surgical wounds.

See also

In Spanish: Dinastía Han para niños

In Spanish: Dinastía Han para niños