Trip hammer facts for kids

A trip hammer is a huge, powerful hammer. People used them a long time ago for many tasks. In farming, they would pound and clean grains. In mining, they crushed metal ores into smaller pieces, though a stamp mill was more common for this. Blacksmiths also used them to shape hot metal, like turning wrought iron into useful bars. They were also great for making things from brass, steel, and other metals.

These hammers were usually set up in a special workshop called a forge or hammer mill. A spinning part called a cam would lift the hammer, and then it would drop down with the force of gravity. In the past, trip hammers were often powered by water wheels.

Trip hammers were used in Imperial China as early as the Western Han dynasty. They also existed in the ancient Greco-Roman world. More evidence of their use appeared in medieval Europe around the 12th century. Later, during the Industrial Revolution, newer machines like the power hammer replaced trip hammers. Often, many hammers would be powered by a central engine using line shafts, pulleys, and belts.

Contents

Ancient History of Trip Hammers

China

In ancient China, the trip hammer developed from the simple mortar and pestle. People then created a foot-operated version called a tilt-hammer. This was a basic machine with a lever and a pivot. You would step on one end to lift the other. This made the hard work of pounding grain much easier than doing it by hand.

Some Chinese historians believe trip hammers existed as far back as the Zhou dynasty (1050 BC–221 BC). However, experts like Joseph Needham say the first clear descriptions are from books written around 40 BC to 20 AD. One book, the Xin Lun by Huan Tan, even says the legendary king Fu Xi invented the pestle and mortar, which led to the trip hammer. This book also suggests that water-powered trip hammers were widely used in China by the 1st century AD.

An old text says: "Fu Hsi invented the pestle and mortar, which is so useful, and later on it was cleverly improved in such a way that the whole weight of the body could be used for treading on the tilt-hammer, thus increasing the efficiency ten times. Afterwards the power of animals—donkeys, mules, oxen, and horses—was applied by means of machinery, and water-power too used for pounding, so that the benefit was increased a hundredfold."

Later, two pictures from the Han era show that water wheels were used to power many trip hammers at once. The Chinese term for water-powered trip-hammer became shuǐ duì. A scholar named Ma Rong (79–166 AD) wrote about hammers "pounding in the water-echoing caves." In 129 AD, an official reported that trip hammers were being sent from China to other regions.

By the 3rd century AD, an engineer named Du Yu created "combined trip hammer batteries." These used several hammers powered by one large water wheel. Chinese texts from the 4th century mention people owning and operating hundreds of trip hammer machines. Trip hammers were also common during the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) and Song dynasty (960–1279). Records from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) show them being used in papermills.

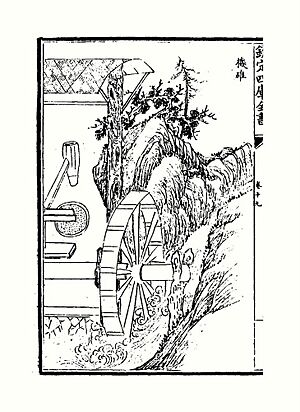

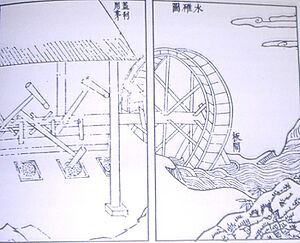

Chinese trip hammers sometimes used efficient vertical water wheels. However, they often used horizontal water wheels, especially with hammers that lay flat (recumbent hammers). Pictures of these flat hammers appeared in a book by Wang Zhen in 1313 AD. More illustrations were in an encyclopedia from 1637 by Song Yingxing.

Europe

Greco-Roman World

The main parts of water-powered trip hammers – water wheels, cams, and hammers – were already known in ancient Greece and Rome. Early cams were seen in water-powered robots from the 3rd century BC.

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder mentioned in the 1st century AD that water-driven pestles were common in Italy. He wrote: "The greater part of Italy uses an unshod pestle and also wheels which water turns as it flows past, and a trip-hammer."

While some thought this meant a watermill, later studies suggested mola referred to water-powered trip hammers used for pounding grain. These machines were still known in the early Middle Ages. For example, a monastery in the 5th century AD used grain-pounders with pestles.

Archaeologists found an ancient Roman water mill at Saepinum in Italy. It might have used trip hammers for tanning leather. This is the earliest sign of such use in ancient times.

Trip hammers were most widely used in Roman mining. They crushed metal ore from deep mines into small pieces for further processing. The regular marks on stone anvils show that cam-operated ore stamps were used, similar to those in later medieval mining. These anvils have been found at many Roman silver and gold mines in Western Europe, including Dolaucothi in Wales and in Spain and Portugal. The examples found date from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. At Dolaucothi, these trip-hammers were powered by water. Roman mines often had plenty of water from their large-scale washing techniques, which could power these machines.

Medieval Europe

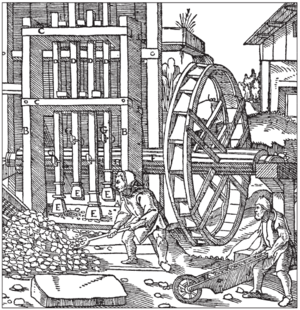

Water-powered trip hammers reappeared in medieval Europe by the 12th century. Records from Austria (1135, 1175 AD) and France (1116, 1249 AD) describe their use in forging wrought iron. By the 15th century, medieval European trip hammers were often vertical pestle stamp-mills. They used vertical water wheels more often than earlier Chinese versions.

The famous artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci often drew trip hammers for forges and even for machines that cut files. The oldest known European picture of a forge-hammer is from a book by Olaus Magnus in 1565 AD. This picture shows three hammers and a water wheel working the bellows of a furnace. The flat (recumbent) hammer was first shown in European art in 1621 AD.

Types of Trip Hammers

A trip hammer has its heavy head at the end of a long handle called a helve. This is why they are also called helve hammers. The helve was usually made of wood and pivoted in a cast-iron ring. Later, some very heavy helves were made entirely of cast iron.

The tilt hammer or tail helve hammer has its pivot in the middle of the helve. It is lifted by pushing down the end opposite to the hammer head. These hammers usually had a head weighing about 50 kilograms (100 pounds). They could strike very quickly, which was good for shaping iron into small sizes, perfect for making cutlery. Many forges near Sheffield were called 'tilts' because of this. They were also used in brass works to make brass or copper pots. In Germany, tilt hammers up to 300 kg were used to forge iron. You can still see working water-powered tilt hammers today, for example, at the Frohnauer Hammer in Germany.

The belly helve hammer was commonly found in a finery forge. It was used to turn pig iron into usable bar iron. Cams would strike the helve between the pivot and the hammer head to lift it. The head usually weighed about a quarter of a ton. This design was likely used because a heavier head would put too much strain on a wooden helve.

The nose helve hammer was less common until the late 1700s or early 1800s. This hammer was lifted from the end beyond the head. The nose helves seen in pictures and those that still exist appear to be made of cast iron.

End of the Trip Hammer

The steam-powered drop hammer eventually replaced the trip hammer, especially for very large metal pieces. James Nasmyth invented it in 1839 and patented it in 1842. By then, shaping metal with hammers became less important because of improvements to the rolling mill and new ways of making iron. However, hammers were still needed for some tasks, like shingling (shaping hot metal into slabs).

See also

- Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet

- Dorfchemnitz Iron Hammer Mill

- Finch Foundry

- Freibergsdorf Hammer Mill

- Frohnauer Hammer Mill

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |