Steam hammer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Steam hammer |

|

|---|---|

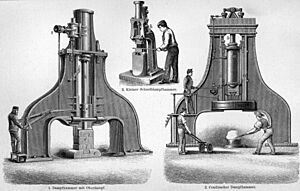

1894 illustration of various sizes of single- and double-frame steam hammer

|

|

| Industry | Metal working |

| Application | Forging, pile driving, riveting etc. |

| Fuel source | Wood or coal |

| Inventor | François Bourdon, James Nasmyth |

| Invented | 1839 |

A steam hammer, also known as a drop hammer, is a strong machine that uses steam power. It's used in factories to shape metal or to push large poles (called piles) into the ground. Imagine a giant hammer that moves up and down very fast!

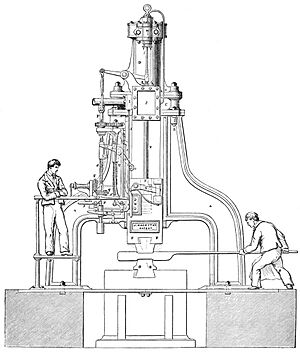

Usually, the hammer part is connected to a piston. This piston slides inside a fixed tube called a cylinder. Sometimes, it's the other way around: the hammer is attached to the cylinder, which slides along a fixed piston.

The idea for a steam hammer came from James Watt in 1784. But it wasn't until 1840 that the first working steam hammer was built. This was needed to make bigger and bigger metal parts for new machines. Two inventors, François Bourdon from France and James Nasmyth from Britain, both claimed to have invented it around the same time. Bourdon built the first one, but Nasmyth said it was based on his own design.

Steam hammers became super important in many industries. They got better over time, allowing for more control, lasting longer, and hitting with more power. A huge steam hammer built in 1891 could hit with the force of 125 tons! In the 1900s, other machines like mechanical and hydraulic presses started to replace steam hammers for shaping metal. However, some steam hammers are still used today. Also, machines that use compressed air, which are like modern steam hammers, are still made.

Contents

How a Steam Hammer Works

A steam hammer works by using steam pressure. In a simple type, called a "single-acting" hammer, steam pushes the hammer up. Then, the steam is released, and the hammer drops down with gravity.

Most steam hammers are "double-acting." This means steam is used to push the hammer up AND to push it down. This makes the hammer hit with much more force. The heavy part of the hammer, called the ram, can weigh from 225 kilograms (about 500 pounds) to 22,500 kilograms (about 50,000 pounds)!

The metal piece being worked on is placed between two special tools called dies. One die sits on a heavy block, and the other is attached to the hammer. When the hammer drops, it shapes the metal.

Early steam hammers were built from many parts bolted together. This was because the constant hitting could break cast iron parts. Bolting them together made it easier to replace broken pieces. It also made the hammer a bit flexible, which helped prevent it from breaking.

Hammer Designs

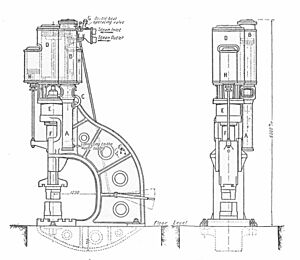

A steam hammer can have one or two support frames.

- A single-frame design lets the worker move around the dies more easily.

- A double-frame design can support a much more powerful hammer.

The frames and the heavy block underneath are placed on wooden beams. These beams help absorb the shock and protect the concrete foundation below. Even with these protections, a very large steam hammer can still shake the building!

To solve this, some hammers are "counterblow" steam hammers. Instead of hitting an anvil below, two hammers move towards each other. One hammer comes down, and another hammer comes up. They hit the metal piece in the middle. These hammers create a huge impact and can make very large metal parts. They also need smaller foundations because the force is absorbed between the two hammers, not pushed into the ground. Counterblow hammers are more common in Europe than in the United States.

Controlling the Blow

Some early steam hammers needed a worker to control each hit by hand. Others had an automatic system that allowed for fast, repeated hammering. These automatic hammers could work in two ways:

- An elastic blow used steam to cushion the hammer at the end of its downward movement. This made it hit faster but with less force.

- A dead blow had no cushioning, giving a stronger hit.

Machines were built that could switch between these two modes. The force of the hit could also be changed by adjusting how much steam was used to cushion the blow. Today, some modern air/steam hammers can deliver up to 300 hits every minute!

History of the Steam Hammer

The First Ideas

The idea of a steam hammer was first written down by James Watt in 1784. He was famous for improving the steam engine. Watt described how a hammer could be attached directly to a steam engine's piston. This would let it forge metal without needing wheels or other moving parts.

Later, in 1806, W. Deverell patented a steam-powered hammer. His design had the hammer attached to a piston inside a cylinder. Steam would push the piston up, and then compressed air would push it down.

In 1827, John Hague patented a way to use air power for hammers. He made a hammer that worked so fast you couldn't even see it move! However, it was hard to control how hard it hit.

The Invention Story

It seems that James Nasmyth from Scotland and François Bourdon from France both came up with the idea of the steam hammer on their own in 1839. They were both trying to solve the same problem: how to make very large metal shafts for the growing steam engines used in trains and boats.

Nasmyth said he designed his steam hammer when a huge shaft was needed for a new ship, the SS Great Britain. He made a sketch of his design in November 1839. However, the ship's design changed, and the immediate need for the giant shaft disappeared. Nasmyth still showed his design to everyone who visited his workshop.

Bourdon also had the idea for his "Pilon" (hammer) in 1839. He made detailed drawings and showed them to engineers who visited the Schneider & Cie factory in France. The factory owners, the Schneider brothers, were unsure about building Bourdon's new machine.

In 1840, Bourdon and Eugène Schneider visited Nasmyth's workshop in England. There, they saw Nasmyth's sketch. This made Schneider realize the idea was possible! So, in 1840, Bourdon built the very first working steam hammer at the Schneider & Cie factory in France. It weighed 2,500 kilograms (about 5,500 pounds) and could lift 2 meters (about 6.5 feet) high. The Schneiders patented the design in 1841.

Nasmyth visited the French factory in 1842. He said Bourdon showed him the hammer and called it "his own child." Nasmyth then built his first steam hammer in England in 1842. In 1843, a disagreement started between Nasmyth and Bourdon about who invented the steam hammer first. Nasmyth was very good at telling his story, and many people believed he was the first.

Early Improvements

Nasmyth's first steam hammer, patented in 1842, was improved by Robert Wilson. Wilson invented a "self-acting" system that could change the force of the hammer's blow. This was a very important improvement! With Wilson's system, Nasmyth's steam hammers could hit with a wide range of forces. Nasmyth loved to show off by breaking an egg in a wineglass without breaking the glass, then hitting with a blow that shook the whole building!

By 1868, engineers had made even more improvements. Some hammers had a fixed piston and a moving cylinder. Others were designed to use compressed air instead of steam, especially in places where steam wasn't available or a very dry environment was needed.

Different companies made their own versions. For example, the Bowling Ironworks made hammers where the steam cylinder was attached to the back, making the machine shorter. John Ramsbottom invented a "duplex hammer" with two hammers moving horizontally towards each other to hit a metal piece in the middle.

Nasmyth also used the same ideas to create a steam-powered machine for driving piles into the ground. His machine could drive a pile in just four and a half minutes, while old methods took twelve hours! It was found that a hammer with a shorter drop but many more hits per minute was better. It drove the pile faster and caused less damage.

Steam hammers were also adapted for other uses, like riveting machines (to join metal parts with rivets) and crushers for mining. In 1883, a book about steam power said that the steam hammer was the greatest improvement ever made in metal forging. It made old tasks easier and allowed for new types of forging that were impossible before.

Later Developments

Between 1843 and 1867, Schneider & Co. built 110 steam hammers. They kept making bigger and bigger machines to handle the demand for large cannons, engine parts, and armor plates, especially as steel became more common than iron.

In 1861, the "Fritz" steam hammer started working at the Krupp factory in Germany. For many years, it was the most powerful hammer in the world, hitting with a 50-ton blow. There's a story that the hammer was named after a machinist named Fritz. The factory owner, Alfred Krupp, told the Emperor that Fritz could control the hammer so perfectly that he could drop it without harming an object on the block. The Emperor put his diamond watch on the block, and Fritz dropped the hammer without touching it! The Emperor gave Fritz the watch as a gift, and Krupp had "Fritz let fly!" engraved on the hammer.

The Schneiders eventually built an even bigger hammer. The Creusot steam hammer was built in 1877 in France. It could deliver a blow of up to 100 tons, making it the largest and most powerful in the world. In 1891, a company in the United States bought the design and built an almost identical hammer that could hit with 125 tons of force!

Eventually, these huge steam hammers became less common. They were replaced by hydraulic and mechanical presses. Presses applied force slowly and evenly, which made sure the metal parts were strong all the way through, without hidden flaws. Presses were also cheaper to run and build, as they didn't need steam or massive foundations.

Today, the 1877 Creusot steam hammer stands as a monument in a town square in France. An original Nasmyth hammer can be seen near his old factory buildings. A larger Nasmyth & Wilson steam hammer is on the campus of the University of Bolton in England.

Steam hammers are still used for driving piles into the ground. While steam is efficient, compressed air is often used instead today. Companies still sell air/steam pile-driving hammers, and some factories still use classic steam hammers for shaping metal.

See also

- Trip hammer

- Power hammer

- Frohnauer Hammer Mill

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |