Zhang Heng facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Zhang Heng

|

|

|---|---|

| 張衡 | |

A stamp of Zhang Heng issued by China Post in 1955

|

|

| Born | AD 78 Nanyang, China

|

| Died | AD 139 (aged 60–61) Luoyang, China

|

| Known for | Seismometer, hydraulic-powered armillary sphere, pi calculation, poetry, universe model, lunar eclipse and solar eclipse theory |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy, mathematics, seismology, hydraulic engineering, geography, ethnography, mechanical engineering, calendrical science, metaphysics, poetry, literature |

| Zhang Heng | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zhang's name in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 張衡 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 张衡 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zhang Heng (Chinese: 張衡; AD 78–139), also known as Chang Heng, was a brilliant Chinese scientist and government official. He lived during the Han dynasty. Zhang Heng was educated in the big cities of Luoyang and Chang'an. He became famous for his work in many fields. These included astronomy, mathematics, and seismology (the study of earthquakes). He was also an hydraulic engineer (someone who designs water systems) and an inventor.

Zhang Heng started his career as a minor government worker in Nanyang. He later became the Chief Astronomer for the emperor. He also served as a Palace Attendant, working closely with the emperor. Zhang Heng was very honest about history and calendars. This sometimes caused disagreements, stopping him from becoming a Grand Historian. He even had some disagreements with powerful palace officials. Because of this, he decided to leave the central court for a while. He went to work as an administrator in the Hejian Kingdom (in what is now Hebei province). Zhang returned home to Nanyang for a short time. Then, in 138, he was called back to the capital. He passed away there a year later, in 139.

Zhang Heng used his deep knowledge of mechanics and gears in many inventions. He created the world's first water-powered armillary sphere. This device helped astronomers observe the sky. He also improved the water clock by adding an extra tank. One of his most famous inventions was the world's first seismoscope. This device could tell the direction of an earthquake up to 500 km (310 mi) away. He also made better calculations for pi. Zhang Heng created a large star catalog, listing about 2,500 stars. He also developed theories about the Moon and its connection to the Sun. He explained that the Moon is round and gets its light from the Sun. He also understood how solar and lunar eclipses happen. His poems, called fu (rhapsody) and shi, were very popular. Zhang received many honors after his death for his smart ideas. Some modern experts compare his work in astronomy to that of the Greek scholar Ptolemy (AD 86–161).

Contents

Zhang Heng's Early Life

Zhang Heng was born in the town of Xi'e. This was in Nanyang Commandery, which is now part of Henan province. His family was well-known but not rich. His grandfather, Zhang Kan, was a governor. He was one of the leaders who helped bring back the Han Dynasty. This happened after the ruler Wang Mang of the Xin Dynasty died. When Zhang Heng was ten, his father passed away. He was then raised by his mother and grandmother.

Zhang was a talented writer from a young age. In 95 AD, he left home to study in the capital cities. These were Chang'an and Luoyang. While traveling to Luoyang, he saw a hot spring near Mount Li. He wrote one of his first poems about it. This poem, "Fu on the Hot Springs," described the many people visiting the springs. These springs later became famous as the "Huaqing Hot Springs." After studying at Luoyang's Taixue (a top school), he knew a lot about classic books. He also became friends with important people. These included the mathematician Cui Yuan and the philosopher Wang Fu. Government officials offered Zhang several jobs. He was even offered a position as an Imperial Secretary. But he was humble and turned them down.

At 23, Zhang returned home. He became an "Officer of Merit in Nanyang." In this role, he managed documents for Governor Bao De. He wrote official papers and speeches for the governor. As an Officer of Merit, he also helped choose people for local jobs. He also recommended people for higher positions in the capital. He spent much of his time writing long poems about the capital cities. When Governor Bao De was called to the capital in 111 AD, Zhang stayed home. He continued his writing. Zhang Heng started studying astronomy at age 30. He then began publishing his works on astronomy and mathematics.

Zhang Heng's Government Career

In 112 AD, Zhang was called to the court of Emperor An of Han. The emperor had heard about Zhang's math skills. Zhang was given a special carriage to travel to Luoyang. This showed his official status. There, he became a court gentleman. He worked for the Imperial Secretariat. He was later promoted to Chief Astronomer for the court. He held this job from 115 to 120 AD under Emperor An. He served again from 126 to 132 AD under the next emperor.

As Chief Astronomer, Zhang worked under the Minister of Ceremonies. This minister was one of the Nine Ministers, just below the top three officials. Zhang's duties included observing the sky and recording unusual events. He also prepared the calendar. He reported which days were lucky and which were unlucky. Zhang was also in charge of a tough reading test. This test was for all candidates wanting to work in the Imperial Secretariat. These candidates had to know at least 9,000 characters. Under Emperor An, Zhang also managed official carriages. He received formal essays about government policy. He also received names of people suggested for official jobs.

In 123 AD, an official named Dan Song suggested changing the Chinese calendar. He wanted to add some old, unofficial teachings. Zhang Heng disagreed. He thought these teachings were not reliable and could cause mistakes. Other officials agreed with Zhang, and the calendar was not changed. However, Zhang's idea to ban these unofficial writings was rejected. Two officials, Liu Zhen and Liu Taotu, were writing the history of the dynasty. They asked to talk to Zhang Heng. But Zhang was not allowed to help them. This was because of his strong opinions against the unofficial writings. It was also because he disagreed about the role of Gengshi Emperor in bringing back the Han Dynasty. Liu Zhen and Liu Taotu were Zhang's only friends in the court who were historians. After they died, Zhang had no more chances to become a court historian.

Despite this, Zhang was again made Chief Astronomer in 126 AD. This happened after Emperor Shun of Han became emperor. Zhang's hard work in astronomy was recognized. He earned a salary of 600 shi (bushels) of grain. This was often paid in money or silk. To give you an idea, the lowest-paid official earned 100 bushels. The highest-paid official earned 10,000 bushels. The 600-bushel rank was the lowest the emperor could directly appoint.

In 132 AD, Zhang showed the court his amazing seismoscope. He said it could find the exact direction of a distant earthquake. One time, his device showed an earthquake in the northwest. No one in the capital felt anything. So, his political rivals thought his device had failed. But soon after, a messenger arrived. He reported that an earthquake had happened about 400 to 500 km (248 to 310 mi) northwest of Luoyang. This was in Gansu province, exactly where Zhang's device had pointed. This proved his invention worked!

A year after Zhang showed his seismoscope, officials were asked to comment on recent earthquakes. Ancient Chinese people believed natural disasters were signs from Heaven. They thought these signs meant the ruler or his officials had done something wrong. Zhang wrote a memorial to the throne (a formal essay) about why these disasters were happening. He criticized a new system for choosing officials. This system set the age for "Filial and Incorrupt" candidates at forty. It also gave the power to assess candidates to the Three Excellencies. Traditionally, this power belonged to the Generals of the Household. Zhang's ideas were rejected. But his position soon improved. He became a Palace Attendant. This allowed him to influence Emperor Shun's decisions. With this important new job, Zhang earned a salary of 2,000 bushels. He also had the right to accompany the emperor.

As Palace Attendant, Zhang Heng tried to convince Emperor Shun that the court eunuchs were a danger. Zhang gave examples of past problems caused by eunuchs. He urged Shun to take more control and limit their power. The eunuchs tried to spread rumors about Zhang. Zhang responded with a long poem called "Fu on Pondering the Mystery." In this poem, he expressed his frustration. Historian Rafe de Crespigny says Zhang's poem used images similar to Qu Yuan's poem "Li Sao." It explored whether good people should leave a corrupt world or stay virtuous within it.

Zhang Heng's Writings and Poems

While working for the government, Zhang Heng could access many books. These were kept in the Archives of the Eastern Pavilion. Zhang read many important history books. He said he found ten times where the Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian and the Book of Han by Ban Gu were different from other old texts. His findings were written down in the 5th-century book Book of Later Han. His long poems (rhapsodies) and other writings showed he knew a lot about classic texts. He also understood Chinese philosophy and history. He also wrote comments on the Taixuan ("Great Mystery") by the Daoist writer Yang Xiong.

Xiao Tong (501–531), a prince of the Liang Dynasty, included several of Zhang's works in his book Selections of Refined Literature. Zhang's fu rhapsodies include "Western Metropolis Rhapsody" and "Eastern Metropolis Rhapsody." They also include "Southern Capital Rhapsody," "Rhapsody on Contemplating the Mystery," and "Rhapsody on Returning to the Fields." The last one mixes Daoist ideas with Confucianism. According to Liu Wu-chi, it was an early example of Chinese nature poetry. A group of four short poems (shi) called "Lyric Poems on Four Sorrows" is also included. These are some of the earliest Chinese poems written with seven characters per line.

While in Luoyang, Zhang was inspired to write his "Western Metropolis Rhapsody" and "Eastern Metropolis Rhapsody." These were based on a poem by the historian Ban Gu. Zhang's work was similar to Ban's. However, Ban's poem praised the current Eastern Han government. Zhang's poem warned that the Eastern Han could end up like the Western Han. He suggested this could happen if it became too luxurious and corrupt. These two works made fun of and criticized what he saw as the rich lifestyle of the upper classes. Zhang's "Southern Capital Rhapsody" celebrated his home city of Nanyang. This city was where the Han Dynasty was restored.

In his poem "Stabilizing the Passions," Zhang showed his admiration for a beautiful and good woman. This simpler type of fu poem influenced later works. These included poems by the important scholar Cai Yong. Zhang wrote:

|

夫何妖女之淑麗 |

Ah, the pure beauty of this charming woman! |

Zhang's long poems also shared a lot of information about city layouts and geography. His poem "Sir Based-On-Nothing" describes the land, palaces, hunting parks, markets, and buildings of Chang'an. This was the capital of the Western Han. He paid close attention to details. For example, his poem about Nanyang described gardens. These gardens had spring garlic, summer bamboo shoots, autumn leeks, and winter rape-turnips. They also had perilla, evodia, and purple ginger. Zhang Heng's writing confirms the size of the imperial hunting park. His estimate for the wall around the park matches the historian Ban Gu's. It was about 400 li (about 166 km or 103 miles). Zhang listed many animals and hunting games in the park. These were divided by where they came from: northern or southern China. Zhang described the Western Han emperors enjoying boat trips, water games, fishing, and archery. They shot arrows at birds and animals from tall towers near Chang'an's Kunming Lake. Zhang's focus on specific places, their land, people, and customs can be seen as early attempts at ethnographic studies. In his poem "Xijing fu," Zhang showed he knew about the new foreign religion of Buddhism. It was brought to China by the Silk Road. He also knew the story of Buddha's birth, with the vision of a white elephant. In his "Western Metropolis Rhapsody," Zhang described court shows. These included juedi, a type of wrestling with music. Wrestlers wore bull horn masks and butted heads.

Zhang was an early writer of a Chinese literary style called shelun, or hypothetical discourse. His work "Responding to Criticism" was based on Yang Xiong's "Justification Against Ridicule." In this style, authors write a conversation between themselves and an imaginary person. This person asks the author how to live a successful life. Zhang also used it to criticize himself for not getting a high government job. But he concluded that a true gentleman shows virtue, not a desire for power. Dominik Declercq suggests that the person urging Zhang to advance his career probably represented powerful groups. These groups might have been the eunuchs or Empress Liang's relatives. Declercq says these groups wanted to know if Zhang could be convinced to join their side. But Zhang clearly refused. He stated in his writing that his search for virtue was more important than any desire for power.

Zhang's writings often criticized the Eastern Han emperors. He did this by criticizing earlier Western Han emperors. Besides their lavish spending, Zhang also said their actions did not follow the Chinese beliefs in yin and yang. In a poem criticizing the Western Han Dynasty, Zhang wrote:

|

得之者強, |

Those who won this land were strong; |

Zhang Heng's Scientific and Technical Achievements

How Zhang Heng Improved Mathematics

For many centuries, the Chinese used 3 as an estimate for pi. Liu Xin (died 23 AD) made the first known Chinese attempt at a more accurate calculation. He found it to be 3.1457, but we don't know how he did it. Around 130 AD, Zhang Heng compared the circle of the sky to the Earth's diameter. He used a ratio of 736 to 232, which calculated pi as 3.1724. In Zhang's time, the area of a square to its inscribed circle was thought to be 4:3. For a cube and its inscribed sphere, it was 42:32. Zhang realized this was not accurate. He tried to fix it by adding a small correction to the formula. From this, Zhang calculated pi as the square root of 10 (about 3.162). Zhang also calculated pi as  = 3.1466 in his book Ling Xian. Later, in the 3rd century, Liu Hui made the calculation even more accurate. He found pi to be 3.14159. Even later, Zu Chongzhi (429–500) got pi to be

= 3.1466 in his book Ling Xian. Later, in the 3rd century, Liu Hui made the calculation even more accurate. He found pi to be 3.14159. Even later, Zu Chongzhi (429–500) got pi to be  or 3.141592. This was the most accurate calculation in ancient China.

or 3.141592. This was the most accurate calculation in ancient China.

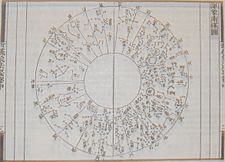

Zhang Heng's Astronomy Discoveries

In his book The Spiritual Constitution of the Universe (120 AD), Zhang Heng had a theory about the universe. He thought it was like an egg, "as round as a crossbow pellet." The stars were on the shell, and the Earth was the yolk in the middle. This idea is similar to the geocentric model, where Earth is the center. Earlier Chinese astronomers had already made China's first star catalogue. But Zhang still listed 2,500 stars that he called "brightly shining." He also recognized 124 constellations. His star catalog had many more stars than the 850 listed by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus. It also had more than Ptolemy's 1,000 stars.

Zhang believed in the "radiating influence" theory for solar and lunar eclipses. This theory was opposed by Wang Chong. In his book Ling Xian, Zhang wrote:

夫日譬猶火,月譬猶水,火則外光,水則含景。故月光生於日之所照,魄生於日之所蔽,當日則光盈,就日則光盡也。

The Sun is like fire, and the Moon is like water. Fire gives off light, and water reflects it. So the Moon's brightness comes from the Sun's light. The Moon's darkness is because the Sun's light is blocked. When the Moon faces the Sun, it is fully lit. When it is near the Sun, its light is gone.

衆星被燿,因水轉光。當日之衝,光常不合者,蔽於地也。是謂闇虛。在星星微,月過則食。

The planets (and the Moon) are like water and reflect light. The light from the Sun does not always reach the Moon. This is because the Earth blocks it. This is called "ànxū", a lunar eclipse. When something similar happens with a planet, we call it an occultation. When the Moon passes in front of the Sun, there is a solar eclipse.

Zhang Heng also saw these sky events in a spiritual way. He believed that comets, eclipses, and planet movements could guide how the government should act. Other writers at the time also wrote about eclipses and how heavenly bodies were round.

Zhang's theory was supported by later scientists like Shen Kuo. He explained more about why the Sun and Moon are round. The idea of a celestial sphere around a flat, square Earth was later criticized. The scholar Yu Xi suggested that the Earth could be round like the heavens. This spherical Earth theory was fully accepted by mathematician Li Ye. However, it was not widely accepted in Chinese science until European ideas arrived in the 17th century.

Zhang Heng's Water Clock Improvement

The outflow clepsydra (water clock) was used in China as early as the Shang Dynasty. The inflow clepsydra, with a floating indicator rod, was known since the start of the Han Dynasty (202 BC). It replaced the outflow type. The Han Chinese noticed a problem: the water pressure in the tank would drop. This made the clock slow down as the water level went down. Zhang Heng was the first to fix this problem. In his writings from 117 AD, he described adding an extra tank. This tank was placed between the main water supply and the clock's vessel.

Zhang also put two small statues on top of the inflow clepsydra. One was a Chinese immortal, and the other was a heavenly guard. They would hold the indicator rod with their left hands. With their right hands, they would point to the time marks. Joseph Needham believes this might have been the start of "clock jacks." These are figures that move and strike the hours in later mechanical clocks. However, Zhang's figures did not actually move or make sounds. Many more tanks were added to later water clocks, following Zhang Heng's idea. In 610 AD, engineers Geng Xun and Yuwen Kai made a special balance. It could adjust the water flow for different day and night lengths throughout the year. Zhang mentioned a "jade dragon's neck," which later meant a siphon. He wrote about the floats and indicator-rods of the inflow clepsydra:

以銅為器,再疊差置,實以清水,下各開孔,以玉虯吐漏水入兩壺。右為夜,左為晝。

Bronze vessels are made and placed one above the other at different levels. They are filled with pure water. Each has a small opening at the bottom, shaped like a 'jade dragon's neck'. The water dripping (from above) enters two inflow receivers (one after the other). The right one is for the night, and the left one is for the day.

蓋上又鑄金銅仙人,居左壺;為胥徒,居右壺。皆以左手抱箭,右手指刻,以別天時早晚。

On the covers of each (inflow receiver) are small statues made of gilt bronze. The left (night) one is an immortal, and the right (day) one is a policeman. These figures guide the indicator-rod (like an arrow) with their left hands. They point to the time marks with their right hands, showing the time of day or night.

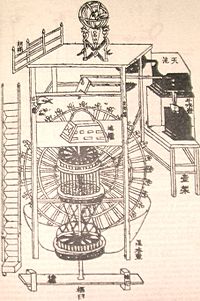

Zhang Heng's Water-Powered Armillary Sphere

Zhang Heng was the first person known to use water power to turn an armillary sphere. This is an astronomy tool that shows the celestial sphere (the imaginary sphere where stars appear). The Greek astronomer Eratosthenes invented the first armillary sphere in 255 BC. The Chinese armillary sphere was fully developed by 52 BC. The astronomer Geng Shouchang added a fixed equatorial ring. In 84 AD, astronomers Fu An and Jia Kui added the ecliptic ring. Finally, Zhang Heng added the horizon and meridian rings.

Zhang's invention is described in old writings. It was likely part of his book Hun I or Hun I Thu Chu, written in 117 AD. His water-powered armillary sphere influenced later Chinese water clocks. It also led to the discovery of the escapement mechanism in the 8th century.

Zhang did not start the Chinese tradition of hydraulic engineering. This began much earlier, around the 6th century BC. Zhang's contemporary, Du Shi, was the first to use waterwheels to power the bellows of a blast furnace. This was used to make pig iron and cast iron.

Zhang Heng's water-powered armillary sphere had a big impact on Chinese astronomy and mechanical engineering. His design and its complex gears influenced later astronomers. These included Yi Xing, Zhang Sixun, Su Song, and Guo Shoujing. Water-powered armillary spheres based on Zhang Heng's design were used in later dynasties. However, the design was lost for a while between 317 and 418 AD due to invasions. Zhang Heng's old instruments were found again in 418 AD. This was when Emperor Wu of Liu Song captured the old capital of Chang'an. The instruments were still there, but the marks and images were worn out. In 436 AD, the emperor ordered Qian Luozhi to rebuild Zhang's device. Qian successfully did it. Qian's water-powered celestial globe was still used during the Liang Dynasty. New models of water-powered armillary spheres were designed in later dynasties.

Zhang Heng's Seismoscope

From very early times, the Chinese worried about earthquakes. It was recorded that in 780 BC, an earthquake was strong enough to change the path of three rivers. People at the time didn't know that earthquakes were caused by shifting tectonic plates. Instead, people in the ancient Zhou Dynasty thought they were caused by problems with cosmic yin and yang. They also believed they were a sign of Heaven's unhappiness with the ruler or if people's complaints were ignored. These ideas came from the ancient book Yijing. Other early theories about earthquakes existed. For example, Aristotle thought they were caused by unstable vapor from the drying Earth.

During the Han Dynasty, many scholars, including Zhang Heng, believed in "oracles of the winds." These oracles observed the wind's direction, strength, and timing. They used this to guess how the universe worked and to predict events on Earth. These ideas influenced Zhang Heng's thoughts on what caused earthquakes.

In 132 AD, Zhang Heng showed the Han court what many historians consider his most amazing invention. It was the first seismoscope. A seismoscope records Earth's shaking. But unlike a seismometer, it doesn't keep a time record of the movements. It was called the "earthquake weathervane" (hòufēng dìdòngyí). It could roughly tell the direction (out of eight directions) where an earthquake came from. According to the Book of Later Han, his bronze, urn-shaped device had a swinging pendulum inside. It could detect the direction of an earthquake hundreds of miles away. This was very important for the Han government. It helped them send quick help to areas hit by natural disasters. The Book of Later Han says that one time, Zhang's device was triggered. But no one in the capital felt any shaking. Several days later, a messenger arrived from the west. He reported that an earthquake had happened in Longxi (modern Gansu Province). This was the same direction Zhang's device had shown. So, the court had to admit the device worked well.

To show the direction of a distant earthquake, Zhang's device dropped a bronze ball. This ball came from one of eight dragon heads. Each head was a tube. The ball fell into the mouth of a metal toad below. Each toad represented a direction, like points on a compass rose. His device had eight moving arms (for all eight directions). These were connected to cranks with special catch mechanisms. When triggered, a crank and a lever would lift a dragon head. This released a ball that was held by the dragon's lower jaw. His device also had a vertical pin, a catch, a pivot, and a sling holding the pendulum. Wang Zhenduo argued that the technology of the Eastern Han era was advanced enough to build such a device. This was shown by the levers and cranks used in other devices like crossbow triggers.

Later Chinese people were able to recreate Zhang's seismoscope. These included the mathematician Xindu Fang in the 6th century and the astronomer Lin Xiaogong in the 7th century. Like Zhang, they received support from the emperor for their inventions. By the time of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), it was known that all previous devices were saved, except for the seismoscope. The scholar Zhou Mi discussed this around 1290. He noted that the books by Xindu Fang and Lin Xiaogong describing their seismological devices were lost. Some historians wonder if Tang Dynasty seismographs made their way to Japan.

Hong-sen Yan says that modern copies of Zhang's device have not been as accurate as described in historical records. Wang Zhenduo showed two different models of the seismoscope. These were based on old descriptions of Zhang's device. In his 1936 model, the central pillar was a hanging pendulum. In his 1963 model, it was an inverted pendulum. According to Needham, Akitsune Imamura and Hagiwara rebuilt Zhang's device in 1939. Imamura was the first to suggest an inverted pendulum model. He argued that a side shock would make Wang's design ineffective. It would not stop other balls from falling out. On June 13, 2005, modern Chinese seismologists announced they had successfully made a working copy of the instrument.

Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, a professor of Chinese history, says Zhang Heng was one of several high-ranking officials who worked on crafts. These crafts were usually done by artisans. Barbieri-Low thinks Zhang only designed his seismoscope. He probably didn't build it himself. He believes artisans hired by Zhang would have done the actual building. He writes that Zhang was an important official. He would not have been seen working in the workshops with artisans and government slaves. He likely worked with the professional casters and mold makers in the imperial workshops.

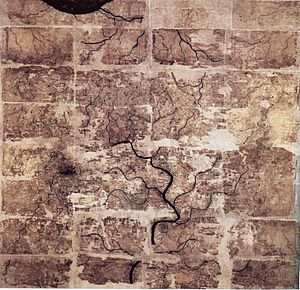

Zhang Heng's Cartography (Map-Making) Work

The Wei and Jin Dynasty (266–420) mapmaker Pei Xiu was the first in China to fully describe the geometric grid reference for maps. This allowed for exact measurements using a scale. It also showed elevation. However, map-making in China had existed since at least the 4th century BC. This is shown by Qin state maps found in 1986. Accurate maps of winding rivers and scaled distances were known since the Qin and Han Dynasty. The use of a rectangular grid was also known in China since the Han. Historian Howard Nelson says that Zhang Heng's work in map-making is not fully clear. But there is enough written proof that Pei Xiu got the idea of the rectangular grid from Zhang Heng's maps. Rafe de Crespigny states that Zhang was the one who created the rectangular grid system in Chinese map-making. Needham points out that the title of Zhang's book Flying Bird Calendar might be a mistake. He thinks the book is more accurately called Bird's Eye Map. Historian Florian C. Reiter notes that Zhang's story "Guitian fu" mentions praising the maps and documents of Confucius. Reiter suggests this means maps were as important as documents. It is recorded that Zhang Heng first presented a physical geography map in 116 AD. It was called a Ti Hsing Thu.

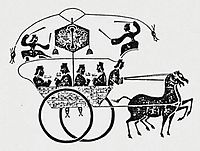

Zhang Heng's Odometer and South-Pointing Chariot

Zhang Heng is often given credit for inventing the first odometer. This device measures how far something travels. Similar devices were used by the Roman and Han-Chinese empires around the same time. By the 3rd century, the Chinese called the device the jili guche. This means "li-recording drum carriage" (a li is about 500 meters or 1640 feet).

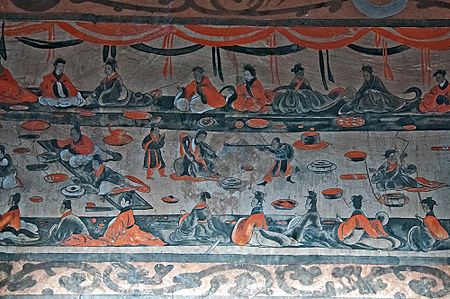

Ancient Chinese texts describe how the mechanical carriage worked. After one li was traveled, a wooden figure would strike a drum. After ten li, another wooden figure would strike a gong or a bell. However, there is evidence that the odometer was invented gradually in Han Dynasty China. It was linked to court people who followed the royal "drum-chariot" musical procession. Some think that around the 1st century BC, the drums and gongs were mechanically hit by the turning of the wheels. This might have been designed by Luoxia Hong. But by at least 125 AD, the mechanical odometer carriage was known. It was shown in a mural in the Xiao Tang Shan Tomb.

The south-pointing chariot was another mechanical device credited to Zhang Heng. It was a non-magnetic compass vehicle. It was a two-wheeled chariot. Differential gears were driven by the chariot's wheels. These gears allowed a wooden figure to always point to the south. That's how it got its name. The Song Shu (around 500 AD) says that Zhang Heng reinvented it. It was based on a model used in the Zhou Dynasty. But the fall of the Han Dynasty meant it was not saved. Whether Zhang Heng invented it or not, Ma Jun successfully built the chariot in the next century.

Zhang Heng's Legacy

Impact on Science and Technology

Zhang Heng's mechanical inventions influenced later Chinese inventors. These included Yi Xing, Zhang Sixun, Su Song, and Guo Shoujing. Su Song directly said that Zhang's water-powered armillary sphere inspired his 11th-century clock tower. The idea of nine points of Heaven matching nine regions of Earth came from Zhang's book Spiritual Constitution of the Universe. The seismologist John Milne, who created the modern seismograph in 1876, praised Zhang Heng's work in seismology. The historian Joseph Needham highlighted Zhang's contributions to early Chinese technology. He said Zhang was known for being able to "make three wheels rotate as if they were one." Many scholars describe Zhang as a polymath, meaning he was skilled in many areas. However, some scholars also note that Zhang's writings don't have very specific scientific theories. Comparing Zhang to his contemporary, Ptolemy, scholars Jin Guantao, Fan Hongye, and Liu Qingfeng state:

-

- Zhang Heng developed the celestial sphere theory based on earlier ideas. An armillary sphere built using his ideas is very similar to Ptolemy's Earth-centered theory. However, Zhang Heng did not clearly propose a theoretical model like Ptolemy's. It's amazing that the celestial model Zhang Heng built was almost a physical model of Ptolemy's Earth-centered theory. Only one step separates the celestial globe from the Earth-centered theory, but Chinese astronomers never took that step.

-

- This shows how important early scientific structures are. To use the Euclidean system of geometry for astronomy, Ptolemy first chose ideas that could be basic rules. He naturally saw circular motion as key. Then he used the circular motion of deferents and epicycles in his Earth-centered theory. Even though Zhang Heng understood that the sun, moon, and planets move in circles, he lacked a model for a logical theory. So, he couldn't create a matching astronomy theory. Chinese astronomy was most interested in finding the math patterns of planet motion (like how long cycles lasted). This made astronomy more about math calculations. It involved finding common multiples and divisors from observed movements of heavenly bodies.

Impact on Poetic Literature

Zhang's poetry was widely read during his life and after his death. Besides the collection by Xiao Tong, the official Xue Zong wrote comments on Zhang's poems "Dongjing fu" and "Xijing fu." The important poet Tao Qian admired Zhang Heng's poetry. He said it "curbed extravagant diction and aimed at simplicity." He felt Zhang's simple language showed calmness and honesty. Tao wrote that both Zhang Heng and Cai Yong "avoided fancy language, aiming mainly for simplicity." He added that their "writings start by freely expressing their ideas but end calmly. They are excellent at controlling wild and emotional feelings."

Honors After Death

Zhang received great honors both during his life and after his death. The philosopher Fu Xuan (217–278) once wrote an essay regretting that Zhang Heng was never placed in the Ministry of Works. He praised Zhang and the 3rd-century engineer Ma Jun. Fu Xuan wrote, "Neither of them was ever an official of the Ministry of Works. Their cleverness did not help the world. When authorities hire people without caring about special talent, and hear of genius but don't even test it—isn't this terrible and harmful?"

To honor Zhang's achievements in science and technology, his friend Cui Ziyu wrote a memorial inscription for his tombstone. This inscription has been saved. Cui stated, "[Zhang Heng's] math calculations solved the mysteries of the heavens and the earth. His inventions were even as good as those of the Author of Change. His amazing talent and the beauty of his art were like those of the gods." The official Xiahou Zhan (243–291) wrote an inscription for his own tombstone. He wanted it placed at Zhang Heng's tomb. It read: "Since gentlemen have written literary texts, none has been as skilled as the Master [Zhang Heng] in choosing his words well... if only the dead could rise, oh I could then turn to him for a teacher!"

Several things have been named after Zhang in modern times. These include the lunar crater Chang Heng, the asteroid 1802 Zhang Heng, and the mineral zhanghengite. In 2018, China launched a research satellite called the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite (CSES). It is also named Zhangheng-1 (ZH-1).

See also

In Spanish: Zhang Heng para niños

In Spanish: Zhang Heng para niños

- Han poetry

- Fu (poetry)

- Return to the Field

- Yu Xi

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |