South-pointing chariot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids South-pointing chariot |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 指南車 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 指南车 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | xe chỉ nam chỉ nam xa |

||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 車指南 指南車 |

||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||

| Hangul | 지남차 | ||||||||||||

| Hanja | 指南車 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

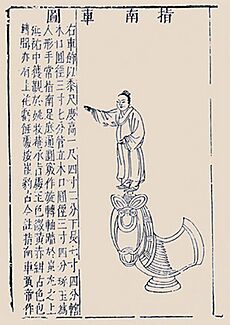

Imagine a special ancient Chinese cart that always pointed south! This was the south-pointing chariot. It was a two-wheeled vehicle with a moving pointer. This pointer, often a small doll or figure, always aimed south, no matter which way the chariot turned. People believed it helped with navigation, like a compass.

Long ago, around 500 BC, the Chinese had armored carts called Dongwu Che. These carts protected soldiers in battles. They were like mobile shelters with roofs. Soldiers would roll them up to city walls to dig safely underneath. These early war wagons might have inspired the idea for the south-pointing chariots.

While there are old stories about even earlier south-pointing chariots, the first one we know for sure was built by a clever Chinese engineer named Ma Jun. He lived around 200-265 AD during the Three Kingdoms period. None of these ancient chariots still exist today. However, many old Chinese writings talk about them. They say these chariots were used on and off until about the year 1300. Some texts even describe how they worked inside.

There were probably different kinds of south-pointing chariots. Most of them used a system of gears. These gears were connected to the chariot's wheels. When the wheels turned, the gears made sure the pointer stayed aimed correctly. The chariots did not use magnets to find south. Instead, someone would point the doll south at the start of a journey. Then, as the chariot moved and turned, the gears would spin the pointer. This kept it facing the same direction, always south. This system was a bit like "dead reckoning," which means figuring out your position based on where you started and how you moved. Because of this, small errors could add up over time. Some chariots might have even used special differential gears.

Contents

How Did Ancient Texts Describe These Chariots?

Early Mentions of the South-Pointing Chariot

One of the first people to write about the south-pointing chariot was Fu Xuan, who lived at the same time as Ma Jun. Another 3rd-century book, the Weilüe, also described Ma Jun's chariot. Later, a book from the Jin dynasty (266–420) called Shu Zheng Ji said that south-pointing chariots were often kept in the capital city's workshops.

However, the Song Shu (written in the 6th century) gave more details. It even told a legend that the chariot was used much earlier, during the Western Zhou dynasty (1050–771 BC). The book also described how the chariot was "re-invented" and used after Ma Jun's time.

Here's a part of what the 6th-century text said, translated by historian Joseph Needham:

The south-pointing carriage was first built by the Duke of Zhou (around 1000 BC). It helped visitors from far away find their way home. Their land was a huge plain where people easily got lost. So, the Duke made this vehicle to help them tell north from south. The Gui Gu Zi book says that people from the State of Zheng always carried a 'south-pointer' when collecting jade. This way, they never got lost. During the Qin and Former Han dynasties, people didn't hear about this vehicle anymore. In the Later Han period, Zhang Heng re-invented it. But it was lost during the chaos at the end of that dynasty.

In the State of Wei, scholars Gaotong Long and Qin Lang argued that the south-pointing carriage wasn't real. But during the Qing-long period (233–237), Emperor Ming Di asked Ma Jun to build one, and he succeeded! This one was also lost later during the start of the Jin dynasty.

Later, Shi Hu (an emperor) had one made by Xie Fei. Then Linghu Sheng made one for Yao Xing (another emperor). This chariot ended up with Emperor An Di of the Jin in 417 AD. Finally, Emperor Wu Di of the Liu Song dynasty got it. It looked like a drum-carriage (odometer). A wooden figure on top had its arm pointing south. Even when the carriage turned, the arm still pointed south. In parades, the south-pointing carriage led the way with the imperial guard.

These vehicles, made by foreign workers, didn't always work perfectly. They were called south-pointing carriages, but often didn't point true. Someone inside had to adjust the machine step by step. A smart man named Zu Chongzhi often said a new, truly automatic south-pointing carriage should be built. So, around 477–479 AD, Emperor Shun Di asked Zu Chongzhi to make one. When it was done, it was tested and worked perfectly. Even when the carriage twisted and turned many times, the hand always pointed south. The Jin dynasty also had a south-pointing ship.

The last sentence about a "south-pointing ship" is interesting! This was long before the magnetic compass was used for sea travel, which happened around the 11th century. Even though the Song Shu text talks about earlier chariots, it's not fully believable. There are no writings from before the Han dynasty that describe this device. The first known source to mention these legends was the Gu Jin Zhu (around 300 AD).

South-Pointing Chariots in Japan

The idea of the south-pointing chariot also reached Japan by the 7th century. The Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan), written in 720 AD, says that Chinese Buddhist monks named Zhi Yu and Zhi You built several south-pointing chariots for Emperor Tenji of Japan in 658 AD. More chariots were built in 666 AD.

The Song Shi and Later Designs

The south-pointing chariot was sometimes combined with another invention: the odometer. An odometer is a device that measures how far you've traveled, like the one in modern automobiles. The Song Shi (a historical text from the Song dynasty compiled in 1345) mentions that engineers Yan Su (in 1027) and Wu Deren (in 1107) both built south-pointing chariots.

Here's a simplified look at Yan Su's design:

In 1027, Yan Su, an official, made a south-pointing carriage. He told the emperor that no one had been able to build one since the Five Dynasties period. But he had invented a new design and finished it.

His carriage had one pole for two horses. On top, there was a cover with two levels. A wooden figure of an xian (an immortal being) was placed at the top, pointing south. The machine used 9 wheels, big and small, with 120 teeth in total. There were two road-wheels (the main wheels the carriage runs on), each 6 feet high. Connected to these were two smaller vertical wheels, each with 24 teeth.

Below the pole, there were two small vertical wheels. To the left and right were small horizontal wheels, each with 12 teeth. In the middle was a large horizontal wheel, 4.8 feet across, with 48 teeth. A vertical shaft went through the center of this large wheel, 8 feet high, and held the wooden xian figure at its top.

When the carriage moved south, the figure pointed south. If it turned east, the right road-wheel would turn, making the right small horizontal wheel spin. This would turn the central large horizontal wheel a quarter turn to the left. The figure would then stand sideways but still point south. If it turned west, the left road-wheel would turn, spinning the left small horizontal wheel. This would turn the central large horizontal wheel a quarter turn to the right. Again, the figure would stand sideways but still point south. Traveling north involved similar turns.

After describing Yan Su's chariot, the text talks about Wu Deren. He built a vehicle that combined both the odometer and the south-pointing chariot.

Chariots with Differential Gears: A Modern Idea?

What is a Differential Gear?

An English engineer named George Lanchester suggested that some south-pointing chariots used differential gears. A differential is a set of gears found in most modern cars. It has three shafts. One shaft connects to the engine, and the other two connect to the car's wheels.

When a car turns, the wheel on the outside of the turn has to travel farther and spin faster than the wheel on the inside. The differential allows this to happen while both wheels are still powered by the engine.

In a south-pointing chariot, if it had a differential, one wheel would connect to one side of the differential. The other wheel would connect to the other side, but through a gear that reversed its direction. This setup would make a central shaft spin based on the *difference* in speed between the two wheels. The pointing doll would be connected to this central shaft.

When the chariot went straight, both wheels spun at the same speed. So, the doll wouldn't move. But when the chariot turned, the wheels spun at different speeds. The differential would then make the doll rotate, canceling out the chariot's turn and keeping the doll pointed south.

The idea that these chariots used differential gears came about in the 20th century. People who knew about modern differentials looked at the old Chinese descriptions and thought they matched. It's like they "re-invented" the chariot, just as it was re-invented many times in ancient China. Working models of south-pointing chariots using differentials have been built recently. But we don't know for sure if ancient chariots actually used them.

The Antikythera mechanism, an ancient Greek device, is thought to have used differential gears. However, the first time we know for sure a differential gear was used was by Joseph Williamson in 1720. He used it in a clock to show both average time and actual solar time.

Why Precision Matters (or Doesn't)

If a south-pointing chariot with a differential gear was built perfectly, it would be a mechanical compass that could "carry" a direction along its path. It would perform something called "parallel transport" in mathematics.

However, real machines are never perfect. If the chariot's wheels were supposed to be identical but differed in size by even a tiny bit (like one part in a thousand), the pointer would drift. For example, if it traveled one kilometer in a straight line, the pointer could turn almost twenty degrees! This would make it useless as a compass for long journeys. To be truly useful, the wheels would need to be almost perfectly equal in size, which was impossible with ancient methods. Also, rough ground would add more errors.

So, it's hard to believe these chariots were used for long-distance navigation if they relied only on differential gears. Maybe the pointing doll was only connected to the differential when the chariot was turning. The driver could have connected and disconnected it. This would reduce errors, but then how would the chariot stay straight without the doll?

Perhaps the main purpose of these chariots was for fun or to impress visitors, not for actual navigation. They were complex and fragile, and they were "re-invented" many times. This suggests they weren't practical navigation tools that people would use all the time.

Chariots Without Differential Gears

Even though the differential gear idea is popular, it's possible that some south-pointing chariots worked without them. The old descriptions are often unclear, but they hint that the Chinese tried several different designs.

Other Mechanical Designs

Some descriptions suggest that certain chariots could only move in three ways: straight, or turning left or right with a set turning circle. A third wheel might have been used to control the turning radius. When the chariot turned, the pointing doll would connect to one of the main road wheels. This would make the doll spin at a set speed to balance the chariot's turn. This design would have been simpler than using a differential gear.

The chariots built by Yan Su and Wu Deren seem to have used this kind of system. (You can see parts of their descriptions above.) When the chariot went straight, the gears weren't connected. But when it turned, a small gear would drop down. This connected the doll to one of the road wheels. There were two small gears, one for left turns and one for right turns. They were raised and lowered automatically by weights and cords connected to the pole the horses pulled. When the horses moved to turn, the pole moved, and the correct small gear dropped into place. When the horses went straight again, the gear lifted. This made the system automatic.

This design could have worked quite well for short trips in good conditions. But for long journeys, errors would still build up.

If there was no third wheel, the chariot might have worked if turns were always made so that one wheel stopped completely while the other rotated. The driver would have to be very skilled to do this. This would have made turns slow and awkward. But if turns were rare, it might not have mattered.

The Song Shi description of Yan Su's chariot suggests it worked this way, without a third wheel. The gear sizes would have been correct if the doll was directly attached to the large horizontal gear, and the chariot's width matched the road wheel's diameter. Wu Deren's chariot also seems to have been designed this way.

A skilled driver could have made the chariot *seem* very accurate, especially if demonstrating it to people. They could have adjusted the turns to make the doll point south perfectly. This might have impressed people and brought fame to the builders, even if the chariots weren't truly reliable for long-distance navigation.

Other mechanical designs are possible, even using a gyrocompass, but there's no sign the ancient Chinese knew about these.

Could Non-Mechanical Methods Have Been Used?

Some south-pointing chariots might not have been purely mechanical. Someone riding inside could have used other ways to find directions and then manually turned the doll. Here are some ways they could have done it:

- Using a magnetic compass: The Chinese were using magnetic compasses for navigation by the 11th century, when these chariots were still being made.

- Looking at the sky: They could have used the Sun or stars, like the Pole Star. The Chinese had a lot of knowledge about astronomy.

- Local knowledge: The person inside might have known the area well or had a map.

- Observing light: Vikings used special crystals to navigate by looking at how light from the sky was polarized. This is possible in China too.

- Refracted light: Polynesian sailors used techniques to see things far away by how light bends in the atmosphere. Some of these techniques could also be used on land.

Unlike mechanical systems, most of these methods work at sea. This might explain the mention of a "south-pointing ship." These methods can also be accurate over long distances, unlike the mechanical designs.

Why Was Initial Setup Important?

Any south-pointing chariot needed to be "initialized" at the start of a journey. This means someone had to aim its pointer exactly south. They could have used any of the non-mechanical methods mentioned above.

If a south-pointing chariot was truly used for long-distance travel, it must have relied on a non-mechanical way to find direction after it started moving. Or, if it had a mechanical system, it would need to be reset often to fix any errors that built up.

The only chariots that wouldn't need non-mechanical methods were those used just for fun or to trick people. In those cases, they could just pick any direction and call it "south."

Modern Replicas of the Chariot

While the original chariots are gone, you can find full-sized replicas today.

The History Museum in Beijing, China, has a replica based on Yan Su's design from 1027. The National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan, has one based on Lanchester's differential mechanism from 1932.

At the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto, Canada, you can see and even try out two replicas, sometimes called "southern pointing men."

See also

- Chariots in ancient China

- Chinese war wagon

- History of science and technology in China

- List of Chinese inventions

- Mechanical engineering

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |