Joseph Needham facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

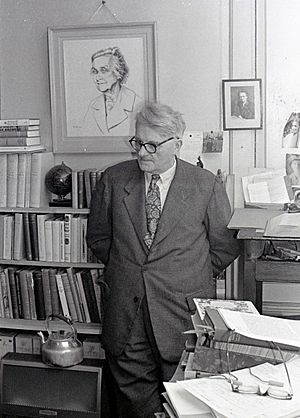

Joseph Needham

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||

| Born |

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham

9 December 1900 London, England

|

||||||||

| Died | March 24, 1995 (aged 94) Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England

|

||||||||

| Alma mater | Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge (BA, MA, PhD) | ||||||||

| Occupation | Biochemist, historian of science, sinologist | ||||||||

| Known for | Science and Civilisation in China | ||||||||

| Spouse(s) | |||||||||

| Awards | Leonardo da Vinci Medal (1968) Dexter Award (1979) |

||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 李約瑟 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 李约瑟 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Li (surname 李) Joseph | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

Joseph Needham (born December 9, 1900 – died March 24, 1995) was a brilliant British scientist and historian. He was a biochemist, which means he studied the chemistry of living things. He was also a historian of science, meaning he studied how science has changed over time.

Needham is most famous for his huge project called Science and Civilisation in China. This multi-volume book series explored the amazing history of Chinese science and technology. He wanted to understand why China, which was very advanced for centuries, was later overtaken by Western countries in science and technology. This question is now known as the "Needham Question."

He received many honors for his work. He was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1941 and the British Academy in 1971. In 1992, Queen Elizabeth II gave him the Order of the Companions of Honour, a very special award.

Contents

Early Life and School

Joseph Needham's father was a doctor, and his mother, Alicia Adelaïde, was a music composer. His father worked hard to become a successful doctor in London. Joseph often helped his parents when they argued.

When he was young, Joseph was inspired by lectures from a mathematician named Ernest Barnes. Barnes taught him about philosophers and medieval thinkers. This helped Joseph develop a strong Christian faith and an open mind about other cultures' religions.

In 1914, when World War I started, Joseph went to Oundle School. He didn't like leaving home, but he admired the headmaster, Frederick William Sanderson. Sanderson focused on science and technology, even having a metal shop. This gave Joseph a good start in engineering. Sanderson also taught students that working together was better than competing. He believed that knowing history was key to building a better future.

During school breaks, Joseph helped his father in hospitals during the war. This experience showed him he didn't want to be a surgeon.

Education and Early Career

In 1921, Joseph Needham earned his first degree from Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. He originally planned to study medicine. However, he met Frederick Hopkins, a famous scientist, and decided to switch to biochemistry. He earned his master's degree in 1925 and his PhD later that year.

After finishing his studies, Needham became a fellow at Gonville and Caius College. He worked in Hopkins' lab, focusing on embryology (the study of how living things develop before birth) and morphogenesis (how organisms get their shape).

In 1931, he published a three-volume work called Chemical Embryology. This book included a history of embryology from ancient times. Needham believed that understanding history was important for scientific progress. In 1936, he helped start the History of Science Committee at Cambridge.

Discovering China

Joseph Needham's life changed direction during and after World War II. In 1937, three Chinese scientists came to Cambridge to study. One of them, Lu Gwei-djen, was the daughter of a pharmacist from Nanjing. She taught Needham Chinese, which sparked his deep interest in China's ancient science and technology. He then learned Classical Chinese on his own.

From 1942 to 1946, Needham directed the Sino-British Science Co-operation Office in Chongqing, China. He traveled a lot through war-torn China, visiting scientific places and getting them much-needed supplies. On one long trip, he reached the Dunhuang caves, where the oldest dated printed book, the Diamond Sutra, was found.

Everywhere he went, he bought or was given old historical and scientific books. He sent these books back to Britain. They became the foundation for his future research. He met many Chinese scholars, including the artist Wu Zuoren and the meteorologist Zhu Kezhen. Zhu Kezhen later sent him many books, including a huge encyclopedia about China's past.

UNESCO and Return to Cambridge

After returning to Europe, Joseph Needham helped create the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). He became the first head of its Natural Sciences Section in Paris. Needham strongly believed that science should be part of UNESCO's goals.

He thought UNESCO should help countries outside of Europe and America the most. He also wanted UNESCO to create a history of science that included contributions from Eastern nations, not just Western ones. He believed this would help bring different cultures together. This project, called The History of Scientific and Cultural Development of Mankind, involved hundreds of scholars and took many years to complete.

In 1948, Needham left UNESCO and returned to Cambridge. He continued his research on the history of Chinese science until he retired in 1990. He also became the Master (head) of Gonville and Caius College in 1965.

Science and Civilisation in China

In 1948, Needham suggested a book project to Cambridge University Press about Science and Civilisation in China. The project quickly grew to seven volumes and has continued to expand ever since. His first helper was a historian named Wang Ling.

They spent years listing every mechanical invention and idea from China. Many of these, like cast iron, the ploughshare, the stirrup, gunpowder, printing, the magnetic compass, and clockwork, were once thought to be Western inventions. The first volume came out in 1954.

The books were highly praised. Needham wrote fifteen volumes himself, and new volumes are still being published even after his death. The project is now guided by the Needham Research Institute.

The series covers many topics, including:

- Vol. I. Introductory Orientations (Introduction)

- Vol. II. History of Scientific Thought (How science was thought about)

- Vol. III. Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth (Math, astronomy, geography)

- Vol. IV. Physics and Physical Technology (Physics and inventions)

- Vol. V. Chemistry and Chemical Technology (Chemistry and chemical inventions)

- Vol. VI. Biology and Biological Technology (Biology and biological inventions)

- Vol. VII. The Social Background (How society affected science)

The Needham Question

"The Needham Question" asks: Why did modern science, with its focus on math and experiments, begin in the West during the time of Galileo, and not in China? China had been much better at using scientific knowledge for practical needs for many centuries.

Needham pointed out that Francis Bacon, a famous Western thinker, thought three inventions—paper and printing, gunpowder, and the magnetic compass—changed the world. Bacon didn't know these were all Chinese inventions. Needham's work helped set the record straight.

Needham believed that Confucianism and Taoism (Chinese philosophies) influenced Chinese scientific discoveries. He also thought Chinese science often spread ideas, while Western science focused more on new inventions. He found that China had a steady growth in science throughout its history. However, this was later overtaken by the rapid growth of modern science in Europe after the Renaissance.

Some scholars, like Nathan Sivin, a collaborator of Needham's, agree that Needham's work was huge. But they also suggest that asking "Why didn't China have the Scientific Revolution first?" is a difficult question to answer.

Several ideas try to explain the Needham Question:

- Lack of Property Rights: Some argue that in China, people didn't have strong rights to their inventions or property. The emperor could take discoveries for the government's use. This might have reduced the desire to innovate.

- Government Control: The Chinese Empire was very large and had strong central control. The government controlled many aspects of life, from trade to what people could wear. This might have limited individual creativity and new ideas. People were not encouraged to move or trade freely, which can slow down innovation.

- Focus on Experience vs. Experiment: According to Justin Lin, China relied on an "experience-based" way of inventing. This meant new ideas came from trial and error by many people. Europe, however, shifted to an "experiment-based" way, using scientific methods and controlled tests. This allowed for much faster progress.

- Social Incentives: In pre-modern China, the most respected career was working for the government as a civil servant. Talented people were more likely to pursue this path than scientific research. This meant less focus on scientific experiments.

- High-Level Equilibrium Trap: China had a very large population. While a big population can provide cheap labor, it can also strain resources like land. This meant there wasn't much extra wealth or resources to invest in new technologies or an industrial revolution. Europe, with a smaller population and more available land and resources, had more potential for industrial growth.

Political Views

Needham had strong political views. He was a Christian socialist, meaning he believed in combining Christian values with socialist ideas. He never joined the Communist Party. After 1949, he showed sympathy for China's new government.

During the Korean War, Needham investigated claims that the Americans used biological warfare. His report supported these claims, though it is still debated today whether the evidence was real or planted. Because of this, the US government did not allow Needham to visit the US until the 1970s.

In 1965, Needham helped create the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding. This group helped British people visit China. He believed China had a better government than before. However, he was saddened by the changes he saw during the Cultural Revolution in 1972.

Personal Life

Joseph Needham married biochemist Dorothy Moyle in 1924. They were the first married couple to both be elected as Fellows of the Royal Society.

Needham and Lu Gwei-djen, the Chinese scientist who taught him Chinese, fell in love. Dorothy accepted this, and the three of them lived near each other in Cambridge for many years. After Dorothy's death in 1987, Needham married Lu in 1989. She passed away two years later.

Needham suffered from Parkinson's disease starting in 1982 and died in 1995 at the age of 94.

In 2008, a special professorship at Cambridge University was named the Joseph Needham Professorship of Chinese History, Science, and Civilization in his honor. An annual lecture is also held in his memory.

Needham was a religious person, attending church regularly. He also called himself an "honorary Taoist" because of his deep respect for Chinese philosophy.

Honors and Awards

- George Sarton Medal, 1961

- Master of Gonville and Caius College, 1966

- Dexter Award for Outstanding Achievement in the History of Chemistry, 1979

- J.D. Bernal Award, 1984

- Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize, 1990

- Order of the Companions of Honour, 1992

- Fellow of the British Academy, 1971

- Fellow of the Royal Society, 1941

The Needham Research Institute in Cambridge, which studies China's scientific history, was opened in 1985.

Works

Joseph Needham wrote many books and essays. Here are some of his important works:

- Chemical Embryology (1931)

- A History of Embryology (1934)

- Biochemistry and Morphogenesis (1942)

- Science and Civilisation in China (starting 1954) – his most famous work, still ongoing

- The Grand Titration: Science and Society in East and West (1969)

- The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China (5 volumes) (1980–95) – a shorter version by Colin Ronan

- The Genius of China (1986) – a one-volume summary by Robert Temple

Images for kids

-

Tang Fei-fan and Joseph Needham in Kunming, Yunnan 1944

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Needham para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Needham para niños

- List of sinologists

- List of historians

- Four Great Inventions

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |