History of printing in East Asia facts for kids

Printing in East Asia first started in China. It grew from a method called ink rubbing, where people pressed paper or cloth onto stone tablets with writing on them. This was happening around the 500s. A new type of printing, called mechanical woodblock printing, began in China during the 600s in the Tang dynasty. This method of printing spread all over East Asia.

In 1088, a Chinese inventor named Bi Sheng created an early form of movable type. He used pieces of clay and wood that could be moved around to form Chinese characters. This was written about by Shen Kuo in his book Dream Pool Essays. The first paper money printed with movable metal type to add special codes was made in 1161 during the Song dynasty. By the 1200s, movable metal type printing had spread to Korea. The world's oldest surviving book printed with movable metal type is from Korea, made in 1377.

Later, from the 1600s to the 1800s in Japan, many woodblock prints called ukiyo-e were made. These colorful prints became very popular and even influenced European art movements like Japonisme and Impressionism. European-style printing presses arrived in East Asia in the 1500s but weren't widely used at first. Much later, mechanical printing presses with some European ideas were adopted, but then even newer laser printing systems took over in the 1900s and 2000s.

Contents

How Woodblock Printing Works

In East Asia, there were two main ways to print: woodblock printing and movable type printing. In woodblock printing, ink is put onto words and pictures carved into a wooden board. Then, the board is pressed onto paper. With movable type, the printing surface is built using individual letter pieces, depending on what needs to be printed on each page. Woodblock printing was used in the East from the 700s, and movable metal type started around the 1100s.

Woodblock Printing in China

Printing is known as one of the Four Great Inventions of China, which means it was a very important invention that spread around the world.

Some old stories suggest that printing might have started even earlier. For example, in the 480s, a man named Gong Xuanyi claimed he had a magical "jade block" that could make words appear on paper without a brush. Historians think this might have been an early printing device, and Gong used it to amaze people.

Carved seals made of metal or stone, and large stone tablets with writing, probably gave people ideas for printing. In the Han dynasty, copies of important texts were carved onto stone tablets and put in public places like Luoyang. Students and scholars could then make copies by rubbing ink onto paper placed over the carvings. This method of making ink rubbings likely led to the invention of printing.

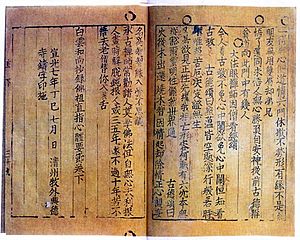

The oldest example of woodblock printing on paper was found in 1974 in Xi'an, China. It's a Buddhist prayer (dharani) printed on hemp paper, made between 650 and 670 AD during the Tang dynasty. Another old printed document, a Buddhist text called the Lotus Sutra, was printed between 690 and 699 AD. This was during the time of Empress Wu Zetian, who encouraged printing religious texts and images.

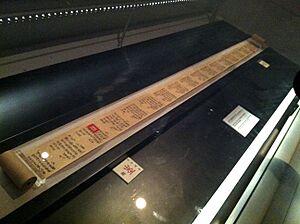

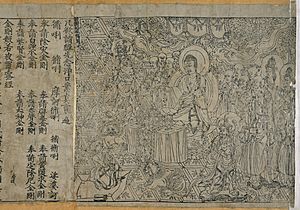

The oldest printed text with a specific date was found in the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang in 1907. It's a copy of the Diamond Sutra, which is 14 feet long. At the end, it says it was "Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong" (which means May 11, 868 AD). This makes it the oldest securely dated woodblock scroll in the world.

During the Song dynasty, from 960 to 1279, government offices used woodblock prints to share official versions of important books. They also printed histories, philosophy books, encyclopedias, and books on medicine and war. A huge project started in 971 to print the complete Buddhist Canon, called the Tripiṭaka. It took 10 years to carve 130,000 wooden blocks! The finished set, known as the Kaibao Tripitaka, was printed in 983.

How the Printing Process Worked

First, a professional writer copied the text onto thin, slightly waxy paper. The wax helped the ink transfer better. This paper was then placed ink-side down onto a wooden block that had a thin layer of rice paste on it. The back of the paper was rubbed with a brush, and the wet rice paste picked up some of the ink, leaving an impression on the wood.

Next, an engraver used sharp tools to carve away the parts of the woodblock that didn't have ink. This left the words and pictures raised, like a mirror image of the original writing. When carving, the knife was held like a small sword and guided by the other hand. Vertical lines were cut first, then the block was turned to cut horizontal lines.

The blocks were checked four times for mistakes. Small errors could be fixed by cutting out a tiny piece and hammering in a new wedge of wood. Bigger mistakes needed a larger piece of wood to be inserted. After carving, the block was washed clean.

To print, the block was held firmly on a table. The printer used a round brush to apply ink to the raised parts of the block. Then, paper was carefully placed on the inked block and rubbed with a special pad to transfer the image onto the paper. The paper was then peeled off and left to dry. Because of the rubbing, printing was only done on one side of the paper, which was thinner than Western paper. Usually, two pages were printed at once.

Sometimes, sample copies were made in red or blue, but black ink was always used for the final books. A skilled printer could make 1500 to 2000 double sheets in a single day! The wooden blocks could be stored and used again whenever more copies were needed. A single block could make 15,000 prints, and even more after a little touch-up.

Printing Spreads Across East Asia

Japan

In 764, Empress Kōken ordered one million small wooden pagodas (miniature temples), each with a tiny woodblock-printed scroll inside. These were given to temples across Japan as a thank you for stopping a rebellion. These are the earliest known examples of woodblock printing in Japan.

Later, in the Kamakura period (1100s to 1200s), many books were printed using woodblocks at Buddhist temples in Kyoto and Kamakura.

In the 1590s, Jesuit missionaries brought the movable-type printing press to Japan. This made people interested in printing Japanese books. From the 1600s, during the Edo period, books and pictures were mass-produced using woodblock printing and became popular among everyday people. This happened because Japan's economy grew, and many people learned to read. Almost all samurai could read, and about half of regular townspeople and farmers could too, thanks to many private schools.

In the city of Edo (now Tokyo), there were over 600 bookstores that rented out woodblock-printed books. These books covered many topics, like travel guides, gardening, cookbooks, funny stories, romance novels, and art books. Famous artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige created ukiyo-e prints, which showed popular subjects like kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, beautiful women, and landscapes. In the 1700s, Suzuki Harunobu developed a way to print with many colors, called nishiki-e, which made ukiyo-e even more amazing. These prints later influenced European art.

Korea

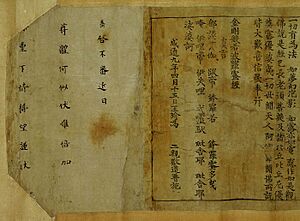

In Korea, an example of woodblock printing from the 700s was found in 1966. It's a Buddhist prayer called the Pure Light Dharani Sutra. It was discovered in a pagoda (a type of temple tower) in Gyeongju, South Korea, that was repaired in 751 AD. This means the print must have been made before that date, possibly as early as 704 AD. It was found inside the pagoda with many religious relics.

In 1011, King Hyeonjong of Goryeo ordered the carving of Korea's own set of Buddhist texts, which became known as the Goryeo Daejanggyeong. This huge project was finished in 1087, with about 6,000 volumes. Sadly, the original wooden blocks were destroyed during the Mongol invasion in 1232. King Gojong ordered a new set to be made, and it was completed in just 12 years, in 1248. This new Goryeo Daejanggyeong has 81,258 printing blocks carved on both sides, with over 52 million characters! It's considered the most accurate collection of Buddhist texts in Classical Chinese and is still kept in the Haeinsa temple today.

Printing Spreads to the Western World

The idea of printing moved from East Asia towards the Western world. In Central Asia, printing in the Uyghur language appeared around 1300. After the Mongols conquered parts of Central Asia and Persia in the 1200s, paper money was printed in Tabriz in 1294, following the Chinese system. A detailed description of the Chinese printing system was written by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in the early 1300s.

Some old pieces of Medieval Arabic blockprinting from between 900 and 1300 have been found in Egypt. These were printed in black ink on paper using a rubbing method, similar to the Chinese style. Experts believe this printing method came from China.

The American art historian A. Hyatt Mayor said that "it was the Chinese who really discovered the means of communication that was to dominate until our age." Both woodblock and movable type printing were later replaced in the late 1800s by Western-style printing methods like lithography.

Movable Type Printing

Ceramic Movable Type in China

Bi Sheng (990–1051) created the first known movable-type system for printing in China around 1040 AD, during the Northern Song dynasty. He used ceramic (clay) materials. The Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (1031–1095) described how it worked:

When Bi Sheng wanted to print, he would put an iron frame on an iron plate. He would then place the clay types (characters) close together inside the frame. Once the frame was full, it became one solid block of type. He would then warm it near a fire. When the paste on the back of the types melted a little, he would press a smooth board over the surface. This made the block of type perfectly flat.

For each character, Bi Sheng had several types. For common characters, he had twenty or more types, so he could print the same character many times on one page. When the characters were not in use, he organized them with paper labels, grouped by their sounds, and kept them in wooden boxes.

Shen Kuo explained that if you only wanted to print two or three copies, this method wasn't very easy. But for printing hundreds or thousands of copies, it was incredibly fast. Bi Sheng usually worked with two forms (pages) at a time. While one page was being printed, the types for the next page were being set up. When the first page was done, the second was ready. This way, the two forms switched back and forth, and printing was done very quickly.

Clay type printing was used in China from the Song dynasty all the way to the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). However, it wasn't always popular because the ceramic types didn't hold Chinese ink very well, and they could sometimes get distorted when baked.

Metal Movable Type in China

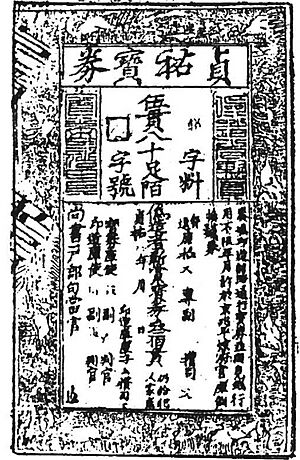

Bronze movable type printing was invented in China by the 1100s. We know this from at least 13 discoveries in China, including large bronze plates used for printing paper money and official documents. These documents, issued by the Jin (1115–1234) and Southern Song (1127–1279) dynasties, had small bronze metal types embedded in them as a way to prevent fake money. This kind of paper money printing might even go back to the 1000s.

A good example is a printed "check" from the Jin Dynasty. It has two square holes where two bronze movable types were placed. Each type was chosen from 1000 different characters, so every piece of paper money had a unique combination of markers. This made it very hard to counterfeit.

In 1298, an official named Wang Zhen wrote a book that mentioned tin movable type, which was probably used since the Southern Song dynasty. However, it didn't work well with the ink and was mostly experimental.

During the Mongol Empire (1206–1405), movable type printing spread from China to Central Asia. The Uyghurs of Central Asia used movable type, and some of their books had Chinese words printed between the pages, showing they were printed in China.

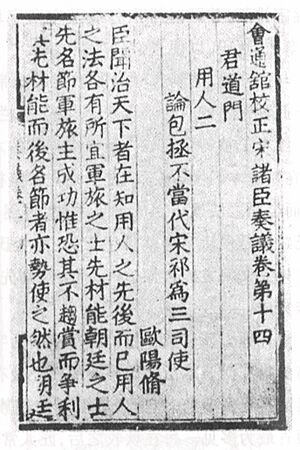

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Hua Sui used bronze type to print books in 1490. In 1574, a massive encyclopedia with 1000 volumes, called Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era, was printed using bronze movable type.

In 1725, the Qing dynasty government made 250,000 bronze movable-type characters. They used these to print 64 sets of a huge encyclopedia called Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China. Each set had 5040 volumes, meaning a total of 322,560 volumes were printed using movable type!

Wooden Movable Type in China

Wooden movable type was also first developed around 1040 AD by Bi Sheng, the same inventor who created ceramic movable type. However, it wasn't used much at first because of the wood grains and how uneven the wooden types became after soaking in ink.

In 1298, Wang Zhen, a government official during the Yuan dynasty, re-invented a way to make movable wooden types. He made over 30,000 wooden types and printed 100 copies of Records of Jingde County, a book with more than 60,000 Chinese characters. He then wrote a book explaining his invention. This system was later improved by pressing wooden blocks into sand and then casting metal types from the molds. This new method solved many problems of woodblock printing. Instead of carving a new block for every page, movable type allowed pages to be put together quickly. These smaller, reusable types could be stored and used again.

Wooden movable types continued to be used in China. As late as 1733, a 2300-volume book series was printed with 253,500 wooden movable types by order of the Yongzheng Emperor.

Some books printed in Tangut script during the Western Xia period (1038–1227) are known. One book, the Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union, found in 1991, is believed to have been printed between 1139 and 1193. Many Chinese experts think it's the earliest existing example of a book printed using wooden movable type.

One challenge with movable type in China was the huge number of logographs (characters) needed for the Chinese language. It was often faster to carve a whole woodblock for one page than to assemble a page from thousands of different types. However, if you needed to print many copies of the same document, movable type became much faster.

Wooden types were strong, but repeated printing wore down the character faces. New pieces had to be carved to replace them. Also, wooden type could soak up moisture, making the print uneven, and it was sometimes hard to remove from the paste used to hold the types together.

Metal Movable Type in Korea

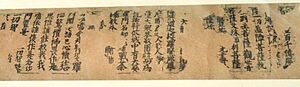

The shift from wood type to movable metal type happened in Korea during the Goryeo dynasty, around the 1200s. This was because there was a big demand for both religious and everyday books. A set of religious books, Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun, was printed with movable metal type in 1234. The credit for the first metal movable type might go to Ch'oe Yun-ŭi of the Goryeo Dynasty in 1234.

The methods for casting bronze, which were used to make coins, bells, and statues, were adapted to make metal type. Unlike the metal punch system thought to be used by Gutenberg in Europe, Koreans used a sand-casting method. A scholar from the Joseon dynasty, Song Hyon (1400s), described how Korean metal types were made:

First, letters were carved into beech wood. Then, a tray was filled with fine sandy clay from the seashore. The carved wooden letters were pressed into the sand, creating negative molds of the letters. Next, two trays were put together, and molten bronze was poured into an opening. The liquid metal flowed in, filling these molds, one by one becoming type. Finally, any rough edges were scraped and filed off, and the types were stacked up to be arranged.

Even though metal movable type printing was developed in Korea and the oldest metal print book was printed there, Korea didn't have a printing revolution like Europe did. This was because the royal family kept control of this new technique. They stopped all unofficial printing and any attempts to make printing a business. So, printing in early Korea mostly served only the small, noble groups of society.

However, Korea did see important developments in metal movable type. In 1403, King Taejong of Joseon ordered 100,000 pieces of movable type and two complete sets of fonts.

A possible solution to the challenges of movable type in Korea appeared in the early 1400s, before Gutenberg's invention in Europe. Koreans created a simpler alphabet of 24 characters called Hangul. This alphabet needed far fewer characters to create types, making printing much easier.

Movable Type in Japan

In Japan, the first Western-style movable type printing-press was brought by a Japanese mission to Europe in 1590. It was first used to print in Kazusa, Nagasaki, in 1591. However, Western printing presses were stopped after Christianity was banned in 1614. A movable type printing press taken from Korea by Toyotomi Hideyoshi's forces in 1593 was also used around the same time. In 1598, a book of Confucian teachings was printed using a Korean movable type printing press, ordered by Emperor Go-Yōzei.

Tokugawa Ieyasu set up a printing school in Kyoto and started publishing books using Japanese wooden movable type printing presses from 1599, instead of metal ones. Ieyasu oversaw the creation of 100,000 types, which were used to print many political and historical books. In 1605, books using Japanese copper movable type presses began to be published, but copper type didn't become widely used after Ieyasu died in 1616.

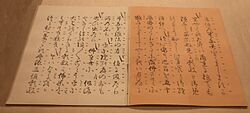

Important people who used movable type printing to create artistic books were Honami Kōetsu and Suminokura Soan. At their studio in Saga, Kyoto, they made many woodblock versions of Japanese classic stories, including both text and pictures. They essentially turned emaki (handscrolls) into printed books for more people to enjoy. These books, known as Kōetsu Books, Suminokura Books, or Saga Books, are considered the first and best printed copies of many classic tales. The Saga Book of the Tales of Ise (Ise monogatari), printed in 1608, is especially famous. Saga Books were printed on expensive paper and had many decorations, made for a small group of people who loved literature. For artistic reasons, the letters in Saga Books looked like traditional handwritten books, where several characters were written together with smooth brush strokes. This meant that sometimes a single type combined two to four characters. In one book, 2,100 characters were created, but 16% of them were used only once.

Despite the appeal of movable type, craftsmen soon decided that the flowing, handwritten style of Japanese writing looked better when reproduced using woodblocks. By 1640, woodblocks were used again for almost all printing. After the 1640s, movable type printing became less common, and books were mass-produced using traditional woodblock printing for most of the Edo period. It wasn't until the 1870s, during the Meiji period, when Japan opened up to the West and started to modernize, that movable type was used again.

Woodblock vs. Movable Type in East Asia

Even after movable type was invented in the 1000s, woodblock printing remained the main way to print in East Asia until new methods like lithography came along in the 1800s. To understand why, we need to think about the Chinese language and the costs of printing.

Because the Chinese language doesn't use an alphabet, a set of movable type usually needed 100,000 or more blocks. This was a very big investment. Common characters needed 20 or more copies, while rarer characters only needed one. When using wood, the characters were either carved into a large block and then cut into individual pieces, or the blocks were cut first and then the characters carved. Either way, the size and height of the types had to be very carefully controlled to make the printed pages look good.

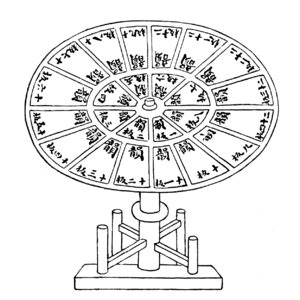

To arrange the types, Wang Zhen used spinning tables about 2 meters wide. The characters were organized on these tables by their sounds. Each character had a number, and one person would call out the number while another person found the type.

This system worked well for printing many copies. Wang Zhen's first project, printing 100 copies of a 60,000-character local guide, was done in less than a month. But for smaller print jobs, which were common at the time, it wasn't much better than woodblocks. To reprint a book, the types had to be set up and checked again. With woodblocks, you could just store the blocks and reuse them. Individual wooden characters also didn't last as long as full woodblocks. When metal type was introduced, it was harder to make beautiful characters by carving them directly.

We don't know if metal movable types used in China from the late 1400s were cast from molds or carved one by one. Even if they were cast, there weren't the same cost savings as with alphabetic systems that use a small number of different characters. Carving on bronze cost much more than carving on wood, and a set of metal type might have 200,000 to 400,000 characters. Also, the traditional Chinese ink, made from pine soot and glue, didn't work well with the tin that was first used for metal types.

Because of all these reasons, movable type was first used by government offices that needed to print many copies, and by traveling printers who made family records. These printers might carry 20,000 wooden types with them and carve any other needed characters on the spot. But small local printers often found that wooden blocks were better for their needs.

Mechanical Presses

Mechanical presses were later invented by Europeans. In East Asia, printing remained a manual, hard process where people pressed the back of the paper onto the inked block by hand, using a rubbing tool. In Korea, the first printing presses were introduced quite late, between 1881 and 1883. In Japan, after a short time in the 1590s, Gutenberg's printing press arrived in Nagasaki in 1848 on a Dutch ship.

See also

- East Asian typography

- History of Western typography

- Hua Sui

- Printing press

- Publishing industry in China

- Samuel Dyer

- Typography

- Wang Zhen, also known as Wang Chen