Science and technology of the Song dynasty facts for kids

The Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) in China was a time of amazing breakthroughs in science and technology. Many smart people, including government officials and skilled craftspeople, helped create new inventions. For example, Shen Kuo (1031–1095) was a brilliant inventor who improved Chinese astronomy and mathematics. He even figured out the idea of true north using a magnetic compass for the first time.

Ordinary craftspeople also made big changes. Bi Sheng (972–1051) invented movable type printing. This was a huge step forward, even before the printing press in Europe.

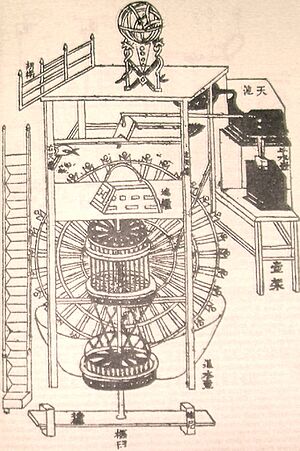

Chinese engineers had a long history of creating advanced machines. Su Song, a Song engineer, built a giant water-powered clock tower. He knew he was building on the ideas of older inventors like Zhang Heng (78–139), who made an armillary sphere that moved automatically with water power.

Movable type printing made it easier to print books. This helped more people learn to read and enjoy stories. New gunpowder weapons, like cannons, helped the Song army defend itself. They fought against powerful enemies like the Liao and Jin dynasties. However, the Song dynasty eventually fell to the Mongol forces led by Kublai Khan in the late 1200s.

The Song dynasty also saw big improvements in building, sailing, and working with metals. The windmill even came to China during the 1200s. These inventions, along with the invention of paper money, helped the economy grow and thrive. People like Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) and Shen Kuo also started studying old objects and writings. This was an early form of archaeology. Advances were also made in forensics by Song Ci (1186–1249). He wrote about how to investigate deaths and even how to give first aid.

Contents

Smart Inventors and Amazing Machines

Brilliant Thinkers

People like Shen Kuo (1031–1095) and Su Song (1020–1101) were known as Polymaths. This means they knew a lot about many different subjects. They were key to the scientific and technological progress of the Song era.

Shen Kuo is famous for discovering true north. He also figured out that the magnetic compass needle points slightly away from true north. This is called magnetic declination. This discovery helped sailors navigate the seas much more accurately. Shen also wrote about Bi Sheng, the inventor of movable type printing.

Shen was also very interested in geology. He thought that land changed over time due to erosion and climate change. He saw fossils of sea creatures in mountains far from the ocean. This made him believe that these areas were once ancient seashores. He also found petrified bamboo in dry northern areas where bamboo didn't grow. This led him to think that climates change over long periods.

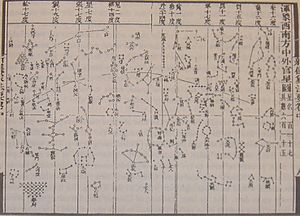

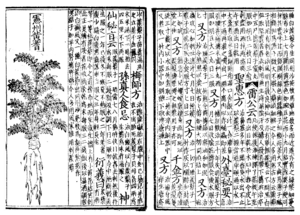

Su Song, another brilliant scholar, wrote a famous book about medicine in 1070. It covered plants, animals, metals, and minerals. He also created a large map of the stars. His detailed maps helped solve a border dispute with the Liao dynasty.

Su Song's most famous invention was his water-powered astronomical clock tower. It had a moving armillary sphere on top. This tower was built in the capital city of Kaifeng in 1088. Su's clock tower used a special "escapement" mechanism. This was two centuries before it was used in European clocks. His clock also had the world's earliest known chain drive for power. The Song government loved to hire smart officials like Shen Kuo and Su Song. Their knowledge helped the government, the military, the economy, and the people.

Shen Kuo was interested in many subjects. These included mathematics, geography, geology, economics, engineering, medicine, and military strategy. Once, on a trip, he made a 3D map of mountains and rivers using wood and sawdust. He also improved the design of the water clock and the armillary sphere. Shen Kuo even experimented with the camera obscura, a device that projects an image.

Odometer and South-Pointing Chariot

Many other important inventors lived during the Song dynasty. One invention was the odometer, a device that measured distance. It had been known in China since the ancient Han dynasty. The Song Shi (a historical book from 1345) gives a detailed description of it.

The Song Shi says the odometer carriage was red and decorated with flowers and birds. It had two levels. For every li (about 0.5 km) traveled, a wooden figure on the lower level would strike a drum. For every ten li, a figure on the upper level would strike a bell. The carriage was pulled by four horses.

The book explains how the gears worked: "When the middle horizontal wheel has made 1 revolution, the carriage will have gone 1 li and the wooden figure in the lower story will strike the drum. When the upper horizontal wheel has made 1 revolution, the carriage will have gone 10 li and the figure in the upper storey will strike the bell." It used 8 wheels with 285 teeth in total.

During the Song period, the odometer was sometimes combined with the south-pointing chariot. This device, likely invented by Ma Jun (200–265), always pointed south. It used complex gears to stay pointed in one direction, no matter how the chariot turned. It used mechanical "dead reckoning" to navigate, not a compass.

In 1027, Yan Su, another polymath, recreated a south-pointing chariot. In 1107, an engineer named Wu Deren combined the south-pointing chariot and the odometer into one vehicle. These combined vehicles were used in a big ceremony that year.

Revolving Bookcases

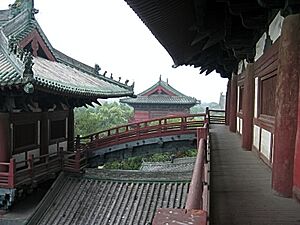

Besides clocks and chariots, the Song dynasty had other amazing mechanical inventions. Revolving bookcases were very popular in Buddhist temples during the Song dynasty. The oldest one still around today is from the 12th century at the Longxing Monastery.

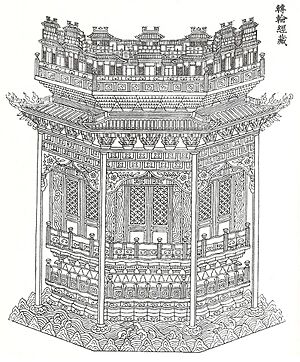

There were nine famous revolving bookcases during the Song period. One was even shown in a book called Yingzao Fashi (1103), which was about building methods. A Muslim traveler named Shah Rukh visited China in 1420. He described a huge, octagonal revolving bookcase in Ganzhou. He called it a "kiosque." It had fifteen stories and was made of polished, gilded wood. He said, "A person in the vault can with a trifling exertion cause this great kiosque to revolve." He was very impressed by the craftsmanship.

Textile Machines

In manufacturing textiles (cloth), the Chinese invented the "quilling-wheel" by the 1100s. The mechanical belt drive was also known since the 1000s. Qin Guan's book Can Shu (1090) described a silk-reeling machine. It used a foot pedal to power the main reel. This machine was shown in a book from 1237.

Movable Type Printing

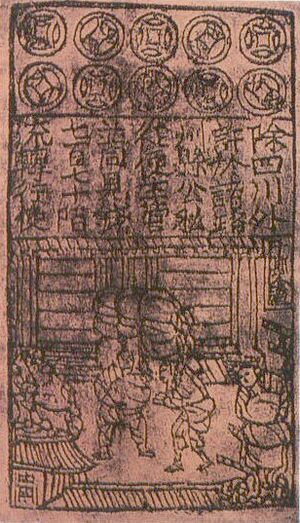

Printing with movable type was invented by Bi Sheng (990–1051) in the 11th century. Shen Kuo wrote about Bi Sheng's work in his book Dream Pool Essays. Movable type, along with woodblock printing, helped more people learn to read. This was because books and other printed materials could be made much faster. Parents could now encourage their sons to study for the imperial examinations. This helped more people join the government.

Later, movable type was improved in Korea. They used metal characters instead of Bi Sheng's baked clay ones. In China, Wang Zhen invented wooden movable type around 1298. Hua Sui invented bronze movable type in 1490. Even though movable type and woodblock printing were used for centuries, the European printing press was eventually adopted in East Asia.

China already had a good system for making paper. The process was perfected by Cai Lun (50–121) in 105 CE. It was widely used for writing by the 200s. The Song dynasty was the first government in the world to print paper money, called banknotes. Toilet paper had been used in China since the 500s. Paper bags for tea leaves were used by the 600s. By the Song dynasty, government officials were even rewarded with paper money in paper envelopes.

The Song dynasty had many industries, both private and government-run. They needed to meet the needs of a growing population of over 100 million people. For example, the Song government had several factories just for printing paper money. In 1175, the factory in Hangzhou alone employed over a thousand workers every day.

Gunpowder and Warfare

New military technology helped the Song dynasty defend itself.

Flamethrowers

The flamethrower was first used in ancient Greece. It used "Greek fire," a very flammable liquid, in a hose-like device. The first mention of Greek Fire in China was in 917. In 919, a pump was used to spray "fierce fire oil" that water couldn't put out. This was the first clear Chinese mention of a flamethrower using a chemical liquid.

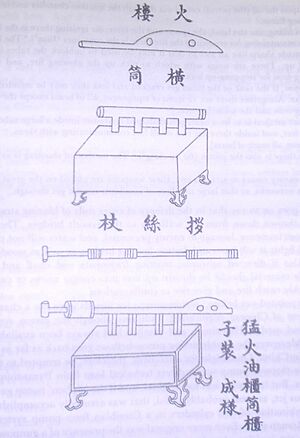

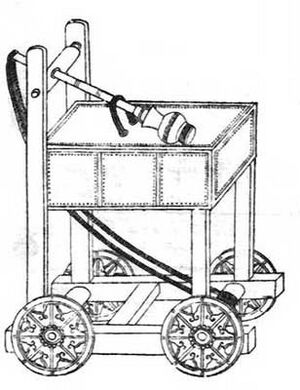

In 919, Chinese naval forces used "fire oil" to burn an enemy fleet. This was one of the first times gunpowder was used in battle. The Chinese used double-piston bellows to pump the liquid. It was lit by a slow-burning gunpowder match, creating a continuous stream of flame. This device was shown in a military book from 1044 called the Wujing Zongyao. In 975, Song naval forces fought against the Southern Tang state. The Southern Tang tried to use flamethrowers, but strong winds blew the fire back onto them.

Fire Lances

The earliest known recipes for gunpowder come from the Wujing Zongyao text of 1044. It described explosive bombs thrown by catapults. The first gun barrels and cannons appeared in late Song China. The earliest picture of a Chinese "fire lance" (a mix of a flamethrower and a gun) is from a Buddhist painting around 950.

These "fire-lances" were common by the early 1100s. They used hollow bamboo poles to shoot sand, lead pellets, sharp metal pieces, and even gunpowder-powered arrows. Later, strong iron tubes replaced the bamboo. The name changed from "fire-spear" to "fire-tube." This was an early version of the gun. The ancestor of the cannon was called the "multiple bullets magazine erupter." It was a bronze or iron tube filled with about 100 lead balls. In 1132, Song Chinese forces used fire lances against the Jin dynasty.

Guns

An early picture of a gun is a sculpture from 1128 in Sichuan. It shows a figure holding a vase-shaped gun, firing flames and a cannonball. The oldest actual metal handgun found is the Heilongjiang hand cannon from 1288. The Chinese also discovered how to make explosive cannonball shells by filling them with gunpowder. A book from the 1300s, the Huolongjing, described a Song-era iron cannon. It was called the "flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor."

The book said: "The shells are made of cast iron, as large as a bowl and shaped like a ball. Inside they contain half a pound of 'magic' gunpowder. They are sent flying towards the enemy camp from an eruptor; and when they get there a sound like a thunder-clap is heard, and flashes of light appear. If ten of these shells are fired successfully into the enemy camp, the whole place will be set ablaze..."

Early Song cannons were first called by the same name as the Chinese trebuchet catapult. A later scholar explained that these "fire trebuchets" were used to throw fire-weapons like fire-balls and fire-lances. He said they were the ancestors of the cannon.

Land Mines

The Huolongjing (1300s) also described the use of explosive land mines. The Song Chinese used them against the Mongols in 1277. The invention of the land mine is credited to Luo Qianxia. Later Chinese books showed that land mines used a tripwire or a trap that released weights. These weights would spin a steel wheel, creating sparks to light the fuses of the mines.

Rockets

The Song also used the earliest known gunpowder-powered rockets in warfare during the late 1200s. The first form was the "fire arrow." When the Song capital of Kaifeng fell in 1126, it's said that 20,000 fire arrows were given to the Jurchens. An earlier Chinese book from 1044 described using large crossbows to fire arrows with gunpowder packets near their heads.

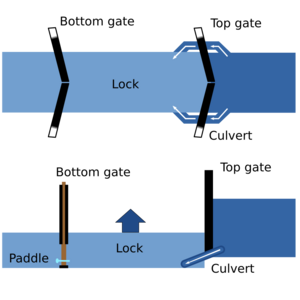

Building and Engineering

In ancient China, sluice gates and canal locks were known since at least the 1st century BCE. During the Song dynasty, the pound lock was invented in 984 by engineer Qiao Weiyue. This helped solve a problem on the Grand Canal. Ships were often damaged and robbed when passing over difficult sections.

The Song Shi historical text says that in 984, Qiao Weiyue built two gates on the West River. The space between the gates was about 250 feet. When the gates were closed, water would build up to the right level. Then, it would be let out. This system stopped corruption and made boat travel much smoother.

This new system became very popular. Shen Kuo wrote about it in his Dream Pool Essays (1088). He said that pound lock gates saved a lot of labor and money each year. Before, boats could only carry about 21 tons of rice. After the locks, they could carry 28 tons. By Shen Kuo's time, government boats could carry up to 49.5 tons, and private boats even more. Shen Kuo also noted that sluice gates were good for adding silt to fields to make them fertile.

The drydock was known in ancient Egypt, but Shen Kuo wrote about its use in China in the 11th century. In his Dream Pool Essays (1088), he described how large dragon ships were repaired. A big basin was dug, and beams were laid down. Water was let in, the ships were floated over the beams, and then the water was pumped out. This left the ships "quite in the air" for repairs. After repairs, water was let back in, and the ships floated out. The basin was then covered to protect the ships.

Sailing and Ships

Background

The Chinese of the Song dynasty were skilled sailors. They traveled to places as far away as Egypt. Their large ships had rudders at the back for steering and were guided by the compass. Even before Shen Kuo described the magnetic compass for sailors, a military book from 1044 described a simple compass. It was a heated iron needle placed in water, which became weakly magnetic. This was used for land navigation.

Ships and Travel

Chinese books from this time describe seaports, merchant ships, and overseas trade. In 1117, Zhu Yu wrote about the magnetic compass for navigation. He also described a long line with a hook used to collect mud from the seafloor. Sailors could tell where they were by the smell and look of the mud.

Zhu Yu also wrote about watertight compartments in ship hulls. These prevented the ship from sinking if it was damaged. He also described the fore-and-aft lug sail and how ships could sail against the wind. In 1973, a 78-foot-long Song trade ship from around 1277 was found. It had 12 watertight compartments in its hull, confirming Zhu Yu's writings.

Maritime culture grew during the Song period. There was a lot of activity on rivers and canals. Government ships carried grain, private ships traded goods, and many fishers worked in small boats. Rich people also enjoyed their fancy private yachts.

In 1178, Zhou Qufei, a customs officer, wrote about Chinese seagoing ships. He said they were "like houses" and their sails were "like great clouds in the sky." He noted that a single ship could carry hundreds of men and a year's supply of food. He also mentioned the dangers of sea travel, like storms and hidden rocks.

The Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta (1304–1377) wrote even more about Chinese ships. He said that only Chinese junks were used in the seas around China. The largest ones had twelve masts, and smaller ones had three. He said each large ship had 1,000 men, including 600 sailors and 400 soldiers.

Ibn Battuta described how they were built. He noted the separate watertight compartments in the hulls. He said: "two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised, and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails." He also mentioned that the ships had four decks with cabins for merchants. These cabins had locks and keys. Merchants would bring their families, and sailors would even grow vegetables in wooden tubs on board.

Paddle-Wheel Ships

The Song dynasty also focused on building efficient paddle wheel ships. These had been known in China since at least the 700s. In 1134, Wu Ge built paddle wheel warships with nine or thirteen wheels. Some Song paddle wheel ships were so big they had 12 wheels on each side.

In 1135, the general Yue Fei used a clever trick. He filled a lake with weeds and logs to trap enemy paddle wheel ships. This allowed his forces to board them and win. In 1161, gunpowder bombs and paddle wheel ships were used effectively by the Song Chinese in battles against the Jin dynasty. These battles helped stop the Jurchen invasion of Southern Song China.

In 1183, the Nanjing naval commander Chen Tang was rewarded for building many paddle wheel ships. The Song emperor valued these fast ships. Paddle wheel ships were also used as tugboats for towing other vessels.

Working with Metals

The art of working with metals improved greatly during the Song dynasty. The Chinese had known how to make steel since the 1st century BCE. During the 11th century, the Song developed two new ways to make steel. One was a simpler method, and the other was an early version of the modern Bessemer process. This process made steel better by removing carbon.

The amount of iron produced increased six times between 806 and 1078. By 1078, Song China was making about 127,000 tons of iron each year. To make iron, huge bellows powered by hydraulics (large waterwheels) were used. This process used a lot of charcoal, which led to many forests being cut down in northern China. However, by the late 11th century, the Chinese found that they could use bituminous coke (a type of coal) instead of charcoal. This saved many forests.

The huge increase in iron and steel production was due to the Song dynasty's needs for its military, private businesses, and new canals. Iron was used for weapons, tools, coins, buildings, bells, statues, and parts for machines like the hydraulic-powered trip hammer.

A historian named Robert Hartwell said that China's iron and coal production in the 12th century was as much as or even more than England's production during the early Industrial Revolution (late 1700s). However, the Chinese didn't use coal to power machines in the same way. Some areas were known for their iron industry. For example, the official Su Shi wrote in 1078 that one area had 36 iron smelters, each employing hundreds of people.

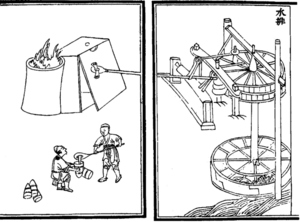

Wind Power

The Chinese understood the power of wind long before the windmill came to China. They used bellows to blow air into kilns and furnaces. These were likely used since the Shang dynasty (1600–1050 BCE) for bronze casting. They were definitely used for blast furnaces from the 6th century BCE.

In 31 CE, the engineer Du Shi used horizontal waterwheels and gears to power large bellows for smelting cast iron. Bellows continued to be used for metalwork. Other uses for wind power were also found. The Han dynasty artisan Ding Huan (around 180 CE) invented a rotary fan. This could be used as a simple air conditioner. It had seven large wheels powered by hand. By the Tang dynasty (618–907), palaces had water-powered rotary fans for air conditioning.

A Chinese rotary fan winnowing machine was shown in a book from 1313. The windmill finally came to China in the early 13th century from the Islamic world. This happened during the late Song dynasty.

A Persian scholar wrote around 850 CE about windmills. Later, the Chinese used the "fore-and-aft" sails from their junk ships on horizontal windmills. These windmills powered chain pumps used for irrigation. These types of windmills were still used in modern times.

After the windmill, wind power was used in other devices and even vehicles. The "sailing carriage" appeared by the 1500s. European travelers were surprised to see large wheelbarrows with masts and sails. These sails helped push them along with the wind.

Archaeology

During the early Song dynasty (960–1279), the study of archaeology began. Educated people were interested in old objects. They wanted to use ancient vessels in state ceremonies. Shen Kuo studied ancient bronzeware and inscriptions. He also wrote about metallurgy, optics, and astronomy.

Some Song scholars, like Zhao Mingcheng (1081–1129), believed that archaeological evidence was more reliable than written history. They found that old records were sometimes wrong when compared to actual discoveries. Hong Mai (1123–1202) used ancient Han dynasty vessels to show that some descriptions in an archaeological book were incorrect.

Geology and Climate

Shen Kuo also had ideas about geology and climatology in his Dream Pool Essays (1088). Shen thought that land changed over time due to constant erosion, uplift, and silt being deposited. He saw horizontal layers of fossils in a cliff in the Taihang Mountains. This made him think that the area was once an ancient seashore that had moved hundreds of miles over a very long time. Shen also wrote that since petrified bamboo was found underground in a dry northern area where it didn't grow, climates must have shifted over time.

Forensics

Early ideas in forensic science started in China during the Song dynasty. When a murder was suspected, officials would visit the scene. They would try to figure out if the death was natural, accidental, or caused by foul play. If it was a crime, a local official would investigate. They would draw sketches of injuries on the body and have witnesses sign them for court.

Details of these investigations are in books like Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified by judge and doctor Song Ci (1186–1249). His book describes different types of death and how physical exams (autopsies) can tell them apart. Song also gave information on first aid for people close to death, including how to help someone who had drowned.

|

See also

- History of science and technology in China

- List of Chinese discoveries

- List of Chinese inventions

- Science and technology of the Han dynasty

- Science and technology of the Tang dynasty

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |