History of gunpowder facts for kids

Gunpowder was the first explosive ever made. It's famous as one of China's "Four Great Inventions." It was invented in China during the late Tang dynasty (around the 800s). The first recorded recipe for gunpowder appeared in the Song dynasty (around the 1000s).

Knowledge of gunpowder quickly spread across Asia and Europe. This might have happened because of the Mongol conquests in the 1200s. Written recipes for gunpowder appeared in the Middle East between 1240 and 1280. In Europe, a recipe was written by Roger Bacon in 1267.

Gunpowder was used in wars from at least the 900s. It powered weapons like fire arrows, bombs, and the fire lance. Later, in the 1200s, guns appeared. While guns replaced fire lances, other gunpowder weapons like rockets and fire arrows continued to be used. Bombs also kept developing into modern weapons like grenades and mines.

Gunpowder was also used for fun things like fireworks. It helped with building projects like mining and digging tunnels.

As guns improved, large artillery pieces, called bombards, became common in the 1400s. Countries like the Duchy of Burgundy led the way. By the 1600s, firearms were very important in early modern warfare in Europe.

Better cannons that fired heavier shots led to new types of forts. These were called star forts or bastions. Old city walls and castles were no longer strong enough for defense. Gunpowder technology also spread to the Islamic world, India, Korea, and Japan. The "Gunpowder Empires" of the early modern period were the Mughal Empire, Safavid Empire, and Ottoman Empire.

In the 1800s, gunpowder was used less in warfare. This was because "smokeless powder" was invented. Today, gunpowder is often called "black powder" to tell it apart from modern gun propellants.

Contents

How Gunpowder Started in China

Gunpowder was first made in China. It was a big discovery that changed warfare and many other things.

Early Discoveries

Gunpowder was invented in China sometime in the first 1000 years AD. The earliest possible mention of it was in 142 AD. A Chinese alchemist named Wei Boyang wrote about a mix of three powders. He said they would "fly and dance" very strongly. He was looking for ways to live forever, not to make weapons.

Taoist alchemists kept working with sulfur and saltpeter. These are key ingredients in gunpowder. They were trying to find an "elixir of life" or change materials into gold. In 300 AD, another Taoist, Ge Hong, wrote about heating saltpeter, pine resin, and charcoal. This made a purple powder and strong fumes.

In 492 AD, alchemists noticed that saltpeter burned with a purple flame. This helped them clean the substance better. During the Tang dynasty, alchemists used saltpeter to process other chemicals.

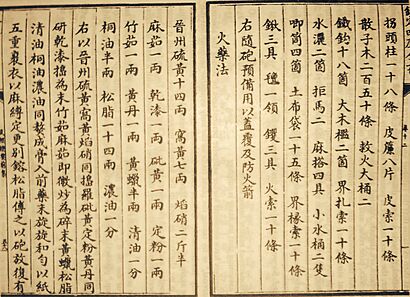

The first clear mention of gunpowder in China was in the Tang dynasty. One recipe from 808 AD combined sulfur, saltpeter, and a herb. About 50 years later, a Taoist text warned about dangerous mixes. One mix of sulfur, realgar (a chemical), saltpeter, and honey caused burns and fires. Alchemists called this discovery "fire medicine" (huoyao). This name is still used for gunpowder in China today.

The oldest surviving recipe for gunpowder is from 1044 AD. It's in a military book called Wujing Zongyao. This book showed many old or unusual Chinese weapons. This means gunpowder was used in weapons long before modern guns. These early gunpowder weapons had strange names. Some were "flying incendiary club for subjugating demons" or "ten-thousand fire flying sand magic bomb." Over time, these weapons became simpler. The main types were gunpowder arrows, bombs, and guns.

First Weapons: Fire Arrows

Early gunpowder didn't have enough saltpeter to explode. But it was very flammable. So, early weapons used it to cause fires and shock. One of the first such weapons was the fire arrow. The first possible use of fire arrows was in 904 AD. An officer named Zheng Fan used them to burn a city gate. He and his troops then rushed into the city.

Arrows with gunpowder were very useful. The air rushing around the arrow as it flew helped the gunpowder burn strongly.

Rocket Power!

At first, fire arrows were just arrows with gunpowder bags tied to them. But later, they became projectiles that were pushed by gunpowder themselves. These were early rockets. We don't know exactly when this happened.

In 969 AD, two Song generals invented a fire arrow that used gunpowder tubes to push it. They showed it to the emperor in 970 AD. However, some historians think rockets didn't exist before the 1100s. This is because the gunpowder recipes from the Wujing Zongyao weren't strong enough for rockets. Other historians say there's little proof of rockets before 1200. They think rockets were used in war only after the mid-1200s. Rockets were used by the Song navy in a military practice in 1245.

In 975 AD, the Song dynasty used fire arrows to destroy an enemy fleet. In 994 AD, the Liao dynasty attacked the Song with 100,000 soldiers. The Song used fire arrows to push them back. In 1000 AD, a soldier showed his own gunpowder arrows and early bombs. He was greatly rewarded.

The emperor's court was very interested in gunpowder. They encouraged new inventions and shared military technology. For example, in 1002 AD, a local soldier showed his fireballs and gunpowder arrows. The emperor ordered that the plans be printed and shared.

The Song court rewarded military inventors. This led to many new inventions. Gunpowder and fire arrow production grew a lot in the 1000s. The court built large gunpowder factories in the capital city of Kaifeng. In 1083, the emperor sent 100,000 gunpowder arrows to one army base and 250,000 to another.

There is less proof of gunpowder in the Liao dynasty and Western Xia. But in 1073, the Song emperor banned trading sulfur and saltpeter across the Liao border. This suggests the Liao knew about gunpowder and wanted its ingredients.

-

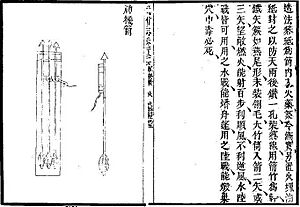

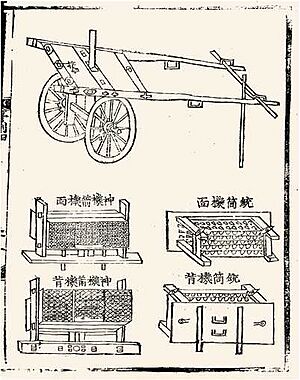

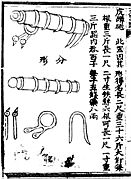

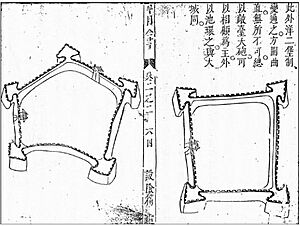

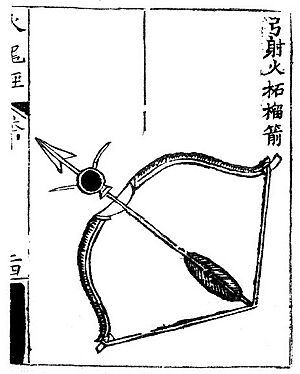

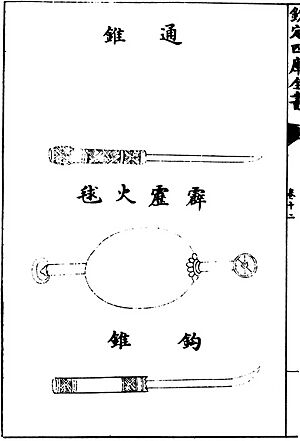

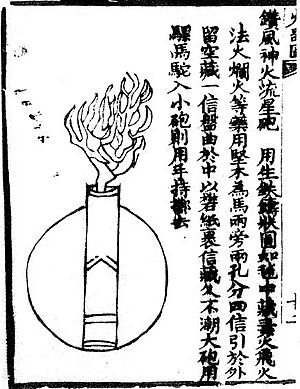

A picture of fire arrow launchers from the Wubei Zhi (1621). This launcher is made from baskets.

-

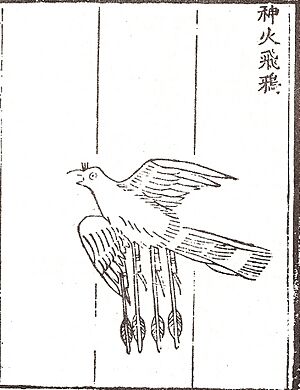

The 'divine fire arrow screen' from the Huolongjing. This launcher holds 100 fire arrows.

Explosive Bombs

Gunpowder bombs were mentioned as early as the 1000s. In 1000 AD, a soldier showed his "gunpowder pots" (early bombs that shot fire). In the military book Wujing Zongyao (1044), bombs like the "thunderclap bomb" were described. But detailed stories of their use appeared later, in the 1100s.

The Jurchen people formed the Jin dynasty in 1115. They allied with the Song and quickly became powerful. They defeated the Liao dynasty. The Song-Jin alliance then broke, and the Jin attacked the Song.

For the first time, two major powers had strong gunpowder weapons. The Jin attacked the Song capital of Kaifeng in 1126. The Song defenders used gunpowder arrows, fire bombs, and a new weapon called the "thunderclap bomb." One person wrote that these bombs "threw them into great confusion. Many fled, screaming in fright."

The Jin army left Kaifeng but returned later with their own gunpowder bombs. These were made by Song artisans they had captured. Records show the Jin used gunpowder arrows and trebuchets to throw bombs. The Song used gunpowder arrows, fire bombs, thunderclap bombs, and a new "molten metal bomb." The Jin captured Kaifeng despite these defenses.

The molten metal bomb was used again in 1129. A Song general used them against Jin forces. He said, "Wherever the gunpowder touched, everything would disintegrate without a trace."

The Fire Lance: A Proto-Gun

The Song capital moved to Hangzhou. The Jin followed, and fighting continued. This led to the first "proto-gun," the fire lance. It was first used by Song forces against the Jin in 1132. Most Chinese scholars think the fire lance appeared during these wars. But an old silk painting from the 900s might show an earlier fire lance.

The siege of De'an in 1132 was important. The gunpowder in the fire lances was called "fire bomb medicine." This might mean a new, stronger gunpowder recipe was used. It could also mean they recognized gunpowder's special use in war.

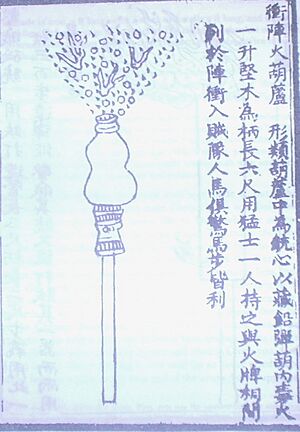

Fire lances were used against soldiers into the Ming dynasty. In 1163, Song commander Wei Sheng built war carts with fire lances sticking out. These carts protected trebuchets that threw fire bombs. By the 1200s, fire lances were even used by cavalry.

Gunpowder technology also spread to naval warfare. In 1129, the Song emperor ordered all warships to have trebuchets for throwing gunpowder bombs. Older weapons like fire arrows were also used.

In 1159, a Song fleet used gunpowder arrows to set fire to hundreds of Jin ships. In 1161, Song boats ambushed a Jin transport fleet. They launched thunderclap bombs, causing many Jin soldiers to drown in the Yangtze River.

One description of the thunderclap bomb used in naval battles says: "It was made with paper (carton) and filled with lime and sulphur. These thunderclap bombs came dropping down from the air, and upon meeting the water exploded with a noise like thunder, the sulphur bursting into flames." The smoke and lime blinded the enemy.

Thunderclap bombs were used again in 1206–1207 during the Jin siege of Xiangyang. Both sides had gunpowder weapons. The Song used fire arrows, fire bombs, and thunderclap bombs. The thunderclap bombs made Jin soldiers and horses panic. The Song even launched a night attack using boats with gunpowder arrows and thunderclap bombs. This caused a huge panic among the Jin troops.

Stronger Bombs: Iron Shells

The invention of the iron bomb was very important. A story says a fox hunter named Iron Li invented it around 1189. He used a ceramic explosive to scare foxes into his nets. While this story is fun, it's not clear why it led to iron bombs.

The first iron bomb appeared in 1221 at the siege of Qizhou. This time, the Jin army had the better technology. The Song commander, Zhao Yurong, described the Jin's iron bombs. He said they were "like gourds, but with a small mouth. They are made with pig iron, about two inches thick, and they cause the city's walls to shake."

These bombs blew apart houses and battered towers. Defenders were blasted from their positions. The Jin captured Qizhou. Zhao Yurong later found that the "bones and skeletons were so mixed up that there was no way to tell who was who."

The First Guns: Hand Cannons

The early fire lance is seen as the ancestor of firearms. But it wasn't a true gun because it didn't shoot a projectile. A true gun uses gunpowder to push a bullet or cannonball out of a tube.

In 1259, a "fire-emitting lance" appeared. It was made from a large bamboo tube with a "pellet wad" inside. When fired, it shot the pellet wad out. This pellet wad might be the first true bullet. Fire lances then changed from bamboo or paper tubes to metal ones. This helped them handle the strong pressure of gunpowder.

From fire lances came other gunpowder weapons. Some shot poisonous gas and porcelain shards. Others shot sand and chemicals. Some, like the "phalanx-charging fire gourd," shot lead pellets.

The oldest picture that might show a hand cannon is a rock carving from 1128. This is much earlier than any found cannons. So, the idea of a cannon might have existed since the 1100s. However, some experts disagree.

Actual hand cannons (huochong) have been found from the 1200s. The oldest clearly dated gun is the Xanadu Gun from 1298. It was found at the Mongol summer palace in Inner Mongolia. It's small, weighing just over six kilograms.

Another old gun, the Heilongjiang hand cannon, is thought to be from 1288. In 1287, soldiers used hand cannons against a rebel camp. The cannons "caused great damage" and made the enemy fight each other. In 1288, these "gun-soldiers" could carry the hand cannons on their backs. This battle was also the first time the word chong was used for metal firearms.

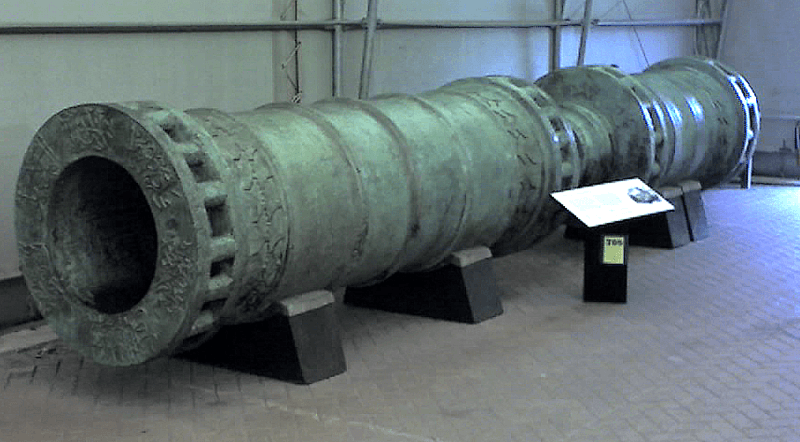

The Wuwei Bronze Cannon, found in 1980, might be the oldest and largest cannon from the 1200s. It's 100 centimeters long and weighs 108 kilograms. It had an iron ball inside. Some historians think guns appeared by 1220. Others say around 1280 for a "true" cannon.

It seems likely that the gun was invented sometime in the 1200s.

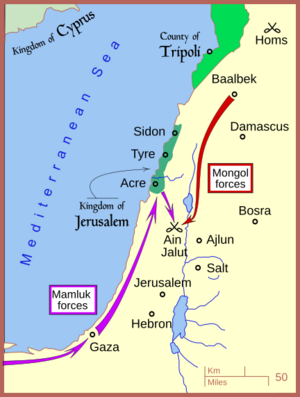

How Mongols Used Gunpowder

The Mongols played a big part in spreading gunpowder technology. They were good at using foreign experts, including Chinese artisans. These artisans traveled with Mongol armies far into the west and east. However, there are not many written records from the Mongols themselves. Some historians doubt the Mongols' role in spreading gunpowder. But others believe the Mongol Empire used gunpowder weapons and were "the first gunpowder empire."

Fighting the Jin Dynasty

The Mongols first invaded the Jin dynasty in 1211. They fully conquered it by 1234. In 1232, the Mongols attacked the Jin capital of Kaifeng. They used gunpowder weapons along with other siege methods. A Jin scholar wrote that "bombs rained down as [the enemy] advanced."

The Jin defenders also used gunpowder bombs and fire arrows. One bomb was called the "heaven-shaking-thunder bomb." A witness wrote that when Mongol troops met one, "several men at a time would be turned into ashes."

The History of Jin describes this bomb: "The heaven-shaking-thunder bomb is an iron vessel filled with gunpowder. When lighted with fire and shot off, it goes off like a crash of thunder that can be heard for a hundred li [about 50 km], burning an expanse of land more than half a mu [a small area], and the fire can even penetrate iron armor." These bombs exploded and sent iron pieces flying, killing people and horses from far away.

The Jin also used an improved fire lance called the flying fire lance. It had a tube made of 16 layers of paper. It was filled with charcoal, iron pieces, sulfur, and saltpeter. When fired, flames shot out more than three meters. Mongol soldiers were very afraid of the flying fire lance and the heaven-shaking-thunder bomb.

Kaifeng held out for a year before the Jin emperor fled. Even after the Jin emperor died in 1234, one loyal general used metal to make explosives against the Mongols. But the Mongol Empire could not be stopped. By 1234, both the Western Xia and Jin dynasties were conquered.

Fighting the Song Dynasty

The Mongol army then moved south. In 1237, they attacked the Song city of Anfeng. They used "gunpowder bombs [huo pao] to burn the [defensive] towers." These bombs were very large. "Several hundred men hurled one bomb, and if it hit the tower it would immediately smash it to pieces." The Song defenders rebuilt their towers and fought back with their own bombs.

By the mid-1200s, gunpowder weapons were very important for the Song army. In 1257, a Song official said a city arsenal should have hundreds of thousands of iron bombshells. He also said it should make thousands more each month. He was disappointed to find very few bombs in one arsenal.

Luckily for the Song, the Mongol leader died in 1259. The war paused until 1269, when Kublai Khan led the Mongols. The Mongols then attacked the twin fortress cities of Xiangyang and Fancheng. This was one of the longest sieges ever, lasting from 1268 to 1273.

In 1273, the Mongols got help from two Muslim engineers. They built new trebuchets that could throw larger missiles further. One account says, "when the machinery went off the noise shook heaven and earth; every thing that [the missile] hit was broken and destroyed." Xiangyang fell in 1273.

Gunpowder bombs were used again in 1275 at the Siege of Changzhou. The Mongol army bombarded the city with fire bombs before attacking. This led to a huge number of deaths. The war ended four years later. In 1277, 250 defenders set off a huge iron bomb when they knew they would lose. The History of Song says, "the noise was like a tremendous thunderclap, shaking the walls and ground, and the smoke filled up the heavens outside. Many of the troops [outside] were startled to death."

In 1280, a large gunpowder storage in Yangzhou accidentally exploded. It was so powerful that 100 guards were killed instantly. Wooden beams were blown over 3 kilometers away, and a crater more than 3 meters deep was formed.

By the mid-1300s, the explosive power of gunpowder was perfected in China. The amount of saltpeter in gunpowder recipes increased a lot. The Chinese also learned to make explosive round shot by filling hollow shells with this stronger gunpowder.

Spreading to Europe and Japan

Gunpowder might have been used during the Mongol invasions of Europe. Some sources mention "fire catapults" and "naphtha-shooters." But there's no strong proof that Mongols regularly used gunpowder weapons outside of China.

Soon after the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274–1281), the Japanese drew a picture of a bomb. They called it tetsuhau, which might have been the Chinese thunder crash bomb. Underwater findings confirmed that the Mongols had bombs in their invasion fleet. X-rays of bomb shells show they contained gunpowder and scrap iron. Japanese writings also mention iron and bamboo pao that made "light and fire" and shot iron bullets.

One Japanese account of the Mongol invasion says: "But whenever the (Mongol) soldiers took to flight, they sent iron bomb-shells (tetsuho) flying against us, which made our side dizzy and confused. Our soldiers were frightened out of their wits by the thundering explosions; their eyes were blinded, their ears deafened, so that they could hardly distinguish east from west."

How Gunpowder Spread Around the World

Most experts agree that the gun was invented in China. However, some theories suggest it was invented in Europe, the Islamic world, or India. These theories often lack strong evidence or clear dates. For example, some say gunpowder was invented by Berthold Schwarz in Europe. But he might be a legendary figure. Others point to cannons used by Mamluks in 1260. But the text describing this is from much later.

People who support the Chinese invention theory point out that outside China, gunpowder appeared ready for military use. It didn't go through centuries of experiments like in China. Early European gunpowder recipes even had the same useless ingredients as Chinese ones, like poisons. This suggests the knowledge was transferred.

Also, early Muslim words for gunpowder items came from Chinese. Saltpeter was called "Chinese snow." Fireworks were "Chinese flowers." Rockets were "Chinese arrows." Europeans also had trouble getting saltpeter, which was common in China. The similarities between early European cannons and Chinese ones also suggest direct knowledge transfer.

Middle East

The Muslim world learned about gunpowder between 1240 and 1280. By then, Hasan al-Rammah wrote recipes for gunpowder in Arabic. He also described how to clean saltpeter and make gunpowder incendiaries. Early Muslim sources suggest the Mongols brought gunpowder knowledge from China. Al-Rammah used terms that came from Chinese sources.

Early Arab texts called saltpeter "Chinese snow." Fireworks were "Chinese flowers," and rockets were "Chinese arrows." Persians called saltpeter "Chinese salt."

Al-Rammah's gunpowder recipe had a lot of saltpeter (68% to 75%). This is very explosive, but he didn't mention using it for explosions. His book, The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices, mentioned fuses, fire bombs, fire lances, and even an early torpedo. This torpedo was called the "egg which moves itself and burns."

Hasan al-Rammah was the first Muslim to describe how to clean saltpeter using chemical processes. This was a clear method for making pure saltpeter.

Some historians say fire lances were used in battles between Muslims and Mongols in 1299 and 1303.

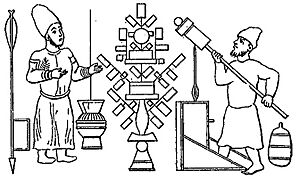

The oldest surviving document about cannons in the Islamic world is an Arabic manuscript from the early 1300s. It shows gunpowder weapons like arrows, bombs, fire tubes, and fire lances or early guns. The manuscript describes a weapon called a midfa. It used gunpowder to shoot projectiles from a tube. Some think this was a cannon. But the term midfa was also used for flamethrowers and fire lances. Clear accounts of metal-barrel cannons in the Islamic world don't appear until 1365.

Cannons were definitely used by the Mamluks by 1342. Cannons were also used by Moors at the siege of Algeciras in 1343. A metal cannon firing an iron ball was described between 1365 and 1376.

Europe

One common idea is that gunpowder came to Europe along the Silk Road through the Middle East. Another idea is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the early 1200s. Some say Chinese firearms were used by Mongols against Europeans in 1241.

The earliest European mentions of gunpowder are in Roger Bacon's book Opus Majus from 1267. He talks about a firecracker toy. He describes a small device that makes a horrible sound and a bright flash. Some think another book by Bacon had a secret gunpowder recipe. But this is debated.

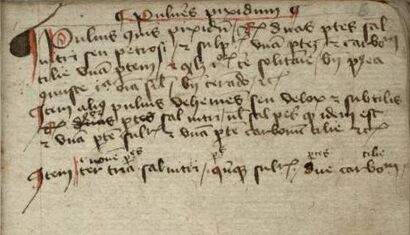

The oldest written recipes for gunpowder in Europe are from between 1280 and 1300. They are in a book called Liber Ignium, or Book of Fires. One recipe for "flying fire" uses saltpeter, sulfur, and resin. It says when put in a hollow wood, it "flies away suddenly and burns up everything." Another recipe for "thunder" uses sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter. This text was likely translated from Arabic.

The earliest known European picture of a gun appeared in 1326. It shows a gun with a large arrow coming out of it. The user is lighting it with a stick. In the same year, the city of Florence ordered metal cannons. In the next year, a record from Turin mentioned paying for a device to shoot lead pellets. A bronze gun from Mantua from 1322 was 16.4 cm long and weighed about 5 kg.

The 1320s seem to be when guns really took off in Europe. Guns spread quickly across Europe from then on. By 1341, the town of Lille had a "tonnoire master," for an arrow-shooting gun. In 1346, cannons were used at the Battle of Crécy. By 1350, cannons were "as common and familiar as other kinds of arms."

By the late 1300s, European and Ottoman guns started to be different from Chinese guns. They became larger artillery pieces. By the end of the 1300s, European guns grew bigger and started to break down forts.

Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, cannons were used by the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1352. Within ten years, the Khmer Empire had a lot of gunpowder. By the end of the 1300s, firearms were also used in Đại Việt.

The Mongol invasion of Java in 1293 brought gunpowder technology to the Nusantara islands. The knowledge of making gunpowder weapons was known after this failed invasion. Early firearms, like the pole gun, were used in Java by 1413. But "true" firearms came later, after the mid-1400s. Muslim traders, probably Arabs, brought them.

After the Portuguese captured Malacca in 1511, a new type of firearm appeared. It was a mix of local and Portuguese designs. Saltpeter was collected from large piles of dung in villages. The Dutch later banned owning or making gunpowder.

India

Gunpowder technology likely arrived in India by the mid-1300s. It might have been introduced earlier by the Mongols. The large Mongol Empire helped Chinese technology spread to Mongol-controlled parts of India. The Mongols used Chinese gunpowder weapons during their invasions of India.

In 1258, a Mongol ruler's envoy saw a dazzling pyrotechnics show in Delhi. The first gunpowder device from China in India was a rocket called the "hawai" (or "ban"). It was used in war from the mid-1300s. The Delhi sultanate and the Bahmani Sultanate used them well.

Firearms called top-o-tufak were in the Vijayanagara Empire of Southern India by 1366. By 1442, guns were clearly present in India. From then on, gunpowder warfare was common in India. Muslim and Hindu states in the south had advanced artillery. This was because they had contact with Turkey and Arab countries by sea. They imported their gunners and artillery from these places.

Korea

Korea had cannons by 1373. A Korean mission asked China for gunpowder for their ships' artillery. Korea didn't make its own gunpowder until 1374–76. In the 1300s, a Korean scholar named Ch'oe Mu-sŏn learned how to make it after visiting China. He bribed a merchant for the recipe. In 1377, he learned how to get potassium nitrate from soil. He then invented the juhwa, Korea's first rocket. Later, singijeons, Korean arrow rockets, were developed. Korea also started making cannons in 1377.

The multiple rocket launcher called hwacha ("fire cart") was developed in Korea by 1409. Its inventors included Yi To and Ch'oe Hae-san. The first hwachas didn't fire rockets. They used bronze guns that shot iron darts. Rocket-launching hwachas were developed in 1451. This "Munjong Hwacha" could fire 100 rocket arrows or 200 small bullets at once. By the end of 1451, hundreds of hwachas were used across Korea.

Naval gunpowder weapons were quickly used by Korean ships. They fought Japanese pirates in 1380 and 1383. By 1410, 160 Korean ships had artillery. Mortars firing thunder-crash bombs were used. Four types of cannons were mentioned: chonja, chija, hyonja, and hwangja. These cannons usually shot wooden arrows with iron tips, but sometimes stone and iron balls.

Japan

Firearms were known in Japan around 1270. They were proto-cannons from China, which the Japanese called teppō ("iron cannon"). Not many hand guns reached Japan. However, Japanese samurai used Fire lances in the 1400s. The first fire lances in Japan were recorded in 1409. Gunpowder bombs like Chinese explosives were used in Japan from at least the mid-1400s.

The first cannon in Japan was recorded in 1510. A Buddhist monk showed Hōjō Ujitsuna an iron cannon he got in China. Firearms were not used much in Japan until Portuguese matchlocks arrived in 1543. During the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), the Japanese used matchlock firearms effectively.

Africa

In Africa, the Adal Empire and the Abyssinian Empire used gunpowder weapons during the Adal-Abyssinian War. The Adalites were the first African power to use cannons. They imported them from Arabia and the wider Islamic world. Later, the Portuguese Empire supplied and trained the Abyssinians with cannons and muskets. The Ottoman Empire sent soldiers and cannons to help Adal. This war showed that firearms like the matchlock musket, cannon, and arquebus were better than traditional weapons.

One historian, Ernest Gellner, said that the gun and the book helped the Somali people and the Amhara people control large areas in Africa. This was true even though they weren't the largest groups.

Guns Get Better: Early Modern Warfare

Stronger Cannons in China

Gun development continued in China under the Ming dynasty. The founder, Zhu Yuanzhang, was successful partly because he used guns well.

Most early Ming guns weighed only two to three kilograms. "Large" guns weighed about seventy-five kilograms. Ming sources say these guns shot stones and iron balls. They were mainly used against people, not to damage ships or walls. They weren't very accurate and had a range of only about 50 paces.

Despite their small size, some Ming gun designs followed world trends. The length of the gun barrel compared to its opening grew, similar to European guns. "Corning" gunpowder (making it into grains) was developed by 1370 for land mines. This made gunpowder more powerful. It was likely used in guns too. Around the same time, Ming guns started using iron ammunition instead of stone. Iron is heavier and makes guns more powerful.

The Ming also created rocket launchers called "wasp nests." These were made for the army in 1380.

The best Chinese cannons before European weapons arrived in the 1500s were the "great general cannon" and the "great divine cannon." The great general cannon weighed up to 360 kilograms and fired a 4.8 kilogram lead ball. The great divine cannon could weigh up to 600 kilograms. It could fire several iron balls and many iron shots at once. These were the last Chinese cannon designs before European ones were copied.

China didn't make larger siege weapons like other parts of the world. This might be because traditional Chinese walls were very thick. Even modern artillery had trouble breaking them. Also, larger guns weren't very useful against China's main enemies: horse nomads.

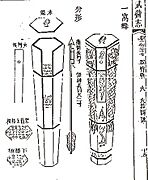

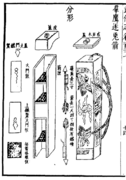

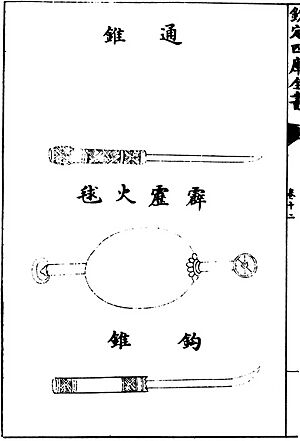

-

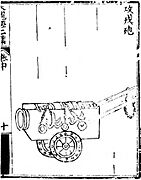

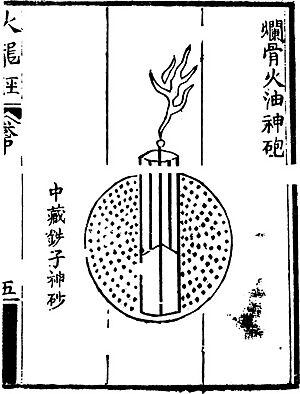

A picture of a bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon" from the Huolongjing.

-

A seven-barreled organ gun with two smaller guns on a carriage. From the Huolongjing.

-

A 'barbarian attacking cannon' from the Huolongjing. Chains helped control its kickback.

-

An "awe-inspiring long range cannon" from the Huolongjing.

-

A picture of the "crouching tiger cannon" from the Huolongjing.

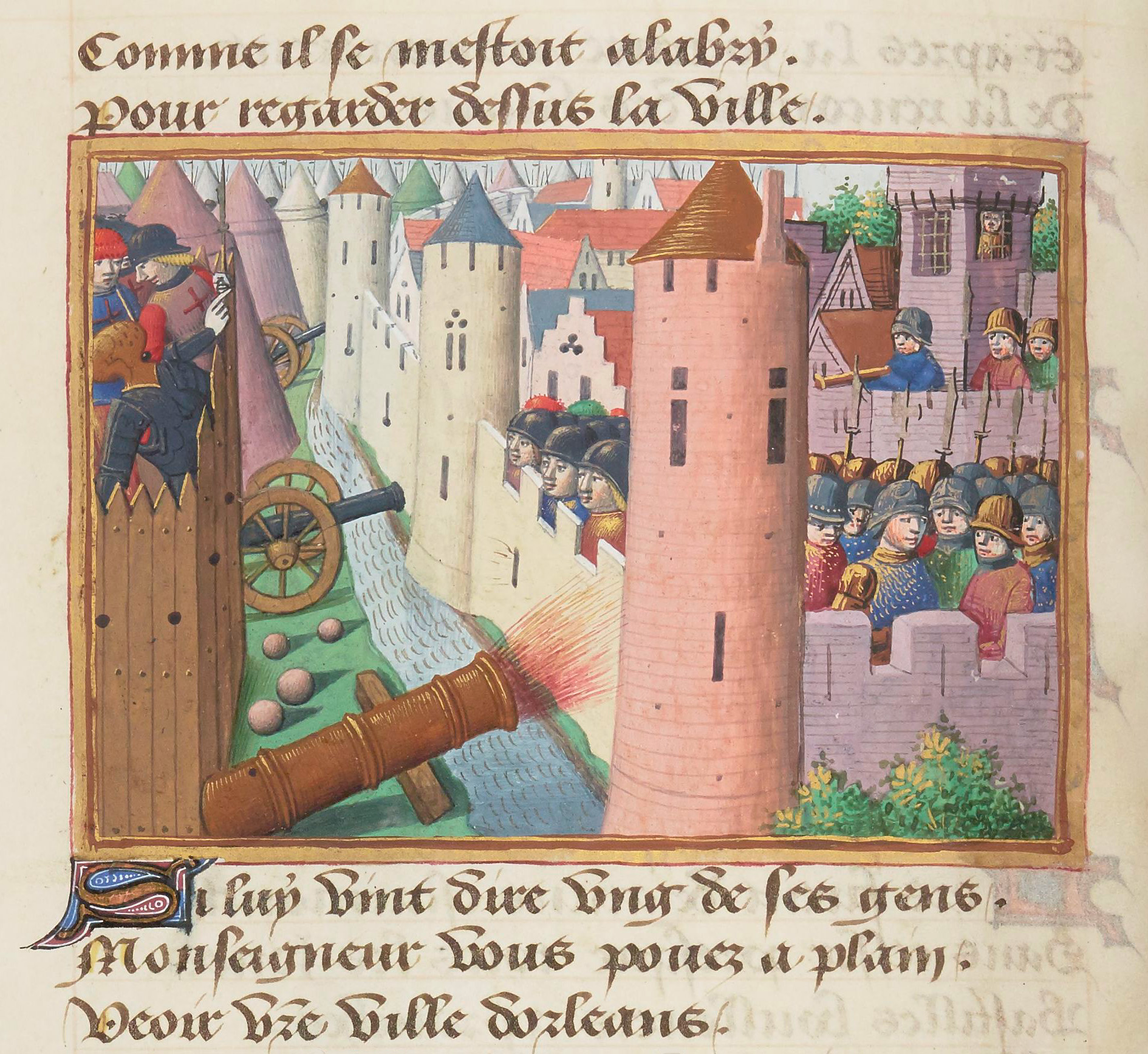

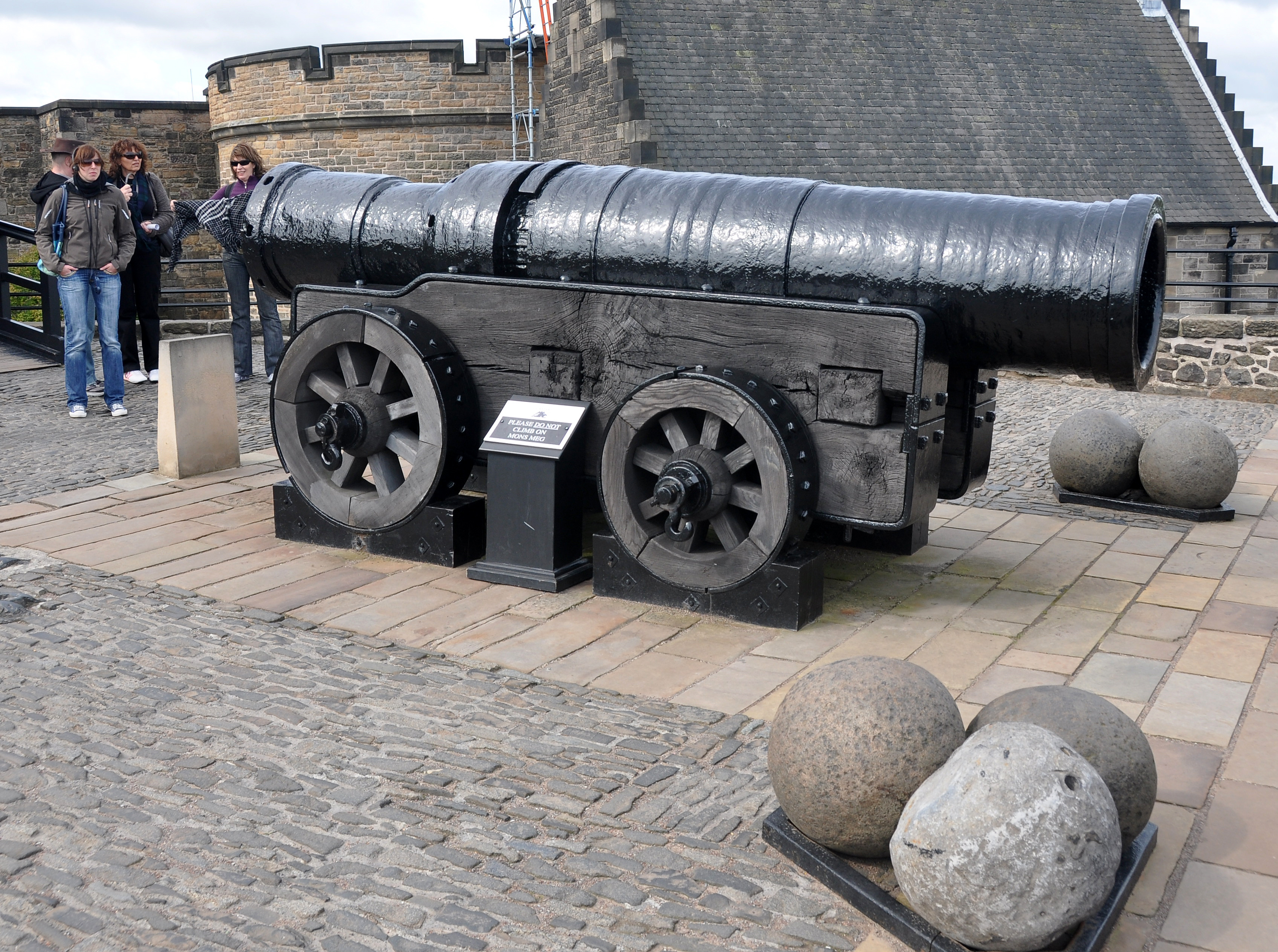

Huge Cannons in Europe

Large artillery pieces started to be developed by Burgundy. This duchy became very powerful in the 1300s and was great at inventing new siege weapons. The Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold, used big guns effectively. He supported research and development in gunpowder weapons. He hired more cannon makers than any European ruler before him.

Before 1370, most European guns weighed about 9–14 kg. But in 1375, during the Hundred Years War, guns weighing over 900 kg were used. These fired stone balls weighing over 45 kg. Philip used large guns to help the French capture a fortress in 1377. These guns fired much larger projectiles than ever before. They broke down city walls, starting a new age of artillery warfare.

Europe began a race to build bigger artillery. By the early 1400s, both French and English armies had large cannons called bombards. These weighed up to 5 tons and fired balls weighing up to 136 kg. The artillery used by Henry V of England in the 1415 and 1419 sieges helped break French forts. Artillery also helped French forces win under Joan of Arc in 1429.

These weapons completely changed European warfare. A hundred years earlier, it was very hard to capture a castle. But by the 1400s, European walls fell regularly.

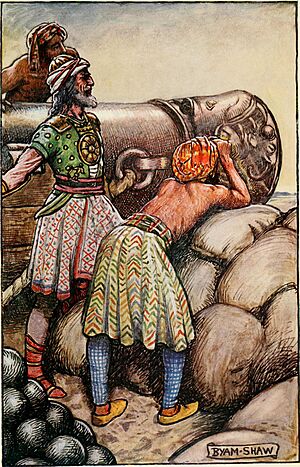

The Ottoman Empire also developed its own artillery. Mehmed the Conqueror wanted large cannons to conquer Constantinople. A Hungarian engineer made him a 6-meter long cannon. It needed hundreds of pounds of gunpowder to fire. During the siege of Constantinople, dozens of other large cannons bombarded the city's walls for 55 days. Despite a strong defense, the city's forts were overcome.

Forts Change to Fight Cannons

Because of gunpowder artillery, European forts started to change. By the mid-1400s, they had lower and thicker walls. Cannon towers were built with rooms where cannons could fire from slits. But this had problems. Cannons fired slowly, made loud noises, and produced bad fumes. Gun towers also limited how many cannons could be placed.

The star fort, also called the bastion fort, became popular in Europe in the 1500s. It was developed in Italy. The Florentine engineer Giuliano da Sangallo created a full defensive plan using these forts.

The main feature of the star fort was its angled bastions. Each bastion was placed to support its neighbor with deadly crossfire. This covered all angles, making them very hard to attack. Artillery on the flanks could fire along the walls, protecting against attacks. Artillery on the bastion platform could fire straight ahead. This overlapping fire was the biggest advantage of the star fort. As a result, sieges lasted longer and were harder to win. By the 1530s, the bastion fort was the main type of defense in Italy.

Outside Europe, the star fort helped Europeans expand. Small European armies could hold out against much larger forces. Wherever star forts were built, local people had great difficulty removing the European invaders.

In China, Sun Yuanhua suggested building angled bastion forts. This would help cannons support each other better. Some officials built two bastion forts in their home county. These helped fight off an attack in 1638. By 1641, there were ten bastion forts in that county. But before they could spread further, the Ming dynasty fell in 1644. The new Qing dynasty was usually attacking, so they didn't need these forts as much.

New Handheld Guns: Arquebus and Musket

The arquebus was a firearm that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the early 1400s. Its name comes from a German word meaning "hook gun." Early arquebuses were defensive weapons mounted on German city walls. But by the late 1400s, they became handheld firearms. Heavier versions, called "muskets," appeared in the early 1500s. These needed a Y-shaped support to fire.

The musket could shoot through all types of armor at the time. This made armor less useful, and also made the heavy musket less necessary. The musket and arquebus were similar, but the musket was larger and stronger. The term "musket" remained in use until the 1800s.

The exact date the matchlock firing system appeared is debated. The first mentions of arquebuses used by the Ottoman army are from 1394 to 1465. In Europe, a shoulder stock (like on a crossbow) was added to the arquebus around 1470. The matchlock mechanism appeared just before 1475. The matchlock arquebus was the first firearm with a trigger. It was also the first portable shoulder gun.

Matchlock became a common name for the arquebus after this system was added. Before matchlocks, handguns were fired from the chest. One hand held the gun, and the other used a hot stick to light the gunpowder. The matchlock changed this. It had a clamp that held a smoldering rope (the match). A trigger lowered the match into a pan, lighting the priming powder. This flash then ignited the gunpowder in the barrel, shooting the bullet out.

Matchlocks allowed users to aim with both hands, which was a big advantage. But they were also tricky to use. The match had to be removed while loading. Sometimes the match would go out, so both ends were kept lit. The process was so complex that a 1607 manual listed 28 steps to fire and load the gun. In 1584, a Ming general made an 11-step song to help soldiers practice. Reloading a gun in the 1500s took 20 seconds to a minute in perfect conditions.

The arquebus was used by the Spanish and Portuguese as early as 1472. The Mamluks were against using gunpowder weapons at first. They criticized the Ottomans for using them. But eventually, the Mamluks were ordered to train with arquebuses in 1489. In 1514, an Ottoman army with arquebuses defeated a much larger Mamluk force.

The arquebus became a common infantry weapon in the 1500s because it was cheap. It also needed less training. While a bow took years to master, an arquebusier could be trained in just two weeks.

In the early 1500s, the larger musket appeared. The heavy musket needed a fork rest to fire. But it could shoot through the best armor from 180 meters away. It could hit regular armor at 365 meters and an unarmed person at 548 meters. However, both the musket and arquebus were very inaccurate beyond 90 to 185 meters. A smoothbore musket often couldn't hit a person-sized target past 73 meters.

This made the smoothbore musket worse than a bow in some ways. An average Mamluk archer could hit targets 68 meters away and shoot six to eight arrows per minute. A 1500s matchlock fired one shot every few minutes. Misfires happened up to half the time. But firearms could penetrate armor better and needed less training. By the 1590s, archers were mostly replaced in European warfare. This was partly due to new tactics like "volley fire." By this time, gunners made up to 40% of European infantry.

As the musket's benefits became clear, it was quickly adopted across Eurasia. By 1560, even Chinese generals praised the new weapon. General Qi Jiguang wrote in 1560: "It is unlike any other of the many types of fire weapons. In strength it can pierce armor. In accuracy it can strike the center of targets... The arquebus is such a powerful weapon and is so accurate that even bow and arrow cannot match it, and nothing is so strong as to be able to defend against it."

Other East Asian powers, like Đại Việt, also quickly adopted the matchlock musket. Đại Việt was thought to make the best matchlocks in the world in the 1600s. European observers said Vietnamese matchlocks could pierce several layers of iron armor and kill multiple men with one shot. They also fired quietly for their size.

Gunpowder in History: The "Gunpowder Empires"

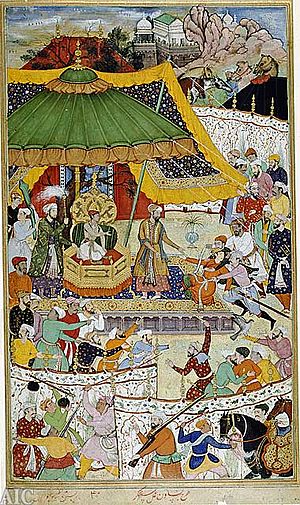

The term "Gunpowder Empires" usually refers to the Islamic Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires. This phrase was first used by Marshall Hodgson in his book The Venture of Islam (1974).

Hodgson used the term for these three Islamic states. He said they were different from earlier unstable groups of Turkic clans. They were "military patronage states" with three main features:

- They had their own strong laws.

- The whole state acted like one military force.

- All money and cultural resources belonged to the main military families.

These empires grew from Mongol ideas of greatness. But they became stable empires only after gunpowder weapons became very important in their armies.

Historian William H. McNeill added to this idea. He said that states that could control the new artillery could "unite larger territories into new, or newly consolidated, empires."

In 2011, Douglas E. Streusand criticized this idea. He said it wasn't always accurate. He noted that these empires usually gained land before they got firearms, except for the Mughals. Also, their strong military rule often came before they got gunpowder weapons.

However, it's clear that all three of these empires got artillery and firearms early in their history. They made these weapons a key part of their military plans.

Ottoman Empire

It's not certain when the Ottomans started using firearms. Some say they used cannons since the Battles of Kosovo (1389) and Nukap (1396). They definitely used them by the 1420s. Some historians say field guns were used after the Battle of Varna (1444) and certainly in the Second Battle of Kosovo (1448). Firearms, especially grenades, were used in the 1683 siege of Vienna. The arquebus reached them around 1425.

India and the Mughal Empire

In India, bronze guns were found from Calicut (1504) and Diu (1533). By the 1600s, Indians made many different firearms. Large guns were common in places like Tanjore and Dacca. Gujarāt supplied Europe with saltpeter for gunpowder in the 1600s. Bengal and Mālwa also made saltpeter. The Dutch, French, Portuguese, and English used Chāpra to refine saltpeter.

Fathullah Shirazi (around 1582), a mechanical engineer for Akbar the Great, developed an early multi-shot gun. Shirazi's fast-firing gun had many barrels. They fired hand cannons loaded with gunpowder.

Mysorean rockets were Indian military weapons. They were the first iron-cased rockets used successfully in war. The Mysorean army used them well against the British East India Company in the 1780s and 1790s.

Indian war rockets were powerful before such rockets were used in Europe. They had bamboo rods and iron points. They were aimed and fired by lighting a fuse, but they didn't always fly straight. Mines and counter-mines with gunpowder explosives were used during the times of Akbar and Jahāngir.

Gunpowder for Building Things

Gunpowder was also used for civil engineering projects.

Digging Canals

Gunpowder was used for water engineering in China by 1541. Chen Mu used gunpowder blasting to improve the Grand Canal. He blasted rocks and then dredged the debris. In Europe, gunpowder was used to build the Canal du Midi in Southern France. It was finished in 1681. It connected the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean. Another big user of black powder was the Erie Canal in New York. It was 585 km long and took eight years to build, starting in 1817.

Mining for Resources

Before gunpowder, there were two ways to break large rocks: hard labor or heating them with fire and then quickly cooling them. The first record of gunpowder use in mines is from Hungary in 1627. German miners brought it to Britain in 1638. After that, its use became common.

Using gunpowder was very dangerous until the safety fuse was invented in 1831. Another danger was the thick fumes it produced. It also risked igniting flammable gas in coal mines.

Building Tunnels

Gunpowder was also used a lot in building railways. At first, railways followed the land's shape or crossed low ground with bridges. But later, railways used many cuttings and tunnels. For example, a 730-meter part of the Box Tunnel in England used a ton of gunpowder per week for over two years. The 12.9 km long Mont Cenis Tunnel took 13 years to build, starting in 1857. Even with black powder, progress was only 25 cm a day until pneumatic drills sped up the work.

Gunpowder in American History

The Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, people mined caves for saltpeter to make gunpowder. This happened when supplies from Europe were stopped. Abigail Adams also reportedly made gunpowder on her family farm in Massachusetts.

The New York Committee of Safety printed essays on making gunpowder in 1776.

The Civil War

During the American Civil War, British India was the main source of saltpeter for the Union armies. This supply was threatened by the British government during the Trent Affair. The British stopped all saltpeter exports to the United States. The situation was later solved.

The Union Navy blocked the southern Confederate States. This reduced how much gunpowder could be imported. The Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau was formed to make gunpowder from local resources. While carbon and sulfur were easy to find, potassium nitrate was often made from dirt in caves, tobacco barns, and other places. Men and boys who worked in the caves were called "peter monkeys."

In November 1862, the Confederate government asked for "able bodied Negro men" to work in new nitre beds. These beds were large rectangles of rotted manure and straw. The process was designed to get saltpeter, which the Confederate army needed. The South was so desperate that one official asked people to save the contents of chamber pots for collection. In 1863, many enslaved people worked in a huge cave in Georgia. They worked by torchlight in bad conditions, hauling out and processing the "peter dirt." In South Carolina, in April 1864, the Confederate government hired 31 enslaved people to work at the Ashley Ferry Nitre Works.

Why Gunpowder Changed

In the late 1800s, new explosives like nitroglycerin, nitrocellulose, and smokeless powders were invented. These quickly replaced traditional gunpowder in most uses, both for civilians and in the military.

See Also

- Black powder substitute

- Early thermal weapons

- Hand cannon

- Green mix

- Gunpowder warfare

- Huolongjing

- Jiao Yu

- Jixiao Xinshu

- Meal powder

- Technology of Song Dynasty

- Wubei Zhi

- Wujing Zongyao

Images for kids

-

Vase-shaped gun of Mantua (image produced 1869), no longer existing.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |