Wujing Zongyao facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wujing Zongyao |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 武經總要 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 武经总要 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The Wujing Zongyao (Chinese: 武經總要) is an important Chinese book about military skills. Its name means Complete Essentials for the Military Classics. This huge collection of knowledge was written between 1040 and 1044.

The book was put together during the Northern Song dynasty by three main people: Zeng Gongliang, Ding Du, and Yang Weide. Their work greatly influenced many military writers who came after them. Emperor Renzong of Song supported the creation of this book and even wrote its introduction.

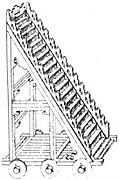

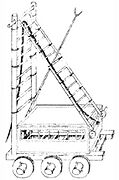

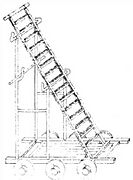

The Wujing Zongyao covers many topics. It talks about everything from large warships to different types of catapults. It holds the oldest known written recipes for gunpowder. This early gunpowder was made from saltpeter, sulphur, and charcoal, plus other ingredients.

Besides gunpowder recipes, the book also describes many gunpowder weapons. These include fire arrows, incendiary bombs, and smoke bombs. It also explains an early kind of compass. Plus, it has the oldest picture of a Chinese flamethrower. This flamethrower used a special pump to shoot a steady stream of fire.

History of the Wujing Zongyao

The Wujing Zongyao was created because Emperor Renzong of Song (who ruled from 1022 to 1063 AD) was worried. Many government officials did not know much about military history or tactics. The book was also a response to the Song dynasty's war with the Tangut people from Western Xia.

A group of smart people worked from 1040 to 1044 to write the Wujing Zongyao. Their goal was to gather all known military knowledge. They wanted to share it with more government officials. Zeng Gongliang was the main editor. He was helped by the astronomer Yang Weide and the scholar Ding Du. After five years, the book was finished. Emperor Renzong himself wrote the introduction.

Many parts of the Wujing Zongyao were copied from older books. This was a common practice back then. The original authors were often not named. During the Song dynasty, two other books were added to the Wujing Zongyao. These were the Xingjun xuzhi and the Baizhan qifa.

The Wujing Zongyao was one of 347 military books listed in the History of Song. This history book was written in 1345 AD. Out of all those military books from the Song period, only the Wujing Zongyao and a few others have survived. The main copy of the Wujing Zongyao was kept secret in the Imperial Library. Only a few trusted government officials were allowed to read it. This was to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

The original copy of the Wujing Zongyao was lost during the Jin–Song Wars. This happened when the Jurchens attacked and took over the Northern Song capital of Kaifeng in 1126 AD. Luckily, a few copies survived. A new version was printed in 1231 AD during the Southern Song dynasty.

Later, during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD), another book was published in 1439 AD. It contained parts of the 1231 Wujing Zongyao. The complete Wujing Zongyao was reprinted in 1510 AD. This 1510 version is the oldest full copy we have today. Experts believe it is very similar to the original.

The Xu Wujing Zongyao (meaning "Continuation of Wujing Zongyao") was written later. It came out in the late Ming dynasty. This book mainly focused on how armies should be arranged and deployed. It was written by Fan Jingwen. He felt that the existing Wujing Zongyao copies were old-fashioned. They did not include new technologies and strategies. Only one copy of the Xu Wujing Zongyao still exists today.

In the 3rd century, a Chinese engineer named Ma Jun invented the south-pointing chariot. This was a wheeled vehicle. It used special gears to make a small figure always point south.

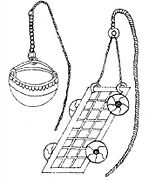

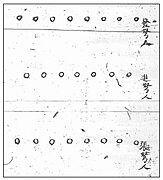

The authors of the Wujing Zongyao thought this chariot design was lost. However, they described a new way to find directions. This was the 'south pointing fish'. It was a heated iron or steel object shaped like a fish. This fish was then floated in a bowl of water. The Wujing Zongyao explains how to make and use it:

When soldiers faced cloudy weather or dark nights, and could not tell directions, they would let an old horse lead them. Or they would use the south-pointing carriage, or the south-pointing fish to find directions. The carriage method is not known anymore. But for the fish method, a thin piece of iron is cut into a fish shape. It should be two inches long and half an inch wide, with a pointed head and tail. This is heated in a charcoal fire until it is red-hot. Then, it is taken out by the head with iron tongs. It is placed so its tail points north. In this position, it is cooled with water in a basin. Its tail should be slightly underwater. It is then kept in a sealed box. To use it, a small bowl of water is placed in a calm spot. The fish is laid as flat as possible on the water. Its head will then point south.

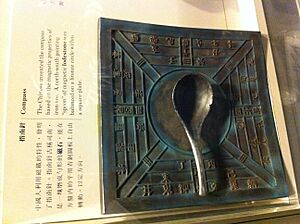

Later in the Song dynasty, the compass was used for sailing. Decades after the Wujing Zongyao was written, Shen Kuo (1031–1095 AD) described the first truly magnetized compass needle. This was in his book Dream Pool Essays (1088 AD). With better compasses using lodestone, the 'south pointing fish' was used less often.

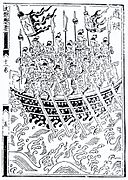

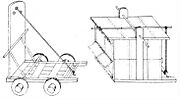

The Wujing Zongyao's detailed drawings of warships were very important. They influenced many later books about naval warfare. For example, the Wubei Zhi from around 1628 used these illustrations. Even Japanese naval books in the 1700s used pictures from the Wujing Zongyao.

The Wujing Zongyao divides Chinese warships into six types:

- Tower ships (lou chuan)

- Combat or war junks (dou xian or zhan xian)

- Covered swoopers (meng chong)

- Flying barques (zou ge)

- Patrol boats (you ting)

- Sea hawk ships (hai hu)

This way of classifying warships was used in naval books for many centuries.

-

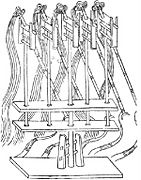

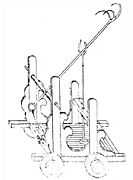

A "tower" ship with a traction-trebuchet on its top deck, from the Wujing Zongyao

Gunpowder and Weapons

Gunpowder Weapons

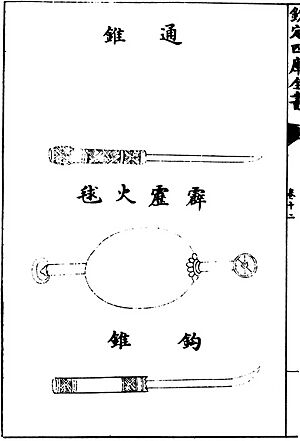

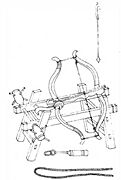

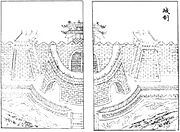

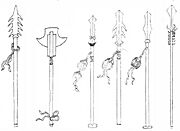

The Wujing Zongyao gives detailed descriptions of many gunpowder weapons. These include fire-starting projectiles, smoke bombs, fire arrows, and grenades. It talks about incendiary projectiles. These were filled with low-nitrate gunpowder. They were launched from catapults or dropped from city walls onto attackers.

Examples of these fire-starting weapons include the "swallow-tail" incendiary (燕尾炬) and the flying incendiary (飛炬). The swallow-tail incendiary was made of straw dipped in fat or oil. Chinese soldiers would light it and lower it onto enemy wooden structures to burn them. The flying incendiary looked similar. But it was lowered using an iron chain from a special lever on the city walls.

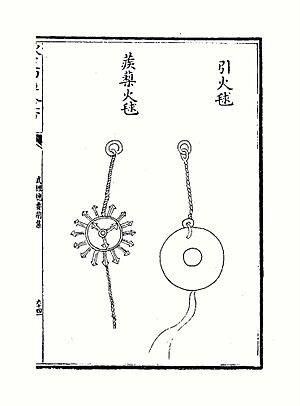

The book also describes an 'igniter ball'. This was used in battle to find the firing range. The Wujing Zongyao says:

The 'igniter ball' (yin huo qiu) is made of paper shaped like a ball. Inside, it has three to five pounds of powdered bricks. Melt yellow wax and let it clear. Then add powdered charcoal to make a paste. This paste soaks into the ball. Tie it up with hemp string. When you want to find how far something is, shoot this fire-ball first. Then other fire-starting balls can follow.

Gunpowder was also put on fire arrows (火箭) to make them incendiary. The Wujing Zongyao says fire arrows were shot from bows or crossbows. The gunpowder for fire arrows was likely a low-nitrate type. The amount of gunpowder changed depending on the type of bow. The book says gunpowder could launch an arrow, but only if the crossbow was strong enough.

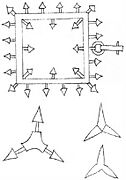

The Wujing Zongyao talks about different kinds of incendiary bombs and grenades. They used low-nitrate gunpowder. This powder was not strong enough to cause a big explosion. But it was good for starting fires. The huoqiu (火毬; "fire ball") was filled with gunpowder. It was launched using a trebuchet. When it hit, the huoqiu would start a fire among the enemy army.

Chinese bombs like the thunder clap bomb, or pili pao, used more gunpowder. The gunpowder mix for a bomb was put inside a strong container. This held in the expanding gas, making stronger explosions. The thunder clap bomb was made with a bamboo container.

In the Wujing Zongyao, it's sometimes hard to tell the difference between a bomb and a grenade. Back then, the Chinese usually did not sort gunpowder weapons by how they were delivered. One rare exception is the shoupao, or hand bomb. This was like a hand grenade.

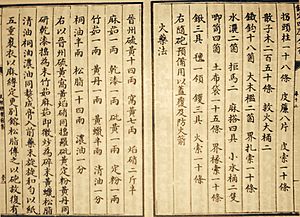

Gunpowder Formulas

Gunpowder was invented by Chinese alchemists before the Wujing Zongyao. This happened in the 800s. Early mentions of gunpowder are in a Daoist book from around 850. Gunpowder was used in Chinese warfare as early as the 900s. It was in fire arrows and fuses for the Chinese two-piston flamethrower.

But the Wujing Zongyao was the first to show the exact chemical recipes for early Chinese gunpowder. The book has three gunpowder formulas:

- One for an explosive bomb launched from a trebuchet.

- Another for a similar bomb with hooks. These hooks would grab onto wooden structures and set them on fire.

- A third recipe for a poison-smoke bomb used for chemical warfare.

The Wujing Zongyao's first gunpowder recipe for these bombs had about 55% potassium nitrate. It also had about 19% to 26% sulfur and 23% to 25% carbon (from charcoal).

To make gunpowder, you first grind and mix sulfur, saltpeter, charcoal, pitch, and dried lacquer. Then, tung oil, dried plants, and wax are mixed to make a paste. The paste and powder are combined and stirred carefully. The mixture is then put inside a paper container, wrapped, and tied with hemp string. Steps are taken to keep the gunpowder from getting wet.

Here are some of the ingredients listed in the book for these early gunpowder mixtures:

Fireball formula

|

Caltrop fireball formula

|

Inner ball |

Outer coating |

Poisonous smoke ball formula

|

Inner ball |

Outer coating |

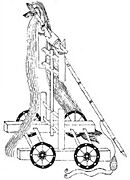

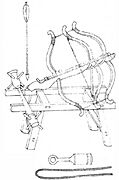

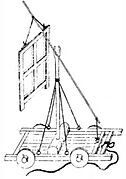

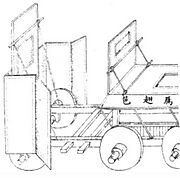

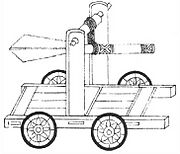

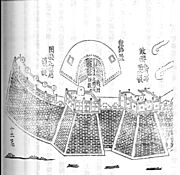

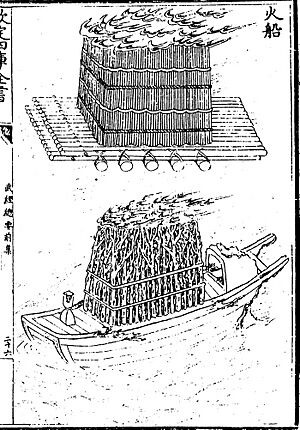

Double-Acting Piston Flamethrower

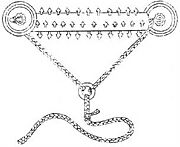

The Wujing Zongyao describes a flamethrower that used a special pump. This pump had two pistons. It could shoot a steady stream of fire. The first Chinese battle to use this type of flamethrower was the Battle of Langshan Jiang in 919 AD. In this battle, the naval fleet of the Wenmu King defeated the fleet of the Kingdom of Wu. He used 'fire oil' (huo yóu) to burn the enemy ships. This was one of the earliest uses of gunpowder in warfare. A slow-burning fuse was needed to light the flames.

The Chinese had been using piston syringes since the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD). But the Wujing Zongyao was the first to provide a drawing and a detailed explanation of how this flamethrower worked. The book describes the flamethrower in detail:

On the right is the petrol flamethrower (fierce fire oil-shooter). The tank is made of brass, and stands on four legs. From its top, four tubes go up to a horizontal cylinder above. They are all connected to the tank. The ends of the cylinder are wide, and the middle is narrow. At the tail end, there is a small opening, like a millet grain. The head end has two round openings, 1½ inches wide. On the side of the tank, there is a hole with a small tube for filling, which has a cover. Inside the cylinder, there is a piston-rod wrapped with silk floss. The head of the rod is wrapped with hemp waste about ½ inches thick. The two connecting tubes are alternately closed, and the machine works this way. The tail has a horizontal handle (the pump handle). In front of it, there is a round cover. When the handle is pushed in, the pistons close the tube openings one by one.

Before use, the tank is filled with a bit more than three catties of oil using a spoon through a filter. At the same time, gunpowder is put into the ignition chamber at the head. When you want to start the fire, you touch a heated branding iron to the ignition chamber. The piston-rod is pushed fully into the cylinder. Then the person at the back is told to pull the piston rod fully back and pump it as fast as possible. This makes the oil (petrol) come out through the ignition chamber and shoot out as a blazing flame.

The text also gives instructions on how to maintain and fix the flamethrowers:

When filling, use the bowl, spoon, and filter. For lighting, there is the branding iron. For keeping the fire going, there is the container. The branding iron is sharp like an awl so it can clear blocked tubes. There are tongs to pick up glowing fire. There is a soldering iron to fix leaks. If the tanks or tubes crack and leak, they can be mended with green wax. In total, there are 12 tools, all made of brass except the tongs, branding iron, and soldering iron. Another way is to put a brass gourd-shaped container inside a large tube. Below it has two feet, and inside there are two small feet connected to them (all made of brass). There is also the piston. The way of shooting is as described above. If the enemy attacks a city, these weapons are placed on the great ramparts, or in outer defenses. This way, many attackers cannot get through.

Images for kids

-

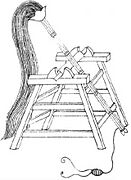

A bird with an incendiary around its neck.

See also

- History of the Song dynasty

- Gunpowder warfare

- Technology of the Song dynasty

- Jiao Yu

- Battle of Tangdao

- Battle of Caishi

- Huolongjing, a Chinese military book from the mid-1300s.

- Jixiao Xinshu, a Chinese military manual written in the 1560s and 1580s.

- Wubei Zhi, a Chinese military book compiled in 1621.

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |