Economy of the Song dynasty facts for kids

The Song dynasty (960–1279) had one of the most successful economies in the world. Unlike earlier times, the Song government let markets play a big role. This helped China's wealth grow to about three times that of Europe in the 1100s. Even though the Song faced many invasions and lost control of northern China in 1127, their economy thrived.

During this time, cities grew, and different regions became good at making specific things. This created a strong national market. The population and people's income increased steadily. New technologies also appeared, like movable type printing and better seeds for crops. They also developed gunpowder, water-powered clocks, and used coal for industry. Iron and steel production improved, and canals became more efficient. China produced about 100,000 tons of steel and had cities with millions of people.

Trade with other countries grew a lot. Chinese merchants invested in ships and traded as far as East Africa. The Song dynasty also invented the world's first paper money. This paper money, like Jiaozi and Huizi, was used widely. A single tax system and good roads and canals helped create a nationwide market. Different regions making specialized goods made the economy more efficient. Even though a lot of government money went to the military, taxes from growing businesses helped fill the treasury. This also encouraged people to use money more.

The government still managed the economy, but less strictly than before. However, it kept control over important goods like tea, salt, and gunpowder ingredients. These changes made some historians call Song China an "early modern" economy. This happened centuries before similar changes in Western Europe. Sadly, many of these economic gains were lost in the later Yuan and Ming dynasties. These later dynasties went back to a more controlled economy.

Contents

Farming and Food Production

Farming land grew a lot during the Song dynasty. The government encouraged people to farm new, unused lands. Anyone who cleared new land and paid taxes could keep it forever. Because of this, farmed land reached about 48 million hectares. This amount was not surpassed by later dynasties.

Irrigation systems also improved greatly. A statesman named Wang Anshi introduced a law in 1069 to expand irrigation. By 1076, about 10,800 irrigation projects were finished. These projects watered over 36 million mu (a Chinese land unit) of land. Big projects included cleaning the Yellow River and creating artificial land in the Lake Tai area. As a result, crop production in China tripled. Farmers produced about 2 tan (about 110 pounds) of grain per mu. This was much more than in earlier dynasties.

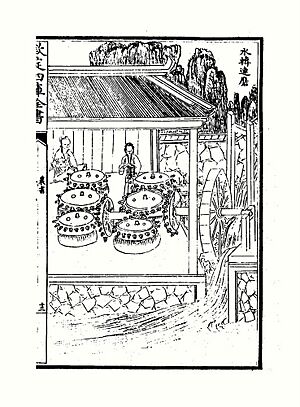

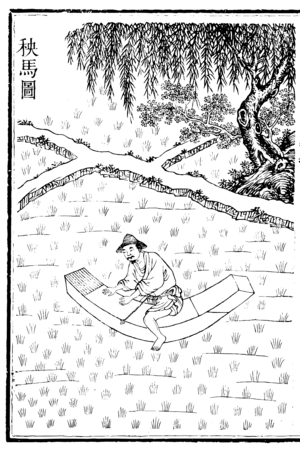

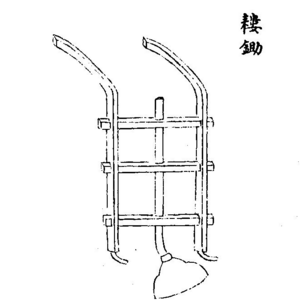

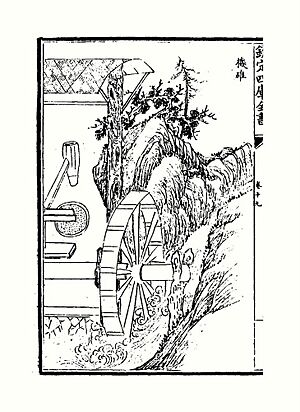

The Song economy also improved farm tools, seeds, and fertilizers. Farmers used better plows, including a strong steel plow for clearing wasteland. They also invented a "seedling horse" tool to help plant rice. Bamboo water wheels were used to lift water from rivers for irrigation. Some farmers even used three-stage water wheels to lift water very high.

New high-yield seeds were brought to China. These included Champa rice from Vietnam, Korean yellow paddy, Indian green peas, and Middle Eastern watermelons. Song farmers also understood the importance of using night soil (human waste) as fertilizer. They knew it could turn poor land into fertile farmland.

Cash Crops and Trade

The Song period saw a quick growth in cash crops. These were crops grown to be sold, like tea, sugar, mulberry, and indigo.

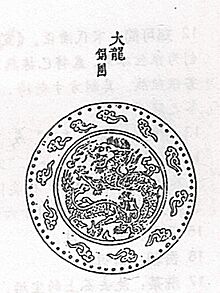

Tea became one of the seven common household items. Tea houses became very popular in cities. Because of this, tea farms grew three times larger than in the Tang period. Foreigners also bought a lot of Chinese tea, especially from Sichuan. Tea production was very centralized, with a few areas producing most of it. The Beiyuan Plantation in Fujian grew special "dragon tea cakes" for the emperor.

Cotton was brought from Hainan to central China. It was used to make cloth called "jibei." Hemp was also widely grown for textiles. Farmers in Suzhou specialized in raising silkworms to produce silk.

Sugarcane cultivation was famous in the Lake Tai valley. A writer named Wang Zhuo wrote a detailed book in 1154 about growing sugarcane and making sugar. This was the first book about sugar technology in China. As cities grew, valuable vegetable farms appeared in the suburbs. These farms could support many more people per mu than grain farms.

Business and Trade Networks

While large government and private companies were important, many small businesses also thrived. There was even a large black market, especially after the Jurchens took northern China. Small pottery shops, oil presses, and wine-making businesses were common.

Rural families who sold extra farm goods could buy more charcoal, tea, and oil. They could also start other small businesses. Farmers in Suzhou often raised silkworms, while those in Fujian, Sichuan, and Guangdong grew sugarcane. To help rural areas, new tools and irrigation techniques were very important. China's large irrigation system needed many wheelwrights to make waterwheels and pumps.

For clothes, wealthy people wore silk, while poorer people wore hemp and ramie. By the late Song period, cotton clothes were also used. Moving goods was easier thanks to the invention of the canal pound lock in the 10th century. This invention saved a lot of labor and allowed much larger boats to carry goods. Boats could carry up to 88 tons of cargo, which was a huge improvement.

City Jobs and Businesses

City life offered many new jobs and businesses. In Kaifeng, the capital, shopkeepers often ate out at restaurants or food stalls. Restaurants that served regional dishes were popular with merchants and officials from different parts of China. The city had many theaters, some holding thousands of people. These theaters brought huge crowds, which helped nearby businesses. Besides food, shops sold valuable items like paintings, silk, jewelry, and incense.

Government Control and Private Trade

The Song government sometimes controlled industries strictly and sometimes allowed free competition. For example, the government supported silk mills in some areas but banned private silk trade in Sichuan. The government also controlled the production and sale of tea, salt, and wine. The state's control over Sichuan tea was a main source of money for buying horses for the army. Despite political debates, government monopolies and taxes remained the main source of income. Private merchants could still make big profits from luxury goods and specialized regional products.

Global Trade

Sea trade with Southeast Asia, India, the Islamic world, and East Africa brought great wealth. While trade along the Grand Canal and rivers was huge, seaports like Quanzhou and Guangzhou were also very important. These ports connected to inland areas by canals, selling cash crops grown far from the coast. China's high demand for foreign luxury goods and spices boosted maritime trade. The shipbuilding industry grew quickly, especially in Fujian.

The Song capital at Hangzhou was connected to the seaport at Mingzhou (modern Ningbo). Many imported goods were shipped from Mingzhou to the rest of the country. Goods like pearls, ivory, frankincense, and coral came from Arab countries. Herbal medicine came from Java, and cotton cloth from Mait.

Fires were a constant threat in cities like Hangzhou. Wealthy families built large, guarded warehouses to protect goods from fires. Shipbuilding created many jobs for skilled workers. Sailors also found many opportunities as more people invested in overseas trade. Foreign merchants, especially Muslims, played a big role in China's import and export business. Chinese merchants spread their investments across several ships to reduce risk.

An observer noted that people invested in overseas trade, often making "several hundred percent" profit.

Zhu Yu's book Pingzhou Table Talks (1119) described how sea voyages were organized. Large ships could carry hundreds of people. Merchants chose a "Leader" and "Deputy Leader" for each ship. Pilots used the stars, sun, and even mud from the seabed to navigate. They also used the magnetic compass.

A resident of Hangzhou wrote in 1274 that large merchant ships could hold up to 600 passengers. Smaller ships carried up to a hundred. Foreign travelers were impressed by China's economy. The famous traveler Ibn Battuta wrote that "nowhere in the world are there to be found people richer than the Chinese."

Salaries and Wealth

Wealthy landowners were usually those who could afford to educate their sons. These sons could then become government officials. However, family wealth could decrease if it was divided among many heirs. A scholar named Yuan Cai (1140–1190) advised officials to invest their salaries. He suggested buying productive property or investing in pawn shops. He said that money invested could double in a few years.

Shen Kuo (1031–1095), a finance minister, agreed. He said that money's usefulness comes from being circulated and loaned. If money is kept hidden, its value stays the same. But if it's used in business, its value grows many times over.

Studies show that common laborers in the Song dynasty earned about 100 wen (a type of coin) a day. This was about five times what was needed to live. This was a very high living standard for that time.

Crafts and Industry

Porcelain Production

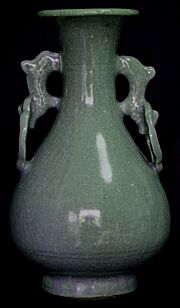

From the late Tang to early Song period, Chinese craftspeople invented true porcelain. This meant the glaze, colors, and pot itself were all made of glass-like material. Different styles of ceramics appeared, but a green-white porcelain called Qingbai ware from Jingdezhen became very famous. Jingdezhen had over 300 kilns (ovens for pottery) and 12,000 skilled workers during the Song period.

Porcelain and celadon (a type of green glaze) replaced silk as China's main export. Kilns appeared along coastal ports like Quanzhou. Quanzhou potters first copied Qingbai wares, but by the 12th century, they created their own styles. These were popular in places like Japan. However, the very best porcelain from Jingdezhen and other famous centers was mostly kept in China due to high demand.

Steel and Iron Industries

Alongside paper money, China saw the start of an "early industrial revolution." Iron production increased greatly. By 1078, China might have produced 125,000 tons of iron per year. This was much higher than in earlier dynasties.

Large amounts of charcoal were used in iron smelting, which led to cutting down many trees in northern China. But by the late 11th century, the Chinese found that bituminous coke could replace charcoal. This saved many forests. Iron and steel were used to make plows, hammers, needles, nails for ships, and chains for suspension bridges. Iron was also needed for salt and copper production. New canals connected iron and steel centers to the capital's market. This also helped international trade.

Historical records show the size of the iron industry. For example, in Hancheng, Shaanxi, 700 households were smelting iron. The government supported 200 of them with charcoal and skilled workers. In 1055, a ban on private smelting in Shaanxi was lifted. This led to a big increase in iron production. In Xuzhou in 1078, there were 36 iron smelters run by local families. Each employed hundreds of people and produced 7,000 tons of iron and steel per year.

Gunpowder Production

The Song dynasty had organized systems for getting resources. Sulfur, called 'vitriol liquid', was extracted from pyrite. It was used for medicine and to make gunpowder. The main producer of sulfur was Jin Zhou (modern Linfen). The government managed its production and sale. In 1076, the Song government had a strict control over sulfur production. They even banned selling saltpetre and sulfur to foreigners. This showed their fear that enemies like the Tanguts and Khitans might develop gunpowder weapons.

Because Jin Zhou was near the capital Kaifeng, Kaifeng became the biggest producer of gunpowder. With improved sulfur and potassium nitrate, the Chinese could use gunpowder as an explosive, not just for setting fires. The Song dynasty had large factories for making 'fire-weapons' like fire lances and fire arrows. During a war with the Mongols in 1259, the city of Qingzhou made thousands of iron-cased bombs each month. A main storage place for gunpowder and weapons at Weiyang accidentally exploded in 1280.

New Ideas in Money

Copper Coins and Receipts

The idea of paper money started in the earlier Tang dynasty. The government made copper coins the main currency. By 1085, China produced 6 billion copper coins a year. This was a huge increase compared to earlier dynasties. In 997 AD, only 800 million coins were made annually.

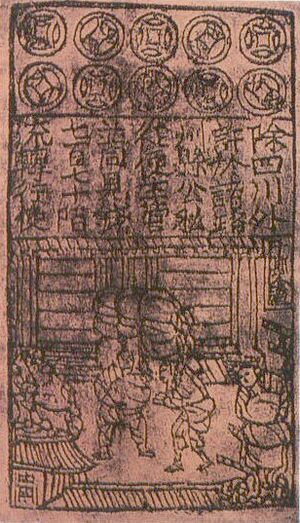

Merchants in the 800s found copper coins heavy to carry. So, they started using trading receipts from deposit shops. They would leave copper coins with wealthy families and get a receipt. This receipt could be cashed in other towns. The Song government started issuing its own receipts, mainly for the salt industry. China's first official regional paper money appeared in Sichuan in 1024.

Even with many copper coins, some mines closed. Also, a lot of copper money left the country through international trade. The Liao dynasty and Western Xia even exchanged their iron coins for Song copper coins. To stop this, the Song government tried to alloy iron coins with tin. They also tried to limit copper use in border areas. The government started using other materials for currency, like iron coins and paper banknotes.

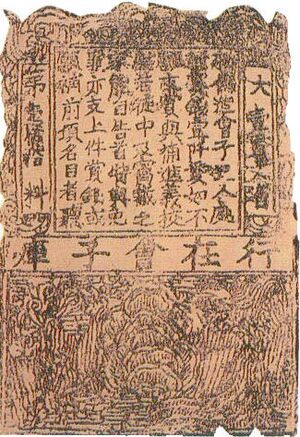

The World's First Paper Money

The government soon saw the benefits of printing paper money. They gave some deposit shops the right to issue these certificates. By the early 12th century, 26 million strings of cash coins were issued in paper money each year. By the 1120s, the government officially started printing its own paper money using woodblock printing.

The Song court had several government factories just for printing paper money. The factory in Hangzhou alone employed over a thousand workers daily in 1175. At first, paper money was only used in certain regions and for a limited time. But between 1265 and 1274, the Southern Song government created a nationwide paper currency. This money was backed by gold or silver. The value of these banknotes ranged from one string of cash to a hundred. Later dynasties also used paper money to fight against fake copper coins.

A printing plate from 1214 was found in Rehe. It produced notes worth a hundred strings of cash. This paper money had a serial number and warned that counterfeiters would be executed.

Joint Stock Companies

Merchants became more skilled and organized. Their wealth often matched that of government officials. They created new business ideas, like partnerships and joint stock companies. These companies separated the owners (shareholders) from the managers. In bigger cities, merchants formed guilds for specific products. These guilds set prices and represented merchants to the government.

The Tang dynasty had an early form of joint stock company called heben. By the Song dynasty, this grew into the douniu. This was a group of shareholders whose money was managed by jingshang, who were merchants. Investors shared in the profits, which reduced their individual risk.

A mathematician named Qin Jiushao (around 1202–1261) wrote about these companies. He described a partnership where four people invested a lot of money in a trading trip to Southeast Asia. Each person invested different amounts, but they all received a share of the profits based on their original investment.

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |