Warring States period facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Warring States period |

|

|---|---|

| c. 475–221 BC | |

|

| Warring States period | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Warring States" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 戰國時代 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 战国时代 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhànguó Shídài | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Warring States era" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Warring States period (traditional Chinese: 戰國時代; simplified Chinese: 战国时代; pinyin: Zhànguó Shídài) was a time in ancient Chinese history. It was known for many wars, but also for big changes in how the government and army worked. This period came after the Spring and Autumn period. It ended when the Qin state conquered all other states. This led to the creation of the first unified Chinese empire in 221 BC, under the Qin dynasty.

Historians have different ideas about when the Warring States period truly began. Some say 481 BC, others 403 BC. But most often, people use 475 BC, a date chosen by the famous historian Sima Qian. This era also happened during the second half of the Eastern Zhou period. However, the Chinese sovereign, known as the king of Zhou, was just a figurehead and had very little real power. The name "Warring States period" comes from a book called Record of the Warring States. This book was written much later, during the Han dynasty.

Contents

- Geography of the Warring States

- When Did the Warring States Period Begin?

- History of the Warring States

- Military Changes and Ideas

- Culture and Society

- Literature of the Period

- Economic Developments

- See also

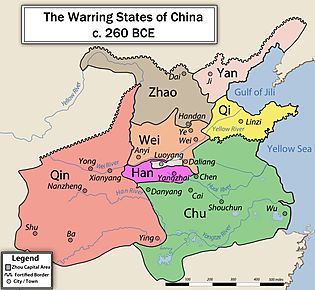

Geography of the Warring States

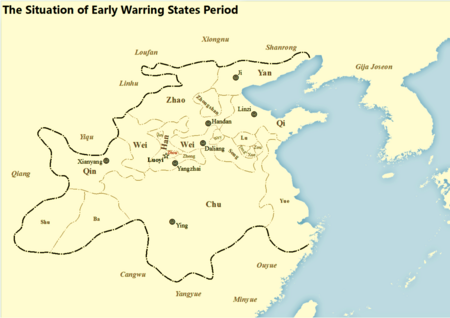

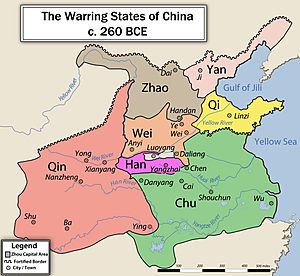

During this time, China was divided into seven main states. These were called the Seven Warring States. Let's look at where they were:

- Qin was in the far west. Its main area was the Wei River Valley. This location protected Qin from other states but also limited its early influence.

- The Three Jins were in the center. These three states were formed after the old state of Jin split apart. They were:

- Han was in the south, along the Yellow River. It controlled the paths leading to Qin.

- Wei was in the middle, in what is now eastern Henan Province.

- Zhao was the northernmost of the three. It covered parts of today's southern Hebei Province and northern Shanxi Province.

- Qi was in the east, mainly on the Shandong Peninsula.

- Chu was in the south. Its main lands were around the Han River and later the Yangtze River.

- Yan was in the northeast, near modern-day Beijing. Later, it expanded to the Liaodong Peninsula.

Besides these seven big states, some smaller ones also existed.

- The Zhou king's own land was near Luoyi.

- Yue was on the southeast coast. It was very active earlier but was later taken over by Chu.

- Zhongshan was between Zhao and Yan. Zhao eventually conquered it in 296 BC.

- Sichuan states: In the far southwest were Ba and Shu. Qin conquered these kingdoms later.

- Many other small states were satellites of the larger ones. They were eventually absorbed.

When Did the Warring States Period Begin?

The Spring and Autumn period began when the Zhou court moved east in 771 BC. The Warring States era didn't start with one single event. It was a gradual change from the many wars and takeovers that happened in the Spring and Autumn period. Because of this, there's some debate about its exact start date. Here are some ideas:

- 481 BC: Some historians say this year, as it marks the end of an important historical record called the Spring and Autumn Annals.

- 475 BC: The historian Sima Qian chose this date. It was the first year of King Yuan of Zhou's rule.

- 453 BC: This is when the state of Jin broke into three new states: Han, Zhao, and Wei. These became three of the seven main warring states.

- 403 BC: This year, the Zhou court officially recognized Han, Zhao, and Wei as independent states. This showed that the Zhou king's power was much weaker.

History of the Warring States

How the Period Started

The Eastern Zhou Dynasty started to lose its power around the 5th century BC. The Zhou kings had to rely on other states' armies instead of their own. Over 100 smaller states eventually became seven major ones: Chu, Han, Qin, Wei, Yan, Qi, and Zhao. But the rulers of these states all wanted to be completely independent. This led to many wars between 535 and 286 BC. The state that won would control all of China.

The old system of feudal states, set up by the Western Zhou dynasty, changed a lot after 771 BC. The Zhou court moved to Luoyang, and its power greatly decreased. During the Spring and Autumn period, a few states grew strong by taking over many smaller ones. These smaller states could no longer depend on the central Zhou authority for protection.

During the Warring States period, many rulers claimed the "Mandate of Heaven". This was a belief that heaven chose them to rule. They used this idea to justify conquering other states and expanding their power.

The fight for control eventually created a system where a few large states dominated. These included Jin, Chu, Qin, Yan, and Qi. Smaller states in the Central Plains became their satellites or paid tribute to them. The last years of the Spring and Autumn era were more peaceful. Jin and Chu made agreements that set their areas of influence. This peace ended when Jin split into Han, Zhao, and Wei. This created the seven major warring states.

The Splitting of Jin (453–403 BC)

The rulers of Jin had been losing power to their nobles and military commanders since the 6th century BC. This happened because Jin traditions did not allow the duke's relatives to be given land. This allowed other powerful families, like the Han, Zhao, Wei, and Zhi, to gain control.

In 453 BC, the Han, Zhao, and Wei families joined forces. They destroyed the Zhi family at the Battle of Jinyang and divided its lands among themselves. This made them the real rulers of most of Jin's territory. This split of Jin created a power vacuum. In the next 50 years, Chu and Yue expanded north, and Qi expanded south. Qin increased its control over local tribes and began to expand southwest into Sichuan.

Early Years of Conflict

The Three Jins are Recognized (403–364 BC)

In 403 BC, the Zhou court, led by King Weilie, officially recognized Zhao, Wei, and Han as independent states. This made them equal to the other major warring states.

From 405 to 383 BC, the three Jin states were united under Wei's leadership. Wei expanded in all directions. A key leader was Marquess Wen of Wei (445–396 BC). From 408–406 BC, he conquered Zhongshan to the northeast. He also pushed west across the Yellow River.

Wei's growing power made Zhao leave the alliance. In 383 BC, Zhao moved its capital to Handan and attacked the small state of Wey. Wey asked Wei for help, and Wei attacked Zhao. Zhao then called on Chu for help. Chu used this as an excuse to take land to its north. This conflict ended the power of the united Jins. It started a time of changing alliances and wars on many fronts.

In 376 BC, Han, Wei, and Zhao removed Duke Jing of Jin from power. They divided the last parts of Jin's territory among themselves. This was the final end of the Jin state.

In 370 BC, Marquess Wu of Wei died without naming a successor. This led to a war over who would rule next. After three years of civil war, Zhao and Han invaded Wei. Just as they were about to conquer Wei, the leaders of Zhao and Han disagreed. Both armies suddenly left. This allowed King Hui of Wei to become the ruler of Wei.

By the end of this period, Zhao stretched from the Shanxi plateau to the borders of Qi. Wei reached east to Qi, Lu, and Song. To the south, the weaker state of Han controlled the Yellow River valley. It surrounded the Zhou royal lands at Luoyang.

Qi's Rise to Power (379–340 BC)

Duke Kang of Qi died in 379 BC without an heir from his family. The throne went to the future King Wei, from the Tian family. The Tian family had been very powerful in Qi's government. Now, they openly took control.

The new ruler worked to get back lands that Qi had lost to other states. He won campaigns against Zhao, Wey, and Wei. This expanded Qi's territory to the Great Wall again. Historian Sima Qian wrote that other states were so impressed that no one dared attack Qi for over 20 years. Qi's military strength also brought peace to its own people during King Wei's rule.

By the end of King Wei's reign, Qi had become the strongest state. It declared its ruler a "king," showing its independence from the Zhou dynasty.

Wars of Wei

King Hui of Wei (370–319 BC) worked to make his state strong again. From 362–359 BC, he traded lands with Han and Zhao to make their borders clearer.

In 364 BC, Qin defeated Wei at the Battle of Shimen. Wei was only saved when Zhao stepped in. Qin won another victory in 362 BC. In 361 BC, Wei moved its capital east to Daliang to be safer from Qin.

In 354 BC, King Hui of Wei launched a big attack on Zhao. By 353 BC, Zhao was losing badly, and its capital, Handan, was under attack. The State of Qi stepped in to help. The famous Qi strategist, Sun Bin, suggested attacking Wei's capital while its army was busy besieging Zhao. This plan worked. The Wei army quickly moved south to protect its capital. They were caught on the road and badly defeated at the Battle of Guiling. This battle is remembered in a famous strategy called "besiege Wei, save Zhao." It means to attack a weak spot to relieve pressure somewhere else.

King Hui also supported philosophy and arts. He is known for hosting the Confucian philosopher Meng Zi at his court. Their talks are in the first two chapters of the book named after Meng Zi.

Dukes Become Kings

Qi and Wei Become Kingdoms (344 BC)

The title of "king" (wang, 王) was held by the Zhou dynasty rulers, who were mostly figureheads. Most state rulers had titles like "duke" (gong, 公) or "marquess" (hou, 侯). Chu was an exception; its rulers had been called kings since King Wu of Chu started using the title around 703 BC.

In 344 BC, the rulers of Qi and Wei recognized each other as "kings." These were King Wei of Qi and King Hui of Wei. This was a big step, as it meant they were declaring their independence from the Zhou court. Unlike rulers in the Spring and Autumn period, this new generation of rulers didn't pretend to be vassals of the Zhou dynasty. They called themselves fully independent kingdoms.

Shang Yang's Reforms in Qin (356–338 BC)

In the early Warring States period, Qin generally avoided fighting other states. This changed during the rule of Duke Xiao of Qin. His prime minister, Shang Yang, made big changes based on his Legalist ideas between 356 and 338 BC.

Shang Yang changed land ownership and rewarded farmers who produced a lot. He also encouraged people from other states to move to Qin. This increased Qin's population and weakened its rivals. He made laws for early marriage and taxes to encourage more children. He also abolished the old system where the eldest son inherited everything. He put a double tax on families with more than one son living together to break up large clans. Shang Yang also moved the capital to reduce the influence of nobles.

The Qin state became much stronger after these reforms. In 343 BC, the Zhou king recognized Qin's rise. He gave Duke Xiao the title of Count.

After the reforms, Qin became more aggressive. In 340 BC, Qin took land from Wei after Wei was defeated by Qi. In 316 BC, Qin conquered Shu and Ba in Sichuan to the southwest. Developing this area took time, but it greatly added to Qin's wealth and power.

Qin Defeats Wei (341–340 BC)

In 341 BC, Wei attacked Han. Qi waited until Han was almost defeated, then stepped in. The generals from the Battle of Guiling met again. Sun Bin and Tian Ji fought against Pang Juan. They used the same tactic: attacking Wei's capital. Sun Bin pretended to retreat, then turned on the overconfident Wei troops. He defeated them badly at the Battle of Maling. After this battle, all three Jin successor states pledged loyalty to King Xuan of Qi.

The next year, Qin attacked the weakened Wei. Wei was severely defeated and gave up a large part of its land for a truce. With Wei weakened, Qi and Qin became the most powerful states in China.

Wei started to rely on Qi for protection. King Hui of Wei met King Xuan of Qi twice. After King Hui died, his successor King Xiang also had a good relationship with Qi's king. Both promised to recognize each other as "king."

Chu Conquers Yue (334 BC)

In the early Warring States period, Chu was one of China's strongest states. It became even more powerful around 389 BC when King Dao of Chu named the famous reformer Wu Qi as his chancellor.

Chu reached its peak in 334 BC when it conquered Yue to its east. This happened when Yue was planning to attack Qi. The King of Qi sent a messenger who convinced the King of Yue to attack Chu instead. Yue launched a big attack on Chu but was defeated. Chu then went on to conquer Yue.

Qin, Han, and Yan Become Kingdoms (325–323 BC)

King Xian of Zhou tried to use his remaining power. He appointed the dukes Xian, Xiao, and Hui of Qin as leaders. This meant Qin was, in theory, the main ally of the Zhou court.

However, in 325 BC, Duke Hui of Qin felt so confident that he declared himself "king" of Qin. He used the same title as the Zhou king, effectively declaring independence. King Hui of Qin was advised by his prime minister Zhang Yi, a key figure in the School of Diplomacy.

In 323 BC, King Xuanhui of Han and King Yi of Yan also declared themselves kings. Even King Cuo of the small state of Zhongshan did the same. In 318 BC, the ruler of Song, a minor state, also called himself king. Uniquely, King Wuling of Zhao had declared himself king but took back the title in 318 BC after Zhao suffered a big defeat by Qin.

The Zhou Dynasty Splits (314 BC)

King Kao of Zhou had given his younger brother land, making him Duke Huan of Henan. Three generations later, this branch of the royal family started calling themselves "Dukes of East Zhou."

When King Nan became king in 314 BC, East Zhou became an independent state. The king lived in what became known as West Zhou.

Alliances and Conflicts (334–249 BC)

Towards the end of the Warring States period, the Qin state became much more powerful than the other six states. Because of this, the other states focused on how to deal with the Qin threat. There were two main ideas:

- 'Vertical' Alliance (hezong): This was a north-south alliance. States would team up to fight off Qin.

- 'Horizontal' Alliance (lianheng): This was an east-west alliance. A state would ally with Qin to share in its growing power.

The 'vertical' alliances had some early successes, but states often mistrusted each other, causing the alliances to break down. Qin often used the 'horizontal' alliance strategy to defeat states one by one. During this time, many thinkers and strategists traveled between states. They offered advice to rulers. These "lobbyists," like Su Qin (who liked vertical alliances) and Zhang Yi (who liked horizontal alliances), were known for their cleverness. They were called the School of Diplomacy.

Su Qin and the First Vertical Alliance (334–300 BC)

Starting in 334 BC, the diplomat Su Qin spent years visiting the courts of Yan, Zhao, Han, Wei, Qi, and Chu. He convinced them to form a united front against Qin. In 318 BC, all states except Qi launched a joint attack on Qin, but it failed.

King Hui of Qin died in 311 BC, and his prime minister Zhang Yi died a year later. The new king, King Wu, ruled for only four years before dying without a clear heir. There was some trouble in 307 BC before King Zhao became king. He was a son of King Hui by a concubine and ruled for an amazing 53 years.

After the first vertical alliance failed, Su Qin went to live in Qi. He was favored by King Xuan, which made other ministers jealous. In 300 BC, an assassination attempt left Su Qin badly wounded but not dead. Feeling he was dying, he advised the new king, King Min, to publicly execute him. This would make the assassins reveal themselves. King Min did as Su Qin asked, ending the first group of Vertical alliance thinkers.

The First Horizontal Alliance (300–287 BC)

King Min of Qi was greatly influenced by Lord Mengchang, a grandson of the former King Wei of Qi. Lord Mengchang formed a westward alliance with Wei and Han. In the far west, Qin, which had been weakened by a power struggle, joined the new group. Qin even made Lord Mengchang its chief minister. This "horizontal" or east-west alliance might have brought peace, but it left out the State of Zhao.

Around 299 BC, the ruler of Zhao became the last of the seven major states to declare himself "king."

In 298 BC, Zhao offered Qin an alliance, and Lord Mengchang was forced out of Qin. The remaining three allies, Qi, Wei, and Han, attacked Qin. They fought their way up the Yellow River to the Hangu Pass. After three years, they took the pass and forced Qin to return land to Han and Wei. They then badly defeated Yan and Chu. During Lord Mengchang's five years in power, Qi was the strongest power in China.

In 294 BC, Lord Mengchang was involved in a coup d'état and fled to Wei. His alliance system fell apart. Qi and Qin made a truce and focused on their own goals. Qi moved south against the State of Song. Meanwhile, the Qin General Bai Qi pushed eastward against a Han/Wei alliance, winning a big victory at the Battle of Yique.

In 288 BC, King Zhao of Qin and King Min of Qi took the title "Di" (帝, meaning "emperor") of the west and east, respectively. They made a promise to each other and started planning an attack on Zhao.

Su Dai and the Second Vertical Alliance

In 287 BC, the strategist Su Dai, younger brother of Su Qin, convinced King Min that the war against Zhao would only help Qin. King Min agreed and formed a 'vertical' alliance with the other states against Qin. Qin backed off, gave up the title of "Di," and returned land to Wei and Zhao. In 286 BC, Qi took over the state of Song.

The Second Horizontal Alliance and Fall of Qi

In 285 BC, Qi's success scared the other states. Led by Lord Mengchang, who was exiled in Wei, Qin, Zhao, Wei, and Yan formed an alliance. Yan was usually a weak ally of Qi, so Qi didn't expect much trouble from them. Yan's attack under general Yue Yi was a huge surprise. At the same time, the other allies attacked from the west. Chu said it was an ally of Qi but only took some land to its north. Qi's armies were destroyed, and Qi's territory was reduced to just two cities: Ju and Jimo. King Min himself was later captured and killed by his own followers.

King Xiang became king in 283 BC. His general Tian Dan was eventually able to get back much of Qi's land. However, Qi never regained the power it had under King Min.

Qin and Zhao Expand

In 278 BC, General Bai Qi of Qin attacked from Qin's new territory in Sichuan. He captured the capital of Ying, and Chu lost its western lands on the Han River. This moved Chu's main area significantly to the east.

After Chu was defeated in 278 BC, the main powers left were Qin in the west and Zhao in the north-center. There wasn't much room for diplomacy; wars decided things. Zhao had become much stronger under King Wuling of Zhao (325–299 BC). In 307 BC, he increased his cavalry by copying northern nomads. In 306 BC, he took more land in the northern Shanxi plateau. In 305 BC, he defeated the northeastern border state of Zhongshan. In 304 BC, he pushed far to the northwest. King Huiwen of Zhao (298–266 BC) chose skilled officials and expanded against the weakened Qi and Wei. In 296 BC, his general Lian Po defeated two Qin armies.

In 269 BC, Fan Sui became Qin's chief advisor. He pushed for strict reforms, constant expansion, and alliances with distant states to attack nearby ones. His idea was to "attack not only the territory, but also the people." This led to more frequent mass killings.

Qin-Zhao Wars (282–257 BC)

In 265 BC, King Zhaoxiang of Qin attacked the weak state of Han. Han controlled the Yellow River gateway into Qin. Qin moved northeast across Wei territory to cut off Han's land of Shangdang. The Han king agreed to give up Shangdang, but the local governor refused and gave it to King Xiaocheng of Zhao. Zhao sent Lian Po, who set up his armies at Changping. Qin sent general Wang He. Lian Po was too smart to risk a big battle with the Qin army and stayed inside his forts. Qin couldn't break through, and the armies were stuck for three years. The Zhao king thought Lian Po wasn't aggressive enough and sent Zhao Kuo, who promised a decisive battle. At the same time, Qin secretly replaced Wang He with the very violent Bai Qi. When Zhao Kuo left his forts, Bai Qi used a clever tactic, pulling back in the center and surrounding the Zhao army from the sides. After being surrounded for 46 days, the starving Zhao troops surrendered in September 260 BC. It is said that Bai Qi killed all the prisoners, and Zhao lost 400,000 men.

Qin was too tired to follow up its victory. Later, it sent an army to attack the Zhao capital, but the army was destroyed when it was attacked from behind. Zhao survived, but no single state could resist Qin on its own anymore. The other states could have survived if they stayed united against Qin, but they did not.

In 257 BC, the Qin army failed to besiege Handan. It was defeated by the combined forces of Zhao, Wei, and Chu during the Battle of Handan.

End of the Zhou Dynasty (256–249 BC)

The forces of King Zhao of Qin defeated King Nan of Zhou and conquered West Zhou in 256 BC. They claimed the Nine Cauldrons, which symbolically made Qin the new Son of Heaven.

King Zhao's very long rule ended in 251 BC. His son King Xiaowen, already old, died just three days after becoming king. He was followed by his son King Zhuangxiang of Qin. The new Qin king then conquered East Zhou, seven years after West Zhou fell. This brought an end to the 800-year Zhou dynasty, which was China's longest-ruling family.

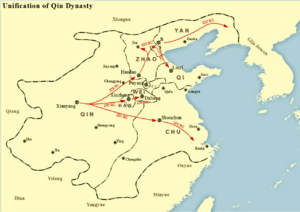

Qin Unites China (247–221 BC)

King Zhuangxiang of Qin ruled for only three years. His son Zheng became king. Unlike the two old kings before him, Zheng was only 13 years old when he took the throne. As an adult, Zheng became a brilliant commander. In just nine years, he unified all of China.

Conquest of Han

In 230 BC, Qin conquered Han. Han was the weakest of the Seven Warring States. It was next to the much stronger Qin and had been attacked by Qin many times. King An of Han, fearing that Han would be Qin's next target, quickly sent diplomats to surrender his entire kingdom without a fight. This saved the people of Han from a terrible war.

Conquest of Wei

In 225 BC, Qin conquered Wei. The Qin army directly invaded Wei. They besieged its capital Daliang, but the city walls were too strong. They came up with a new plan: they used a local river connected to the Yellow River to flood the city's walls. This caused huge damage to the city. Seeing this, King Jia of Wei quickly came out of the capital and surrendered to the Qin army. He wanted to prevent more bloodshed for his people.

Conquest of Chu

In 223 BC, Qin conquered Chu. The first invasion was a disaster. 200,000 Qin troops, led by General Li Xin, were defeated by 500,000 Chu troops. This happened in the unfamiliar territory of Huaiyang. Xiang Yan, the Chu commander, had tricked Qin by letting them win a few early battles. Then, he counterattacked and burned two large Qin camps.

In 222 BC, Wang Jian was called back to lead a second invasion with 600,000 men against Chu. The Chu forces were confident after their victory the year before. They decided to defend against what they thought would be a siege of Chu. However, Wang Jian decided to weaken Chu's determination. He tricked the Chu army by appearing to be idle in his forts. Secretly, he trained his troops to fight in Chu territory. After a year, the Chu defenders decided to break up because Qin seemed to be doing nothing. Wang Jian then invaded with full force. He overran Huaiyang and the remaining Chu forces. Chu lost its advantage and could only fight with small groups. It was fully conquered when Shouchun was destroyed and its last leader, Lord Changping, died in 223 BC. At their peak, the combined armies of Chu and Qin had hundreds of thousands to a million soldiers. This was more than those involved in the Battle of Changping between Qin and Zhao 35 years earlier.

Conquest of Zhao and Yan

In 222 BC, Qin conquered Zhao and Yan. After conquering Zhao, the Qin army turned its attention to Yan. Realizing the danger, Crown Prince Dan of Yan sent Jing Ke to try and assassinate King Zheng of Qin. This failed attempt only made the Qin king angrier and more determined. He increased his troops to conquer the Yan state.

Conquest of Qi

In 221 BC, Qin conquered Qi. Qi was the last state left to conquer. It had not helped other states when Qin was conquering them. As soon as Qin's plan to invade became clear, Qi quickly surrendered all its cities. This completed the unification of China and started the Qin dynasty. The last Qi king lived out his days in exile.

The Qin king, Ying Zheng, declared himself Qin Shi Huangdi, which means "The first Sovereign Emperor of Qin."

Under the Qin state, China was united mainly by military power. The old feudal system was ended. Noble families were forced to live in the capital city, Xianyang, so they could be watched. A national road system and more canals were built. This made it easy and fast to move and supply the army. Farmers were given more rights to land, but they had to pay taxes. This brought a lot of money to the state.

Military Changes and Ideas

Bigger Battles and New Weapons

Chariots were important in Chinese warfare for a long time. But near the beginning of the Warring States period, armies started using more foot soldiers (infantry). This might have been because the crossbow was invented. This change had two big effects. First, rulers weakened their chariot-riding nobles so they could directly control the peasants, who could be drafted as foot soldiers. This also led to a shift from noble-led governments to more organized, bureaucratic ones. Second, it made wars much bigger. When the Zhou overthrew the Shang at the Battle of Muye, they used 45,000 troops. In the Warring States period, armies were much larger:

- Qin: 1,000,000 foot soldiers, 1,000 chariots, 10,000 horses.

- Chu: Similar numbers.

- Wei: 200,000–360,000 foot soldiers, 200,000 spearmen, 100,000 servants, 600 chariots, 5,000 cavalry.

- Han: 300,000 total.

- Qi: Several hundred thousand.

For major battles, the numbers of killed soldiers were huge:

- Battle of Maling: 100,000 killed.

- Battle of Yique: 240,000 killed.

- General Bai Qi is said to have been responsible for 890,000 enemy deaths.

Many experts think these numbers are too high. But it's clear that warfare became very extreme during this time. The huge amount of fighting and suffering in the Warring States period helps explain why China has always preferred to be a united country.

Military Innovations

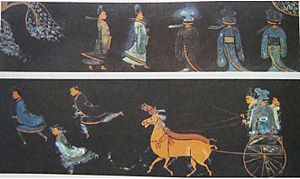

The Warring States period saw many new ideas in how to fight wars in China. For example, iron weapons and cavalry (soldiers on horseback) were introduced.

Warfare changed a lot from the Spring and Autumn period. Most armies used foot soldiers and cavalry, and chariots became less common. Using large groups of foot soldiers made battles bloodier. It also made the aristocracy (the noble class) less important, which in turn made the kings more powerful. From this period on, nobles in China became more focused on learning and government, rather than being warriors.

The states had huge armies of foot soldiers, cavalry, and chariots. Complex systems were needed to supply, train, and control these large forces. The armies ranged from tens of thousands to several hundred thousand men. Iron weapons became more common and started to replace bronze ones. Most armor and weapons from this period were made of iron.

The first official Chinese cavalry unit was formed in 307 BC. This happened during the military reforms of King Wuling of Zhao, who encouraged "nomadic dress and horse archery." But war chariots still held their importance, even though cavalry was better in some ways.

The crossbow was the main long-range weapon of this period. It could be made in large numbers easily, and many crossbowmen could be trained quickly. These qualities made it a powerful weapon against enemies.

Foot soldiers used various weapons. The most popular was the dagger-axe. These weapons came in different lengths, from 9 to 18 feet. They had a spear-like point with a slashing blade attached. Dagger-axes were very popular, especially for the Qin, who made very long, pike-like weapons.

Military Thinking

The Warring States was a great time for military strategy. Of the Seven Military Classics of China, four were written during this period:

- The Art of War: Attributed to Sun Tzu, a very important book on strategy and tactics.

- Wuzi: Attributed to Wu Qi, a leader who served the states of Wei and Chu.

- Wei Liaozi: The author is not certain.

- The Methods of the Sima: Attributed to Sima Rangju, a commander who served the state of Qi.

Culture and Society

The Warring States period was a time of constant war in ancient China. It also saw big changes in government and military systems. The major states, which ruled large areas, quickly tried to make their power stronger. This led to the final loss of respect for the Zhou court. As a sign of this change, the rulers of all major states (except Chu, which had claimed the king title much earlier) stopped using their old feudal titles. They instead used the title of 王, or King, claiming to be equal to the Zhou rulers.

At the same time, the constant fighting and the need for new ways to organize society led to many new ideas about philosophy. These are now known as the Hundred Schools of Thought. The most important ideas included:

- Mohism: Taught by Mozi, it focused on fairness and kindness.

- Confucianism: Represented by Mencius and Xunzi, it focused on moral principles.

- Legalism: Represented by Shang Yang, Shen Buhai, Shen Dao, and Han Fei, it focused on strict laws.

- Taoism: Represented by Zhuangzi and Lao Tzu, it focused on living in harmony with nature.

The many states competing with each other tried to show their power not just through their armies, but also through their courts and state philosophies. Many different rulers adopted different philosophies if they thought it would benefit them or their kingdom.

Mencius tried to make Confucianism the state philosophy. He suggested that if a state was governed by kindness and fairness, it would gain popular support from its own people and neighboring states. This would remove the need for war. Mencius tried to convince King Hui of Liang, but he was not successful. The king saw no advantage in this idea during a time of wars.

Mohism was developed by Mozi (468–376 BC). It offered a unified moral and political philosophy based on being fair and kind to everyone. Mohists believed that people change depending on their surroundings. The same applied to rulers, which is why one had to be careful of foreign influences. Mozi was very much against warfare, but he was a great tactician in defense. He defended the small state of Song from many attacks by the Chu state.

Taoism was supported by Laozi. It believed that human nature was good and could become perfect by returning to its original state. It thought that humans, like babies, are simple and innocent. But with the growth of civilizations, they lost their innocence and became greedy. Unlike other schools, Taoism did not want to gain power in state offices. Laozi even refused to be a minister for the state of Chu.

Legalism, created by Shang Yang in 338 BC, rejected all ideas of religion and old practices. It believed a nation should be ruled by strict laws. Not only were severe punishments given, but families were also held responsible for crimes. It suggested big changes and created a society based on clear ranks. Farmers were encouraged to farm, and military success was rewarded. Laws applied to everyone, with no exceptions; even the king was not above punishment. The Qin state adopted this philosophy. It helped Qin become a well-organized, centralized state with government officials chosen based on their skills.

This period is most famous for creating complex governments and centralized power. It also established clear legal systems. These developments in how politics and military were organized were the basis of the Qin state's power. Qin conquered the other states and united them under the Qin Empire in 221 BC.

Nobles, Officials, and Reformers

The intense warfare, which used large groups of foot soldiers instead of just chariots, was a major reason for the creation of strong central governments in each state. At the same time, the process where land was divided among nobles, which led to events like the splitting of Jin, was eventually reversed by this new system of government.

Because of the demands of warfare, states adopted new government systems during the Warring States period. Wei adopted these in 445 BC, Zhao in 403 BC, Chu in 390 BC, Han in 355 BC, Qi in 357 BC, and Qin in 350 BC. Power became centralized by limiting the power of land-owning nobles and creating a new system based on good service to the state. Officials were chosen from lower levels of society. Systems for checking accounts and reporting, and fixed salaries for officials were created.

The reforms by Shang Yang in Qin and Wu Qi in Chu both focused on making the central government stronger. They reduced the power of the nobility and greatly increased the government's role based on Legalist ideas. These changes were necessary to gather the large armies needed during this period.

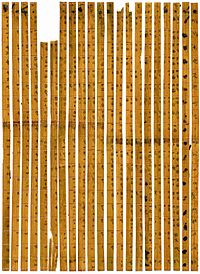

Advanced Math

A group of 21 bamboo slips from the Tsinghua collection, dated to 305 BC, show the world's earliest example of a two-digit decimal multiplication table. This means that advanced math for business was already being used during this period.

Rod numerals were used to show both negative and positive whole numbers, and fractions. This was a true place-value number system, with a blank space for zero, going back to the Warring States period.

Literature of the Period

An important book from the Warring States period is the Zuo Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals. This book summarizes the earlier Spring and Autumn period. A less famous work, Guoyu, is thought to be by the same author.

Many sayings of philosophers from the Spring and Autumn period, which had been passed down orally, were written down during the Warring States period. These include the Analects and The Art of War.

Economic Developments

The Warring States period saw a lot of iron working in China. Iron replaced bronze as the main metal used in warfare. Areas like Shu (today's Sichuan) and Yue (today's Zhejiang) also became part of Chinese culture during this time. Trade also became important, and some merchants had a lot of power in politics. The most famous was Lü Buwei, who became Chancellor of Qin and was a key supporter of the future Qin Shihuang.

At the same time, the stronger, more organized states had more resources. They also needed to support large armies and big wars. This led to many economic projects, like large water systems. Important examples include the Dujiangyan Irrigation System, which controlled the Min River in Sichuan. This turned a less developed region into a major supply base for Qin. Another was the Zhengguo Canal, which watered large areas of land in the Guanzhong Plain, further increasing Qin's farm output.

The Guanzi is considered one of the most important texts about the developing economy in the Warring States period. It talks about how to control prices for goods. It explains how to understand if a product is "light" (unimportant, not essential, or cheap) or "heavy" (important, essential, or expensive). It also explains that whether a product is "light" or "heavy" depends on the situation and other products.

See also

In Spanish: Reinos combatientes para niños

In Spanish: Reinos combatientes para niños

- Feudalism

- Sengoku period – A period in Japanese history named after this period

- Three Kingdoms

- Warlord Era