King Zhou of Shang facts for kids

Quick facts for kids King Di Xin of Shang |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

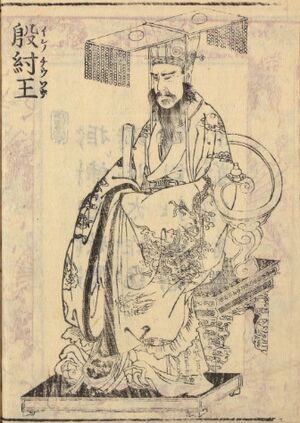

King Zhou of Shang illustrated in the Ehon Sangoku Yōfuden (c. 1805)

|

|||||||||

| King of Shang dynasty | |||||||||

| Reign | 1075–1046 BCE (29 years) | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Di Yi (his father) | ||||||||

| Born | 1105 BCE | ||||||||

| Died | 1046 BCE | ||||||||

| Spouse | Consort Daji Jiuhou Nü |

||||||||

| Issue | Wu Geng | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Father | Di Yi | ||||||||

King Zhou ([ʈ͡ʂoʊ]) was the last king of the Shang dynasty in ancient China. His real name was Di Xin of Shang (Chinese: 商帝辛; pinyin: Shāng Dì Xīn) or King Shou of Shang (Chinese: 商王受; pinyin: Shāng Wáng Shòu). The name "Zhou" (Chinese: 紂; pinyin: Zhòu) was actually a negative nickname given to him after his death. It means something like a "horse crupper," which is the part of a saddle that gets dirty. This name was used to show that people thought he was a bad ruler.

His story later became a cautionary tale. This means it was a warning about what can happen to a kingdom if its leader becomes corrupt and acts badly.

King Zhou: A Story from Ancient China

What's in a Name?

Di Xin was born with the family name Zi and the given name Shou. During his life, people often called him King Shou of Shang. After he died, the new Zhou dynasty gave him the negative name King Zhou of Shang (商紂王). The word "Zhou" (紂) was chosen to mean "injustice and harm." It's important not to confuse this "Zhou" with the name of the new Zhou dynasty, which is spelled and pronounced differently (Chinese: 周; pinyin: Zhōu).

His Early Years as King

In old writings like the Records of the Grand Historian, it's said that Di Xin was very smart and strong when he first became king. He was quick-witted and could win any argument. Legends even say he was strong enough to hunt wild animals with his bare hands.

He was the son of King Di Yi. Di Xin also expanded the Shang territory. He fought against tribes around his kingdom, including the Dongyi people to the east.

Challenges in His Later Reign

As King Zhou got older, he started to ignore many important government matters. To pay for the kingdom's large daily costs, he made people pay very high taxes. This caused a lot of suffering among the people. They began to lose hope in the Shang dynasty.

His relatives tried to advise him. His brother Wei Zi tried to convince him to change his ways. However, King Zhou refused to listen. His uncle Bi Gan also spoke to him about his actions. Sadly, King Zhou was very cruel to those who disagreed with him. Another uncle, Ji Zi, pretended to be sick to avoid the king's anger.

The End of His Rule

Eventually, the Zhou dynasty army, led by Jiang Ziya, fought against the Shang dynasty. This big battle, called the Battle of Muye, happened in 1046 BC. The Shang army was defeated.

After the defeat, King Di Xin went to his palace. He gathered all his valuable treasures around him. Then, he set his palace on fire and ended his own life. The name "Zhou" (紂) became widely used after his death. It was meant to show how bad his rule had become. Over many centuries, he became known as a truly wicked ruler.

King Zhou in Stories and Legends

King Zhou is mentioned in important Chinese texts like the Confucian Analects. He is also a main character in a famous story called Fengshen Yanyi (which means Investiture of the Gods). This story and others like it are very popular.

Because of these stories, King Zhou is often used as a bad example. He shows what happens when a ruler is not good. This helped explain the idea of the Mandate of Heaven. This idea says that a ruler's right to rule comes from heaven. If a ruler is bad, heaven will allow a new dynasty to take over.

History vs. Legend: What Do We Really Know?

Many historians today believe that some stories about King Di Xin were made up or exaggerated. These stories were written long after he died. Modern historians think he might have been more reasonable and intelligent than the legends say. They believe many of the cruel acts linked to him might not be true.

Archaeologists have found evidence that helps us understand the Shang dynasty better. For example, Tomb 1567 at the Yinxu site was likely built for King Zhou. However, he was not buried there because of how he died in battle.

After the Shang dynasty fell, King Di Xin and Jie of Xia (the last king of the Xia dynasty) were often described as tyrants. But some ancient and modern historians have questioned these stories. They found that archaeological discoveries sometimes don't match the old records. Also, older records about Di Xin are less harsh than newer ones.

Changing Burial Customs

Archaeological digs show that toward the end of the Shang dynasty, burials changed. More metal and wood items were buried with people. There were fewer human or animal sacrifices for rituals. This suggests a move towards simpler burial customs. Before Di Xin, King Zu Jia also simplified rituals. He used more grain and dance instead of sacrifices. This was a progressive change. However, the later Zhou dynasty saw it as disrespectful to ancestors.

Women's Roles in Shang Society

During the Shang dynasty, women had many important jobs. They managed rituals, advised on military matters, and handled court guests. Scholars believe women had a much higher status in the Shang dynasty than in the later Zhou dynasty. The Zhou dynasty, influenced by Confucian ideas, focused more on women's roles at home, like making silk. The Shang dynasty's practice of women in power shows a more equal culture for its time.

The "Mandate of Heaven" Idea

The idea of the "Mandate of Heaven" is quite complex. Some scholars believe the Shang dynasty didn't have the same idea of it as later dynasties. For them, "Mandate of Heaven" might have meant "the command of the ancestors." This was about the spiritual power of ancestors to bless or abandon someone's life.

How History Changes Over Time

Historians have noticed that the stories about King Di Xin became more detailed and negative over time. During the Spring and Autumn period, thinkers traveled around China. They used King Di Xin as a bad example in their stories. They wanted to show that "evil deserves punishment." These stories added many new accusations to King Zhou.

Later dynasties, especially the Han dynasty, continued to spread this negative image. Over hundreds of years, King Di Xin became known as the ultimate tyrant. This makes it hard to tell what is true history and what is just a legend.