Heian-kyō facts for kids

Heian-kyō (pronounced Hey-ahn-kyo) was an old name for the city we now call Kyoto. It was the official capital of Japan for over 1,000 years. This long period lasted from 794 to 1868. There was only a short break in 1180.

Emperor Kanmu made it the capital in 794. He moved the Imperial Court (the emperor's government) from nearby Nagaoka-kyō. His advisor, Wake no Kiyomaro, suggested the move. This event started the important Heian period in Japanese history. Experts believe the city's design was like Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an), the capital of China's Tang dynasty.

Heian-kyō was the main political center until 1185. That's when the samurai Minamoto family beat the Taira family in the Genpei War. After this, the samurai moved the government to Kamakura. They set up the Kamakura shogunate, a military government.

Even though samurai leaders (called shoguns) held the real power, Heian-kyō stayed important. It was still where the Imperial Court was located. This meant it was still the official capital of Japan.

Contents

What Heian-kyō Looked Like

Heian-kyō was built in the middle of what is now Kyoto city. It was a large rectangle, about 4.5 kilometers (2.8 miles) wide and 5.2 kilometers (3.2 miles) long. The city's design was similar to Heijō-kyō, an earlier Japanese capital.

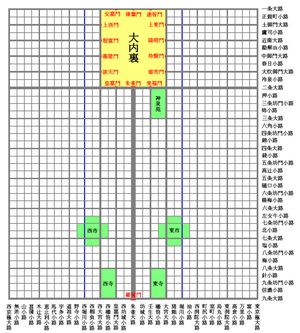

The Daidairi (the Imperial palace) was in the very center of the northern part of the city. A wide main road called Suzaku Avenue (Suzaku-ōji) ran straight from the palace. It went all the way through the city's center. This road split the city into two parts: the Right Capital (Ukyō) and the Left Capital (Sakyō). The emperor would look south from the palace. So, the eastern side was called the Left Capital, and the western side was the Right Capital.

The city's design was like the Chinese capital of Chang'an. But Heian-kyō was different because it had no city walls. People think the city's spot was chosen using Feng shui ideas. This is an ancient Chinese practice about how to arrange things to bring good luck. It was based on the "Four Gods Suitability" ([[Nihongo|Shijinsōō|ja:四神相応]]) principle.

The original Heian-kyō was smaller than modern Kyoto. For example, its northern edge, Ichijō-ōji, is now near present-day Imadegawa-dōri. The southern edge, Kyūjō-ōji, is now just south of JR Kyōto Station.

City Layout and Streets

Heian-kyō was planned as a perfect square city. The basic unit of measurement was a jō, which was about 3.03 meters (10 feet). Forty square jō made a chō, which was a block about 121.2 meters (398 feet) on each side.

The city had major streets called ōji and smaller streets called koji. The city was divided into sections. Four rows of chō running east to west made a jō (a different jō from the measurement unit). Four rows of chō running north to south made a bō. Each chō within a jō and bō was given a number from 1 to 16. This system made it easy to find addresses, like "Right Capital, Jō Five, Bō Two, Chō Fourteen."

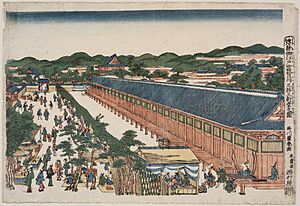

Even the small streets were wide, about 12 meters (39 feet) across. The major streets were even wider, over 24 meters (79 feet). Today, most streets in Kyoto are much narrower. For example, Suzaku-ōji was a huge 84 meters (276 feet) wide! Also, two artificial rivers, Horikawa and Nishi Horikawa, ran alongside some streets.

Heian-kyō's History

In 784 AD, Emperor Kanmu built Nagaoka-kyō as the new capital. He moved it from Heijō-kyō. He probably wanted a new capital far from powerful temples and nobles. But just nine years later, in 793 AD, Emperor Kanmu decided to move the capital again.

The new location was Kadono, between two rivers in northern Yamashiro. It was about ten kilometers (6.2 miles) northeast of Nagaoka-kyō. It's said that Emperor Kanmu had seen Kadono from a high point and thought it was perfect. He said, "Kadono has beautiful mountains and rivers. It also has good transport by sea and land. This makes it easy for people to gather there from all over the country."

Building the Capital

Building Heian-kyō likely started with the palace. Then, the rest of the city was built. The Daigokuden, the main palace building, was placed at the very north of the main road, Suzaku-ōji. This showed the emperor's power, as the building could be seen from anywhere in the city.

Ports like Yodonotsu and Ōitsu were set up along the river near the city. These ports helped bring goods from all over Japan into the city. The goods then reached people through two big markets: the East Market and the West Market. This steady supply of food and goods helped the city's population grow.

The city also had ways to prevent flooding, which had been a problem in Nagaoka-kyō. Even though there was no natural river in the city center, two artificial canals (today's Horikawa and Nishi Horikawa) were dug. Their water levels could be controlled. This provided water and also protected against floods.

Like the previous capital, building new Buddhist temples was mostly forbidden in Heian-kyō. Only the East and West temples were allowed. People believed these temples would protect the city from disasters and sickness. Important priests like Kūkai were welcomed. They were wise men who knew a lot about Buddhist teachings and were not interested in political power.

On October 22, 794 AD, Emperor Kanmu arrived at the new city. On November 8, he announced, "I hereby name this city Heian-kyō." He also changed the second Japanese character for Yamashiro. He changed it from "back" to "castle." This was because the capital looked like a natural "mountain castle" surrounded by mountains to the east, north, and west.

Changes Over Time

In 810 AD, some people wanted to move the capital back to Heijō-kyō. This happened during a disagreement about who would be the next emperor. But Emperor Saga believed keeping the capital in Heian-kyō was best for the country's stability. He called Heian-kyō "The Eternal City" (Yorozuyo no Miya).

The western part of the city (the Right Capital) was built on wetlands near the Katsura River. It was hard to develop this area. By the 10th century, much of it was run-down. It even started to be used for farming, which was not allowed inside the city. Most rich families, like the Fujiwara clan, lived in the northern part of the Left Capital.

Poorer people started living by the Kamo River, outside the city's eastern edge. Temples and country homes also appeared on the river's eastern banks. This began a trend of the city growing towards the east. In 980 AD, the Rajōmon, the grandest of the two city gates, fell down and was never rebuilt. This meant the city's original boundaries started to expand eastward. This is how the streets of medieval and modern Kyoto began to form.

When the Kamakura and Edo shogunates (military governments) took power, Heian-kyō became less important as a center of power. The city suffered greatly during the Muromachi and Sengoku periods. Almost half the city was burned down during the Ōnin war. After this, Heian-kyō split into two smaller cities, upper (Kamigyō) and lower (Shimogyō).

However, the two parts were reunited during the Azuchi–Momoyama period when Oda Nobunaga rose to power. During the Meiji Revolution, Edo was renamed Tokyo and became the new capital of Japan. Heian-kyō lost its status as the main capital. But it became a "backup" capital for when the emperor was away in Tokyo. The emperor has not returned to Kyoto since then. Still, Emperor Meiji made sure the imperial residences were kept safe. The takamikura, a special throne that marks the emperor's seat, is still at the palace in Kyoto.

Heian-kyō City Plan

The green parts in the diagram show markets, temples, and a garden. There were two big markets, West Market and East Market. They were located on the seventh street, Shichijō-ōji. Tō-ji ("East Temple") and Sai-ji ("West Temple") were Buddhist temples built at the southern edge of the capital. An imperial garden called Shinsenen was next to the Daidairi (main palace).

In English (major streets and palace only):

- Note: "七条大路" is listed twice by mistake in the diagram.

Palace Gates

The gates of the Daidairi (main palace) are listed below. The Japanese names are given with their English spellings.

| Side (direction) |

Gate name | Street name |

|---|---|---|

| South side (east to west) |

Bifuku-mon 美福門 | Mibu |

| Suzaku-mon 朱雀門 | Suzaku-ōji | |

| Kōga-mon 皇嘉門 | Kōgamon-ōji | |

| West side (south to north) |

Datten-mon 談天門 | Ōimikado |

| Sōheki-mon 藻壁門 | Nakamikado | |

| Impu-mon 殷富門 | Konoe | |

| Jōsai-mon 上西門 | Tsuchimikado | |

| North side (west to east) |

Anka-mon 安嘉門 | |

| Ikan-mon 偉鑒門 | ||

| Tachi-mon 達智門 | ||

| East side (north to south) |

Jōtō-mon 上東門 | Tsuchimikado |

| Yōmei-mon 陽明門 | Konoe | |

| Taiken-mon 待賢門 | Nakamikado | |

| Ikuhō-mon 郁芳門 | Ōimikado |

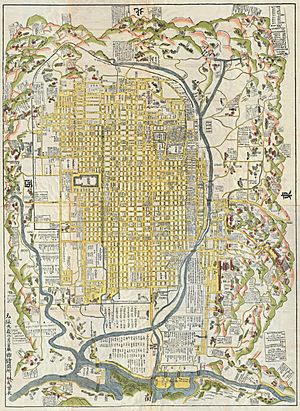

Old Map of Kyoto

Below is a map of Kyoto from 1696. It is known as the Genroku 9 Kyoto Daizu (元禄九年京都大絵図). This map is kept at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

See also

In Spanish: Heian-kyō para niños

In Spanish: Heian-kyō para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |