Kūkai facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kūkai |

|

|---|---|

| 空海 | |

Painting of Kūkai from the Shingon Hassozō, a set of scrolls depicting the first eight patriarchs of the Shingon school. Japan, Kamakura period (13th-14th centuries).

|

|

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Vajrayana Buddhism, Shingon |

| Personal | |

| Born | 27 July 774 (15th day, 6th month, Hōki 5) Zentsūji, Sanuki Province, Japan |

| Died | 22 April 835 (age 60) (21st day, 3rd month, Jōwa 2) Mount Kōya, Japan |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | Founder of Shingon Buddhism |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Huiguo |

Kūkai (空海; 27 July 774 – 22 April 835) was a famous Japanese Buddhist monk. He was born as Saeki no Mao. After his death, he was given the special name Kōbō Daishi, which means "The Grand Master who Spread the Teachings".

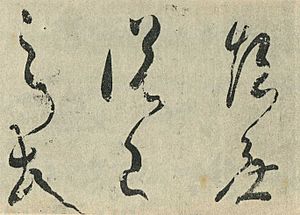

Kūkai was not just a monk; he was also a talented calligrapher (someone who writes beautifully) and a poet. He founded a special type of Buddhism in Japan called Shingon Buddhism. This school is part of a larger branch of Buddhism known as Vajrayana, which focuses on secret teachings and rituals.

To learn more about Buddhism, Kūkai traveled to China. There, he studied a type of Chinese Buddhism called Tangmi under a wise monk named Huiguo. When he returned to Japan, he started the Shingon school.

With support from several Emperors, Kūkai was able to share his Shingon teachings. He also helped build many Shingon temples. Like other important monks, Kūkai also worked on public projects, such as building dams. He chose Mount Kōya as a sacred place and lived there until he passed away in 835 CE.

Because Kūkai was so important in Japanese Buddhism, many stories and legends are told about him. Some people even say he invented the kana writing system. This system is still used today to write the Japanese language, along with kanji characters. He is also linked to the Iroha poem, which helped make kana popular.

Followers of Shingon Buddhism often call Kūkai by the respectful title Odaishi-sama, meaning "The Grand Master". His religious name is Henjō Kongō, which means "Vajra Shining in All Directions".

Contents

Kūkai's Life Story

Early Years and Studies

Kūkai was born in 774 in a place called Zentsū-ji temple, on the island of Shikoku. His family, the Saeki family, was part of the nobility. His birth name is thought to be Mao, meaning "True Fish".

Kūkai grew up during a time of big changes in Japan. The emperor was trying to make his power stronger. When Kūkai was 15, he began studying classic Chinese writings with his uncle.

Later, around 791, Kūkai went to Nara, which was the capital city. He studied at the government university there. People who graduated from this university usually got important jobs in the government.

However, Kūkai became more interested in Buddhist studies than in his other subjects, like Confucianism. When he was about 22, he started practicing Buddhism. He often went to quiet mountain areas to chant special prayers called mantras.

At 24, Kūkai wrote his first big book, Sangō Shiiki. In this book, he used ideas from Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. He found these texts in the large libraries of the Nara temples.

During this time, the government controlled Buddhism very strictly. Monks who practiced on their own, like Kūkai, were often not allowed. They had to travel from place to place.

Kūkai had a dream where a man told him about a special Buddhist book. This book was called the Mahavairocana Tantra. Kūkai found a copy of it in Japan, but it was hard to understand. Parts of it were in Sanskrit, an ancient Indian language, written in a script called Siddhaṃ.

Since no one in Japan could explain the book to him, Kūkai decided to go to China. He wanted to study the text there and learn its secrets.

Journey to China

In 804, Kūkai joined a trip to China that was supported by the government. He wanted to learn more about the Mahavairocana Tantra. It's not clear why Kūkai, a monk not officially sponsored by the state, was chosen for this important mission.

The trip involved four ships. Kūkai was on the first ship, and another famous monk named Saichō was on the second. During a storm, one ship turned back, and another was lost at sea. Kūkai's ship arrived weeks later in China.

They were first stopped from entering the port. Kūkai, who spoke Chinese well, wrote a letter to the governor. He explained their situation, and they were allowed to dock. The group then traveled to Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an), the capital of the Tang Dynasty.

In Chang'an, Kūkai began studying Chinese Buddhism. He also learned Sanskrit from an Indian scholar.

In 805, Kūkai finally met the monk Huiguo. Huiguo was a very important Buddhist master. He was known for translating Sanskrit texts into Chinese, including the Mahavairocana Tantra. Huiguo taught Kūkai about Chinese Esoteric Buddhism.

Kūkai had planned to study in China for 20 years. But in just a few months, Huiguo taught him everything. Huiguo said teaching Kūkai was like "pouring water from one vase into another," meaning Kūkai learned very quickly. Huiguo soon passed away. But before he died, he told Kūkai to go back to Japan and share these special teachings.

Kūkai returned to Japan in 806. He was now known as the eighth master of Esoteric Buddhism. He had learned Sanskrit and the Siddhaṃ script. He also studied Indian Buddhism, Chinese calligraphy, and poetry. He brought many new Buddhist texts to Japan, especially those about esoteric teachings.

When Kūkai returned, the emperor had changed. The new emperor was not very interested in Buddhism. Another monk, Saichō, was more popular at court. Saichō had already introduced some esoteric rituals to the court.

In 812, Saichō asked Kūkai to teach him. Kūkai agreed to give him some initiations. But Kūkai refused to give Saichō the final initiation because Saichō had not completed all the necessary studies. This caused a disagreement between the two monks.

Kūkai's activities are not well known until 809. That year, the court finally responded to his report about his studies. He had also sent a list of all the texts and items he brought from China. He asked for government support to start his new Buddhist school in Japan.

The court told Kūkai to live at Takao-san temple (now Jingo-ji) near Kyoto. This temple became his main base for the next 14 years. In 809, Emperor Heizei retired, and Emperor Saga became the new ruler. Emperor Saga supported Kūkai and they exchanged poems and gifts.

Becoming Well-Known

In 810, Kūkai became a public figure. He was put in charge of Tōdai-ji, a main temple in Nara. He also became a leader in the Office of Priestly Affairs.

Soon after, Emperor Saga became very ill. Kūkai asked the Emperor if he could perform special rituals. These rituals were said to help the king, keep the seasons in harmony, and protect the country. The Emperor agreed. Before this, the government usually relied on traditional monks for such rituals. But this event showed a new trust in Kūkai's esoteric practices.

In 812, Kūkai held public initiation ceremonies at Takao-san temple. This made him the recognized master of esoteric Buddhism in Japan. He started organizing his students, giving them jobs like managing the temple and keeping discipline.

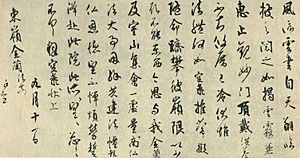

In 813, Kūkai wrote a document called The Admonishments of Konin. It explained his goals and practices. During his time at Takaosan, he also wrote many important books for the Shingon School, such as:

- Attaining Enlightenment in This Very Existence

- The Meaning of Sound, Word, Reality

- Meanings of the Word Hūm

These were all written in 817. Kūkai was also busy writing poems and performing rituals. His popularity grew, even reaching the royal court.

Kūkai's new teachings caught the attention of a scholar-monk named Tokuitsu. They exchanged letters in 815, with Tokuitsu asking for explanations. This discussion helped Kūkai gain more respect. It also made other Buddhist schools in Nara more interested in esoteric practices.

Building Mount Kōya

In 816, Emperor Saga allowed Kūkai to build a mountain retreat at Mount Kōya. Kūkai wanted a quiet place away from worldly matters. The site was officially blessed in 819 with a seven-day ceremony. Kūkai couldn't stay there long because he had to advise the government. So, he put a senior student in charge of the project.

Raising money for Mount Kōya was a big challenge for Kūkai. The project faced financial problems and was not fully finished until after Kūkai's death in 835.

Kūkai imagined Mount Kōya as a representation of the Mandala of the Two Realms. These mandalas are important symbols in Shingon Buddhism. He saw the central plateau as the Womb Realm mandala, with the surrounding peaks like lotus petals. In the middle, he planned to build the Diamond Realm mandala, a temple he named Kongōbu-ji. Inside this temple, there would be a huge statue of Vairocana, who represents ultimate reality.

Public Works and Tō-ji Temple

In 821, Kūkai took on a big civil engineering job. He helped restore the Manno Reservoir, which is still Japan's largest irrigation reservoir. His leadership helped finish the project smoothly. This event is now part of the many legends about him.

In 823, the retiring Emperor Saga asked Kūkai to take over Tō-ji (Eastern Temple). This temple, along with Sai-ji (Western Temple), was meant to protect the capital city. But after nearly 30 years, they were still not finished. Kūkai, with his experience in public works, was given full control.

Kūkai made Tō-ji the first center for Esoteric Buddhism in Kyoto. This also gave him a base closer to the court and its power. The new emperor, Emperor Junna, also supported Kūkai.

In 824, Kūkai was officially put in charge of the temple construction. He also founded Zenpuku-ji, one of the oldest temples in the Tokyo area. That same year, he was appointed to a high position in the Office of Priestly Affairs.

At Tō-ji, Kūkai added a lecture hall in 825. It was designed according to Shingon Buddhist ideas and included 14 Buddha statues. In 825, Kūkai was also asked to teach the crown prince. In 826, he started building a large pagoda at Tō-ji. It was not finished during his lifetime.

In 827, Kūkai was promoted to a very high position. He oversaw state rituals for the emperor and the imperial family.

In 828, Kūkai opened his School of Arts and Sciences. This was a private school open to everyone, no matter their social class. This was different from other schools, which were only for noble families. His school taught Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. It also provided free meals, which was important for poor students. The school closed ten years after Kūkai's death.

Final Years and Legacy

Kūkai finished his most important work, The Ten Stages of the Development of Mind, in 830. Because it was very long, he wrote a shorter summary called The Precious Key to the Secret Treasury.

In 831, Kūkai began to get sick. He wanted to retire, but the emperor would not let him. Instead, the emperor gave him sick leave. By the end of 832, Kūkai returned to Mount Kōya and spent most of his remaining life there.

In 834, he asked the court to set up a Shingon chapel in the palace. This chapel would perform rituals to ensure the health of the state. The request was granted, and Shingon rituals became part of the official court events.

In 835, just two months before he died, Kūkai was finally allowed to ordain three new Shingon monks each year at Mount Kōya. This meant that Mount Kōya, which started as a private place, was now supported by the state.

As his end approached, Kūkai stopped eating and drinking. He spent much of his time in deep meditation. He passed away at midnight on April 22, 835, at the age of 60.

Kūkai was not cremated as was traditional. Instead, following his wishes, he was buried on the eastern peak of Mount Kōya. A legend says that when his tomb was opened later, Kōbō-Daishi looked as if he was still sleeping, with his skin unchanged and hair a bit longer.

Many people believe that Kūkai did not truly die. They say he entered an eternal meditative trance (samadhi) and is still alive on Mount Kōya. He is said to be waiting for the arrival of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future.

Stories and Legends

Because Kūkai was so important, many interesting stories and legends grew around him.

One legend says that when Kūkai was looking for a place to build a temple on Mount Kōya, two Shinto gods of the mountain welcomed him. These gods were Kariba (a male hunter) and Niu (a female). Kariba supposedly guided Kūkai through the mountains with the help of a white dog and a black dog. Later, people believed that Kariba and Niu were actually forms of the Buddha Vairocana, who is central to Shingon Buddhism.

Another story is about Emon Saburō, the richest man on Shikoku island. One day, a traveling monk came to his house asking for food. Emon refused, broke the monk's begging bowl, and chased him away. After this, all eight of Emon's sons became sick and died.

Emon realized that the monk was Kūkai and felt very sorry. He decided to travel around the island many times to find Kūkai and ask for forgiveness. Finally, he collapsed, dying. Kūkai appeared and forgave him. Emon asked to be reborn into a wealthy family in Matsuyama so he could rebuild a neglected temple. He died holding a stone.

Soon after, a baby was born with his hand tightly closed around a stone. The stone had "Emon Saburō is reborn" written on it. When the baby grew up, he used his wealth to restore the temple. This temple is now called Ishite-ji, meaning "Stone-hand Temple".

Images for kids

-

Statue of Kūkai in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles

See also

In Spanish: Kūkai para niños

In Spanish: Kūkai para niños

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Kūkai. |

- Ākāśagarbha

- Huiguo

- Padmasambhava

- Shingon Buddhism

- Shikoku Pilgrimage

- Vajrayana

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |