Shingon Buddhism facts for kids

|

Basic terms |

|

|

People |

|

|

Schools |

|

|

Practices |

|

|

study Dharma |

|

Shingon (真言宗, Shingon-shū, "True Word/Mantra School") is a major school of Buddhism in Japan. It is one of the few types of Vajrayana Buddhism still practiced in East Asian Buddhism. This form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism is sometimes called "Tōmitsu," meaning "Esoteric [Buddhism] of Tō-ji." The word shingon comes from a Chinese word that means "true word" or "mantra."

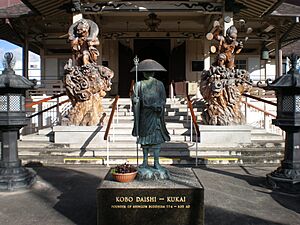

The Zhēnyán lineage started in China around the 7th and 8th centuries. It was founded by Indian masters like Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra. These special teachings later became very popular in Japan thanks to a Buddhist monk named Kūkai (空海, 774–835). Kūkai traveled to Tang China and learned these secret teachings from a Chinese master named Huiguo (746–805). Kūkai set up his tradition at Mount Kōya in Wakayama Prefecture. This mountain is still the main pilgrimage site for Shingon Buddhism.

The Shingon school teaches that you can become a Buddha "in this very body" (即身成佛 sokushin jōbutsu). This happens through special practices, especially those using the "three mysteries" (三密 sanmitsu). These mysteries involve mudras (hand gestures), mantras (sacred sounds), and mandalas (sacred diagrams). Another important idea from Shingon is that all beings are already enlightened from the start (本覺 hongaku).

Shingon's teachings and rituals influenced other Japanese traditions. These include the Tendai school, Shugendo, and Shinto. Shingon also shaped the rituals of Japanese Zen, including Soto Zen through the monk Keizan. Beyond religion, Shingon Buddhism also affected wider Japanese culture. This includes medieval Japanese art, beauty, and craftsmanship.

Contents

How Shingon Buddhism Began

Shingon Buddhism started during the Heian period (794–1185). It was founded by a Japanese Buddhist monk named Kūkai (774–835 CE). In 804, Kūkai traveled to China to study Esoteric Buddhist practices. He went to the city of Xi'an (西安), then called Chang-an. There, he studied at Qinglong Temple (青龍寺) under Huiguo. Huiguo was a student of the Indian master Amoghavajra. Kūkai returned to Japan with the teachings and scriptures of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism. These ideas quickly became popular with Japan's leaders. Over time, they grew into an organized tradition within Japanese Buddhism. Shingon followers often call Kūkai Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師, Great Master of the Propagation of Dharma). This was a special name given to him after his death by Emperor Daigo.

Kūkai's Journey to China

Kūkai was born into a noble family in Shikoku. He received a traditional Confucian education in Kyoto's college. In his 20s, he became a Buddhist. He was inspired to practice asceticism, which means living a simple life and meditating in the mountains. He also traveled the countryside as a hermit, though he visited cities to study texts. During this time, his main meditation was a mantra of the bodhisattva Ākāśagarbha. While meditating in the mountains, he had a vision of the bodhisattva flying towards him.

In this early period, Kūkai studied and prayed intensely. He searched for the deepest truth in Buddhism. One day, he dreamed of a man who told him to find the Mahāvairocana Sūtra. He found a copy in Chinese and Sanskrit. However, large parts of the text were hard for him to understand. So, he decided to go to China to find someone who could explain it.

In 804, Kūkai sailed to China with a fleet of four ships. Saichō, who would later found the Tendai school, was on the same fleet. Kūkai met Huiguo in May 805. Huiguo was sixty years old and very ill. Huiguo told Kūkai that he had been waiting for him. He immediately began teaching Kūkai about the esoteric mandalas. In just three months, Huiguo taught Kūkai everything he knew about esoteric Buddhist ideas and practices. During this time, Kūkai also learned Sanskrit from some Indian masters living in China.

Kūkai Returns to Japan

Kūkai returned to Japan in 806 after Huiguo's death. He brought back many Buddhist texts, mandalas, ritual items, and other books. After returning, Kūkai asked the emperor for permission to start a new Buddhist school. He waited three years for a reply in Kyushu. In 809, Kūkai was allowed to live at a temple near Kyoto called Takaosanji (now Jingo-ji). This temple became his main base near the capital city. Kūkai's influence grew steadily when Emperor Saga supported him. Kūkai was appointed head of Todai-ji in 810. At this time, Kūkai began giving esoteric initiations (abhiśeka). He initiated important laypeople, and even Saicho and his students. He also started organizing a new school of esoteric Buddhism around Jingo-ji. He wrote important books that explained the main teachings of Shingon.

In 818, Kūkai asked Emperor Saga to give him Mount Kōya (高野山 Kōyasan). This mountain is in what is now Wakayama province. Kūkai wanted to build a true monastic center away from the busy capital. His request was soon granted. Kūkai and his students began building the new monastery. They designed it based on the two mandalas, the womb and vajra. This mountain center quickly became the main place for Shingon study and practice. In his later life, Kūkai continued to promote Shingon rituals among the elite. He also worked to make Kōyasan a major center. Kūkai eventually gained control of Tō-ji for the Shingon school. This was a very important temple in the capital. His last request before his death in 832 was to build a Shingon hall in the Imperial palace grounds. This was for a seven-day ritual of chanting the Sutra of Golden Light. His request was granted a year after his death.

Shingon After Kūkai

After Kūkai, his main students like Jitsue, Shinzen, Shinzai, Eon, and Shōhō took over the Shingon temples. The main leader after Kūkai's death was Shinnen (804–891). Even then, there was some disagreement between Tō-ji and Kōyasan. Some Shingon monks also followed Kūkai's path and visited China to get more teachings and texts. Similarly, several Tendai monks also went to China and brought back esoteric teachings. This made Tendai esotericism a big competitor to Shingon.

Under Kangen (853–925), Tō-ji temple became the main temple of Shingon. Mount Kōya then went through a period of decline. It recovered in the 11th century with support from Fujiwara clan nobles like Fujiwara no Michinaga.

Shingon Buddhism was very popular during the Heian period (平安時代). It was especially liked by the nobility. It greatly contributed to the art and literature of that time. It also influenced other groups like the Tendai school.

During the late Heian period, Pure Land Buddhism became very popular. Shingon was also influenced by this trend. Mount Kōya soon became a center for wandering holy men called Kōya Hijiri. These groups combined Pure Land practices, which focused on Amida Buddha, with devotion to Kūkai. They also helped raise money to rebuild many temples. Kōya-san soon became a major pilgrimage site for all Japanese people.

The Shingon monk Kakuban (1095–1143) was a scholar who responded to the rise of Pure Land devotion. He studied Shingon and Tendai. He also added Pure Land practice into his Shingon system. He promoted a deeper, esoteric meaning of nembutsu and Pure Land. Unlike other Pure Land schools, Kakuban believed the Pure Land exists in this world. He also taught that Vairocana is Amida.

Kakuban and his group of priests at the Denbō-in (伝法院) soon had conflicts with the leaders at Kongōbu-ji. Kongōbu-ji was the main temple at Mount Kōya. Through his connections with high-ranking nobles in Kyoto, Kakuban became the abbot of Mount Kōya. The leaders at Kongōbu-ji opposed him. After several conflicts, some of which involved burning down temples of Kakuban's group, Kakuban's followers left the mountain. They went to Mount Negoro to the northwest. There, they built a new temple complex now known as Negoro-ji (根来寺).

After Kakuban's death in 1143, attempts to make peace failed. After more conflicts, the Negoro group, led by Raiyu, founded the new Shingi Shingon School. This school was based on Kakuban's teachings. So, Shingon split into two main sub-schools: Kogi Shingon (古義真言宗, Ancient Shingon school) and Shingi Shingon (新義真言宗, Reformed Shingon school). Over time, these two Shingon sub-schools also disagreed on ideas. For example, they differed on how to achieve buddhahood through a single mantra. They also had different theories about how the Dharmakāya teaches the Dharma.

Following Kakuban, the Koyasan monk Dōhan 道範 (1179–1252) was important in promoting "esoteric Pure Land culture." This was a Shingon type of Pure Land Buddhism that became very popular. It influenced other figures and schools like Eison of Saidaiji's Shingon Risshu. This esoteric Pure Land culture included special uses and meanings of the nembutsu. It also popularized the use of the Mantra of Light.

During the Heian period, it became popular to include Shinto deities into Buddhism. This was known as Shinbutsu-shūgō (神仏習合, "syncretism of kami and buddhas"). This movement saw local Japanese deities as forms of the Buddhas. For example, Amaterasu was seen as a manifestation of Vairocana in Shingon. Buddhists called this idea honji suijaku. Major Shingon centers took part in this development. Important deities like Hachiman were worshipped at temples like Tō-ji.

Also during the Heian period, the mixed religion of Shugendō began to develop. Shingon's influence was a major part of its growth. Shingon especially influenced the Tōzan branch of Shugendō, which was centered on Mount Kinbu.

From Kamakura to Sengoku Periods

The Kamakura period (1185 to 1333) saw the rise of another new Shingon tradition, the Shingon-risshū school. This new tradition emphasized keeping monastic rules (Vinaya) along with esoteric practice. It was promoted by figures like Shunjō (1166–1227) and Eison (叡尊 1201–1290). Its center was Saidai-ji. Ninshō continued this tradition's work. It was known for many public projects, including building hospitals, hostels for the poor, and animal sanctuaries.

Also during this time, many followers of the Ji sect, founded by Ippen (1234–1289), made Kōya-san their home. They joined the Kōya hiriji groups. Many halls for Amida-centered Pure Land practice were built on the mountain.

During the Muromachi period (1336 to 1573), Shingon schools continued to grow. Some were supported by noble families or even emperors, like Go-Uda (1267–1324). He became a priest at Tō-ji and helped revive the temple and Daikaku-ji. Meanwhile, on Kōyasan, Yūkai (1345–1416) helped bring back Shingon doctrinal study. He also drove away all the nembutsu hiriji (who mostly followed the Ji sect) living on the mountain. He also removed all traces of the Tachikawa school, even burning their texts.

During the war-torn Sengoku period (1467 to 1615), all Shingon temples near the capital were destroyed or lost their lands. Shingon centers in the mountains like Kōya and Negoro had to raise armies for self-defense. Sometimes they used these forces to try to expand their temple lands. Mount Negoro, the center of Shingi Shingon, was attacked by the daimyō Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉) in 1585. After this show of force, Kōyasan, the last major Shingon temple standing, surrendered to Hideyoshi and was saved from destruction.

Edo Period and Beyond

During the Edo period (1603–1868), Shingi Shingon monks from Mount Negoro escaped and took their teachings elsewhere. They eventually founded new schools at Hase-dera (the Buzan school) and at Chishaku (the Chisan-ha school). In the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shogunate put in place new rules for Buddhist communities. Tokugawa Ieyasu issued regulations for the Shingon school in 1615. This brought it into the government's temple system. Under this new peace, Shingon study was revived in various temples. Hase-dera became a major center for studying all of Buddhism and also non-religious topics. Meanwhile, in Kōyasan, the Ji sect hiriji were allowed to return. They were included in the Shingon school, though this later led to conflict.

During this period, monks like Jōgen and Onkō (1718–1804) focused on studying and promoting Buddhist rules and monastic discipline. This new interest in rules was likely a response to criticisms of Buddhism from Confucian scholars at the time. Onkō was also a well-known scholar of Sanskrit.

After the Meiji Restoration (1868), the government forced a separation of Shinto and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri). It also ended the Chokusai Hōe (Imperial Rituals). The Shingon school was greatly affected by these changes. This was because it was closely connected with many Shinto shrines. It was also affected by the anti-Buddhist persecutions of the Meiji era, known as haibutsu kishaku. Some Shingon temples linked to Shinto shrines were turned into shrines. Some Shinto monks left the Buddhist priesthood to become Shinto priests, or they returned to regular life. The government took away temple land, which led to many Shingon temples closing. Those that survived had to rely on support from the general population.

During the Meiji period, the government also adopted a "one sect, one leader" rule. This forced all Shingon schools to merge under a single leader called a "Chōja" (Superintendent). This caused some internal political conflict among the different Shingon sub-schools. Some tried to form their own separate official sects. Some of these eventually succeeded in becoming independent. Eventually, the unified Shingon sect split into various sub-sects again.

Shingon in the 20th Century

In March 1941, the government's religious policy forced Shingon schools to merge into the 'Dai-Shingon' sect. During World War II, prayers for the surrender of enemy nations were often held at various temples. After the war, both Ko-Gyō and Shin-Gyō schools continued to separate. Some established their own unique teachings and traditions. Today, there are about eighteen major Shingon schools in Japan, each with its own main temple (honzan). Yamasaki estimated that in 1988, there were ten million Shingon followers and sixteen thousand priests in about eleven thousand temples. In Japan, there are also several new groups influenced by Shingon, classified as 'New Religions.' Some of these include Shinnyo-en, Agon-shu, and Gedatsu-kai.

Another recent development is that Chinese students are reviving Chinese Esoteric Buddhism by studying Japanese Shingon. This "tantric revival movement" (mijiao fuxing yundong 密教復興運動) was mainly spread by Chinese Buddhists. They traveled to Japan to train, be initiated, and receive teachings as acharyas in the Shingon tradition. Then they returned home to establish the tradition. Some important figures in this revival include Wang Hongyuan 王弘願 (1876–1937) and Guru Wuguang (悟光上師 (1918–2000). Both trained in Shingon and then spread Shingon teachings in Chinese-speaking areas.

Some of these Chinese acharyas chose to remain officially under the guidance of Kōyasan Shingon-shū or Shingon-shu Buzan-ha. They serve as Chinese branches of Japanese Shingon. But others chose to create independent schools. Today, these revival lineages exist in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Malaysia. Although they mainly draw from Shingon teachings, they have also adopted some Tibetan Buddhist elements.

A similar thing happened in South Korea. Two recent esoteric schools were founded there: the Chinŏn (眞言) and the Jingak Order (眞 覺). Both are largely based on Shingon teachings.

During the 20th century, Shingon Buddhism also spread to the West, especially to the United States. This move was led by the Japanese Diaspora. Now there are various temples on the West Coast and Hawaii. Examples include Hawaii Shingon Mission (built 1915–1918) and Koyasan Beikoku Betsuin in Los Angeles (founded 1912). Others are Henjyoji Shingon Temple in Portland, Oregon (established 1949), and the Seattle Koya'sn Temple in Seattle, Washington.

What Shingon Teaches

Key Texts and Ideas

The teachings of Shingon come from Mahayana texts and early Buddhist tantras. The most important secret texts are the Mahāvairocana Sūtra (大日経, Dainichi-kyō), the Vajraśekhara Sūtra (金剛頂経, Kongōchō-kyō), and the Susiddhikara Sūtra (蘇悉地経, Soshitsuji-kyō). Important Mahayana sutras in Shingon include the Lotus Sutra, the Brahmajāla Sūtra, and Heart Sutra. Kūkai wrote explanations for all three.

Shingon comes from the early period of Indian Vajrayana (then called Mantrayana, the Vehicle of Mantras). Unlike Tibetan Buddhism, which focuses on later tantras, Shingon uses earlier works like the Mahavairocana. These earlier texts generally do not include certain practices found in later tantras. However, the idea of "great bliss" and changing desires into wisdom is found in Shingon.

Another important text in Shingon is the Prajñāpāramitānaya-sūtra (Japanese: Hannyarishukyō). This is a later "tantric" Prajñaparamita sutra with 150 lines. It was translated by Amoghavajra. It contains verses and special syllables that summarize the Prajñaparamita teaching. The Hannyarishukyō is used a lot in Shingon for daily chanting and rituals.

Another key source for the Shingon school is the Awakening of Faith. There is also a commentary on it called the On the Interpretation of Mahāyāna (Japanese: Shakumakaen-ron). This was traditionally thought to be written by Nagarjuna, but it was likely written in East Asia.

Finally, Kūkai's own writings are very important in Shingon Buddhism. These include his explanations of the main esoteric texts of Shingon. They also include his original works like his big book, the ten-volume Jūjū shinron (Treatise on Ten Levels of Mind), and the shorter summary Hizō hōyaku (Precious Key to the Secret Treasury).

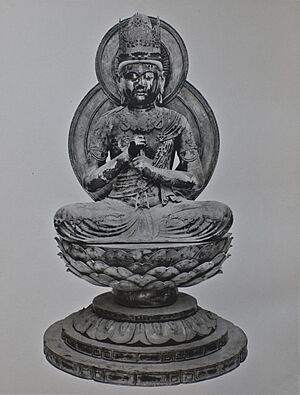

Mahāvairocana Buddha: The Great Illuminator

In Shingon, the Buddha Mahāvairocana (meaning "Great Illuminator" in Sanskrit) is also known as Dainichi Nyorai (大日如来, "Great Sun Tathagata"). He is the universal, original Buddha who is the basis of everything. Śubhakarasiṃha's Darijing shu says that Mahāvairocana is "the original dharmakāya." Kūkai believed the Dharmakaya is the "eternal Dharma," which is uncreated, never-ending truth.

This ultimate reality is not separate from things; it is present in them. Dainichi is worshipped as the highest Buddha. He also appears as the main figure of the Five Wisdom Buddhas. In Shingon, Dainichi is "at the center of many Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and powers." He is the source of enlightenment and the unity behind all differences. To become enlightened means to realize Mahāvairocana. This means Mahāvairocana is already inside every person.

Kūkai said that the Buddha's light shines and fills everything, like the sun's light. This presence also means that everyone already has "original enlightenment" (hongaku) within them. This is also called the "enlightened mind" (bodhicitta) and the Buddha nature. Kūkai wrote: "Where is the Dharmakaya? It is not far away; it is in our body. The source of wisdom? In our mind; indeed, it is close to us!"

Because of this, it is possible to "become Buddha in this very embodied existence" (sokushin jōbutsu). This is true even for people who seem very bad. All beings can become Buddhas through their own effort and through the Buddha's power or grace (adhisthana). Kūkai did not believe we lived in a time of Dharma decline. He thought we did not need to be reborn in a pure land to reach enlightenment. This also explains his positive view of the natural world and the arts. He saw all of them as forms of the Buddha.

The Buddha's Wisdom and Forms

Dainichi is the ultimate source of all Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and the entire universe. Dainichi is central because he is at the heart of both the Diamond Realm and the Womb Realm mandalas. Kūkai taught that Mahāvairocana is also the universal principle behind all Buddhist teachings. So, other Buddhist deities can be seen as forms of Dainichi, each with their own qualities. Kūkai wrote, "the great Self is one, yet can be many."

Like in the Huayan (Kegon) school, Shingon sees Dainichi's body as being the same as the entire universe. As Dharmakaya (Japanese: hosshin, Dharma body), Vairocana also constantly teaches the Dharma in amazing ways throughout the universe. This includes through the secret mysteries of Shingon esotericism. The Dharmakaya is the absolute reality and truth. It is mostly beyond words, but you can experience it through esoteric practices like mudras and mantras. Ultimately, the whole world and all its sounds and movements are also considered the teaching of Vairocana Buddha. This is the same as the cosmic body of the Buddha. So, for Kūkai, the entire universe, with all its actions, people, and Buddhas, is part of Vairocana's cosmic sermon to its own forms. In Shingon, this idea that all things in the universe constantly show the presence of the Dharmakaya Buddha is called "the dharmakaya's expounding of the Dharma" (hosshin seppō). Also, according to the syncretic idea of honji suijaku, the Shinto sun goddess Amaterasu was seen as a form of Dainichi Nyorai, along with other Shinto deities.

Kūkai explained the Dharmakaya as having four main bodies (shishu hosshin):

- Absolute Dharmakaya (jishō hosshin): This is the ultimate wisdom body of all Buddhas, from which the entire universe appears.

- Dharmakaya in Bliss / Participation (juyō hosshin): This has two parts. The bliss part is a state of perfect meditation. The participation part is how the Dharmakaya appears as Buddha forms to the most advanced bodhisattvas.

- Transformation Dharmakaya (henge hosshin): This is how the Buddha appears to lower-level bodhisattvas, students, and ordinary people. This includes the historical Buddha Shakyamuni.

- Emanation Dharmakaya (tōru hosshin): These are bodies coming from the Dharmakaya in many forms, including non-human beings and hell beings.

Even though it uses human-like descriptions, Shingon does not see the Dharmakaya Buddha as a separate person or a God apart from the universe. Instead, the Buddha is the universe when understood correctly.

The Wisdom of the Dharmakaya

Another important part of the Dharmakaya in Kūkai's teachings is his idea of Vairocana's body of wisdom (chishin). According to this teaching, the Dharmakaya has five wisdoms. Each one is linked to a Buddha. Four of them are linked to a type of everyday consciousness (from the Yogacara system of eight consciousnesses):

- The Wisdom that Sees the True Nature of the Dharma World (hokkai taishō chi): This is the eternal source of knowledge and light at the center of everything. It is shown by Mahāvairocana Buddha in the Vajradhatu Mandala.

- Mirror-like Wisdom (daienkyō): This wisdom reflects things exactly as they are, without any changes. It is shown by Aksobhya Buddha and is linked to the alaya-vijñana (storehouse consciousness).

- Wisdom of Equality (byōdōshō chi): This wisdom sees that all things and beings are the same and connected. It is shown by Ratnasambhava Buddha and is linked to the ego consciousness (manas).

- Wisdom of Observation (myōkanzatchi): This wisdom is free from judging and sees all objects of the mind without bias. It is shown by Amitabha and is linked to the mental consciousness (manovijñana).

- Wisdom of Action (jōsosa chi): This wisdom shows up as actions that help all living beings and guide them to Buddhahood. It is shown by Amoghasiddhi and is linked to the five senses.

In the Vajrasekhara Sutra, the light of the Buddha's wisdom body is shown as a vajra. This is Indra's unbreakable, diamond-like weapon. It represents the strong power of deep insight. In the Mahavairocana Sutra, the Buddha's Body of Principle (Japanese: ri) is shown by a lotus. This stands for "compassion, potential, growth, and creativity." For Kūkai, both of these bodies are not separate. Kūkai wrote: "That which realizes is Wisdom and that which is to be realized is Principle. The names differ, but they are one in their essential nature."

The Six Elements, Four Mandalas, and Three Mysteries

Kūkai also explained the Dharmakaya using the "Body of Six Great Elements" (rokudaishin). This means that for Kūkai, the Dharmakaya is made of the six great elements. These elements "are mixed together and are in perfect harmony forever." The great elements (mahābhūtani) are earth, water, fire, wind, space, and consciousness. They are the universal parts that make up all beings and matter. These great elements are all perfectly mixed (yuanrong, 圓融), meaning they are all connected in harmony. This idea was first explained in the Huayan school by teachers like Fazang. Like Fazang, Kūkai used the idea of Indra's Net to describe how everything in existence is infinitely connected. This means that the Dharmakaya Mahāvairocana and every living being in the universe "are not identical but are nevertheless identical; they are not different but are nevertheless different."

For Kūkai, this teaching means that there is no real separation between things that seem different. For example, mind and matter, humans and nature, living and non-living things, are all connected. Kūkai wrote: "matter is no other than mind; mind is no other than matter. Without any obstruction, they are interrelated." This connection is one of great harmony, an eternal natural order (hōni no dōri). This order is the same as the yoga and samadhi of the Dharmakaya. Living beings are small versions of the Dharmakaya. They can connect to this harmony by practicing meditation.

Another way to understand the Dharmakaya is through the four mandalas. These are circles or spheres that represent the cosmic Buddha Vairocana's reach, purpose, communication, and action:

- Mahāmandala: This is the entire physical universe as the body of the Dharmakaya Buddha.

- Samayamandala: This is the ultimate purpose of the Dharmakaya Buddha. It is present everywhere in the universe and is universal compassion.

- Dharmamandala: This is the universal area where the Dharmakaya Buddha is teaching and revealing the Dharma.

- Karmamandala: These are the universal activities of the Dharmakaya Buddha, meaning all the movements of the universe.

These four mandalas are all deeply connected. Kūkai wrote that they are "inseparably related to one another."

The constant teaching of the Dharmakaya Buddha throughout the universe is described in Shingon as the "three mysteries" (sanmi 三密). These are the special activities or functions of the Body, Speech, and Mind of Mahāvairocana. The three mysteries are found throughout the entire universe. They appear as the movements of nature, natural sounds, and all experiences. Kūkai compared it to a sacred book "being painted by brushes of mountains, by ink of oceans," with heaven and earth as the covers.

The connected nature of all mandalas and how all things are part of Mahavairocana's body and functions is a key Shingon idea. It also explains how the practice of the three secrets works. Through the Shingon "three-secrets yoga" (sanmitsu yuga), a practitioner connects their body, speech, and mind with those of the Buddha's Dharmakaya. Kūkai said that "the three secrets bring about the response of empowerment [kaji] and one quickly reaches great enlightenment."

Buddha's Power and Self-Power

The three mysteries also connect to the Buddha's energy, grace, or supporting power (Sanskrit: adhiṣṭhāna, Japanese: kaji). Kūkai said this "shows great compassion from the Buddha and faith (Sanskrit: citta-prasāda, Japanese: shinjin) from living beings." Kūkai compared this to sun rays (the Buddha's power) shining on water (living beings). The water can hold the heat of the rays. Kūkai also believed that faith comes from the Buddha's power; it is not something you get by yourself. In fact, for Kūkai, the three mysteries are natural in all beings. The fact that these are connected with the larger three mysteries of the Dharmakaya is what makes faith possible.

However, in Shingon, you don't only gain good karma and enlightenment through the Buddha's power. Instead, it happens through a combination of "the three powers" (sanriki):

- The power of Buddha's blessing or grace (nyorai kaji-riki), which is "other power" (tariki).

- Your own power of self-merit (ga kudoku-riki), which is "self-power" (jiriki).

- The power of the Dharma realm (hokkai riki), which is the connected true nature where self and Buddha are not separate.

So, in Shingon, self-power and other-power are not two separate powers but are connected.

Kūkai described this as "the Buddha entering the self and the self entering the Buddha" (nyūga ga'nyū). Yamasaki called this "a subtle process of the self, the deity, and the universe." He said that when striving "upward," the person feels an energy flowing "downward" as if to help their striving.

Becoming a Buddha

According to Shingon teaching, Buddhahood is not a far-off goal that takes ages to reach. It is something truly possible in this very life. This is because the buddha-nature or original enlightenment is already inside all beings. Kūkai described this inner reality in all beings as "the glorious mind, the most secret and sacred."

Kūkai said the main teaching on enlightenment in the Mahāvairocana sutra is in these passages: "The enlightened mind [bodhicitta] is the cause, great compassion [mahakaruna] is the root, and skillful means [upaya] is the ultimate...enlightenment is to know your own mind as it really is...Seek in your own mind enlightenment and all-embracing wisdom. Why? Because it is originally pure and bright." This means that Buddhahood can be reached because all beings already have enlightenment and "all embracing wisdom" within them. This wisdom is "originally pure and bright," according to Kūkai. With the help of a true teacher and proper training, one can rediscover and free this enlightened ability for their own benefit and for others. When developed, the bright enlightened mind shows up as awakened wisdom.

Kūkai organized all Buddhist teachings into ten stages of spiritual understanding. These ranged from the lowest worldly mind to the highest mind of exoteric Buddhism (the view of Huayan/Kegon) to the supreme mind reached through Shingon.

What Makes Esoteric Buddhism Special

Kūkai wrote a lot about the difference between exoteric (mainstream, non-tantric) Mahayana Buddhism and esoteric Mantrayana (or Vajrayana) Buddhism. For him, the differences can be summarized as follows:

- Esoteric teachings are given by the Dharmakaya Buddha, Vairocana. They are "secret & profound, containing the final truth." Exoteric teachings are given by nirmanakaya (emanation) Buddhas, like Shakyamuni. These are "simplified" skillful ways to teach. Exoteric Mahayana sutras also have hidden esoteric meanings that Kūkai discussed. For example, Kūkai considered the title of the Lotus Sutra a mantra.

- Kūkai believed that exoteric teachings were upāyas ("skillful means"). These were teachings adjusted to what people needed, based on their abilities and the time. Esoteric teachings, in contrast, are the truth itself. They are a direct sharing of the deepest secrets of the Dharmakaya and his timeless, always-present meditation.

- Exoteric teachings are gradual (and might take ages). Esoteric methods are the "sudden approach." Or, at least, they offer a much faster way to enlightenment. Even the most troubled beings can awaken through the simplest esoteric method: reciting a mantra.

- Esoteric Buddhism includes all the teachings of exoteric Buddhism, and more. Exoteric Buddhist schools do not have the special methods of esoteric Buddhism, which is the highest form of Buddhism. These esoteric rituals, using mantras, mudras, and mandalas, are the direct communication of the Dharmakaya. They provide direct access to the ultimate truth.

- Esoteric Buddhism has the highest view of ultimate truth. It sees the mind of Mahāvairocana as united with the mind of all beings. It also sees the body of Mahāvairocana as the body of the universe (which contains all living beings).

Shingon Practices

The main goal of Shingon is to realize that your true nature is the same as the universal Mahāvairocana Buddha. You achieve this through special initiation and mantrayana ritual practices. Shingon practice relies on receiving secret teachings, methods, and instructions from the school's ordained masters. The "Three Mysteries" of body, speech, and mind work together to reveal your true nature:

- Body: through devotional gestures (mudra) and ritual tools.

- Speech: through sacred formulas (mantra).

- Mind: through meditation.

These methods help a Shingon practitioner realize that their body and mind are the same as Mahāvairocana's body and mind.

The Three Mysteries and Consecration

The core of Shingon practice is to experience the Dharmakaya, which is the ultimate reality. You do this by imitating the inner realization of the Dharmakaya. This is done through synchronized meditative rituals using mantras, mudras (hand gestures), and visualizing mandalas. These are called the "three modes of action." They are the main methods of Shingon esoteric practice. These three "ritual technologies" are the same as the "three mysteries"—the secrets of the body, speech, and mind of the Buddha Vairocana. These are introduced in the ritual of abhisheka (consecration), where special tantric vows (samaya) are made by those being initiated. As the Indian Shingon master Śubhākarasiṃha said: "the three modes of action are simply the three secrets, and the three secrets are simply the three modes of action. The three [Buddha] bodies are simply the wisdom of tathāgata Mahavairocana."

The abhisheka involves entering a special ritual space with a mandala while blindfolded. You throw a flower into the mandala, and it lands on a specific deity shown in the mandala. After this consecration, the initiated person learns how to visualize the deities and mandalas. They also learn the secret mudras and mantras of their deity. These secrets are revealed to be the expression of the Buddha's body, speech, and mind. Through this consecration and the use of these three mysteries, the initiated person is said to ritually copy the Buddha's body, speech, and mind, achieving buddhahood in this very life.

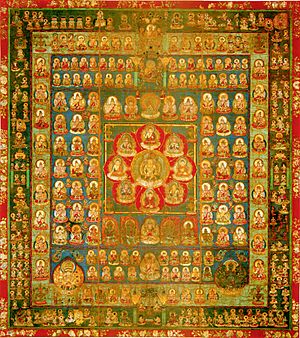

Mandalas: Visualizing the Universe

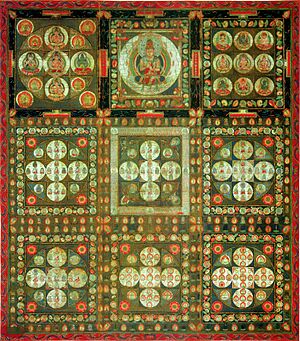

Visualizing a mandala matches the mental activity of the Buddha. The most important Shingon mandalas are the Mandala of the Two Realms. These are:

- The Womb Realm (Sanskrit: Garbhadhātu; Japanese: 胎蔵界曼荼羅, romanized: Taizōkai) mandala, based on the Mahavairocana Sutra.

- The Diamond Realm (Sanskrit: Vajradhātu; Japanese: 金剛界曼荼羅, romanized: Kongōkai) mandala, based on the Vajrasekhara Sutra.

These two mandalas are seen as a complete expression of Buddhahood and a representation of all existence.

The "Great Compassion Womb Repository Birth Mandala" represents the enlightened universe from the viewpoint of compassion. It is also linked to skillful means, and the lotus is its main symbol. The Vajra Realm mandala "embodies the vajra-wisdom that illuminates the universe." This is the Buddha's wisdom body, which is unbreakable like the mythical diamond weapon (vajra). While the womb realm generally represents the five material elements, the vajra realm represents the mind and consciousness elements. However, both mandalas are not separate; they are ultimately seen as one. So, "the two mandalas together thus signify the unbreakable unity of Truth and Wisdom, the inseparability of Matter and Mind, the resolution of mystical paradox."

Mantras: Sacred Sounds

Mantras are another key part of Shingon practice. They represent the speech of the Dharmakaya Buddha. Kūkai understood mantras as the most concentrated form of the Dharmakaya Buddha's teachings. According to Kūkai, Shingon mantras contain the full meaning of all scriptures and indeed the entire universe. The universe itself is the preaching of the Dharmakaya. Kūkai argued that mantras work because: "a mantra is beyond reason; it removes ignorance when meditated upon and recited. A single word contains a thousand truths; one can realize Suchness here and now."

Kūkai also stated: "By reciting the voiced syllables with clear understanding, one shows the truth. What is called 'the truth of the voiced syllable' is the three secrets where all things and the Buddha are equal. This is the original essence of all beings. For this reason, Dainichi Nyorai's teaching of the true meaning of the voiced syllable will awaken those who have been sleeping for a long time."

So, mantras are not just simple chants. They show the Buddha's power and blessings, being full forms of the Buddha. According to the Commentary to the Mahavairocana Sutra: "The reason that only the Mantra Gate fulfills the secret is that [ritual is performed] by empowerment with the truth. If mantras are recited only in one's mouth, without thinking about their meaning, then only their worldly effect can be accomplished – but the adamantine body-nature cannot."

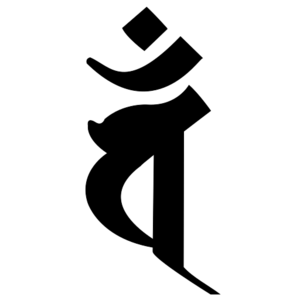

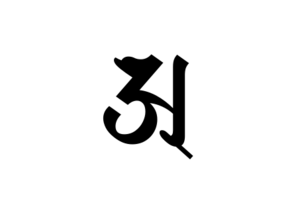

Mantras (and bījas, or "seed-syllable" mantras) are usually linked to a Buddhist deity. For example, the seed syllable of Mahavairocana in the Garbhadhātu Mandala is "A". A key mantra of Mahavairocana is "a vi ra hūṃ kha". Some deities have multiple seed mantras and different mantras.

In Shingon, mantras (as well as dharanis, vidyas, etc.) are written in Sanskrit, using the Siddhaṃ alphabet (Japanese: shittan 悉曇, or bonji 梵字). However, the pronunciation of mantras is in a Sino-Japanese style, not any Indian style of Sanskrit pronunciation.

Mudras: Hand Gestures

Mudras ("seals") are hand gestures that represent the secret of the Buddha's body. They symbolize and perform Buddha activity. Many mudras are used in various Shingon practices. Mudras "symbolically connect the individual with the universe." In this way, the human body acts as a living symbol of the larger universe. The word mudra can have several meanings. In some cases, it is a very general term referring to the Buddha's Dharmakaya (then called the "great mudra," mahamudra). The Commentary on the Mahavairocana sutra states: "Mudra is none other than a symbol of the Dharma Realm. Using mudra, one points to the body of the Dharma Realm."

The hand gestures themselves are either called samaya mudra (when it refers to a deity's item, like a sword or lotus) or karma mudra (when it symbolizes their activity). Each hand and finger has different symbolic meanings in Shingon. For example, the right hand usually represents the Buddha, while the left hand symbolizes ordinary beings, including the practitioner. Other meanings include: right hand: Wisdom, Buddha-Realm, Sun, and Vajra Realm mandala; left hand: Truth, Phenomenal Realm, Moon, and Womb Realm mandala. The fingers can represent the five senses and the five elements.

A key mudra is the añjali mudrā (Japanese: gasshō). This symbolizes the unity of the Buddha realm with the world of phenomena and living beings. There are different forms of the gasshō besides the standard palm-to-palm version, including the lotus gasshō and the vajra gasshō. Another important mudra in Shingon (also used in other traditions like Zen) is the "Dharmadhatu Samadhi" mudra (hokkai jō-in). This symbolizes the union of self with Buddha, and the phenomenal world with the Buddha Realm. The "Wisdom Fist" (chiken-in) mudra also shows the unity of Buddha and living beings. In this mudra, the breath of life (the index finger on the left hand, representing air) touches the all-encompassing emptiness (the thumb tucked within the right fist, representing space). This also symbolizes the Buddha's wisdom, which is connected to emptiness and is everywhere.

Meditation and Chanting

Another important meditation practice in Shingon is Ajikan (阿字觀), which means "meditating on the letter A" (Template:Devanagari अ, Siddham: 𑖀). This letter is written using the Siddhaṃ alphabet. The letter A is an important symbol in Mahayana and esoteric Buddhism. It represents the Dharmakaya, the Buddha Mahavairocana, emptiness, Prajñaparamita, and non-arising (anutpada). While Kūkai's writings discuss the letter A and its importance for esoteric practice, they don't give step-by-step meditation instructions. The earliest detailed source for this practice is Jitsue's (実恵, 786–849) Record of Oral Instruction on the Ajikan (Ajikan yōjin kuketsu). It describes meditating on the letter "A" inside a white moon disk, which sits on a lotus flower. The moon represents the awakened mind (bodhicitta), and the lotus represents the heart (hrdaya). Since then, over a hundred Ajikan manuals have been written, and Ajikan has become a central practice in the Shingon school.

There are other forms of Shingon practice. For example, in Gachirinkan (月輪觀, "Full Moon Visualization"), an image of the moon (an important symbol of the enlightened mind) is used for visualization. In Gojigonjingan (五字嚴身觀, "Visualization of the Five Elements Arrayed in the Body," from the Mahavairocana Tantra), the focus is on the five elements (mahābhūtani) as forms of the Buddha Vairocana.

Shingon Buddhist temples also perform religious rites. These include chanting sutras and other liturgy. This may be done with instruments like the taiko drum. A popular style of Buddhist chanting in Shingon is called shōmyō (声明), a style influenced by traditional Japanese music.

Shingon practice may also include nembutsu or other methods linked to Amitabha and his Pure Land. In Shingon, this practice is understood through esoteric Buddhism. This means seeing the Buddha Amitabha (who is seen as Mahavairocana) as being present in the human "heart-mind." The pure land of Sukhavati is seen as not separate from this world. "Esoteric Pure Land" practice was taught by Shingon figures like Kakuban (1095–1143) and Dōhan (1179–1252).

Various Chinese masters also taught chants related to Amitabha. For example, Amoghavajra translated the popular "Amitabha Pure Land Rebirth Dharani," along with many other texts that teach ways to be reborn in Sukhavati.

Ethical Rules

Another important part of Shingon practice is following Buddhist ethical rules (kai). For Kūkai, keeping Buddhist rules is essential for meditation and for living in harmony with one's true nature. Kūkai wrote: "If we want to go far, we cannot advance unless we use our feet; if we wish to walk the Way of Buddha, we cannot reach the goal unless we follow the rules." He even said that we should not break the rules even to save our lives. He also said that those who break them are not disciples of the Buddha, and he would not be their teacher.

Shingon ethical teachings are based on the basic Buddhist rules. These include Mahayana bodhisattva precepts (from the Brahmajala Sutra) along with special mantrayana esoteric vows (samayas). According to Kūkai, "all of these precepts are based on the Ten Precepts." These are the ten wholesome dharma paths. Furthermore, the main idea of all the rules is that "the true nature of our mind is not different from that of the Buddha."

Regarding the esoteric vows (samayas), there are four main ones in Shingon:

- Never giving up the True Dharma. You should master all the Buddha's teachings without abandoning any.

- Never giving up bodhicitta. This means both the intention to become a Buddha for all beings and the original enlightened mind itself. These two aspects are seen as connected. This is the most important vow for Kūkai.

- Never holding back or being "tight-fisted" about teaching the Dharma to others. You must always share the Dharma.

- Never avoid helping living beings (and never harm them). This is especially done through the "four embracing acts" (generosity, loving words, beneficial acts, adapting oneself to others' needs).

Learning from a Teacher

Besides basic meditations, prayers, and reading Mahayana sutras, there are mantras and ritual meditation techniques. Laypeople can practice these on their own under the guidance of a Shingon priest (ajari 阿闍梨, from Sanskrit: ācārya). However, many esoteric practices require the student to receive an abhiṣeka initiation (kanjō 灌頂) for each practice. This must be done under the guidance of a qualified ācārya before they can start learning and practicing them. Like all schools of Esoteric Buddhism, there is a strong focus on initiation and oral transmission of teachings from teacher to student.

So, all Shingon followers who want to practice the esoteric methods must slowly build a teacher-student relationship. This can be formal or informal. A teacher who is allowed to give the abhiseka (a mahācārya, Japanese: dai-ajari) learns about the student and teaches esoteric practices accordingly. For lay practitioners, there is a special initiation ceremony called the Kechien Kanjō (結縁灌頂). This aims to help create a bond between the follower and Mahavairocana Buddha.

Training for Teachers

If students want to train to become a Shingon ācārya (esoteric master), they must first complete a period of academic study and religious discipline. Or, they can have formal training in a temple for a longer time. They must also have already received novice ordination and monastic rules. Additionally, they must fully complete the rigorous four-part preliminary training and retreat known as shido kegyō (四度加行). This must be done under the guidance of a qualified master. The training involves esoteric rites focused on calling upon specific buddhas or bodhisattvas (the honzon or “principal deity”). It also includes pilgrimages to holy sites. These complex rites are taught through oral transmission (kuden) between a master and a student. This process is helped by many ritual manuals and texts. The specific details of each rite may differ depending on the lines of transmission (ryu).

An ācārya in Shingon is a dedicated and experienced teacher. They are authorized to guide and teach practitioners. In the Kōyasan tradition, one must be an ācārya for several years before they can ask to be tested at Mount Kōya. This test is for the possibility to qualify as a mahācārya, or "great teacher" (dento dai-ajari 傳燈大阿闍梨). This is the highest rank in Shingon practice.

However, other Shingon schools outside the Kōyasan tradition may use different terms. For them, the term dai-ajari might not have such a special meaning. It is also possible that the special dai-ajari rank at Kōyasan developed after Kūkai.

Goma Fire Ritual

The goma (護摩) fire ritual is an important and well-known ritual in Shingon. Goma has roots in the Vedic homa ritual. Traditional writers like Yi Xing (8th century) recognized this. According to Yi Xing: "Buddha created this teaching to convert non-Buddhists and help them tell true from false. So he taught them the true Goma[...] The Buddha himself taught the very foundation of the Vedas. In that way, he showed the correct principles and method of the true Goma. This is the 'Buddha Veda'."

So, while the Goma looks like Vedic rituals, if understood correctly, it shares the Buddha's true inner meaning. According to the Commentary on the Mahavairocana Sutra: "The meaning of goma is to burn the firewood of confusion with the wisdom flame, consuming it completely."

Qualified priests and acharyas perform Goma for the benefit of individuals, the state, or all living beings. The sacred fire is believed to have a strong cleansing effect. Esoteric Buddhist sources like Yi Xing see the goma fire as the purifying wisdom of the Buddha. So, the ritual is performed to destroy harmful thoughts and desires. It is also used for making everyday requests and blessings. The main deity called upon in this ritual is usually Acala (Fudō Myōō 不動明王). The ritual is performed in most major Shingon temples. Larger ceremonies often include the constant beating of taiko drums and mass chanting of Acala's mantra by priests and lay practitioners.

Followers of the mixed Japanese religion of Shugendō (修験道) also practice the goma ritual, adopting it from Shingon Buddhism. Two types are common: the saido dai goma and hashiramoto goma rituals. The goma ritual was also adopted by other schools of Japanese Buddhism, and it is still practiced in some Zen temples.

Pilgrimage to Holy Sites

The practice of making pilgrimages to holy sites, especially mountains seen as homes of deities, grew throughout Shingon's history. Many pilgrimage routes are still a key part of Shingon practice today. One such route is the Shikoku Pilgrimage. This pilgrimage is linked to devotion to Kūkai and includes a total of 88 places.

Important Deities in Shingon

The Shingon pantheon includes many Buddhist deities. Many of these deities play important roles. Practitioners regularly call upon them for various rituals like the homa fire ritual and in religious services.

In Shingon, divine beings are grouped into six main classes: Buddhas (Butsu 仏), Bodhisattvas (Bosatsu 菩薩), Wisdom Kings (Vidyaraja, Myōō 明王), Devas (Ten 天), Buddha emanations (Sanskrit: nirmāṇakāya, Keshin 化身), and Patriarchs (Soshi 祖師).

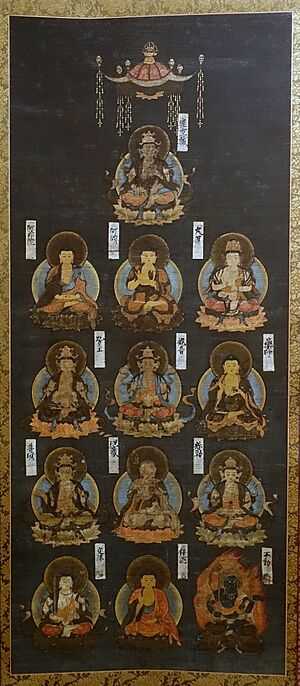

The Thirteen Buddhas

The most important group of deities in Shingon is called the Thirteen Buddhas (十三仏, Jūsanbutsu). This group actually includes Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and Wisdom Kings found in the womb-realm and vajra-realm mandalas.

They are widely called upon in several religious services and rituals. This includes the popular Thirteen Buddha Rites (jūsan butsuji 十三仏事). These rites are linked to the deceased and to gaining merit. Each figure also has their own mantra and seed syllable in Shingon, which are used in these rituals. Thirteen Buddha Rites became popular throughout Japanese Buddhism during the Edo Period.

The thirteen buddhas (more accurately "thirteen deities") along with their mantras and seed syllables (bīja) are:

- Wisdom King Acala (Fudō Myōō 不動明王), Bīja: Hāṃ; Sanskrit mantra: namaḥ samanta vajrāṇāṃ caṇḍa mahāroṣaṇa sphoṭaya hūṃ traṭ hāṃ māṃ (Shingon transliteration: nōmaku samanda bazaratan senda makaroshada sowataya untarata kanman)

- Gautama Buddha (Shaka-Nyorai 釈迦如来), Bīja: Bhaḥ; Mantra: namaḥ samanta buddhānāṃ bhaḥ (nōmaku sanmanda bodanan baku)

- Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva (Monju-Bosatsu 文殊菩薩), Bīja: Maṃ; Mantra: oṃ a ra pa ca na (on arahashanō)

- Samantabhadra Bodhisattva (Fugen-Bosatsu 普賢菩薩), Bīja: Aṃ; Mantra: oṃ samayas tvaṃ (on sanmaya satoban)

- Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva (Jizō-Bosatsu 地蔵菩薩), Bīja: Ha; Mantra: oṃ ha ha ha vismaye svāhā (on kakaka bisanmaei sowaka)

- Maitreya Bodhisattva (Miroku-Bosatsu 弥勒菩薩), Bīja: Yu; Mantra: oṃ maitreya svāhā (on maitareiya sowaka)

- Bhaiṣajyaguru Buddha (Yakushi-Nyorai 薬師如來), Bīja: Bhai; Mantra: oṃ huru huru caṇḍāli mātangi svāhā (on korokoro sendari matōgi sowaka)

- Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva (Kannon-Bosatsu 観音菩薩), Bīja: Sa; Mantra: oṃ ārolik svāhā (on arorikya sowaka)

- Mahāsthāmaprāpta Bodhisattva (Seishi-Bosatsu 勢至菩薩), Bīja: Saḥ; Mantra: oṃ saṃ jaṃ jaṃ saḥ svāhā (on san zan saku sowaka)

- Amitābha Buddha (Amida-Nyorai 阿弥陀如来), Bīja: Trāḥ; Mantra: oṃ amṛta teje hara hūṃ (on amirita teisei kara un)

- Akṣobhya Buddha (Ashuku-Nyorai 阿閦如来), Bīja: Hūṃ; Mantra: oṃ akṣobhya hūṃ (on akishubiya un)

- Mahavairocana Buddha (Dainichi-Nyorai 大日如来), Bīja: A; Mantra: oṃ a vi ra hūṃ khaṃ vajradhātu vaṃ (on abiraunken basara datoban)

- Ākāśagarbha Bodhisattva (Kokūzō-Bosatsu 虚空蔵菩薩), Bīja: Trāḥ; Mantra: namo ākāśagarbhāya oṃ ārya kāmāri mauli svāhā (nōbō akyasha kyarabaya on ari kyamari bori sowaka)

Other Important Deities

The "Five Great Wisdom Kings" (Godai Myō-ō, 五大明王) are fierce forms of the Five Buddhas:

- Acala or Acalanatha (Fudō Myōō 不動明王) "The Immovable One" – Form of Buddha Mahavairocana

- Amrtakundalin (Gundari Myōō 軍荼利明王) "The Dispenser of Heavenly Nectar" – Form of Buddha Ratnasambhava

- Trailokyavijaya (Gōzanze Myōō 降三世明王) "The Conqueror of The Three Planes" – Form of Buddha Akshobhya

- Yamāntaka (Daiitoku Myōō 大威徳明王) "The Defeater of Death" – Form of Buddha Amitabha

- Vajrayaksa (Kongō Yasha Myōō 金剛夜叉明王) "The Devourer of Demons" – Form of Buddha Amoghasiddhi

There are many Indian Buddhist deities in the Shingon pantheon and in Shingon mandalas. These include figures like Indra (Taishakuten 帝釈天), Prthivi (Jiten 地天, Goddess of the Earth), Maheshvara (Daijizaiten 大自在天 or Ishanaten 伊舎那天), Marici (Marishi-Ten 摩里支天), Mahakala (Daikokuten 大黒天 Patron deity of Wealth), and Saraswati (Benzaiten 弁財天 Patron deity of Knowledge, Art and Music).

Besides Indian Buddhist deities, many Shinto deities were also included in Shingon Buddhism. These include Hachiman, Inari Ōkami, and the sun goddess Amaterasu.

Shingon Lineage

The Shingon lineage is an ancient transmission of esoteric Buddhist teachings. It began in India and then spread to China and Japan. Shingon, or Orthodox Esoteric Buddhism, believes that the original teacher of the doctrine was the Universal Buddha Vairocana. However, the first human to receive the teaching was Nagarjuna in India. Like all major East Asian Buddhist traditions, the Shingon tradition created a list of "patriarchs." These were considered the key figures in passing down their lineage. Shingon recognizes two groups of eight great patriarchs: one group of lineage holders and one group of great teachers of the doctrine.

- The Eight Great Doctrine-Expounding Patriarchs (Fuho-Hasso 付法八祖)

- Amoghavajra (Fukūkongō-Sanzō 不空金剛三蔵)

- Huiguo (Keika-Ajari 恵果阿闍梨)

- Kūkai (Kōbō-Daishi 弘法大師)

- Nagabodhi (Ryūchi-Bosatsu 龍智菩薩)

- Nagarjuna (Ryūju-Bosatsu 龍樹菩薩) – received the Mahavairocana Tantra from Vajrasattva inside an Iron Stupa in Southern India

- Vairocana (Dainichi-Nyorai 大日如来)

- Vajrabodhi (Kongōchi-Sanzō 金剛智三蔵)

- Vajrasattva (Kongō-Satta 金剛薩埵)

- The Eight Great Lineage Patriarchs (Denji-Hasso 伝持八祖)

- Amoghavajra (Fukūkongō-Sanzō 不空金剛三蔵)

- Huiguo (Keika-Ajari 恵果阿闍梨)

- Kūkai (Kōbō-Daishi 弘法大師)

- Nagabodhi (Ryūchi-Bosatsu 龍智菩薩)

- Nagarjuna (Ryūju-Bosatsu 龍樹菩薩)

- Śubhakarasiṃha (Zenmui-Sanzō 善無畏三蔵)

- Vajrabodhi (Kongōchi-Sanzō 金剛智三蔵)

- Yi Xing (Ichigyō-Zenji 一行禅師)

Shingon Schools and Branches

In Japan, the Shingon initiation and practice lineages, known as hōryū 法流, developed into two main streams: Ono-ryū 小野流 and Hirosawa-ryū 廣澤流. Each of these has many schools and sub-lineages.

When the Tokugawa Shogunate started to control temple complexes more in 1601, both exoteric and esoteric traditions were affected. To follow government rules, Shingon temples emphasized the differences between Kogi Shingon 古義真言宗 and Shingi Shingon 新義真言宗. These differences were linked to the distinct temple complexes on Kōyasan and the Chisan and Buzan temples. These distinctions became like "brand names" for "Old Doctrine" Shingon and "New Doctrine" Shingon, even though their basic teachings and rituals were not very different. Also, even though the Tokugawa government set up temple hierarchies in the 17th century, the connections between Shingon schools remained very close. For example, temple networks linked to Kogi temples like Daigoji or Tōji stayed connected, even if they formally became part of Shingi Shingon. These connections crossed sectarian lines because the temples had been linked through their ritual lineages since medieval times. They only later identified themselves as Kogi or Shingi.

- The Orthodox (Kogi) Shingon School (古義真言宗)

- Kōyasan (高野山真言宗)

- Reiunji-ha (真言宗霊雲寺派)

- Zentsūji-ha (真言宗善通寺派)

- Daigo-ha (真言宗醍醐派)

- Omuro-ha (真言宗御室派)

- Shingon-Ritsu (真言律宗)

- Daikakuji-ha (真言宗大覚寺派)

- Sennyūji-ha (真言宗泉涌寺派)

- Yamashina-ha (真言宗山階派)

- Shigisan (信貴山真言宗)

- Nakayamadera-ha (真言宗中山寺派)

- Sanbōshū (真言三宝宗)

- Sumadera-ha (真言宗須磨寺派)

- Tōji-ha (真言宗東寺派)

- Ishizuchisan(石鎚山真言宗)

- The Reformed (Shingi) Shingon School (新義真言宗)

- Shingon-shu Negoroji (根来寺)

- Chizan-ha (真言宗智山派)

- Buzan-ha (真言宗豊山派)

- Kokubunji-ha (真言宗国分寺派)

- Inunaki-ha (真言宗犬鳴派)

See also

- Chinese Buddhism

- Eastern esotericism

- Religion in Asia

- Religion in Japan

- Shinjō Itō

- Shinnyo-en

- Sokushinbutsu

- Tangmi