George Washington and slavery facts for kids

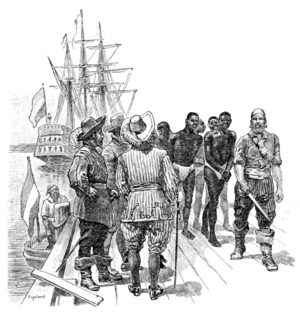

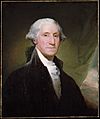

The story of George Washington and slavery shows how his views on owning people changed over time. Washington was a very important Founding Father of the United States. He inherited enslaved people from his family. Slavery had been a common practice for over a hundred years in Virginia, where he lived. It was also common in other American colonies and around the world.

Washington eventually became uncomfortable with slavery. In his will, he arranged for one enslaved person to be freed right away. He also said that the other 123 enslaved people he owned would serve his wife, Martha, until her death. They were then freed about a year after Washington passed away.

Contents

Early Life and Inheriting Slavery

Slavery was a big part of life and the economy in Virginia when Washington was growing up. His family had owned enslaved people for generations. When he was only 11 years old, his father died in 1743. George Washington then inherited his first ten enslaved people.

As an adult, he gained more enslaved people. This happened through inheritance, by buying them, and because children born to enslaved mothers were also considered enslaved. In 1759, when he married Martha Dandridge Custis, he gained control of additional enslaved people. These were part of Martha's first husband's estate, called "dower slaves." At first, Washington's ideas about slavery were like most other wealthy landowners in Virginia. He didn't seem to have strong moral concerns about it.

However, in 1774, Washington publicly spoke out against the slave trade. He said it was wrong. After the Revolutionary War, he privately supported ending slavery little by little through new laws. Even with these changing views, he still relied on enslaved workers for his farms.

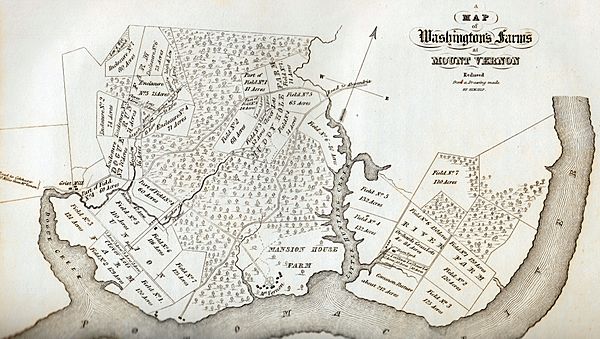

Life for Enslaved People at Mount Vernon

Washington believed in hard work. He expected both his paid workers and the enslaved people to work very hard. He provided basic food, clothing, and housing for the enslaved people. This was similar to what was common at the time, but it was not always enough. He also provided some medical care.

Enslaved people were forced to work from sunrise to sunset, six days a week. About three-quarters of them worked in the fields. The rest worked in the main house as servants or as skilled workers like blacksmiths. They often found ways to get extra food by hunting or growing vegetables in their free time. They also earned money by selling game or produce. This money helped them buy more food, clothes, or household items.

Enslaved people built their own communities through marriage and family. However, Washington often moved enslaved people to different farms based on his business needs. This meant many husbands and wives lived apart during the work week. Washington used both rewards and punishments to manage the enslaved population. He often felt disappointed when they did not meet his high expectations. Many enslaved people at Mount Vernon resisted their enslavement. They did this by stealing food or clothing, pretending to be sick, or trying to escape.

Washington's Views During and After the War

In 1775, when Washington became the leader of the Continental Army, he first refused to let African Americans join. But as the war continued, he changed his mind. He then led an army that included soldiers of different races.

In 1778, Washington said it was morally wrong to sell enslaved people publicly or to split up their families. After the war, he asked the British to return enslaved people who had escaped during the fighting. He said this was required by the peace treaty. However, the British did not return them. When Washington left his military role, he spoke about the challenges facing the new country. He did not directly mention slavery in his public speech.

Politically, Washington worried that the issue of slavery would divide the new nation. Because of this, he never spoke about it publicly. He signed laws that both protected slavery and laws that limited it.

Plans for Freedom and Washington's Will

In the mid-1790s, Washington privately thought about freeing the enslaved people he owned. But these plans did not work out. He couldn't get enough money to support them after they were freed. Also, his family would not agree to free the "dower slaves" (those from Martha's first husband's estate). He also didn't want to separate enslaved families.

By the time Washington died in 1799, there were 317 enslaved people at Mount Vernon. Washington personally owned 124 of them. Another 40 were rented. The rest belonged to the estate of Martha Washington's first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. These were meant for her grandchildren.

Washington's will was published widely after his death. It said that the enslaved people he owned would eventually be freed. He was one of the few Founding Fathers who owned slaves to make such a plan. His will stated that, except for his personal servant William Lee who was freed right away, his enslaved workers would serve his wife Martha until her death. Martha felt unsafe being surrounded by people whose freedom depended on her death. So, she decided to free them in 1801. However, neither George nor Martha Washington could legally free the "dower slaves." These enslaved people were inherited by Martha's grandchildren when she died in 1802.

Images for kids

-

Advertisement placed in the Pennsylvania Gazette after Oney Judge escaped from the President's House in 1796

-

The Washington Family, printed and engraved by Edward Savage in the 1790s. George and Martha are seated with their grandchildren, Washy and Nelly. The servant may be the enslaved Christopher Sheels.