History of slavery in Virginia facts for kids

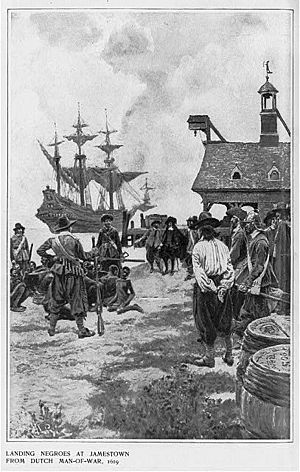

Slavery in Virginia started a long time ago. It began with Native Americans being captured and forced to work when English settlers first arrived in Virginia. Later, in 1619, about 20 Africans from a place called Angola were brought to Virginia on a ship named The White Lion. They were the first Africans forced into labor in the American colonies.

As the slave trade grew, enslaved people were usually forced to work on large farms called plantations. Their unpaid work made the plantation owners very rich. Virginia became a mix of different cultures: Native Americans, English, other Europeans, and West Africans. By the 1700s, plantation owners were the most powerful people in Virginia. There were also white people who managed the enslaved workers, and poorer white people who competed for jobs with free Black people.

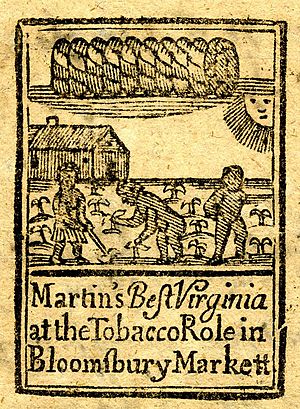

Tobacco was the main crop Virginia sold in the 1600s. But over time, selling and trading enslaved people became even more profitable than tobacco. Black people were seen as the most valuable "export" from Virginia. Enslaved Black women were often forced to have children to increase the number of enslaved people for sale.

In 1661, Virginia passed its first law allowing any free person to own slaves. More laws were passed to control enslaved Africans. By 1705, these laws were put together into Virginia's first slave code. Over the years, these laws took away more and more rights from enslaved people and protected the interests of slave owners.

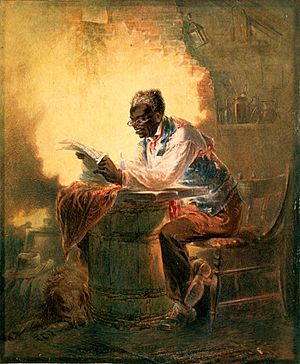

For over 200 years, enslaved people faced terrible things. This included physical abuse, being separated from their families, not having enough food, and being treated as less than human. Laws stopped them from learning to read or write. They needed permission to leave the plantation and could only leave for a few hours. Being sold away from family was one of the hardest things. To cope, they found ways to resist quietly and created work songs to help them get through tough days. They also created their own music styles, like Black Gospel music and sorrow songs.

In 2007, the Virginia General Assembly said they were "profoundly sorry" for Virginia's history of slavery.

Contents

Life in Colonial Virginia

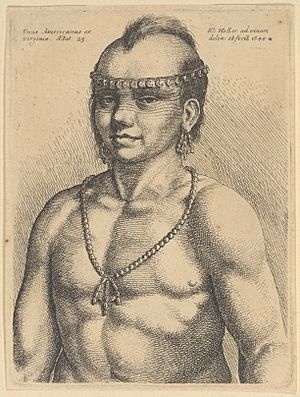

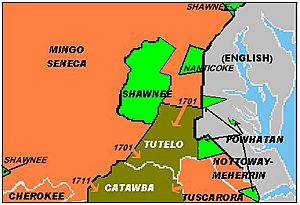

When English settlers arrived in the 1600s, there were about 30 Native American tribes in Virginia. They were loosely connected under a leader named Powhatan, who was the father of Pocahontas. Many colonists struggled to survive early on. Experts say that Native Americans and Africans helped the English by teaching them how to grow crops and manage animals. The English began enslaving Native Americans soon after they started Jamestown.

Africans were brought to Virginia by Dutch and English slave ships. Over the 1600s, the plantation system grew. Slavery slowly became a legal system, first through customs and then through laws. These laws limited what African Americans could do. For example, they couldn't meet in groups, own guns, or raise animals. They needed written permission to travel and could only leave plantations for four hours. Over time, even if Black people became Christians, they were still enslaved for life.

During the colonial period, most settlements were in the James River valley. There were not many stores, churches, or public schools. The valley was known for its huge tobacco plantations. On these plantations, tobacco growers treated enslaved people like property. Growing tobacco and later cotton needed a lot of land and many workers. Slavery made these crops profitable. As planters got richer, the gap between them and other white people grew. By 1860, there were 20,000 enslaved people in some northern Virginia counties.

Virginia plantation owners became very rich in the 1700s. They grew tobacco and used enslaved people for all the farm and house work. These wealthy planters were a new kind of aristocracy. But there were many more indentured servants, enslaved people, and poor white people than rich planters. An English officer visiting Virginia in 1779 said that plantation owners were educated. But he thought the white people who worked closely with enslaved people were often rude and focused on gambling.

Plantations were important for Virginia's economy. History books sometimes focus too much on the owners and their fancy houses. They often don't show the full story of enslaved people. Today, places like Thomas Jefferson's Monticello and George Washington's Mount Vernon are trying to show a more complete picture of colonial life, including slavery.

Slavery continued until the 13th Amendment ended it in 1865. Even after that, laws and practices still limited the rights of African Americans.

The Horrors of Slavery

Enslavement of Native Americans

After the first Africans arrived in 1619, slavery was found in all English colonies. Some Native Americans were also enslaved by the English. A few slaveholders owned both African and Native American slaves. These enslaved people worked in tobacco fields. Laws about Native American slavery changed over time. The number of enslaved Native Americans was highest in the late 1600s.

Virginia officially ended Native American slavery in 1705. This practice had already decreased because Native Americans could escape more easily into familiar lands. They also suffered from new diseases brought by the colonists. The Atlantic slave trade then brought many African captives to replace them as workers. Enslavement of Native Americans continued until the late 1700s. By the 1800s, they were either free or had joined African-American communities.

Native Americans were often captured during battles between English settlers and tribes. They fought because the English needed food and Native Americans were losing their land. In 1622, over 347 colonists were killed, and English settlements were burned. About 20 women were taken from a plantation and forced into "great slavery." To prevent escapes, captured Native Americans were often sent to British colonies in the West Indies to work as slaves.

First Africans in Virginia

In August 1619, about 20 Africans arrived at Point Comfort in Virginia. They were first traded for food and then sold in Jamestown as indentured servants. These Africans came from the Kingdom of Ndongo, which is now Angola. Angela, an enslaved woman from Ndongo, was one of the first enslaved Africans officially recorded in Virginia in 1619.

By 1620, there were 32 Africans and four Native Americans listed as "Others not Christians in the Service of the English." This number dropped by 1624, possibly due to war or illness. William Tucker, born in 1624, was the first person of African descent born in the Thirteen Colonies.

By 1625, Africans lived on plantations. Many were baptized as Christians and took Christian names. In 1628, another slave ship brought 100 people from Angola to Virginia, greatly increasing the number of Africans.

The Atlantic slave trade existed before Africans arrived in Virginia. Unlike white indentured servants, Black people could not negotiate their work contracts. They also couldn't easily defend their rights without proper papers. By the mid-1600s, some African Americans tried to go to court to claim they should only serve for a limited time. In most cases, their enslavers claimed they were bound for life. Most experts agree that "the vast majority" of Africans were treated as slaves from the start. It was very rare for Black people to have a legal contract for a limited time, but some did gain freedom.

Mary and Anthony Johnson were among the few African Americans who became free. They raised livestock and built a successful farm. In 1640, a Black servant named John Punch ran away. A Virginia court sentenced him to slavery for the rest of his life. Two white indentured servants who ran away with him only had four more years added to their service.

Unpaid Laborers

Household and farm work was done by indentured servants and enslaved people, including children. Indentured servants, usually from England, worked without pay for a set time. They traded their labor for passage to Virginia, room and board, and "freedom dues" at the end of their service. These dues could include land and supplies to help them start their own lives. In the 1600s, white indentured servants mostly worked Virginia's tobacco fields. By 1705, the economy relied on enslaved labor from Africa.

Enslaved people were generally held for their entire lives. Children born to enslaved women were also enslaved from birth. This was based on a law called partus sequitur ventrem. Some people argue that early records using the term "servant" for Black people meant they were indentured. But unlike indentured servants, enslaved people were taken against their will. When they were first sold for food, it was clear they were seen as property. Enslaved Black people were treated much more harshly than white servants. Whipping Black people, for example, was common.

Work and Daily Life

From Monday to Saturday, enslaved people had specific jobs. Most, including children, worked as farm hands. Others did household work like cooking, cleaning, and caring for white children. Some were trained as blacksmiths, carpenters, or coopers. On Sundays, they tended to their own livestock or gardens. It was also a day for family and worship.

Children worked too. By the late 1700s at Monticello, young Black children helped in the main house and looked after enslaved toddlers. When they turned ten, they were sent to work in the fields, the house, or to learn a skill like making nails or textiles. At 16, they might be forced into a trade. House work was less physically demanding than field work and offered chances to hear news. Life was harder for children in the fields, especially on large plantations. But the hardest thing was being separated from family members when they were sold. Some planters treated those they enslaved very cruelly.

Formalized Slavery Laws

A law making race-based slavery legal was passed in Virginia in 1661. It allowed any free person to own slaves. In 1662, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a law saying a child was born a slave if their mother was a slave. This meant "all children born in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother." This new law helped define the status of non-English people in Virginia. It also meant white fathers had no responsibility for their mixed-race children. If they owned them, they could make them work or sell them. This law also removed the rule against enslaving Christians. Slavery created a social class based on African descent, no matter a child's father. This rule became state law when Virginia became independent.

More laws about slavery were passed in the 1600s. In 1705, they were put into Virginia's first slave code, An act concerning Servants and Slaves. The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705 said that non-Christians, Black people, mixed-race people, or Native Americans would be classified as slaves. This meant they were treated like personal property. It also became illegal for white people to marry people of color. Slaveholders were allowed to punish enslaved people and would not be charged if a slave died from the punishment. The law listed punishments, including whipping and death, for small and large offenses. Enslaved people needed written permission, called passes, to leave their plantation.

Servants, who were different from slaves, had rights. They had rights to safety, food, and goods at the end of their service. They could also go to court to solve legal issues. Virginia had more offenses a Black person could commit than any other southern colony. Black people did not have fair legal processes to prove their innocence or appeal decisions.

Plantations and Farms

Virginia planters grew tobacco as their main crop to sell. Tobacco needed a lot of workers. Demand for it in England and Europe led to more African slaves being brought to the colony. Enslaved Black people replaced European servants in the 1600s because they were a more profitable source of labor. Slavery was supported by new laws and cultural changes. Virginia was where the first enslaved Black people arrived in English North America. From there, slavery spread to other colonies. Large plantations became common, changing Virginia's culture and economy. The plantation was a system of social and political unfairness, racial conflict, and control by the planter class.

Tobacco farming in eastern Virginia wore out the soil by 1800. Farmers then looked west for good land to grow crops. Corn and wheat were grown in the Piedmont plateau and the Shenandoah Valley. The number of slaves in the Shenandoah Valley was never as high as in eastern Virginia. This area was settled by German and Scotch-Irish people who didn't need or want slavery. This lack of competition with unpaid slave labor prevented the class divisions seen in the east. In western Virginia, the economy was based on raising animals and farming. It wasn't profitable to use slave labor there, except for a few tobacco farms, coal mines, or salt industries. Enslaved people were often rented out for coal and salt work, mostly from eastern Virginia, because the risk of death was high. Poor white people also worked in these industries. Enslaved people who were no longer needed in Virginia were rented out or sold to work in the cotton fields of the Deep South.

The interests of eastern and western Virginia were very different. The state of West Virginia was formed from the western counties of Virginia. It became a state in 1863. West Virginia chose not to join the Confederacy and was a free state during the American Civil War.

Culture and Resistance

African Americans created cultural traditions to help them cope with slavery. These traditions supported families and friends and helped them keep their human dignity. Music, folklore, cuisine, and religious practices by Black people influenced American culture. Africans brought their own language, music, dance, and food traditions to America. The first Africans from Angola may have brought some Christian practices they learned from Portuguese missionaries.

Enslaved African Americans taught their children and shared life lessons through stories from African folklore, parables, and proverbs. Animal characters in these stories often represented human traits. For example, tortoises might represent clever tricksters.

Religion and Music

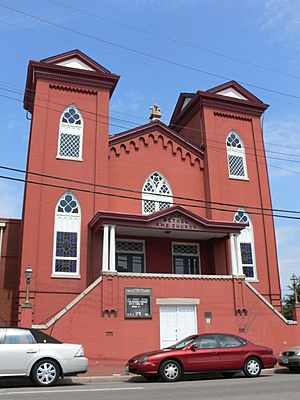

White people built churches where free Black people and enslaved people might worship, but in separate areas. Later, Black people were able to build their own churches.

Some enslaved people went to church, while others met secretly in the woods to worship. Religious practices, like music, call-and-response worship, and funeral customs, helped Black people keep their African traditions. They also helped them deal with the harshness of slavery.

Methodist and Baptist ministers preached about hope to enslaved Black people. Black people added shouts and sorrow songs to religious ceremonies. They created their own religious music with complex rhythms, foot-tapping, and unique singing styles. They sang communal songs called spirituals about freedom and salvation.

Music was very important in African American communities. Work songs and field hollers were used on plantations to coordinate tasks in the fields. Singing satirical songs was a way to resist the unfairness of slavery.

Food

The diet of enslaved people depended on the food they were given, mainly corn and pork. When hogs were butchered, the best cuts went to the master's house. The rest, like fatback, snouts, ears, neck bones, feet, and intestines (chitterlings), were given to the enslaved people. Cornbread was a common food, and corn was prepared in many ways, such as porridge, hominy, grits, and corn dodgers. Enslaved adults usually received about 9 liters of cornmeal and 1.5–2 kilos of pork per week. From these rations came soul food staples like cornbread, fried catfish, and neckbones.

Enslaved Africans added to their rations with cooked greens (collards, dandelion, kale) and sweet potatoes. Digs at slave quarters show their diet included squirrel, duck, rabbit, opossum, fish, berries, and nuts. Vegetables and grains included okra, turnips, beans, rice, and peas.

Enslaved people created their own cooking styles from the limited food they were given. They combined European, indigenous, and African cooking. They made gumbo, fricassee, fried foods, and soups from meat scraps and vegetables. This is how what is now called soul food began. These foods were cooked in their fireplaces.

Booker T. Washington, who was born enslaved on a Virginia tobacco plantation, described food shortages during the Civil War. He said it affected the owners more than the enslaved people. Owners were used to expensive foods, but enslaved people were already used to scarcity. He remembered eating boiled Indian corn meant for pigs if there was no breakfast. He also recalled his mother getting a chicken, likely from the plantation, and cooking it in the middle of the night.

Clothing

The clothes enslaved people wore in Virginia changed over time. It depended on when they lived, their jobs, and what their enslavers provided. They couldn't keep their traditional African clothing, though some women wore West African cloth head wraps.

In the 1700s, field workers likely wore uncomfortable, simple European-style clothes. These were made of cheap, rough fabrics like Negro cloth and osnaburg (from hemp and flax). Some people found these clothes so uncomfortable they tried to take them off when they could.

More comfortable fabrics, like jean cloth, were used in the 1800s. With more cotton production, ready-made clothes of mixed fabrics became common. If someone worked in the house or had a special job, they might have better quality clothing or uniforms. Girls wore simple gowns and then adult dresses after puberty. Boys' clothing changed as they grew, from gowns to short pants and then long pants. They were given shoes and sometimes hats. Clothes were usually given out twice a year. People could add personal touches like vegetable-dyed fabrics, sewn-on beads, or handmade necklaces. Some people planning to run away tried to get better clothes to blend in. They might steal clothes or buy them if they could earn money.

The Slave Trade

Transatlantic Slave Trade

The Atlantic slave trade began in the 1500s. Portuguese and Spanish ships carried enslaved people to South America and the West Indies. Virginia became part of this trade when the first Africans arrived in 1619. Enslaved people were sold for tobacco and hemp, which were sent to Europe. By 1724, about 1500 to 1600 enslaved people were brought to Virginia each year by merchants from Bristol and London.

The United States Congress made it illegal to import slaves from other countries in 1808. This made the business of selling slaves within the country grow even more.

Selling Enslaved People

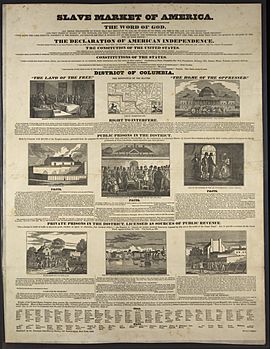

Richmond was a major center for selling enslaved people in Virginia. When enslaved people were sold, families and communities were often broken apart. People were commonly separated from their spouses and children, sometimes forever. They were taken from plantations and put into jails or slave pens by slave traders. They might stay there for weeks and faced upsetting physical inspections. At auctions, they could be sold to another trader or directly to work on plantations in the Lower South.

The price for enslaved people changed based on age, gender, and the time period. Women were worth about 80 or 90 percent of what men would bring. Children were worth about half the value of a strong male field worker. In the late 1830s, the highest price for an enslaved person was $1,250, due to a boom in the cotton industry. Prices dropped in the 1840s but recovered in the late 1850s, reaching about $1,450.

Alexandria was another important slave trade center. It was part of the land given by Virginia to the U.S. government to create Washington D.C. Later, this land was given back to Virginia. Once it was part of Virginia again, Alexandria's slave trade business was safe. One main reason the land was returned was that ending slavery in Washington D.C. was a goal of abolitionists. Slave owners and traders strongly opposed this, wanting to protect their businesses. So they wanted Alexandria to be in slave-holding territory.

Controlling and Resisting Slavery

Slaveholders were always worried that enslaved people might run away or revolt. They used many ways to control them. One tactic was to stop African Americans from learning to read and write. They limited chances for groups of people to meet and stopped them from leaving the plantation. Enslaved people who tried to escape and were caught were punished publicly. Punishments included execution and physical harm. White Virginians who helped Black people break the rules were also punished. Other control methods included giving small rewards, using religion, the legal system, and scaring people.

Enslaved people found various ways to resist. The most effective way was by keeping their own culture alive through religion, stories, and music. Other ways included working slowly, stealing food, or breaking the slaveholder's property. Even though the risks were high, some people still tried to escape when they could.

Revolts and Calls for Change

In the 1800s, there were three major attempted slave revolts in Virginia. These were Gabriel's Rebellion in 1800, Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831, and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, led by a white abolitionist named John Brown. After Nat Turner's rebellion, thousands of Virginians asked the state government to end slavery. Richmond newspapers strongly argued for abolition. Historians say this was the most public and focused discussion about slavery and freedom in Virginia or any other southern state. About a third of these requests also asked for all free Black people to be forced to leave Virginia and go to Liberia. By 1859, free Black people were not allowed to enter Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson's grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, led the group in the Virginia government that wanted to end slavery. Their proposed law would have freed all children born to enslaved parents after July 4, 1840. But it failed by one vote.

Gaining Freedom

Opportunities for most enslaved African Americans to become free were very rare. Some were freed by their owners to keep a promise, give a reward, or, before the 1700s, to finish a service agreement. A few were bought by Quakers and other religious groups just to free them. This practice was soon banned in the southern states. Many ran away to free areas, and some of these "fugitives" managed to avoid being caught.

Many enslaved people gained freedom before the American Civil War. Some were freed by their slaveholder through a process called manumission. Rules for manumission began in 1692. Virginia required a person to pay for the freed slave to be transported out of the colony. A 1723 law said slaves could not "be set free upon any pretense whatsoever, except for some meritorious services."

The new government of Virginia changed these laws in 1782. They declared freedom for slaves who had fought for the colonies during the American Revolutionary War. The 1782 laws also allowed masters to free their slaves on their own. Before this, freeing a slave needed permission from the state government, which was very hard to get. After 1800, it was rare, but some people could buy their own freedom. As the abolition movement grew, more people were freed.

Many free Black people were very skilled. Some were tailors, hair stylists, musicians, cooks, and craftspeople. Others were educators, writers, business people, and farmers. Famous freed people include Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, Sarah Allen, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman. Thomas L. Jennings invented a dry-cleaning method, and Henry Blair patented a seed planter.

Free Black people were generally older than the enslaved population. This was partly because slaveholders often freed Black people when they became disabled or had health problems due to age. If they wanted to buy their freedom, enslaved people had to save money for the asking price. Children of white enslavers were more likely to be treated better and gain their freedom. Skilled free Black people of mixed race made up a large part of the freed slaves.

Indentured Servitude

Indentured servitude was a contract between English people and their masters. It set how many years they would work in exchange for passage to Virginia and their living costs. One rule was that they couldn't marry while in service. Early servants received a share of profits from the Virginia Company of London. Later, to attract more workers, English indentured servants were promised land after their contract ended. Servants and masters could take each other to court if the contract terms weren't met or for wrongs like abuse.

From the start, Africans were not treated the same as English indentured servants. White indentured servants were listed in early records with their arrival date, last names, and marital status. Black people were often listed only by their first names, if at all. Records show seven cases where Africans or African Americans claimed they had served a limited time and earned freedom, like indentured servants. But their masters claimed they were enslaved for life. Six of these cases failed, showing that Virginia courts saw Africans and African Americans as enslaved for life.

Anthony Johnson was an African who became free early on. He later owned land and had a contract with John Casor as an indentured servant. Casor worked his agreed time and then another seven years. They went to court, and the judge ruled that Casor would be Johnson's slave for the rest of his life. Philip Cowen had worked his agreed years as a servant and expected to be freed. But like other Black people, he was forced to sign a document extending his service. He filed a lawsuit in 1675 and won. He was given new clothes and three barrels of corn, as promised.

In an unusual court case, John Graweere, an indentured servant, asked to buy his son. The boy was born to an enslaved woman. Graweere wanted to raise him as a Christian. The court ruled in his favor in 1641, and he was able to free his son.

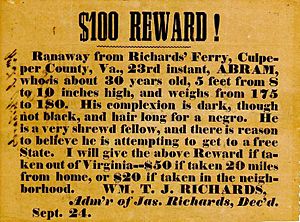

Running Away

Another way to gain freedom was to run away, becoming a fugitive slave. Both indentured servants and enslaved people ran away for different reasons. They might be looking for separated family members or escaping cruel masters and hard work.

Enslaved people from Virginia escaped by water and land to free states in the North. Some were helped by people along the Underground Railroad, which included both white and Black helpers. Even with many controls, many still ran away. They had to cross wide rivers or the Chesapeake Bay, which could be dangerous. People often headed for Maryland and places further north like New York and New England. They might also meet unfriendly Native Americans.

In 1849, Henry "Box" Brown escaped slavery in Virginia. He arranged to be shipped by express mail in a crate to Philadelphia, arriving in just over 24 hours.

From 1736 to 1803, at least 4,260 notices for runaway slaves were published in Virginia. People who helped catch runaways received a cash reward. Advertisements were also placed in newspapers when fugitives were caught. If enslaved people ran away many times and were returned, they might be branded, chained, or have their hair cut in a way that made them easy to identify.

Sometimes, Black and white people ran away together, with very different results. In 1643, the Virginia General Assembly passed laws about runaway servants and slaves. In 1660, the Assembly said that if any English servant ran away with Black people who couldn't pay back their time, the English servant would have to serve for the time the Black people were gone. The law of 1705 allowed for harsh punishment of slaves, even killing them. There were no consequences for excessive punishment or killing slaves after this law passed.

Buying Freedom

Another way to freedom was to buy it by saving money. In 1839, over 40 percent of free Black people in Cincinnati, Ohio had paid for their freedom. Moses Grandy, born in North Carolina but who worked in Virginia, bought his freedom twice. If a formerly enslaved man wanted to buy his wife and children's freedom, he had to convince the slaveholder to allow it, which could take years. If they agreed, a price was set. The deal could be broken if the slaveholder died before the family was freed.

Mary Hemings, an enslaved woman from Thomas Jefferson's Monticello plantation, and two of her children, were bought by her husband, Thomas Bell. She couldn't buy her two oldest children. One of them, Joseph Fossett, was later freed by Thomas Jefferson's will. Joseph and his brother-in-law bought the freedom of Joseph's wife, Edith Hern Fossett, and their children. Also from Monticello, Israel Jefferson bought his freedom with his wife's help. Peter Hemmings was bought by a family member and then freed. Mary Colbert's freedom was also obtained by family members.

Freedom Suits

In 1658, Elizabeth Key was the first woman of African descent to bring a freedom suit in the Virginia colony. She wanted to be recognized as a free woman of color, not as a Black slave. Her father was an Englishman and a member of the House of Burgesses. He recognized her, had her baptized as a Christian, and arranged for her care under a contract before he died. Before her guardian returned to England, he sold Key's contract to another man. This man held Key beyond the contract term. When he died, his estate classified Key and her child as Black slaves. Key sued for her freedom and her son's freedom. She based her case on their English ancestry, her Christian status, and the contract. She won her case.

Manumission

Some enslaved people were freed by their enslavers. Sometimes, people were freed because their enslavers liked them. Other times, it was because the enslaved person was no longer useful. In some cases, mixed-race children of white slaveholders were freed.

White Virginians found freed Black people to be a "great inconvenience." They were suspicious of their ability to influence enslaved people and accused them of crimes. So, laws were passed to make things harder for Black people and their enslavers. In 1691, a law required freed people to leave the colony. It also required former slaveholders to pay for their travel. In 1723, a law made it harder to free slaves:

No negro, mullatto, or Indian slaves, shall be set free, upon any pretence whatsoever, except for some meritorious services, to be adjudged and allowed by the governor and council, for the time being, and a licence thereupon first had and obtained.

Those who were freed could be sold back into slavery if enough people complained about them. In the early years, "meritorious service" meant telling authorities about rebellion plans. Later, it meant being faithful or having excellent character.

After the American Revolutionary War, many slaveholders in Virginia freed some or all of their slaves. This was inspired by the Revolution and religious preachers. In 1782, it became easier to free enslaved Black people. But if they were over 45, the former slaveholder might have to provide them an income if they couldn't work. In 1806, freed slaves had to leave the state after one year of freedom.

The number of free Black people in Virginia grew from 1,800 in 1782 to 12,766 in 1790. By 1810, it was 30,570. This meant free Black people went from less than one percent to 7.2 percent of the total Black population. One planter, Robert Carter III, freed over 450 slaves starting in 1791, more than any other planter. George Washington freed all his slaves when he died.

Life After Freedom

Where Freed People Lived

Most free people of color lived in the American South, but freed people lived throughout the United States. In 1860, the U.S. census showed that 250,787 lived in the South and 225,961 lived in other parts of the country. In the North, free Black people made up 100 percent of the Black population. Large groups of free Black people lived in Philadelphia, Virginia, and Maryland.

In the South, free Black people were only about six percent of the Black population. Generally, women were more likely to stay in Virginia, and men were more likely to go North. Those who stayed often moved to cities where work was easier to find. Many freed people and runaways lived in the Great Dismal Swamp maroons of Virginia. Those in western Virginia became West Virginians in 1863. Even during the American Civil War, Black Virginians were more likely to stay in the state.

Education for Freed People

African Americans started schools for freed people in Virginia soon after the American Civil War began (1861–1865). These schools were taught by white and Black teachers. Black teachers taught longer than white teachers during Reconstruction.

The federal government provided supplies to build schools through the Freedmen's Bureau. They also transported teachers to Virginia. The American Missionary Association and other groups sent teachers, books, and supplies. Evidence suggests that Black education in Virginia was mainly due to the freed people's own efforts. It was temporarily supported by help from the North and federal aid.

Religion for Freed People

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, which grew from the Free African Society, was founded by Richard Allen in Philadelphia. It was very important to communities of free African Americans. It spread to Charleston, South Carolina and other Southern areas, even though laws tried to stop Black people from preaching. The church was often treated badly by white people, and members were arrested in large numbers.

Challenges for Freed People

Freedom had its difficulties. There were laws, especially in the Upper South, that created problems for free Black people. Lawmakers wanted to keep track of free Black people by registering them, sending them away, or putting them in jail. They made it harder for Black people to testify in court and to vote.

Anthony Johnson was an African who became free soon after 1635. He settled on land and later bought African indentured servants as workers. Even though Anthony Johnson was a free man, when he died in 1670, his farm was given to a white colonist, not to Johnson's children. A judge had ruled that he was "not a citizen of the colony" because he was Black.

The Civil War and Freedom

The American Revolutionary War of 1776 and the Constitution of 1787 left open questions about who should rule. Americans were proud to say America was "the land of liberty" in the early 1800s. However, by the 1850s, the United States had become the largest slaveholding country in the world. From 1789 to 1861, two-thirds of the country's presidents, almost three-fifths of its Supreme Court justices, and two-thirds of its House Speakers were slaveholders. There was growing tension between the Southern plantation society, which relied on slave labor, and the "diversified, industrializing, free-labor capitalist society" in the North. Richmond, Virginia, became the capital of the Confederacy.

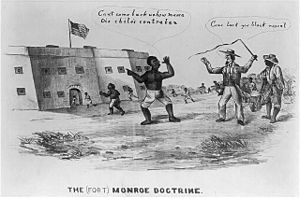

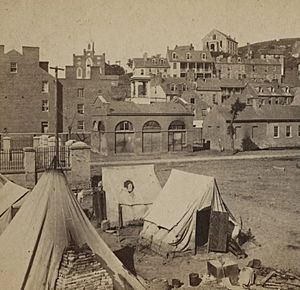

In June 1861, enslaved people traveled with their families to Union army camps, like Fort Monroe. They thought they would be free there. However, they ended up working very hard in difficult, unhealthy conditions. They didn't have an enslaver, but the military treated them similarly.

During the American Civil War, free Black people worked as cooks, teamsters, and laborers. They also worked as spies and scouts for the United States military. Starting in 1863, about 180,000 African Americans joined the United States Colored Troops and fought for the Union Army. The Confederacy had no similar Black troops. More white soldiers began to see the need to end slavery and unite the country. A soldier named Constant Hanks wrote in 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation: "Thank God... the contest is now between Slavery & Freedom, & every honest man knows what he is fighting for."

Booker T. Washington, who was born enslaved in Franklin County, Virginia, later described food shortages during the Civil War. He said they affected the owners much more than the enslaved people. Owners were used to expensive items before the war, but the lack of these items had little impact on the enslaved people.

Thousands of enslaved people went to Harpers Ferry, Virginia, a town behind Union lines, for protection. These individuals were called contrabands. Their protection was only as safe as the Union lines. When the Confederates took back Harpers Ferry in 1862, hundreds of contrabands were captured.

The End of Slavery in Virginia

The first big step to ending slavery in Virginia was President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863. However, it only applied to areas controlled by the Union Army. Charlottesville celebrated the arrival of Union troops on March 3, 1865, which brought freedom to everyone enslaved there. This is now a holiday called Liberation and Freedom Day. The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which became law on December 18, 1865, made slavery illegal everywhere in the country.

Remembering History

Learning about the history of slavery in the United States sometimes hides the truth of the terrible physical and mental cruelty enslaved people faced. Schoolbooks can often just touch the surface of slavery. Historians and educators say we need to change how slavery is taught. They want to acknowledge how wrong ideas and downplaying the past still affect the lives of African Americans today. This includes fewer opportunities, a higher chance of being in prison, and being victims of hate crimes.

In 2007, the Virginia General Assembly formally said they were "profoundly sorry" and acknowledged the "terrible wrongs" done to African Americans. Part of their statement says:

The General Assembly hereby expresses its profound regret for the Commonwealth's role in sanctioning the immoral institution of human slavery, in the historic wrongs visited upon native peoples, and in all other forms of discrimination and injustice that have been rooted in racial and cultural bias and misunderstanding...

—Virginia General Assembly

This statement was made in May 2007, to mark 400 years since the first Virginian settlers arrived at Jamestown.

The place where the First Africans landed is now Fort Monroe. In 2011, President Barack Obama read a statement saying: "The first enslaved Africans in England's colonies in America were brought to this peninsula on a ship flying the Dutch flag in 1619, beginning a long ignoble period of slavery in the colonies and, later, this Nation." The fort was made a National monument.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |