Great Dismal Swamp maroons facts for kids

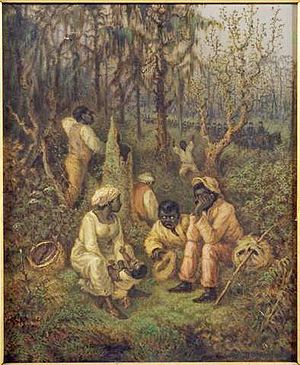

Fugitive Slaves in the Dismal Swamp, Virginia, by David Edward Cronin, 1888.

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Extinct as ethnic group | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Great Dismal Swamp | |

| Languages | |

| English and or English-based creole | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity and or African diaspora religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| African-Americans, Gullah, Black Seminoles, maroons |

The Great Dismal Swamp maroons were people who found freedom by living in the Great Dismal Swamp. This large swamp is located in parts of Virginia and North Carolina. These brave people had escaped from slavery.

Life in the swamp was very tough. But thousands of people lived there between the early 1700s and the 1860s. The writer Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote about these maroon communities in her 1856 book, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp. Modern research on these settlements began in 2002. This important work was led by Dan Sayers from American University.

Contents

Life in the Great Dismal Swamp

The first enslaved Africans arrived in the British colonies in Virginia in 1619. They came on a ship called the White Lion. These people were from present-day Angola. At first, they were treated like indentured servants. This meant they could gain freedom after a certain time. Some also bought their freedom or became free by converting to Christianity.

Later, laws were passed that made slavery legal. Many enslaved people were forced to work in the Great Dismal Swamp. They helped drain the land and cut down trees. People who escaped slavery and lived freely were called maroons or outliers.

What is a Maroon Community?

Maroon communities were hidden settlements where self-liberated Africans lived. These communities existed in many Southern states. Swamp-based maroon groups were found in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina. In the Upper South, maroon communities were mostly in Virginia. The Great Dismal Swamp was one of the largest.

The word maroon might come from Spanish, Arawak, or Taino words. It likely shares roots with the word Seminole. Both probably come from the Spanish word cimarrón. This word means "wild" or "untamed." It was often used for people who escaped slavery.

Living in the Swamp

Maroon communities began forming in the Great Dismal Swamp in the early 1700s. Most settled on "mesic islands." These were higher, dry areas within the swamp. Both people who bought their freedom and those who escaped lived there. Some also used the swamp as a path on the Underground Railroad. This was a secret network to help people escape to freedom further north.

People in the swamp lived in tough conditions. They faced dense plants, insects, snakes, and bears. But these dangers also made the swamp a perfect hiding spot. Not only formerly enslaved people lived there. Free Africans, enslaved people working on canals, Native Americans, and even some outcast white people found refuge there.

Some maroons were born in the swamp and lived there their whole lives. They often traded with enslaved people and poor white neighbors. They exchanged goods for food, clothes, and money. Some maroons also took things from nearby farms or boats.

How Many People Lived There?

Historians believe thousands of people lived in the Great Dismal Swamp. This includes Native Americans, maroons, and enslaved workers. One study in 2011 suggested thousands lived there between the 1600s and 1860s. By the 1800s, "several thousand" people were living there. It is thought to be one of the largest maroon communities in the United States.

Local white people were often worried about these free communities. In 1823, a group with dogs tried to remove the maroons. But most people escaped. In 1847, North Carolina passed a law to catch maroons in the swamp. However, unlike other maroon groups, those in the Great Dismal Swamp often avoided capture. Their homes were rarely found.

Native American Connections

Native American tribes also lived in or near the swamp. The Chesapeake, Nansemonds, Recharians, and Merrians were connected to the swamp in the 1600s. Evidence shows the area was used for hunting as far back as 5,000 years ago. Native American communities were already there when maroons arrived.

Because leaving the swamp was risky, people used what they found there. They even reused old tools left by Native Americans. Few items have been found from maroon settlements. This makes it hard for historians to learn about their daily lives. The swamp's acidic water may have dissolved any bones left behind.

The Dismal Swamp Canal

The Dismal Swamp Canal was built between 1793 and 1805. Some maroon communities were set up near this canal. These groups had more contact with the outside world. Some maroons even took jobs on the canal. As the canal brought more outsiders, some people eventually left the swamp.

During the American Civil War, the United States Colored Troops went into the swamp. They helped free the people living there. Many maroons then joined the Union Army. Most of the maroons who stayed in the swamp left after the Civil War ended.

Why Maroon Communities Ended

The maroon communities in the Great Dismal Swamp were built on strength and survival. They chose hard-to-reach areas to live freely. They used only natural resources from the swamp to build homes and tools. This is why few traces of their settlements remain today. These communities were very good at adapting to the swamp's changing environment.

However, these communities eventually broke up for several reasons:

- The Civil War: Many people left to fight for the Union Army.

- Abolition of Slavery: After slavery ended, many left to find family or move north.

- Swamp Development: Companies began to develop the swamp. Land was drained for farms and cleared for roads. Railroads were built through the swamp by 1836. An interstate highway was also built around the area.

- Tourism: The swamp became more popular for visitors and businesses. Many free and formerly enslaved people left as tourism and commerce took over.

Even though these communities ended, they show the power of black resistance and self-reliance. Researchers say these communities are often overlooked. This is partly because they left few artifacts for study.

Daniel Sayers, a researcher from American University, says: "There were hardships and deprivations, for sure... But no overseer was going to whip them here. No one was going to work them in a cotton field from sunup to sundown, or sell their spouses and children. They were free. They had emancipated themselves."

Location of the Great Dismal Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp is a large area. It stretches across southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. It lies between the James River near Norfolk, Virginia, and the Albemarle Sound near Edenton, North Carolina.

The swamp was once huge, covering over 1 million acres. But human activity has destroyed about 90% of it. Today, the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge is about 112,000 acres. The swamp also includes Lake Drummond, which is about 3,100 acres. The Dismal Swamp Act of 1974 now protects the swamp. This act created the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. North Carolina also declared the Dismal Swamp State Park to protect the area.

Researching the Maroons

The Great Dismal Swamp Landscape Study started in 2002. It is led by Dan Sayers, an archaeologist from American University. In 2003, he began the first dig in the swamp. In 2009, he started an annual research program. This program is called the Great Dismal Swamp Archaeology Field School. It works with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

This research looks at how colonialism, slavery, and development affected the swamp. It focuses on the self-sufficient maroon settlements deep inside the swamp. It also studies how Native Americans lived before Europeans arrived. Before Sayers' work, no field research had been done on the Great Dismal Swamp maroons.

Even today, parts of the swamp are very hard to reach. A research group in 2003 gave up because they kept getting lost. Sites deep in the swamp still need a guide to find them. In 2010, the National Endowment for the Humanities gave $200,000 to this project.

In 2011, the National Park Service opened a permanent exhibit. It honors those who lived in the swamp before the Civil War. Sayers says: "These groups are very inspirational. As details unfold, we are increasingly able to show how people have the ability, as individuals and communities, to take control of their lives, even under oppressive conditions."

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |