Henry Box Brown facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Box Brown

|

|

|---|---|

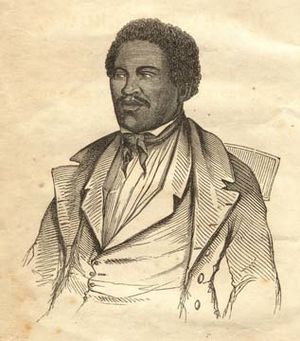

The Narrative of Henry Box Brown (1849)

|

|

| Born |

Henry Brown

c. 1815 |

| Died | June 15, 1897 (aged 81–82) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Abolitionist |

| Spouse(s) | First wife – Nancy (sold by slaveowner) Second wife – Jane Floyd |

Henry Box Brown (born around 1815 – died June 15, 1897) was an amazing man from Virginia. He was born into slavery, which meant he was owned by someone else and not free. When he was 33 years old, in 1849, he found a very clever way to escape. He mailed himself in a wooden box to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he would be free. He sent himself to people called abolitionists, who were against slavery.

After his escape, Henry Box Brown became a well-known speaker in the United States. He spoke out against slavery. But a new law, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, made it easier for slave owners to catch escaped slaves. Because he was famous, Henry felt he was in danger. So, he moved to England and lived there for 25 years. In England, he continued to fight against slavery. He also became a magician and a showman.

Henry married an English woman named Jane Floyd and started a new family. His first wife, Nancy, was still enslaved in America. In 1875, Henry returned to the United States with his English family. He kept working as an entertainer, performing magic and giving talks until at least 1889. He spent the last years of his life in Toronto, Canada, where he passed away in 1897.

Contents

Early Life and Slavery

Henry Brown was born into slavery around 1815 or 1816. This happened on a large farm called Hermitage in Louisa County, Virginia. Henry remembered his parents fondly. He said his mother taught him about Christian values. He also had at least two siblings, a brother and a sister.

When Henry was about 15, he was sent to work in a tobacco factory in Richmond. In his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself, he described his owner. He said his owner was "uncommonly kind" for a slaveholder. But even kind owners still held people in slavery.

A Daring Escape to Freedom

Henry Brown was married to another enslaved person named Nancy. Their marriage was not legal under the laws of the time. They had three children. These children were also born into slavery because of a rule called partus sequitur ventrem. This rule meant that if a mother was enslaved, her children were also enslaved.

Henry's owner rented him out to work in a tobacco factory in Richmond, Virginia. Henry rented a house where he lived with Nancy and their children. He even paid Nancy's owner money to stop him from selling his family. But the owner broke his promise. He sold Nancy, who was pregnant, and their three children to a different slave owner. This was a terrible loss for Henry.

After this heartbreak, Henry decided he had to escape. He got help from two men: James C. A. Smith, who was a free Black man, and Samuel A. Smith, a white shoemaker. Henry came up with a bold plan. He would ship himself in a box to a free state. He chose the Adams Express Company because they were known for being private and efficient. Henry paid Samuel Smith $86, which was a lot of money back then. He had saved $166 in total.

Samuel Smith went to Philadelphia to talk to members of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. These were people who worked to end slavery. He met with a minister named James Miller McKim, William Still, and Cyrus Burleigh. They helped him plan the escape. They decided to send the box to Passmore Williamson, a Quaker merchant who helped escaped slaves.

To get the day off work for his escape, Henry injured his hand. The box he was shipped in was about 3 feet long, 2.67 feet wide, and 2 feet tall. It had "dry goods" written on it. Inside, it was lined with a coarse cloth, and Henry had only a little water and a few biscuits. There was just one small hole for air. Henry later wrote that the risk was worth it. He said that the hope of freedom was like "an anchor to the soul."

The journey began on March 29, 1849, and lasted 27 hours. The box traveled by wagon, train, steamboat, and ferry. Even though the box said "handle with care" and "this side up," it was sometimes placed upside-down or handled roughly. Henry stayed still and quiet, and no one found him.

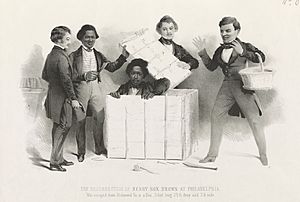

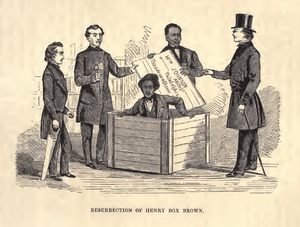

On March 30, 1849, the box arrived in Philadelphia. Passmore Williamson, James Miller McKim, William Still, and others from the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee were there to receive it. When Henry was finally let out of the box, one person remembered his first words: "How do you do, gentlemen?" He then sang a psalm from the Bible to celebrate his freedom.

Henry's escape showed how powerful the mail system was. It connected the East Coast using different types of transportation. The Adams Express Company, a private mail service, was popular with abolitionists. They promised never to look inside the boxes they carried.

Life as a Free Man

Henry became a famous speaker for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. He even met Frederick Douglass, another well-known abolitionist. At an anti-slavery meeting in Boston in May 1849, he was given the nickname "Box." From then on, he was known as Henry Box Brown.

He wrote two versions of his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown. The first was published in Boston in 1849. The second was published in Manchester, England, in 1851, after he moved there. Henry also created a moving panorama, which was like a long painting that unrolled to tell a story. He used it to share his anti-slavery message.

Frederick Douglass wished that Henry had not shared the details of his escape. This was because others might have tried to use the same method, which could put them in danger. In fact, Samuel Smith tried to help other enslaved people escape from Richmond in 1849, but they were caught.

Henry spoke out strongly against slavery. In his book, he suggested ways to end slavery. He thought enslaved people should get the right to vote, and a new president should be elected. He also believed the North should speak out against the South's support of slavery.

After the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed, Henry moved to England for his safety. He was a public figure, and the new law made it very risky for him to stay in the U.S. He toured Britain with his anti-slavery panorama for ten years, performing hundreds of times a year. After the American Civil War began, he left the anti-slavery circuit. He then performed as a magician and showman for 25 years, until 1875. He used stage names like "Prof. H. Box Brown" and the "African Prince."

In 1855, while in England, Henry married Jane Floyd. She was a white woman from Cornwall. They started a new family together. In 1875, he returned to the U.S. with his new family. They performed a magic act together. Later, they were known as the Brown Family Jubilee Singers.

Later Years and Death

Henry Box Brown continued to perform into the early 1890s. The last known performance by Henry was with his daughter Annie and wife Jane in Brantford, Ontario, Canada, on February 26, 1889.

Henry Box Brown passed away in Toronto, Canada, on June 15, 1897.

Henry Box Brown's Legacy

Henry Box Brown's story has inspired many people.

- The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia is a famous lithograph by Samuel Rowse. It shows Henry coming out of the box into freedom. This image helped raise money for Henry's anti-slavery panorama.

- There is a monument to Henry "Box" Brown along the Canal Walk in downtown Richmond, Virginia. It is a metal copy of the box he escaped in.

- A historical marker in Louisa County, Virginia, honors Henry Box Brown and his escape.

- Many books and plays have been created about Henry's life.

- The Unboxing of Henry Brown (2003) is a biography by Jeffrey Ruggles.

- Ellen Levine wrote a children's picture book called Henry's Freedom Box (2007). It won the Caldecott Honor.

- Tony Kushner wrote a play called Henry Box Brown, which first showed in 2010.

- Doug Peterson wrote a historical novel based on Henry Brown called The Disappearing Man (2011).

- Sally M. Parker wrote a children's book, Freedom Song: The Story of Henry "Box" Brown (2012).

- Box Brown (2012) is a film about him by director Rob Underhill.

- Playwright Mike Wiley wrote a one-man show about Henry Box Brown called One Noble Journey.

- In 2014, Joel Christian Gill published a comic novel, Strange Fruit, Volume I: Uncelebrated Narratives from Black History, which included Brown's story.

- Henry Box Brown's story is mentioned in the song "Diasporal Histories" by Professor A.L.I.

- He is also featured in the poetry collection Olio (2016) by Tyehimba Jess.

- His story is part of the 2019 Kevin Hart Netflix Original “Kevin Hart’s Guide To Black History”.

- Henry Box Brown was played by Ade Otukoya in an episode of the TV series Dickinson.

A Song of Freedom

When Henry Box Brown was released from the box, he sang a song of thanks. It was inspired by Psalm 40 from the Bible. Here are some lines from his song:

I waited patiently for the Lord

And he, in kindness to me, heard my calling

And he hath put a new song into my mouth

Even thanksgiving — even thanksgiving

Unto our God!

Blessed-blessed is the man

That has set his hope, his hope in the Lord!

O Lord! my God! great, great is the wondrous work

Which thou hast done!

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |