Tobacco in the American colonies facts for kids

Tobacco farming and selling were a huge part of the American colonies' economy. During the American Civil War, tobacco was different from other important crops. It had its own farming needs, trade rules, and relied heavily on enslaved people. Many important American leaders, like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, owned tobacco farms. They faced serious money problems because of debts to British tobacco sellers just before the American Revolution.

Contents

Starting Tobacco Farms

John Rolfe, a settler from Jamestown, was the first European colonist to grow tobacco in America. He came to Virginia with tobacco seeds he got during a trip to Trinidad. In 1612, he harvested his first crop to sell in Europe. Rolfe's tobacco business quickly became a huge success for American exports.

The Chesapeake Tobacco System

As people in England used more tobacco, it became a major economic power in the American colonies. This was especially true in the tidewater region around the Chesapeake Bay. Huge farms were built along Virginia's rivers. Special ways of growing and selling this cash crop (a crop grown for profit) developed.

In 1713, a law called the Tobacco Act was passed. It said that all tobacco meant for export or for use as money had to be checked. In 1730, the Virginia House of Burgesses made the Tobacco Inspection Act of 1730. This law made sure tobacco quality was good. Inspectors checked tobacco at 40 special places. This system also involved bringing enslaved African people to grow the crops. Farmers would fill large barrels called hogsheads with tobacco. They then sent these barrels to special warehouses for inspection.

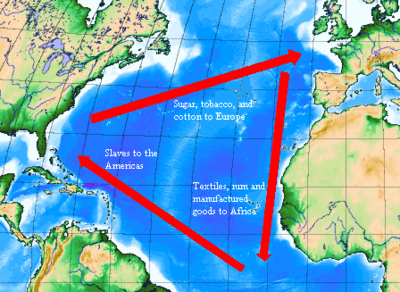

The tobacco economy in the colonies was part of a cycle. There was a demand for tobacco leaves, a demand for enslaved workers, and global trade. This led to the Chesapeake Consignment System and the rise of "Tobacco Lords". American tobacco farmers would send their crops to merchants in London to be sold. To do this, they had to borrow money from London lenders for farm costs. In return, they promised to deliver and sell their tobacco. More deals were made with sellers in Charleston or New Orleans to ship the tobacco to London. The farmers would then pay back their loans with the money from their sales.

As Europeans wanted more tobacco, American farmers made their farms bigger and grew more. This meant they needed more hours of work, so farmers bought more enslaved people. They also had to get bigger loans from London. This put more pressure on them to grow a good crop. It also made them more likely to lose money if natural disasters happened.

Enslaved Labor on Tobacco Farms

Growth of Enslaved Population in the 1700s

The number of enslaved people in the Chesapeake area grew a lot in the 1700s. This was because there was a high demand for cheap tobacco labor. Also, fewer people from England were willing to come work as servants. During this century, it's thought that the enslaved African population in the Chesapeake went from 100,000 to 1 million. They made up most of the workforce and about 40% of the total population. After 1775, new enslaved people were not brought to the Chesapeake. However, the enslaved population kept growing until 1790. This was because masters forced them to have many children to increase the workforce.

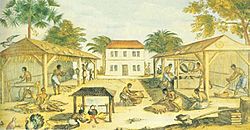

Before this big increase in enslaved people, Chesapeake tobacco farms were different. White farmers often worked alongside the enslaved people. The differences between races were not as strict. As more enslaved people were brought in, strong racial differences appeared. Work groups made up only of Black enslaved people, watched over by white farmers, became common. Unwritten rules based on race became normal in society.

Many farmers saw a chance to make money from tobacco. But they also faced money worries and stress because of tough competition and falling prices. Some historians believe these worries were taken out on the enslaved workers. This made the already difficult racial relationships even worse. Farmers pushed enslaved people to work as hard as possible to make sure the crop was good. Enslaved people knew that the crop's quality depended on their effort. They sometimes "foot dragged," which meant they would slowly work together to protest the farmers' extreme demands. Farmers often said this slow work was just how enslaved people were. William Strickland, a rich colonial tobacco farmer, said:

- "Nothing can be more lazy than a slave; his unwilling work is seen in every step he takes; he doesn't move if he can avoid it; if the overseer isn't watching him, he sleeps… everything is lazy; all movement is clearly forced."

Sometimes, arguments between enslaved people and farmers got so bad that work stopped. When this happened, masters often punished enslaved people with physical violence until they started working again.

Differences Between Chesapeake and Deep South Farms

In the Chesapeake area and North Carolina, tobacco was a very large part of all the crops grown. In the Deep South (mainly Georgia and South Carolina), cotton and rice farms were most common. The different places and societies in these two regions led to different ways of life for enslaved people.

The Chesapeake had fewer big cities compared to the South. Instead, many markets were set up along rivers. This helped smaller tobacco farms because it kept the cost of moving tobacco to market low. In the South, all business went through a few big markets. This favored large farms that could afford the higher shipping costs. Differences in farm size also depended on what was needed for tobacco farming versus cotton and rice. Cotton and rice were cash crops grown to get the largest amount possible. After a certain point, adding more work didn't improve the quality of the harvest. Tobacco, however, was seen as more of an art. There was always a chance to make the crop better and higher quality. So, the most profitable cotton and rice farms were large and worked like factories. Tobacco profits depended on skilled, careful, and efficient enslaved workers.

Because less training was needed for cotton and rice, families of enslaved people on these farms often stayed together. They were bought and sold as whole families. Individual enslaved people generally lived shorter lives. This was because their skills were less specialized, and workers could be easily replaced if they died. Cotton and rice farm owners used a method called "tasking." Each enslaved person would get about half an acre of land to work on their own with little watching. The amount of crop from each person's plot showed how well they worked.

In contrast, tobacco farmers wanted skilled male enslaved people. Women were mainly responsible for having and raising children. Family members were often separated when women and children left to find other work. Enslaved people on tobacco farms generally lived longer. Their special skills, learned over many years, were very important to a farmer's success. Tobacco farmers preferred a method called "ganging." Groups of eight to twelve enslaved people worked fields at the same time. They were watched by a white supervisor or an experienced enslaved person. The hardest working enslaved people, called "pace-setters," were placed among the groups to set an example. Unlike tasking, ganging allowed for more supervision and quality control. It also didn't have a clear way to measure how much each person did.

Some experts today say that the Chesapeake was a better place for enslaved people. It was more common in the Chesapeake for an enslaved person to work alongside their master. This was unheard of on the very strict, large farms in the South. White and Black people were more separated in the Deep South. Tasking allowed slave owners to easily replace individuals who didn't meet expectations. Others argue that it's wrong to make one type of slavery seem better than another. They say that neither place was "good" despite these differences.

Colonial Tobacco Culture

How Tobacco Shaped Society

Growing tobacco was seen as a special skill. Unlike cotton or rice, growing tobacco was considered an art. Buyers knew that a good tobacco crop came from a careful farmer with great skills. Tobacco shipments were "branded" with a unique mark from the farmer before being sent overseas. Lenders saw these brands as a sign of approval from the farmer himself. One farmer said about his branded tobacco, "it was made on the plantation where I live and therefore as I saw to the whole management of it my self (sic), I can with authority recommend it to be exceedingly good." Even if they didn't do the manual labor, farmers had a big financial interest in their final product.

Also, a farmer's local reputation and social standing depended on the quality of his tobacco. In his book Tobacco Culture, author T.H. Breen writes "quite literally, the quality of a man’s tobacco often served as the measure of the man." Skilled farmers were highly respected by their peers. They often had a lot of political power in colonial governments. Farmers often spent extra money on expensive luxury goods from London. This showed others that their tobacco was selling well. For example, Thomas Jefferson's Monticello estate was designed like the homes of rich European nobles.

Tobacco and the American Revolution

American tobacco farmers, including Jefferson and George Washington, paid for their farms with large loans from London. When tobacco prices dropped sharply in the 1750s, many farms struggled to stay in business. Serious debt threatened to break apart the colonial power structures. It also risked ruining the farmers' personal reputations. At his Mount Vernon farm, Washington's debts grew to almost £2000 by the late 1760s. Jefferson, who was close to losing his own farm, strongly believed in different conspiracy theories. Though never proven, Jefferson accused London merchants of unfairly lowering tobacco prices. He said they forced Virginia farmers to take on debts they couldn't pay. In 1786, he said:

- "A powerful way for this [merchant profit] was giving good prices and credit to the farmer until they got him deeper in debt than he could pay without selling land or enslaved people. They then lowered the prices for his tobacco so that…they never let him pay off his debt."

Not being able to pay what you owed was seen as more than just a money problem. It was also a moral failing. Farmers whose businesses failed were called "sorry farmers." This meant they couldn't grow good crops and were bad at managing their land, enslaved people, and money. Washington explained his situation like this:

- "Bad luck rather than bad behavior has caused [my debt]…It is an annoying thing for a free mind to always be stuck in debt."

Along with a global money crisis and growing anger toward British rule, tobacco interests helped bring different colonial groups together. They produced some of the strongest voices calling for American independence. A spirit of rebellion grew from their claims that huge debts stopped them from having basic human freedoms.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |