Second Bank of the United States facts for kids

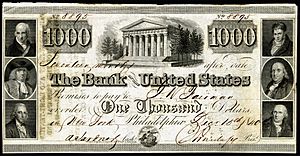

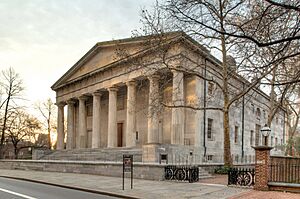

The north façade of the bank on Chestnut Street

|

|

| Public–private partnership | |

| Industry | Banking |

| Fate | Liquidated |

| Founded | 1816 |

| Defunct |

|

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

|

Key people

|

|

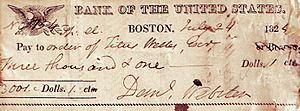

The Second Bank of the United States was a very important national bank in early American history. It was located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and operated from 1816 to 1836. This bank was special because it was allowed to have branches in many states and could lend money to the U.S. government.

It was a mix of a private business and a public service. The bank handled all the money matters for the U.S. government. It also had to answer to Congress and the U.S. Treasury. The federal government owned 20% of the bank, making it the biggest owner. Many private investors, including some from Europe, owned the rest. At the time, it was one of the largest money-handling businesses in the world.

The main job of the bank was to help control the money that private banks created. It also aimed to create a strong and stable national currency for the country. The government's money kept in the bank helped it do this important job.

This bank was inspired by the First Bank of the United States, which was created by Alexander Hamilton. President James Madison approved the Second Bank in 1816. It opened its main office in Philadelphia in January 1817. By 1832, it had 25 branch offices across the country.

The fight to keep the bank open became a big issue in the 1832 United States presidential election. The bank's president, Nicholas Biddle, and his supporters faced off against President Andrew Jackson. Jackson wanted to get rid of the bank, leading to what was called the "Bank War". The bank lost its federal charter in 1836 and became a private company. It eventually closed down in 1841. The U.S. did not have another national bank until the National Bank Act was passed in 1863–1864.

Contents

How the Bank Started

Why a National Bank Was Needed

After the War of 1812, the U.S. government faced many money problems. There was no clear system for currency, and the government's finances were messy. Businesses wanted a safe place for their government bonds. Many people agreed that a national bank was needed to fix these issues.

This time was known as the Era of Good Feelings, where people supported national projects. These included a tax on imported goods and better roads. Leaders like John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay strongly supported creating a new national bank. President James Madison signed the bank's charter into law on April 10, 1816.

Not everyone liked the idea of a new national bank. Some politicians, like John Taylor of Caroline, thought it was against the U.S. Constitution. They also worried it would harm farmers and give too much power to the federal government. Private banks also disliked the national bank because it tried to control their money-lending practices. These groups later played a big role in trying to shut down the bank during President Andrew Jackson's time.

How the Bank Worked with Money

The Second Bank was a national bank, but it wasn't like today's central banks. It didn't set the country's money rules or directly control other banks. Its main job was to help keep the economy stable.

The bank started when Europe was recovering from the Napoleonic Wars. It was supposed to stop private banks from printing too much paper money. Too much paper money could lead to a "credit bubble" and a financial crash. At the same time, the bank also wanted to help people get loans. This was good for businesses in the East and farmers in the West and South.

Under its first president, William Jones, the bank didn't do a good job controlling the money from its branches. This led to a lot of land speculation after the War of 1812. When the U.S. economy crashed in the Panic of 1819, the bank was blamed. Its strict money policies made unemployment worse and property values drop. There were also reports of fraud at its Baltimore office.

William Jones resigned in 1819 and Langdon Cheves took over. He continued to limit credit to stop inflation and stabilize the bank. The bank's actions during this crisis showed its weaknesses. Many Americans began to doubt if paper money was good and who the national banking system really helped. This unhappiness helped Andrew Jackson gain support against the bank in the 1830s.

Things improved when Nicholas Biddle became president in 1823. Under his leadership, the bank became a strong institution. It created a reliable system for national credit and currency. From 1823 to 1833, Biddle carefully expanded credit, which helped the growing American economy.

The Bank War with Andrew Jackson

Jackson's Fight Against the Bank

By the time Andrew Jackson became president in 1829, the bank seemed to be doing well. The Supreme Court had already said it was constitutional. The Treasury Department found it useful, and the country's money was stable. Most people had a good opinion of the bank.

However, Jackson's government attacked the bank in late 1829. They claimed it didn't create stable money and wasn't allowed by the Constitution. Congress investigated and disagreed with Jackson, saying the bank was constitutional and important for currency. Jackson ignored these findings. He privately believed the bank was corrupt and a danger to American freedom.

Biddle tried to reach a compromise with Jackson to renew the bank's charter, which was set to expire in 1836. But he failed. Jackson and his anti-bank supporters continued to criticize the bank. This led to a push by pro-bank politicians, like Henry Clay, to renew the charter early. This fight, known as the Bank War, became a central issue in the 1832 United States presidential election.

Jackson vetoed the bill to renew the bank's charter. His veto was upheld, and he easily won reelection based on his anti-bank stance. Jackson then worked to destroy the bank's power. In 1833, he ordered that federal money be moved from the Second Bank to several private banks. This ended the Second Bank's role in regulating the nation's money.

Biddle tried to cause a financial crisis to force the government to save the bank. But by 1834, people turned against Biddle's actions, and the crisis ended. All efforts to renew the bank's charter were given up.

The Bank Becomes a State Bank

In February 1836, the bank became a private company under Pennsylvania law. A shortage of hard money (gold and silver) followed, leading to the Panic of 1837. This economic downturn lasted for about seven years. The bank stopped making payments from October 1839 to January 1841, and then permanently in February 1841. It then went through a long process of closing down, which ended in 1852.

Bank Locations and Leaders

Branches Across the Country

The Second Bank of the United States had many branches. Here are some of the places where they opened:

|

|

|

Presidents of the Bank

- William Jones, 1817–1819

- James Fisher, 1819 (acting)

- Langdon Cheves, 1819–1823

- Nicholas Biddle, 1823–1836 (federal charter)

- Matthew L. Bevan, 1836–1837? (federal bank estate)

- Nicholas Biddle, 1836–1839 (state charter)

- Thomas Dunlap, 1839–1841

- William Drayton, 1841

- James Robertson, 1841–1852

Rules for the Bank

How the Bank Was Structured

The Second Bank was America's national bank, similar to the Bank of England. But it was different because the U.S. government owned 20% of its capital (money). Other national banks at the time were completely private.

The bank had a capital limit of $35 million, with $7.5 million owned by the government. It had to pay the government a "bonus" of $1.5 million for the right to use public funds without interest. The bank had to report to the U.S. Treasury and Congress and could be inspected by the Treasury Department.

As the government's main financial agent, it provided many services. These included holding all U.S. deposits, handling government payments, and processing tax money. Basically, the bank was "the main bank for the federal government, which was its biggest owner and customer."

The bank was run by 25 directors. Five of these directors were chosen by the President of the United States and approved by the Senate. These government-appointed directors could not work for other banks. Two of the bank's presidents, William Jones and Nicholas Biddle, were chosen from these government directors.

The main office was in Philadelphia. The bank was allowed to open branches wherever it thought best, and these branches were free from state taxes.

How the Bank Controlled Money

The main job of the Second Bank was to control the amount of paper money that state or private banks printed. These private banks made a lot of money by printing notes. The national bank helped manage this growth of credit. It made sure that loans were given out carefully, which helped the economy grow in a healthy way.

Here's how the bank helped control inflation: When government collectors received checks and notes from local banks, they deposited them with the Second Bank. The Second Bank then asked the local banks to pay these amounts in gold and silver coins. Since local banks had to pay in gold and silver, it limited how much money they could lend. The more they lent, the more notes and checks they had out, and the more gold and silver they had to pay. Losing gold and silver reduced their ability to lend more money.

This system helped prevent too much speculation and reduced the risk of a national financial crisis. However, private banks didn't like this system. It forced them to keep enough gold and silver to meet their debts to the U.S. Treasury. The number of private banks grew a lot, from 31 in 1801 to 788 in 1837. This meant the Second Bank faced strong opposition from these banks during Andrew Jackson's time.

The Bank's Architecture

|

Second Bank of the United States

|

|

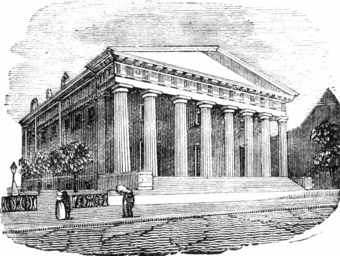

Drawing in an 1875 book

|

|

| Location | 420 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Built | 1818–1824 |

| Architect | William Strickland |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 87001293 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 4, 1987 |

| Designated NHL | May 4, 1987 |

The Building's Design

The architect who designed the Second Bank was William Strickland. He was a student of Benjamin Latrobe, who is often called America's first professional architect. Both Latrobe and Strickland loved the Greek Revival style of architecture. Strickland later designed many other public buildings in this style, including other banks and mints (places where coins are made).

Strickland's design for the Second Bank looks a lot like the Parthenon in Athens, Greece. It's a very important early example of Greek Revival architecture. You can see this style in the north and south sides of the building. They have large steps leading up to a main platform. On this platform, there are eight strong Doric columns. These columns support a triangular roof section called a pediment. The building truly looks like an ancient Greek temple.

The inside of the building has an entrance hallway in the middle of the north side. This hallway is flanked by two rooms on each side. The entrance leads into two large central rooms that stretch across the building from east to west. The building's outside is made of Pennsylvania blue marble. Over time, some parts of the stone have worn away due to weather. This is most noticeable on the columns on the south side. The building was constructed between 1819 and 1824.

The Greek Revival style of the Second Bank is different from the older Federal style used for the First Bank of the United States. The First Bank building is also in Philadelphia and still stands nearby. The First Bank has more Roman-influenced features, like fancy Corinthian columns and decorative windows. It looks more like a Roman villa than a Greek temple.

What the Building Is Used For Today

After the bank closed in 1841, the building was used for many different things. Today, it is part of Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia. You can visit the building for free. It now serves as an art gallery, showing a large collection of portraits of important early Americans. These portraits were painted by artists like Charles Willson Peale. The gallery also features a famous wooden statue of George Washington by William Rush.

The building was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1987 because of its important architecture and history.

The bank's branch office on Wall Street in New York City was turned into the United States Assay Office. It was later torn down in 1915. However, its federal-style front was saved. It was moved and installed in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1924.

See also

In Spanish: Segundo Banco de los Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Segundo Banco de los Estados Unidos para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |